Tautavel Man

| Tautavel Man | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Primates |

| Family: | Hominidae |

| Genus: | Homo |

| Species: | †H. erectus |

| Subspecies: | †H. e. tautavelensis |

| Trinomial name | |

| Homo erectus tautavelensis de Lumley and de Lumley 1971[1] | |

| |

| Site of discovery in Tautavel, France | |

Tautavel Man (Homo erectus tautavelensis), is a proposed subspecies of the hominid Homo erectus, the 450,000-year-old fossil remains of whom were discovered in the Arago Cave in Tautavel, France. Excavations began in 1964, with the first notable discovery occurring in 1969.[2]

History of excavations

The first person to find objects at the location did so during 1828. These were animal bones considered antediluvian by Marcel de Serres, a professional geologist at the University of Montpellier.[3] The Proto-Mousterian Industry tools[4] found by Jean Abélanet during 1963, initiated the beginning of the Lumley led excavations of 1964.[5]

Discovery and representative fossils

The skeletal remains of two individual hominids have been found in the cave: a female older than 40 (Arago II, July 1969), and a male aged no more than 20 (Arago XXI, July 1971, and Arago XLVII, July 1979).[1] Recovered stone tools originate from within a 5 kilometres (3.1 mi) radius of the cave, while animal bones suggest the inhabitants could travel up to 33 kilometres (21 mi) for food.[6]

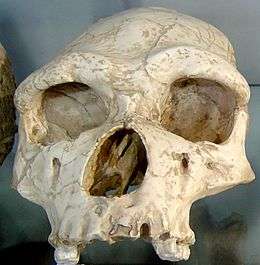

All fossils recovered from Arago were found by Henry and Marie-Antoinette de Lumley and are now located at the Institute for Human Palaeontology in Paris. Arago II is a nearly complete mandible with six teeth from a 40–55 years old female. Arago XXI is a deformed cranial fragment featuring the most complete pre-Neanderthal face accompanied by a frontal and a sphenoid bone. Arago XLVII is a right parietal bone, the sutures of which fits perfectly with Arago XXI. The two latter have an estimated developmental age of twenty, while an uranium series dating produced a fossil age of c.400,000 years (this is near the maximum limit for this method and the fossil may be older.)[1]

The male skull has a flat and receding forehead with well-developed supraorbital ridges ("eyebrows") and a large face with rectangular eye sockets. The cranial cavity had a volume of 1,150 cubic centimetres (70 cu in). The rest of the skeleton has been reconstructed from 75 fossil remains and casts from fossils found at other sites; an interpretation suggesting in a sturdier skeleton than that of modern humans and a height of 1.65 metres (5 ft 5 in).[7][8]

Through the thousands of years from the time that Arago XXI died, changes occurred to the structure of the bone known as "taphonomic transformations", these modifying the shape of skull.[9] These had caused parts of the bone to become slightly bent,[10] including the front of the skull to lose symmetry.[11] Three-dimensional imaging using computers allowed a morphometric analysis of the skull and this was used to compare with skull dimensions of Homo sapiens sapiens and also to obtain a computer generated image of the hominids face.[9]

Compared to H. erectus in North Africa and China, H. erectus tautavelensis is closer to early H. sapiens and thus form a morphologically distinct group together with other European Middle Pleistocene hominids found in Steinheim, Swanscombe, and Pontnewydd, because they show some of the characteristics of Neanderthals. The oldest indirect evidence of hominids in Europe are date to perhaps 1 to 2 million years ago and while Arago is certainly younger, the stalagmite floor under the cave deposits has been ambiguously dated to 700,000 years old by electron spin resonance but to 300,000 years old by thermoluminescence. No signs of fire, ash, charcoal, burned stone, or clay is documented in the cave which seems to suggest the art of fire is a recent discovery, though traces at a 1 to 4 million years old erectus site in East Africa indicate the opposite.[12]

Arago XXI

Arago XXI is a deformed cranial fragment dated to approximately 450,000 years. The skull was found by H. Lumley and M.A. Lumley in the Arago Cave located at Tautavel France.[13] The hominid was twenty years old as indicated by the state of the fronto-pariental suture, and the gender is thought to be male.[2][14][15][16]

Archaeologists were uncertain of the age of the hominid, although finding the morphology comparable to the Petralona skull that is accepted as a Neanderthal of the Upper Pleistocene variate,[17] paleoanthropologists (Cartmill, Smith, et al) have classified the skull instead as Heidelberg.[18][19]

Ecology

The people of the cave ate elk, fallow deer, reindeer, musk ox, bison, Hemitragus bonali (bonal tahr),[20] argali, chamois and Stephanorhinus kirchbergensis.[12][21][22] Bones of Cervus elaphus acoronatus and Cervus elaphoids, two species of deer, Canis etruscus (wolf), and Ursus deningeri, were the most found animal remains in reducing order of number of findings by percentage in the interglacial stage, in the glacial stage the most were Equus mosbachensis (horse),[23] and Ovis ammon antiqua (non-extant mouflon), (plus C. e. acoronatus), and additionally remains of Hemitragus bosali.[24][25]

Arago Cave

Occupied from 600,000 to 400,000 B.P.,[26] the cave is of the earliest known from the middle Pleistocene to archaeology of the Pyrenees.[27] Scraper and chopper tools found within the cave were of the Tayacian Industry.[28][29] The current cave dimensions are smaller than those from the time when the hominid inhabited the cave, the current measurements being 30 metres long and between 10 and 15 metres wide.[30][31] During 2007 the Institut de Paléontologie de Humaine and the Centre Européen Recherche de Pre-historique de Tautavel, both having charge of the site, contacted the ENSG in order to construct a three dimensional model of the cave.[31]

Images

|

See also

References

- 1 2 3 Wood, Bernard A. Wiley-Blackwell encyclopedia of human evolution. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 1-4051-5510-8. Retrieved January 2012. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - 1 2 "The major phases of the discovery". Ministère de la Culture et de la Communication. Retrieved January 2012. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ "Marcel de Serres" (in French). Tela Botanica et Réseau Ecole et Nature. 2006. Retrieved 2012-01-05.

- ↑ Boardman, John (1982). "1". The Cambridge ancient history: The prehistory of the Balkans; and the Middle East and the Aegean world, tenth to eighth centuries B.C. 3. Cambridge University Press. p. 79. ISBN 0-521-22496-9. Retrieved February 2012. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ "The Arago Cave". Ministère de la Culture et de la Communication. Retrieved January 2012. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ "Arago Cave, Languedoc-Roussillon, France". Archaeology Travel. Retrieved January 2012. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ "The Tautavel Man". Ministère de la culture et de la communication. Retrieved January 2012. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ Ranzi, C. "The Reconstruction of the Tautavel Man". Ministère de la culture et de la communication. Retrieved January 2012. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - 1 2 Subsol, G.; Mafart, B.; Silvestre, A.; de Lumley, M.A. (2002). "3D Image Processing for the Study of the Evolution of the Shape of the Human Skull: Presentation of the Tools and Preliminary Results". In B. Mafart; H. Delingette; G. Subsol. Three-Dimensional Imaging in Paleoanthropology and Prehistoric Archaeology (pdf). BAR International Series 1049. pp. 37–45. Retrieved February 2012. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ Ponce de León & Zollikofer 1999

- ↑ Mafart et al. 1999

- 1 2 Chippindale, Christopher (9 Oct 1986). "At home with the first Europeans". New Scientist: 38–42. Retrieved January 2012. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ (Smithsonian museum)[Retrieved 2012-01-01]

- ↑ Seidler, H.; Falk, D.; Stringer, C.; Wilfing, H.; Müller, G. B.; Zur Nedden, D.; Weber, G. W.; Reicheis, W.; Arsuaga, J. L. (1997). "A comparative study of stereolithographically modelled skulls of Petralona and Broken Hill: Implications for future studies of middle Pleistocene hominid evolution". Journal of Human Evolution. 33 (6): 691–703. doi:10.1006/jhev.1997.0163. PMID 9467776.

- ↑ Winfried Henke, Thorolf Hardt Handbook of paleoanthropology, Volume 1 Springer, 29 May 2007 ISBN 3-540-32474-7 [Retrieved 2012-01-01]

- ↑ Homme de Tautavel (Homo erectus) (in French) Hominidés.com [Retrieved 2012-01-01]

- ↑ Stringer, C. B. (1974). "A multivariate study of the Petralona skull". Journal of Human Evolution. 3 (5): 397–201. doi:10.1016/0047-2484(74)90202-4.

- ↑ Matt Cartmill, Fred H. Smith The human lineage Volume 2 of Foundation of Human Biology John Wiley and Sons, 30 Mar 2009 ISBN 0-471-21491-4 [Retrieved 2012-01-01]

- ↑ Poulianos, Aris N. Pre-Sapiens Man in Greece . Current Anthropology, Vol. 22, No. 3 (Jun., 1981), pp. 287-288.

- ↑ "A photographic collection of the world's Caprinae". IUCN/SSC - Caprinae Specialist Group.

- ↑ Billia, Emmanuel M. E. (2006). "The skull of Stephanorhinus kirchbergensis (Jäger, 1839) (Mammalia, Rhinocerotidae) from Irkutsk Province, Eastern Siberia" (pdf). Russian J. Theriol. 5 (2): 63–71.

- ↑ Ministère de la Culture et de la Communication [NAVIGATION] to the information shown from this link is > THE ENVIRONMENT > FAUNA [Retrieved 2012-01-04]

- ↑ Bellai, Driss (1998). "Le Cheval du Gisement de Pléiscène de moyen de la caune l'Arago (Tautavel Pyrénées Orientales France)". Quaternaire. 9 (4): 325–335. doi:10.3406/quate.1998.1614. Retrieved 2 January 2012.

- ↑ Jourdan and Moigne 1981

- ↑ Gamble, Clive (1999). The palaeolithic societies of Europe. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-65872-1. Retrieved 2 January 2012.

- ↑ Espinasse, Guillaume; Pérès, Dimitri (January 2009). "Fouilles d'été à Tautavel" (pdf) (in French). 283. Saga Information. Retrieved 2012-01-05.

- ↑ Byrne, Louise (April 2004). "Lithic tools from Arago cave, Tautavel (Pyrénées-Orientales, France): behavioural continuity or raw material determinism during the Middle Pleistocene?". Journal of Archaeological Science. 31 (4): 351–364. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2003.07.008.

- ↑ "Tautavel man". Encyclopaedia Britannica. 1995. Retrieved 2012-01-04.

- ↑ John Wymer (1982). "Specialised hunter gatherers". The Palaeolithic Age. Taylor & Francis. pp. 121–122. ISBN 0-7099-2710-X. Retrieved 2012-01-04.

- ↑ "The Arago Cave". Ministère de la Culture et de la Communication. Retrieved 2012-01-03.

- 1 2 Chandalier, L.; Roche, F. "Terrestrial laser scanning for paleontologists: The Tautavel Cave" (pdf). Ecole National des Science Géographiques. Retrieved 5 January 2012.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Arago Cave. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Collection of prehistory of the Musée de Préhistoire de Tautavel. |

- Blumenfeld, Jodi. "La Caune de l'Arago, Tautavel, France (August 2000)". Retrieved January 2012. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) (Image from the excavations at Tautavel in 2000) - Ministère de la Culture et de la Communication site - provides navigation through the information obtained by the Arago cave excavations [Retrieved 2011-01-02]

- Human Timeline (Interactive) – Smithsonian, National Museum of Natural History (August 2016).