Genotype

The genotype is the part (DNA sequence) of the genetic makeup of a cell, and therefore of an organism or individual, which determines a specific characteristic (phenotype) of that cell/organism/individual.[1] Genotype is one of three factors that determine phenotype, the other two being inherited epigenetic factors, and non-inherited environmental factors. DNA mutations which are acquired rather than inherited, such as cancer mutations, are not part of the individual's genotype; hence, scientists and physicians sometimes talk for example about the (geno)type of a particular cancer, that is the genotype of the disease as distinct from the diseased.

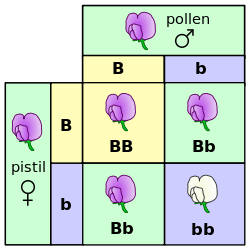

An example of how genotype determines a characteristic is petal color in a pea plant.

Genotypic and genomic sequence

The genotype of an organism is the inherited map it carries within its genetic code. Not all organisms with the same genotype look or act the same way because appearance and behavior are modified by environmental and developmental conditions. Likewise, not all organisms that look alike necessarily have the same genotype. One's genotype differs subtly from one's genomic sequence. A sequence is an absolute measure of base composition of an individual, or a representative of a species or group; a genotype typically implies a measurement of how an individual differs or is specialized within a group of individuals or a species. So typically, one refers to an individual's genotype with regard to a particular gene of interest and, in polyploid individuals, it refers to what combination of alleles the individual carries (see homozygous, heterozygous). The genetic constitution of an organism is referred to as its genotype, such as the letters Bb. (B - dominant genotype and b - recessive genotype)

Genotype and phenotype

Any given gene will usually cause an observable change in an organism, known as the phenotype. The terms genotype and phenotype are distinct for at least two reasons:

- To distinguish the source of an observer's knowledge (one can know about genotype by observing DNA; one can know about phenotype by observing outward appearance of an organism).

- Genotype and phenotype are not always directly correlated. Some genes only express a given phenotype in certain environmental conditions. Conversely, some phenotypes could be the result of multiple genotypes. The genotype is commonly mixed up with the phenotype which describes the end result of both the genetic and the environmental factors giving the observed expression (e.g. blue eyes, hair color, or various hereditary diseases).

A simple example to illustrate genotype as distinct from phenotype is the flower colour in pea plants (see Gregor Mendel). There are three available genotypes, PP (homozygous dominant), Pp (heterozygous), and pp (homozygous recessive). All three have different genotypes but the first two have the same phenotype (purple) as distinct from the third (white).

A more technical example to illustrate genotype is the single nucleotide polymorphism or SNP. A SNP occurs when corresponding sequences of DNA from different individuals differ at one DNA base, for example where the sequence AAGCCTA changes to AAGCTTA. This contains two alleles : C and T. SNPs typically have three genotypes, denoted generically AA Aa and aa. In the example above, the three genotypes would be CC, CT and TT. Other types of genetic marker, such as microsatellites, can have more than two alleles, and thus many different genotypes.

Genotype and Mendelian inheritance

The distinaction between genotype and phenotype is commonly experienced when studying family patterns for certain hereditary diseases or conditions, for example, haemophilia. Due to the diploidy of humans (and most animals), there are two alleles for any given gene. These alleles can be the same (homozygous) or different (heterozygous), depending on the individual (see zygote). With a dominant allele, the offspring is guaranteed to inherit the trait in question irrespective of the second allele.

In the case of an albino with a recessive allele (aa), the phenotype depends upon the other allele (Aa, aA, aa or AA). An affected person mating with a heterozygous individual (Aa or aA, also carrier) there is a 50-50 chance the offspring will be albino's phenotype. If a heterozygote mates with another heterozygote, there is 75% chance passing the gene on and only a 25% chance that the gene will be displayed. A homozygous dominant (AA) individual has a normal phenotype and no risk of abnormal offspring. A homozygous recessive individual has an abnormal phenotype and is guaranteed to pass the abnormal gene onto offspring.

In the case of haemophilia, it is sex-linked thus only carried on the X chromosome. Only females can be a carrier in which the abnormality is not displayed. This woman has a normal phenotype, but runs a 50-50 chance, with an unaffected partner, of passing her abnormal gene on to her offspring. If she mated with a man with haemophilia (another carrier) there would be a 75% chance of passing on the gene.

Determining genotype

Genotyping is the process of elucidating the genotype of an individual with a biological assay. Also known as a genotypic assay, techniques include PCR, DNA fragment analysis, allele specific oligonucleotide (ASO) probes, DNA sequencing, and nucleic acid hybridization to DNA microarrays or beads. Several common genotyping techniques include restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP), terminal restriction fragment length polymorphism (t-RFLP),[2] amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP),[3] and multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification (MLPA).[4]

DNA fragment analysis can also be used to determine such disease causing genetics aberrations as microsatellite instability (MSI),[5] trisomy[6] or aneuploidy, and loss of heterozygosity (LOH).[7] MSI and LOH in particular have been associated with cancer cell genotypes for colon, breast and cervical cancer.

The most common chromosomal aneuploidy is a trisomy of chromosome 21 which manifests itself as Down syndrome. Current technological limitations typically allow only a fraction of an individual’s genotype to be determined efficiently.

See also

- Endophenotype

- Nucleic acid sequence

- Potentiality and actuality

- Quaternary numeral system

- Sequence (biology)

References

- ↑ "Genotype definition - Medical Dictionary definitions". medterms.com.

- ↑ Hulce, David; Liu, ChangSheng (Jonathan) (July 2006). "SoftGenetics Application Note - GeneMarker® Software for Terminal-Restriction Fragment Length Polymorphism (T-RFLP) Data Analysis" (PDF). SoftGenetics.

- ↑ "Keygene.com Homepage"

- ↑ "SoftGenetics Application Note - Software for Multiplex Ligation-dependent Probe Amplification (MLPA™)" (PDF). SoftGenetics. April 2006. Retrieved 2011-03-13.

- ↑ He, Haiguo; Ning, Wan; Liu, Jonathan (March 2007). "SoftGenetics Application Note - Microsatellite Instability Analysis with GeneMarker® Tamela Serensits" (PDF). SoftGenetics.

- ↑ "SoftGenetics Application Note - GeneMarker® Software for Trisomy Analysis" (PDF). SoftGenetics. November 2006.

- ↑ Serensits, Pamela; He, Haiguo, Ning, Wan; Liu, Jonathan (March 2007). "SoftGenetics Application Note - Loss of Heterozygosity Detection with GeneMarker" (PDF). SoftGenetics.

External links

| Look up genotype, phenotype, inheritance, or genome in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Genotypes. |