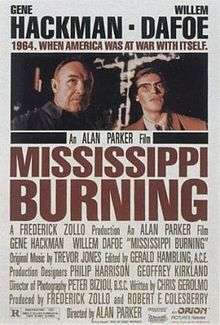

Mississippi Burning

| Mississippi Burning | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Alan Parker |

| Produced by |

Frederick Zollo Robert F. Colesberry |

| Written by | Chris Gerolmo |

| Starring | |

| Music by | Trevor Jones |

| Cinematography | Peter Biziou |

| Edited by | Gerald Hambling |

| Distributed by | Orion Pictures |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 128 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $15 million |

| Box office | $34.6 million[1] |

Mississippi Burning is a 1988 American crime thriller film directed by Alan Parker, and written by Chris Gerolmo. It is loosely based on the FBI's investigation into the murders of three civil rights workers in the state of Mississippi in 1964. Set in the fictional small town of Jessup County, Mississippi, the film stars Gene Hackman and Willem Dafoe as two FBI agents assigned to investigate the disappearance of three civil rights workers. The investigation is met with hostility and backlash by the town's residents, local police and the Ku Klux Klan.

Gerolmo began work on the original script in 1985, inspired by an article and several books detailing the FBI's investigation into the 1964 murders of civil rights workers Andrew Goodman, James Chaney and Michael Schwerner. He and producer Frederick Zollo brought the script to Orion Pictures, and the studio hired Parker to direct the film. Parker and Gerolmo however had disagreements over the script, which resulted in Orion allowing the director to make uncredited rewrites. On a budget of $15 million, the film's principal photography commenced in March 1988 and concluded in May of that year; filming locations included a number of locales in Mississippi and Alabama.

Mississippi Burning held its world premiere at the Uptown Theatre in Washington, D.C. on December 2, 1988. Orion Pictures released Mississippi Burning using a "platform" technique, which involved releasing the film in select cities to generate strong word-of-mouth interest, before expanding distribution in the following weeks. Upon release, the film became embroiled in controversy; it was heavily criticized for its fictionalization of history by black activists involved in the Civil Rights Movement (1954–68) and the families of Goodman, Chaney and Schwerner. Critical reaction towards the film was mixed, though the performances of Hackman, Dafoe and Frances McDormand were generally praised. Mississippi Burning was a modest box office success, grossing $34.6 million during its domestic theatrical run. The film received various awards and nominations; it received seven Academy Award nominations at the 61st Academy Awards in 1989, including Best Picture, Best Director, Best Actor and Best Supporting Actress, but won only one award for Best Cinematography.

Plot

In 1964, three civil rights workers (two Jewish and one black) who organize a voter registry for minorities in Jessup County, Mississippi go missing. The Federal Bureau of Investigation sends two agents, Rupert Anderson—a former Mississippi sheriff—and Alan Ward, to investigate. The pair find it difficult to conduct interviews with the local townspeople, as Sheriff Ray Stuckey and his deputies exert influence over the public and are linked to a branch of the Ku Klux Klan. The wife of Deputy Sheriff Clinton Pell reveals to Anderson in a discreet conversation that the three missing men have been murdered. Their bodies are later found buried in an earthen dam. Stuckey deduces Mrs Pell's confession to the FBI and informs Pell, who brutally beats his wife in retribution.

Anderson and Ward devise a plan to indict members of the Klan for the murders. They arrange a kidnapping of Mayor Tilman, taking him to a remote shack. There, he is left with a black man, who threatens to castrate him unless he talks. The abductor is an FBI operative assigned to intimidate Tilman, who gives him a full description of the killings, including the names of those involved. Although his statement is not admissible in court due to coercion, his information proves valuable to the investigators.

Anderson and Ward exploit the new information to concoct a plan, luring identified KKK collaborators to a bogus meeting. The Klan members soon realize it is a set-up and leave without discussing the murders. The FBI then concentrate on Lester Cowens, a Klansman of interest, who exhibits a nervous demeanor which the agents believe might yield a confession. The FBI pick him up and interrogate him. Later, Cowens is at home when his window is shattered by a shotgun blast. After seeing a burning cross on his lawn, Cowens tries to flee in his truck, but is caught by several hooded men who intend to hang him. The FBI arrive to rescue him, having staged the whole scenario; the hooded men are revealed to be other agents.

Cowens, believing that his fellow Klansmen have threatened his life because of his admissions to the FBI, incriminates his accomplices. The Klansmen are charged with civil rights violations, as this can be prosecuted at the federal level. Most of the perpetrators are found guilty and receive sentences ranging from three to ten years in prison. Stuckey however is acquitted of all charges, and Tilman is later found dead by the FBI in an apparent suicide. Mrs. Pell returns to her home, which has been completely ransacked by vandals, and resolves to stay and rebuild her life, free of her husband. Before leaving town, Anderson and Ward visit an integrated congregation gathered at an African-American cemetery, where the black civil rights activist's desecrated gravestone reads, "Not Forgotten".

Cast

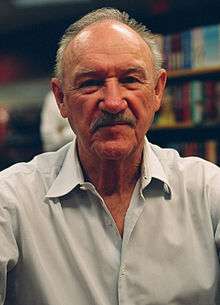

- Gene Hackman as Agent Rupert Anderson

- Willem Dafoe as Agent Alan Ward

- Frances McDormand as Mrs. Pell

- Brad Dourif as Deputy Sheriff Clinton Pell

- R. Lee Ermey as Mayor Tilman

- Gailard Sartain as Sheriff Ray Stuckey

- Stephen Tobolowsky as Clayton Townley

- Michael Rooker as Frank Bailey

- Pruitt Taylor Vince as Lester Cowens

- Badja Djola as Agent Monk

- Kevin Dunn as Agent Bird

- Frankie Faison as Eulogist

- Geoffrey Nauffts as Goatee

- Rick Zieff as Passenger

- Christopher White as Black passenger

- Park Overall as Connie

- Darius McCrary as Aaron Williams

- Robert F. Colesberry as Cameraman

- Frederick Zollo as Reporter

- Tobin Bell as Agent Stokes

- Bob Glaudini as Agent Nash

Historical context

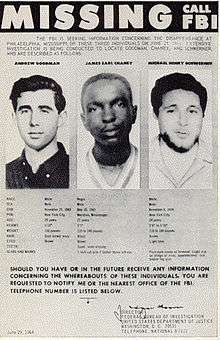

On June 21, 1964, civil rights workers Andrew Goodman, Michael Schwerner and James Chaney were arrested in Philadelphia, Mississippi by Deputy Sheriff Cecil Price, and taken to a Neshoba County jail.[2] The three men had been working on the "Freedom Summer" campaign, attempting to prepare and register African Americans to vote.[3] Price charged Chaney with speeding and held the other two men for questioning.[2] Price released the three men on bail seven hours later and followed them out of town.[4][5] After Goodman, Chaney and Schwerner failed to return to Meridian, Mississippi on time, workers for the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) placed calls to the Neshoba County jail, asking if the police had any information on their whereabouts.[6] Two days later, FBI agent John Proctor and a team of ten FBI agents began their investigation in Neshoba Country. The FBI received a tip about a burning station wagon seen in the woods off of Highway 21, about 13 miles northeast of Philadelphia; the vehicle was a CORE station wagon that had belonged to the missing men. The case became known as "MIBURN"—short for "Mississippi Burning"—[7][8] and top FBI inspectors were sent to help with the investigation.[2]

On August 4, 1964, the bodies of the three men were found after an informant—nicknamed "Mr. X" in FBI reports—passed along a tip to federal authorities.[5][9] They were discovered underneath an earthen dam on a 253-acre farm located a few miles outside Philadelphia, Mississippi.[10] All three men had been shot and killed.[4] Nineteen men were indicted by the U.S. Justice Department for violating the civil rights of Schwerner, Goodman and Chaney.[5] On October 27, 1967, a federal trial conducted in Meridian resulted in seven of the nineteen defendants, including Price, being convicted with sentences ranging from three to ten years; nine were acquitted, and the jury deadlocked on three others.[4]

In 2002, Jerry Mitchell, an investigative reporter for The Clarion-Ledger, discovered new evidence regarding the murders. He also located new witnesses and pressured the state of Mississippi to reopen the case.[11] Adlai E. Stevenson High School teacher Barry Bradford and three of his students aided Mitchell in his investigation after the three students decided to research the "Mississippi Burning" case for a history project.[12]

The identity of Mr. X. was a closely held secret for forty years.[13] In the process of reopening the case, Mitchell, Bradford and the three students discovered the identity of Mr. X; the informant was revealed to be Maynard King, a highway patrolman who revealed the location of the civil rights workers' bodies to FBI Agent Joseph Sullivan.[14] In 2005, one perpetrator, Edgar Ray Killen, was charged for his part in the crimes. He was convicted of three counts of manslaughter, and is currently serving a sixty-year sentence.[5][15]

Production

Development

In 1985, screenwriter Chris Gerolmo discovered an article that excerpted a chapter from the book Inside Hoover's F.B.I., which chronicled the FBI's investigation into the murders of Goodman, Chaney and Schwerner.[16] Gerolmo stated, "In [the book] they made it clear that under intense pressure from Washington, they had gone to considerable extra-legal lengths to solve the case. They had shot up taverns where Klansmen were known to gather. They had beaten people up. They had intimidated and threatened and bribed others. The hair on the back of my neck stood up ... I immediately read the one decent book that had been written at that time about the case, Attack On Terror; The FBI Against the Ku Klux Klan In Mississippi, and my enthusiasm for the idea only grew."[16]

"I never understood this to be Hollywood's 'civil rights' picture. It's an exciting story about something important. You see our moral failures and greatness. It allows us to see America at its very worst and also to see people who displayed great moral courage."

—Chris Gerolmo, screenwriter[17]

As he wrote a draft script, Gerolmo brought it to Frederick Zollo, who had produced Gerolmo's first screenplay, Miles from Home (1988).[18] Zollo helped Gerolmo develop the original draft before they sold it to Orion Pictures.[19] The studio then began its search for a director to helm the project. Filmmakers Miloš Forman and John Schlesinger were among those considered for to helm the project.[18] In September 1987, Alan Parker was given a copy of Gerolmo's script by Orion's executive vice president and co-founder, Mike Medavoy.[19] Parker said, "The power of the opening murder scene and the possibilities that the subsequent story offered drew me to it immediately. It's rare that projects developed in the Hollywood system have any potential for social or political comment and the dramatic possibilities surrounding the two FBI agents had possibly allowed this one to slip through."[19] When Parker traveled to Tokyo, Japan to act as a juror for the 1987 Tokyo International Film Festival, his colleague Robert F. Colesberry began researching the time period, and compiled books, newspaper articles, live news footage and photographs related to the 1964 murders.[20][21] Upon returning to the United States, Parker met with Colesberry in New York and spent several months viewing the research.[19][21] The director also began selecting the creative team; the production of Mississippi Burning reunited Parker with many of his past collaborators, including Colesberry, casting directors Howard Feuer and Juliet Taylor, director of photography Peter Biziou, editor Gerry Hambling, costume designer Aude Bronson-Howard, production designer Geoffrey Kirkland, camera operator Michael Roberts, and music composer Trevor Jones.[19][22]

Writing

Gerolmo described his original draft script as "a big, passionate, violent detective story set against the greatest sea-change in American life in the 20th century, the civil rights movement".[16] For legal reasons, the names of the people and certain details related to the FBI's investigation were changed.[7] On presenting Clinton Pell's wife as an informant, Gerolmo said, "... the fact that no one knew who Mr. X, the informant, was, left that as a dramatic possibility for me, in my Hollywood movie version of the story. That's why Mr. X became the wife of one of the conspirators."[7] The abductor of Mayor Tilman was originally written as a Mafia hitman who forces a confession by putting a pistol in Tillman's mouth. Gerolmo was inspired by Gregory Scarpa, a mob enforcer recruited by the FBI during their search for Goodman, Chaney and Schwerner.[23] Gerolmo said, "In the original screenplay, I wrote the story as I heard it, that there was a Mafioso who owed the FBI a favor who was persuaded to come up and hold a gun in a conspirator's mouth until he told them what they needed to know."[7]

"Our film cannot be the definitive film of the black civil rights struggle, our heroes were still white and, in truth, the film would probably have never been made if they weren't. This is, perhaps, as much a sad reflection on present day society as it is on the film industry. But with all its possible flaws and shortcomings, I hope that our film can provoke thought and kindle the debate allowing other films to be made, because the struggle against racism continues."

—Alan Parker, director[19]

After Parker was hired to direct the film, Gerolmo had completed two drafts.[19] Parker met with Gerolmo at Orion's offices in Century City, Los Angeles, where they began work on a third draft script. Both the writer and director however had repeated disagreements over the focus of the story. Regarding Gerolmo's original draft, Parker said, "The racial events of the period were just too important for the script to read just as a detective story."[18] Gerolmo stated, "After [Parker] was hired it quickly became apparent that he was intent on redoing the script. We did try working together, but he really browbeat me into making all of his changes ... By the end of the first day, he was holding the script up in the air and saying, 'This ain't worth making' ... He took out any lyricism I had in the story and painted all the white people to be ugly, oafish, stupid and drunk."[18]

To resolve the issue, Orion executives in New York gave Parker one month to rewrite the script. The studio would only green-light the project based on the strength of his script.[19] Parker reflected, "The agreement was that, however much I rewrote, I would not take Gerolmo's writing credit and if Orion didn't like my new script, it would be me who would be looking for another job."[19] Gerolmo criticized Orion's decision, stating, "[Parker] is a $1.6 million player in Hollywood and Orion needed an A director who could get the movie ready by Christmas. It's a matter of power."[18]

Parker made several changes from Gerolmo's original draft. He omitted the Mafia hitman and created the character Agent Monk, a black FBI specialist who kidnaps Tilman. He described the character as being "almost a metaphor for what was happening in real life, the assertion of black anger, and black rights reasserting themselves."[7] The scene in which Frank Bailey brutally beats a news cameraman was based on an actual event; Parker and Colesberry were inspired by a news outtake found during their research, in which a CBS News cameraman was assaulted by a suspect in the 1964 murder case.[18] Parker also wrote a sex scene involving Rupert Anderson and Mrs. Pell. The scene was omitted during filming after Gene Hackman, who portrays Anderson, suggested to Parker that the relationship between the two characters be more discreet.[18] Hackman said, "Originally, [Parker] wanted [Anderson] to make love to [Mrs. Pell] right then, on the floor of her house. I felt that was excessive and would distract from her as a human being and from her courage in terms of what has just revealed ... We finally agreed that the lovemaking would be left out ... I felt [Anderson] did care for her a lot, and in the end made a decision to just let her be, not to complicate her life further."[24]

By January 4, 1988, Parker had written a complete shooting script, which he submitted to Orion executives. "My screenplay was fortunately liked by everyone (if not Gerolmo) and it was agreed by the Orion hierarchy for us to press on," he said.[19] Gerolmo was not involved in the film's production, due to a 1988 Writers Guild of America strike that would coincide with the film's principal photography.[20] He has since voiced his support of the finished film, stating, "I think largely the structure remains the same. Almost every scene is the same, but what directors change, and have the prerogative to change, is the dialogue. [Parker] wanted to add to the screenplay that this was a film about the issues, so he put in more material and more discussion and more dialogue about civil rights."[21]

Casting

The filmmakers did not retain the names of actual people; many of the characters were composites of people from the era.[7] Gene Hackman plays Rupert Anderson, an FBI agent and former Mississippi sheriff.[20] Brian Dennehy was briefly considered for the role[25] before Orion suggested Hackman.[20] During the screenwriting process, Parker discussed the project with Hackman. The director stated, "... although keen on the subject matter, [Hackman] was not overly impressed with [Gerolmo's] script — and so was interested to know where our new script would take us."[19] Hackman said, "... it felt right to do something of historical import. It was an extremely intense experience, both the content of the film and the making of it in Mississippi."[24] On preparing for the role, Hackman said, "I read everything I could get my hands on about that period and the incident, including the book Three Lives for Mississippi. In a curious way, I got a lot of insight from a book called [The Courting of Marcus Dupree], which paralleled the life of a black football player born on or near the day of the murders. It was done in such a way as to imply that the civil rights workers' deaths were not in vain: They died so that he could live."[24]

Orion was less resolute in terms of who they wanted for the role of Agent Alan Ward. After filming The Last Temptation of Christ (1988), Willem Dafoe expressed interest in playing Ward,[20] and Parker traveled to Los Angeles, where he met with the actor to discuss the role. Dafoe was cast shortly thereafter.[19] Regarding the character of Ward, Dafoe stated, "In this film, the dilemma is - where does this FBI guy's moral stance harden into a posture of blind arrogance? That's fascinating to me. You have this guy – [Ward] – who's so morally correct, but fatally compromised by the crusader mentality."[18] To prepare for the role, Dafoe researched the time period and Neshoba County. He also read Willie Morris's 1983 novel The Courting of Marcus Dupree, and looked at 1960s documentary footage detaling how the media covered the murder case.[26]

Parker described the casting of supporting actors as a lengthy process. He held casting calls in New York, Atlanta, Houston, Dallas, Orlando, New Orleans, Raleigh and Nashville.[19] Frances McDormand plays Mrs. Pell, the wife of Deputy Sheriff Clinton Pell. On working with Hackman, McDormand said, "... in Mississippi Burning, I didn't do research. All I did was listen to [Hackman]. He had an amazing capacity for not giving away any part of himself (in read-throughs). But the minute we got on the set, little blinds on his eyes flipped up and everything was available. It was mesmerizing. He's really believable, and it was like a basic acting lesson."[27]

Gailard Sartain plays Ray Stuckey, the sheriff of Jessup County—a composite of former Neshoba County sheriff Lawrence A. Rainey.[20][28] Sartain described Stuckey as "an elected official ... who has to be gregarious - but with sinister overtones". He continued, "... that's how Alan Parker wanted me to play it. He called it 'bonhomie'. Told me to keep the bonhomie in it. It's not a character I've played 100 times. It's totally different.".[29] Stephen Tobolowsky plays Clayton Townley, a Grand Wizard of the White Knights of the Ku Klux Klan.[20] The character is a composite of White Knights leader Samuel Bowers.[30] Tobolowsky said, "[Parker] asked me how I saw the man, and I said, 'I saw him as Abraham Lincoln — I don't see him as a villain. This man is a hero with his agenda, with his point of view.' I did not intend to play Clayton Townley as one chromosome short of a human being, like a lot of people will play various villains in movies ... In real life, everyone kind of sees themselves as the good guy, doing what they're doing. They see themselves as a kind of hero, and I wanted to make sure Clayton Townley ... wasn't played as some kind of genetic miscreant."[31]

Michael Rooker plays Frank Bailey, a Klansman involved in the murders of the three civil rights activists. Rooker described Bailey as a "very evil and tough character", and noted the seriousness of the film's production: "Mississippi Burning was one of those movies where there was not a lot of joking (on the set). It was a pretty heavy, heavy piece."[32] Pruitt Taylor Vince, who had a small role in Parker's previous film Angel Heart, plays Lester Cowens, a Klansman who unknowingly becomes a pawn in the FBI's investigation. Vince described the character as "goofy, stupid and geeky" and stated, "I never had a prejudiced bone in my body. It gave me a funny feeling to play this guy with a hood and everything. But when you're in the midst of it, you just concentrate on getting through it."[33]

Kevin Dunn joined the production in February 1988, appearing in his acting debut as FBI Agent Bird.[34] Tobin Bell, also making his feature film debut, plays Agent Stokes,[35] an FBI enforcer hired by Anderson to interrogate Cowens.[20] Bell was first asked by Parker to read for the role of Clinton Pell, a role that was ultimately given to Brad Dourif. On securing a role in the film, Bell said, "Alan Parker saw my headshot ... He brought me in. He doesn't even have a casting director in the room. He sets up a video camera and he talks to you. It was slightly embarrassing, because Alan would say to me, 'Tobin, don't act.' He was looking for somebody who, under pressure, could do something minimal. The camera sees everything. He had me do this a number of times, and disappeared to Los Angeles, cast the rest of the film, came back to New York, and brought me in again. Then same thing, except he read me for a different part."[36]

Appearing as the three civil rights activists are Geoffrey Nauffts as "Goatee", a character based on Michael Schwerner; Rick Zieff as "Passenger", based on Andrew Goodman; and Christopher White as "Black Passenger", based on James Chaney.[20][22] Producers Frederick Zollo and Robert F. Colesberry also make appearances in the film; Zollo briefly appears as a news reporter,[22] and Colesberry appears as a news cameraman who is brutally beaten by Frank Bailey.[19]

While scouting locations in Jackson, Mississippi, Parker arranged an open casting call for local actors and extras. The director reflected, "... we had arranged an 'open call' advertising on the radio and in local newspapers for anyone, who wanted to be in a movie. Nearly two thousand turned up and were dutifully photographed and ushered through the filtering process allowing me to read with as many people as possible."[19] Parker and Colesberry met music teacher Lannie McBride, who appears as a gospel singer in the film. Parker said, "[McBride] was advising us on the gospel music used in the film. We spent many hours at Lanny's church as her choir ran through many options she had suggested."[19]

Filming

Location scouting

During the screenwriting process, Parker and Colesberry began scouting locations; they looked at over 300 small towns in eight states, based on suggestions made by the location department. The shooting script required that a total of 62 locations be used for filming.[19] In December 1987, Parker and Colesberry traveled to Mississippi to visit the stretch of road where Goodman, Chaney and Schwerner were murdered.[20] The filmmakers were initially reluctant about filming in Mississippi. John Horne, head of the state's film commission, said, "When I first spoke to them, I heard a lot of hesitancy. They'd been doing research in other parts of the South, but I was told they were scared to come to Mississippi. They were even scouting locations in Forsyth County, Georgia (a renowned hotbed of Ku Klux Klan activity). So I said, 'Hey, if you can shoot this movie in Forsyth County, you can shoot it here!'"[18] Parker also met with Mississippi governor Ray Mabus, who voiced his support of the film's production. He said, "[Mabus] was extremely gracious and encouraging, his concern being 'the new Mississippi' — firm in the belief that if Mississippi had a chance at a future, it had to own up to its past."[19]

Parker and Colesberry looked at locations near Jackson, Mississippi, where they set up production offices at a Holiday Inn hotel.[19] They also looked at locations in Canton, Mississippi before travelling to Vaiden, Mississippi, where they scouted more than 200 courthouses that could be used for filming.[19] Parker and Colesberry had difficulty finding a small town for the story setting. "Colesberry had decided that if we couldn't settle on our small town at this point he should base our operation out of Jackson, as I was determined to be in Mississippi," Parker said, "and he was confident that the major part of our filming could be effectively done from a striking distance from the city."[19] Parker and Colesberry also had difficulty finding abandoned churches that could be burned down for several scenes. It was ultimately decided that LaFayette, Alabama would act as scenes set in the fictional town of Jessup County, Mississippi, with other scenes being shot in a number of locales in Mississippi.[19]

Principal photography

Principal photography began on March 7, 1988[19] on a budget of $15 million.[18][21][37] Filming began in Jackson, Mississippi, where the production team filmed a church being burned down. The sequence required a multiple-camera setup; a total of three cameras were used during the shoot. The crew however expressed concerns as the cameras were placed too close to the flames. This resulted in the sequence being filmed in two takes.[19] On March 8, the production team filmed a scene set in a motel where Anderson (Hackman) delivers a monologue to Ward (Dafoe).[19] On March 10, production moved to a remote corner of Mississippi, where the crew filmed the burning of a parish church. The art department created a small cemetery at the front of the church before the church itself was burned down. Parker said of the location, "The church had become derelict many years ago, when the fields had ceased to be worked and the locals had been forced to move away from this remote corner of Mississippi. At the height of the fire the heat began to suck the moisture from the ground, enveloping the old church and cemetery in an eery mist, and it was hard to imagine that 'prop' graves weren't real."[19]

On March 11, the production filmed scenes set in a pig farm, where a young boy is confronted and attacked by three perpetrators. A night later, the crew shot the film's opening sequence, in which the three civil rights workers are murdered.[19] From March 14 to March 18, the crew filmed the burning of several more churches, as well as scenes set in a farm.[19] On March 22, the crew filmed scenes set in a morgue that was located inside the University of Mississippi Medical Center, exactly the same location where the bodies of Goodman, Chaney and Schwerner were transported.[19] A day later, Parker and the crew filmed a scene set in a cotton field. The art department had to dress each plant with layers of cotton, as the cotton plants had not fully bloomed. "It wasn't the ideal time of year to show the cotton in full bloom and the cotton was 'dressed', plant by plant, by the entire crew who volunteered to help out the pressed art department to undertake the mammoth task," Parker said.[19] The crew also filmed the abduction of Mayor Tilman (R. Lee Ermey) and his subsequent interrogation by FBI agent Monk (Badja Djola).[19]

On March 24, the production moved to Raymond, Mississippi, where the crew filmed a scene at the John Bell Williams Airport.[19] Depicting Monk's departure, the scene was choreographed by Parker and the cast members so that it could be shot in one take. Parker said of the scene, "We had choreographed everything so that the whole scene could be shot in one take, allowing [Hackman and Dafoe] to build up a head of steam with their performances ... I wrote the scene because I felt that an important and dangerous shift in morality had taken place in our story which had to be addressed and articulated as Ward abandons his principled approach acquiescing to Anderson's street pragmatism."[19]

The production then moved to Vaiden, Mississippi to film scenes set in the Carroll County Courthouse, where several courtroom scenes, as well as scenes set in Sheriff Ray Stuckey's office were filmed.[19][20] The production moved to Vicksburg, Mississippi, where the crew filmed a funeral procession. On April 11, 1988, the crew filmed a scene set in the Cedar Hill Cemetery.[19] From April 15 to April 16, the production moved to the Mississippi River valley to depict the FBI and United States Navy's search for the three civil rights workers. The art department recreated a Choctaw Indian Village on the location, based on old photographs.[19] On April 23, the crew filmed a Citizens' Councils rally. "Ironically, for a director, large crowd scenes are often easier to shoot than two people in a room," Parker said. "But for everyone else on the crew it was a nightmare: seven hundred and fifty extras in period costume, two hundred period cars, ten buses, thirty trucks, a hundred crew and police, and, fittingly, three borrowed circus tents in which to feed everyone."[19] On April 25, the crew returned to Jackson, Mississippi, where an unused building was to recreate a diner that was found in Alabama during location scouting. A day later, Hackman and Dafoe filmed their opening scene, in which the characters Anderson and Ward drive to Jessup County, Mississippi.[19]

On April 27, the production moved to LaFayette, Alabama for the remainder of filming.[19] From April 28 to April 29, Parker and his crew filmed scenes set in Mrs. Pell's home. On May 5, the production shot one of the film's final scenes, in which Anderson discovers Mrs. Pell's home trashed. Parker described the scene as "an ugly scene and not pleasurable to shoot". On May 13, the crew filmed scenes in a former LaFayette movie theatre, which had now become a store for tractor tires. The art department restored the theatre's interiors to reflect the time period.[19] Filming concluded on May 14, 1988 after the production filmed a Ku Klux Klan speech that is overseen by the FBI.[19]

Music

The film score for Mississippi Burning was produced, arranged and composed by Trevor Jones; the film marked his second collaboration with Parker after Angel Heart.[38] Regarding the score, Jones said, "The thing about Mississippi Burning was that the underscore had one very essential rhythmic idea which I came up with early on ... and what I said to [Parker] was what if we use that idea throughout the film to psychologically signal to the audience there's danger near?"[38] Jones described the score as "a very complicated score (given the historical circumstances it described) but based on a very simple motif—a motif that was constructed from 20 different ways of playing it".[38] In addition to Jones's score, the soundtrack features several gospel songs, including "Walk on by Faith" performed by Lannie McBride, "Take My Hand, Precious Lord" performed by Mahalia Jackson and "Try Jesus" performed by Vesta Williams. A motion picture soundtrack album was released by the recording labels Antilles Records and Island Records.[39]

Release

%2C_London%2C_2012.jpg)

Mississippi Burning held its world premiere at the Uptown Theatre in Washington, D.C. on December 2, 1988.[40] In addition to the cast and crew, the premiere was attended by various politicians, ambassadors and political reporters. At the premiere, United States Senator Ted Kennedy voiced his support of the film, stating, "This movie will educate millions of Americans too young to recall the sad events of that summer about what life was like in this country before the enactment of the civil rights laws."[40]

Mississippi Burning was given a "platform release", first being released in a small number of cities in North America before opening wide across the United States and Canada; the film opened in Washington, Los Angeles, Chicago, Toronto and New York City on December 9, 1988.[40][41] The film's distributor, Orion Pictures, was confident that the limited release would qualify the film for Academy Awards consideration, and generate strong word-of-mouth support from audiences.[40][42] Mississippi Burning was released across North America on January 27, 1989,[43] playing at 1,058 theaters, and expanding to 1,074 theatres by its ninth week.[44]

Box office

Mississippi Burning's first week of limited release saw it take $225,034—an average of $25,003 per theater.[44] The film grossed an additional $160,628 in its second weekend.[44] More theaters were added during the limited run, and on January 27, 1989, the film officially entered wide release. By the end of its opening weekend of wide release, the film had grossed $3,545,305, securing the number five position at the domestic box office with an overall domestic gross of $14,726,112.[44] The film generated strong local interest in the state of Mississippi, resulting in sold-out showings in the first four days of wide release.[45] After seven weeks of wide release, Mississippi Burning ended its theatrical run with an overall gross of $34,603,943.[44] In North America, it was the thirty-third highest-grossing film of 1988[46] and the seventeenth highest-grossing R-rated film of that year.[47]

Home media

Mississippi Burning was released on VHS on July 27, 1989 by Orion Home Video.[48] A "Collector's Edition" of the film was released on LaserDisc on April 3, 1998.[49] The film was released on DVD on May 8, 2001 by MGM Home Entertainment. Special features for the DVD include an audio commentary by Parker and a theatrical trailer.[50] The film was released on Blu-ray disc on May 12, 2015 by the home video label Twilight Time, with a limited release of 3,000 copies. The Blu-ray presents the film in 1080p high definition, and contains the additional materials found on the MGM Home Entertainment DVD.[51]

Reception

Critical response

.jpg)

The review aggregation website Rotten Tomatoes sampled 18 reviews, and gave Mississippi Burning a score of 89%, with an average score of 6.4 out of 10.[52] Another review aggregator, Metacritic, assigned the film a weighted average score of 65 out of 100 based on 11 reviews from mainstream critics, indicating "generally favorable reviews".[53]

The film received a mixed reaction from critics upon release. In a review for Time magazine entitled "Just Another Mississippi Whitewash", author Jack E. White described the film as a "cinematic lynching of the truth". He wrote, "It is bad enough that most Americans know next to nothing about the true story of the civil rights movement. It would be even worse for them to embrace the fabrications in Mississippi Burning."[54] Columnist Desson Howe of The Washington Post believed that the film "speeds down the complicated, painful path of civil rights in search of a good thriller. Surprisingly, it finds it". He felt the film was a "Hollywood-movie triumph that blacks could have used more of during – and since – that era."[55] Jonathan Rosenbaum of the Chicago Reader, lightly criticized Parker's direction, commenting that the film was "sordid fantasy" being "trained on the murder of three civil rights workers in Mississippi in 1964, and the feast for the self-righteous that emerges has little to do with history, sociology, or even common sense."[56] Rita Kempley of The Washington Post wrote, "... like the South African saga Cry Freedom, it views the black struggle from an all-white perspective. And there's something of the demon itself in that. It's the right story, but with the wrong heroes."[57] Pauline Kael, writing for The New Yorker, praised the acting, but criticized the film's "garish forms of violence" and described it as "morally repugnant".[58]

Vincent Canby of The New York Times praised the film's fictionalization of history, writing in his review, "It is relentless in the way it maintains its focus. Virtually every image says that this is the way things were, and may still be. Think about it. The film doesn't pretend to be about the civil-rights workers themselves. It's almost as if Mr. Parker and Mr. Gerolmo respected the victims, their ideals and their fate too much to reinvent them through the use of fiction."[59] In his review for the Chicago Sun-Times, Roger Ebert surmised, "We knew the outcome of this case when we walked into the theater. What we may have forgotten, or never known, is exactly what kinds of currents were in the air in 1964."[60] On the syndicated television program Siskel and Ebert and the Movies, Ebert and his colleague Gene Siskel gave the film a "two thumbs up" rating.[61] Siskel, writing for the Chicago Tribune, praised Hackman and Dafoe's "subtle" performances but felt that McDormand was "most effective as the film's moral conscience".[62]

Variety magazine praised the performances, writing, "Dafoe gives a disciplined and noteworthy portrayal of Ward ... But it's Hackman who steals the picture as Anderson ... Glowing performance of Frances McDormand as the deputy's wife who's drawn to Hackman is an asset both to his role and the picture."[63] Sheila Benson, in her review for the Los Angeles Times, wrote, "Part of the film's pull comes from the delicacy of the playing between Hackman and McDormand. Hackman's mastery at suggesting an infinite number of layers beneath a wry, self-deprecating surface reaches a peak here, but McDormand soars right with him. And since she is the film's sole voice of morality, it's right that she is so memorable."[64]

Controversy

"... with Mississippi Burning the controversy got out of hand. It was impossible to turn on a TV without someone discussing the movie — or using the movie to trigger the debate. Often it was black politicians and activists attacking my film but mostly one another because there certainly was no consensus in the black community towards the film. For myself I was somewhat bemused by it all — and a little punch-drunk. In the beginning it was rather nice to have your film talked about but suddenly the tide turned and although it did well at the box office, we were dogged by a lot of anger that the film generated."

—Parker reflecting on the film's controversy.[19]

Following its release, Mississippi Burning became embroiled in controversy over its fictionalization of events; it was heavily criticized by black activists who were involved in the Civil Rights Movement (1954–68), as well as the families of Goodman, Chaney and Schwerner. Coretta Scott King, widow of Martin Luther King, Jr., boycotted the film, stating, "How long will we have to wait before Hollywood finds the courage and the integrity to tell the stories of some of the many thousands of black men, women and children who put their lives on the line for equality?"[65] Myrlie Evers-Williams, the wife of slain civil rights activist Medgar Evers, said of the film, "It was unfortunate that it was so narrow in scope that it did not show one black role model that today's youth who look at the movie could remember."[17] Benjamin Hooks, the executive director of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), stated that the film, in its fictionalization of historical events, "reeks with dishonesty, deception and fraud" and portrays African Americans as "cowed, submissive and blank-faced".[66]

Carolyn Goodman, mother of Andrew Goodman, and Ben Chaney, Jr., the younger brother of James Chaney, expressed that they were both "disturbed" by the film.[67] Goodman described Mississippi Burning as "a film that used the deaths of the boys as a means of solving the murders and the FBI being heroes."[67] Chaney stated, "... the image that younger people got (from the film) about the times, about Mississippi itself and about the people who participated in the movement being passive, was pretty negative and it didn't reflect the truth."[67] Stephen Schwerner, brother of Michael Schwerner, stated that Mississippi Burning was a "terribly dishonest and very racist" film that "distorts the realities of 1964".[66]

On a Martin Luther King, Jr. Day (January 16, 1989) episode of ABC's late-night news program Nightline, Julian Bond, a social activist and leader in the Civil Rights Movement, nicknamed the film "Rambo Meets the Klan"[68] and criticized its depiction of the FBI: "People are going to have a mistaken idea about that time ... It's just wrong. These guys were tapping our telephones, not looking into the murders of [Goodman, Chaney and Schwerner]."[68] Filmmaker Spike Lee criticized the film for its lack of central black characters; he felt it was among several other films that used a white savior narrative to exploit blacks in favor of depicting whites as heroes. When asked about the film at the 1989 Cannes Film Festival, Lee responded, "Hated it. They should have had the guts to have at least one central black character."[69]

In response to these criticisms, Parker defended the film, stating that it was "fiction in the same way that Platoon and Apocalypse Now are fictions of the Vietnam War. But the important thing is the heart of the truth, the spirit ... I defend the right to change it in order to reach an audience who knows nothing about the realities and certainly don't watch PBS documentaries."[7]

Litigation

On February 21, 1989, former Neshoba County sheriff Lawrence A. Rainey filed a lawsuit against Orion Pictures, claiming defamation and invasion of privacy. The lawsuit, filed at a United States district court in Meridian, Mississippi, asked for $8 million in damages.[28] Rainey, who was the town's sheriff at the time of the 1964 murders, alleged that the filmmakers of Mississippi Burning had portrayed him in an unfavorable light with the fictional character of Sheriff Ray Stuckey (Gailard Sartain). "Everybody all over the South knows the one they have playing the sheriff in that movie is referring to me," he stated. "What they said happened and what they did to me certainly wasn't right and something ought to be done about it."[28] Rainey's lawsuit was unsuccessful; he dropped the suit after Orion's team of lawyers threatened to prove that the film was based on fact, and that Rainey was indeed suspected in the 1964 murders.[70]

Accolades

Mississippi Burning received various awards and nominations in categories ranging from recognition of the film itself to its writing, direction, editing, sound and cinematography, to the performances of Gene Hackman and Frances McDormand. It was named one of the "Top 10 Films of 1988" by the National Board of Review. The organization also awarded the film top honors at the 60th National Board of Review Awards: Best Film, Best Director, Best Actor and Best Supporting Actress.[71]

In January 1989, the film received four Golden Globe Award nominations for Best Motion Picture – Drama, Best Director, Best Screenplay and Best Actor – Motion Picture Drama (Hackman),[72] though it failed to any win of the awards at the 46th Golden Globe Awards.[73] In February 1989, Mississippi Burning was nominated for seven Academy Awards, including Best Picture, Best Director and Best Actor; its closest rivals were Rain Man leading with eight nominations, and Dangerous Liaisons, which also received seven nominations.[74] On March 29, 1989, at the 61st Academy Awards, the film won only one of the seven awards for which it was nominated: Best Cinematography.[75] At the 43rd British Academy Film Awards, the film received five nominations, ultimately winning for Best Sound, Best Cinematography and Best Editing.[76] In 2006, the film was nominated by the American Film Institute for its 100 Years...100 Cheers list.[77]

See also

- 1988 in film

- African-American Civil Rights Movement (1954–68)

- African-American Civil Rights Movement in popular culture

- White savior narrative in film

References

- Footnotes

- ↑ "Mississippi Burning (1988)". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 2014-10-26.

- 1 2 3 "FBI — 50 Years Since Mississippi Burning". FBI.gov. Retrieved May 23, 2016.

- ↑ Smith, Stephen (June 20, 2014). ""Mississippi Burning" murders resonate 50 years later - CBS News". CBS News. Retrieved May 23, 2016.

- 1 2 3 Montado, Charles. "The Murders and Trial - Mississippi Burning Part 2". Retrieved May 23, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 "Slain civil rights workers found - Aug 04, 1964 - HISTORY.com". History Television Channel. Retrieved May 23, 2016.

- ↑ Montado, Charles. "The 'Mississippi Burning' Case - Civil Rights Movement". Retrieved May 23, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 King, Wayne (December 4, 1988). "FILM; Fact vs. Fiction in Mississippi". The New York Times. The New York Times Company. Retrieved April 29, 2016.

- ↑ "FBI — Mississippi Burning (MIBURN) Case". FBI.gov. Retrieved May 8, 2016.

- ↑ Whitehead, Don (September 1970). "Murder in Mississippi". Reader's Digest: 214.

- ↑ Cartha D. Deloach (June 25, 1995). Hoover's F. B. I.: The Inside Story by Hoover's Trusted Lieutenant (First ed.). Regnery Publishing, Inc. ISBN 978-0-89526-479-4.

- ↑ Mitchell, Jerry. "Mississippi Burning". BarryBradford.com. Retrieved May 4, 2016.

- ↑ Gilbert, Kathy L. (March 9, 2005). "Students, teacher 'carry burden' for slain civil rights workers". United Methodist Church. United Methodist News Service. Retrieved May 23, 2016.

- ↑ Mitchell, Jerry. "New details on the FBI paying $30K to solve the Mississippi Burning case". Journey to Justice. The Clarion-Ledger. Retrieved May 4, 2016.

- ↑ Mitchell, Jerry. "Mississippi Burning - Who is Mr. X?". BarryBradford.com. Retrieved May 4, 2016.

- ↑ Parker, Alan. "A Conviction in Mississippi - Alan Parker - Director, Writer, Producer - Official Website". AlanParker.com. AlanParker.com. Retrieved May 23, 2016.

- 1 2 3 Gerolmo, Chris (February 26, 2014). "Mississippi Burning, Reconsidered". Huffington Post. Huffington Post. Retrieved April 29, 2016.

- 1 2 Bob Thomas (March 23, 1989). "Picture Oscar Field Wide-Ranging". The Schenectady Gazette. Schenectady, New York.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Goldstein, Patrick (June 1989). "Classic Feature: Mississippi Burning". Empire. AFI. Retrieved April 29, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 Parker, Alan. "Mississippi Burning - Alan Parker - Director, Writer, Producer - Official Website". AlanParker.com. AlanParker.com. Retrieved April 29, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 David F. Gonthier, Jr.; Timothy L. O'Brien (May 2015). "9. Mississippi Burning, 1988". The Films of Alan Parker, 1976–2003. United States: McFarland & Company. pp. 162–182. ISBN 978-0-7864-9725-6.

- 1 2 3 4 Ressner, Jeffrey (November 17, 1988). "The Burning Truth". Rolling Stone. Vol. 539. United States. pp. 45–46.

- 1 2 3 "Index to Motion Picture Credits - Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Retrieved May 11, 2016.

- ↑ MacAskill, Ewan (October 31, 2007). "FBI used mafia capo to find bodies of Ku Klux Klan victims". The Guardian. Guardian News and Media Ltd. Retrieved April 29, 2016.

- 1 2 3 Terry, Clifford (September 9, 1990). "Brian Interview: Gene Hackman". Film Comment. Film Society of Lincoln Center. Retrieved April 29, 2016.

- ↑ Terry, Clifford (September 9, 1990). "Brian Dennehy's Quest". Chicago Tribune. Chicago Tribune. Retrieved April 29, 2016.

- ↑ Reynolds, Harold (January 17, 1989). "Provocative Dafoe Prefers His Film Roles Served Hot". Orlando Sentinel. Orlando Sentinel. Retrieved May 1, 2016.

- ↑ Dafoe, Willem. "Frances McDormand by Willem Dafoe". BOMB Magazine. Retrieved May 11, 2016.

- 1 2 3 Associated Press (February 23, 1989). "Sheriff sues film studio, claiming he was libeled". Spokane Chronicle. Spokane, Washington.

- ↑ Wooley, John (January 13, 1989). "Tulsa's Gailard Sartain Takes on Serious Role In "Mississippi Burning'". Tulsa World. Retrieved June 2, 2016.

- ↑ Smith, John David; Appleton, Thomas H.; Roland, Charles Pierce (January 1997). "9. Hollywood and the Mythic Land Apart 1988–1990". A Mythic Land Apart: Reassessing Southerners and Their History. United States: Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 179–180. ISBN 978-0-313-29304-7.

- ↑ "Tobolowsky: An Actor's Life 'Low On The Totem Pole'". NPR. NPR. October 3, 2012. Retrieved May 30, 2016.

- ↑ Meszoros, Mark (February 3, 2013). "Michael Rooker talks 'Mississippi Burning,' 'Guardians of the Galaxy'". The Morning Journal. The Morning Journal. Retrieved May 30, 2016.

- ↑ Russell, Candace (February 3, 1989). "Actor Says 'Mississippi' Bad-guy Role Was A Good Part". Sun-Sentinel. Retrieved May 11, 2016.

- ↑ O' Malley, Kathy; Gratteau, Hanke (February 21, 1988). "Bidding Wars ...". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved June 2, 2016.

- ↑ Harrington, Richard (October 26, 2007). "Tobin Bell: A Pivotal Piece of the 'Saw' Puzzle". The Washington Post. The Washington Post Company. Retrieved May 11, 2016.

- ↑ Heisler, Steve (October 29, 2008). "Tobin Bell · Random Roles". The A.V. Club. The Onion, Inc. Retrieved May 11, 2016.

- ↑ Goldstein, Patrick (June 5, 1988). "A Time for Burning--Murder in Mississippi". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved April 29, 2016.

- 1 2 3 Benitez, Sergio. "Two Days with Trevor Jones at the Phone (First Day)". BSO Spirit. Retrieved April 29, 2016.

- ↑ "Trevor Jones - Mississippi Burning (Original Soundtrack Recording) (Vinyl, LP, Album)". Discogs. Retrieved April 29, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 Pagano, Penny. "Civil Rights Star in D.C. Film Opening". Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved April 29, 2016.

- ↑ Wilson, John M. "'Burning' Mad in Ole Miss". Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved April 29, 2016.

- ↑ Brown, Tony (February 25, 1989). "Hollywood dirty little secret". Indianapolis Recorder. Indianapolis, Indiana.

- ↑ "Mississippi Burning (1988)". Box Office Mojo. Internet Movie Database. Retrieved April 29, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Mississippi Burning (1988) - Weekend Box Office Results". Box Office Mojo. Internet Movie Database. Retrieved April 29, 2016.

- ↑ Adam Nossiter (Jun 16, 2009). "8. Downfall of the Old Order and Reawakening of Memory". Of Long Memory: Mississippi and the Murder of Medgar Evers. United States: Da Capo Press. pp. 228–231. ISBN 978-0-306-81162-3.

- ↑ "1988 Yearly Box Office Results". Box Office Mojo. Internet Movie Database. Retrieved April 29, 2016.

- ↑ "1988 Yearly Box Office for R Rated Movies". Box Office Mojo. Internet Movie Database. Retrieved April 29, 2016.

- ↑ Stephens, Mary (July 21, 1989). "Old Stars, New Kids In Summer Rock Tapes". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved April 29, 2016.

- ↑ "Mississippi Burning: Collector's Edition [ID3922OR]". LaserDisc Database. Retrieved April 29, 2016.

- ↑ "Mississippi Burning (1988) - DVD". Barnes & Noble. Retrieved 2014-11-04.

- ↑ "Mississippi Burning Blu-ray". Blu-ray.com. Retrieved 2015-06-09.

- ↑ "Mississippi Burning (1988) - Rotten Tomatoes". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved April 29, 2016.

- ↑ "Mississippi Burning". Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Retrieved April 29, 2016.

- ↑ White, Jack E. (January 9, 1989). "Show Business: Just Another Mississippi Whitewash". Time. White's review is quoted in Roman, James (2009). Bigger Than Blockbusters: Movies That Defined America. ABC-CLIO. p. 274. ISBN 978-0-313-08740-0.

- ↑ Howe, Desson (December 9, 1988). "Mississippi Burning (R)". The Washington Post. The Washington Post. Retrieved 2014-10-26.

- ↑ "Mississippi Burning (R)". Chicago Reader. Retrieved 2014-10-26.

- ↑ "Mississippi Burning (R)". The Washington Post. The Washington Post. Retrieved April 30, 2016.

- ↑ "Kael Reviews". Retrieved April 29, 2016.

- ↑ Canby, Vincent (December 9, 1988). "Review/Film - Retracing Mississippi's Agony, 1964". The New York Times. The New York Times Company. Retrieved April 29, 2016.

- ↑ Ebert, Roger (December 9, 1988). "Mississippi Burning". Chicago Sun-Times. RogerEbert.com. Retrieved April 29, 2016.

- ↑ Gene Siskel and Roger Ebert (December 3, 1988). Siskel and Ebert and the Movies.

- ↑ Siskel, Gene (December 9, 1988). "Subtle Portrayals Imbue Heavy Drama 'Burning'". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved April 29, 2016.

- ↑ Variety Staff (December 31, 1988). "Review: 'Mississippi Burning'". Variety. Variety Media, LLC. Retrieved April 30, 2016.

- ↑ Benson, Sheila (December 18, 1988). "RCritic's Notebook: Some 'Burning' Questions". Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved April 30, 2016.

- ↑ Toplin, Robert Brent (1996). "Mississippi Burning: A Standard to Which We Couldn't". History by Hollywood: The Use and Abuse of the Hollywood Past. United States: University of Illinois Press. pp. 26–27. ISBN 978-0-252-06536-1.

- 1 2 "Brother of Slain Rights Worker Blasts Movie". Associated Press. January 18, 1989. Retrieved July 20, 2016.

- 1 2 3 Leftovsky, Irv. "Another Case of Murder in Mississippi : TV movie on the killing of three civil rights workers in 1964 tries to fill in what 'Mississippi Burning' left out". Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved May 2, 2016.

- 1 2 Russell, Candace (January 20, 1989). "Julian Bond Disputes Portrayal Of FBI". Sun-Sentinel. Tribune Publishing. Retrieved April 29, 2016.

- ↑ Handelman, David. "'Do the Right Thing': Insight to Riot". Rolling Stone. Retrieved April 29, 2016.

- ↑ Craft, Stephanie; Davis, Charles N. (2013). "The Foundations of Free Expression". Principles of American Journalism: An Introduction. Routledge. p. 189. ISBN 0-415-89017-9.

- 1 2 "1988 Archives – National Board of Review". National Board of Review. National Board of Review. Retrieved February 4, 2015.

- ↑ Voland, John (January 5, 1989). "'Working Girl', 'L.A. Law' Top Globe Choices". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved May 16, 2015.

- ↑ Easton, Nina J. (January 30, 1989). "'Rain Man' Sends a Global Message". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved May 16, 2015.

- ↑ Cipely, Michael (February 16, 1988). "Academy Showers 'Rain Man' With 8 Oscar Bids : 'Dangerous Liaisons' and 'Mississippi Burning' Get 7 Each". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved April 29, 2016.

- 1 2 "The 61st Academy Awards (1989) Nominees and Winners". Oscars.org. Retrieved 2013-11-27.

- 1 2 "Film in 1990". British Academy of Film and Television Arts. Retrieved April 29, 2016.

- ↑ "AFI's 100 Years...100 Cheers Nominees" (PDF). American Film Institute. Retrieved August 14, 2016.

- ↑ MacMinn, Aleene; Puig, Claudia (March 20, 1989). "Kudos". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved April 29, 2016.

- ↑ "The ASC -- Past ASC Awards". American Society of Cinematographers. Retrieved April 29, 2016.

- ↑ "Berlinale: 1989 Prize Winners". berlinale.de. Retrieved 2011-03-12.

- ↑ "BSC Best Cinematography Award". British Society of Cinematographers. Retrieved April 30, 2016.

- ↑ "1989 Artios Awards". Casting Society of America. Retrieved April 29, 2016.

- ↑ "Chicago Film Critics Awards - 1988-97". Chicago Film Critics Association. Retrieved April 29, 2016.

- ↑ Enrico Lancia. I premi del cinema. Gremese Editore, 1998. ISBN 88-7742-221-1.

- ↑ "1988 Directors Guild of America Awards". Directors Guild of America Awards. Retrieved April 29, 2016.

- ↑ "KCFCC Award Winners – 1980–89". Kansas City Film Critics Circle Awards. Retrieved April 29, 2016.

- ↑ Easton, Nina J. (December 12, 1988). "L.A. Film Critics Vote Lahti, Hanks, 'Dorrit' Winners". Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved April 30, 2016.

- ↑ "Winners & Nominees 1989 (Golden Globes)". Golden Globe Awards. Hollywood Foreign Press Association. Retrieved April 30, 2016.

- ↑ Kehr, Dave (January 9, 1989). "'Unbearable Lightness' Named Best Film Of '88 By Critics Group". Chicago Tribune. Chicago Tribune. Retrieved April 30, 2016.

- ↑ Boyar, Jay (January 25, 1989). "Critics' Picks Are Oscar Indicators". Orlando Sentinel. Orlando Sentinel. Retrieved April 30, 2016.

- ↑ "Political Film Society - Previous Award Winners". Political Film Society. Political Film Society. Retrieved April 30, 2016.

Further reading

- Cagin, Seth; Dray, Philip (1988). We Are Not Afraid: The Story of Goodman, Schwerner and Chaney and the Civil Rights Campaign for Mississippi. Macmillan Publishing Company. pp. 289, 290, 294 & 295. ISBN 0-02-520260-X.

- Ranalli, Ralph (July 28, 2001). Deadly Alliance: The FBI's Secret Partnership with the Mob. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-380-81193-9.

- Spain, David M.D. (1964). "Mississippi Autopsy" (PDF). Ramparts Magazine's Mississippi Eyewitness. pp. 43–49.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Mississippi Burning |

- Official Website

- Mississippi Burning at AlanParker.com

- Mississippi Burning at the Internet Movie Database

- Mississippi Burning at AllMovie

- Mississippi Burning at Rotten Tomatoes

- Mississippi Burning at Metacritic

- Mississippi Burning at Box Office Mojo