Flowering plant

| Flowering plants Temporal range: Early Cretaceous - recent, 120–0 Ma | |

|---|---|

| |

| Magnolia virginiana, sweet bay | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Subkingdom: | Embryophyta |

| (unranked): | Spermatophyta |

| (unranked): | Angiosperms |

| Groups | |

|

According to APG IV (2016):[1]

Traditional groups: | |

| Synonyms | |

The flowering plants (angiosperms), also known as Angiospermae[4][5] or Magnoliophyta,[6] are the most diverse group of land plants, with 416 families, approx. 13,164 known genera and a total of c. 295,383 known species.[7] Like gymnosperms, angiosperms are seed-producing plants; they are distinguished from gymnosperms by characteristics including flowers, endosperm within the seeds, and the production of fruits that contain the seeds. Etymologically, angiosperm means a plant that produces seeds within an enclosure, in other words, a fruiting plant. The term "angiosperm" comes from the Greek composite word (angeion, "case" or "casing", and sperma, "seed") meaning "enclosed seeds", after the enclosed condition of the seeds.

The ancestors of flowering plants diverged from gymnosperms in the Triassic Period, during the range 245 to 202 million years ago (mya), and the first flowering plants are known from 160 mya. They diversified extensively during the Lower Cretaceous, became widespread by 120 mya, and replaced conifers as the dominant trees from 100 to 60 mya.

Angiosperm derived characteristics

Angiosperms differ from other seed plants in several ways, described in the table. These distinguishing characteristics taken together have made the angiosperms the most diverse and numerous land plants and the most commercially important group to humans.[lower-alpha 1]

| Feature | Description |

|---|---|

| Flowering organs | Flowers, the reproductive organs of flowering plants, are the most remarkable feature distinguishing them from the other seed plants. Flowers provided angiosperms with the means to have a more species-specific breeding system, and hence a way to evolve more readily into different species without the risk of crossing back with related species. Faster speciation enabled the Angiosperms to adapt to a wider range of ecological niches. This has allowed flowering plants to largely dominate terrestrial ecosystems. |

| Stamens with two pairs of pollen sacs | Stamens are much lighter than the corresponding organs of gymnosperms and have contributed to the diversification of angiosperms through time with adaptations to specialized pollination syndromes, such as particular pollinators. Stamens have also become modified through time to prevent self-fertilization, which has permitted further diversification, allowing angiosperms eventually to fill more niches. |

| Reduced male parts, three cells | The male gametophyte in angiosperms is significantly reduced in size compared to those of gymnosperm seed plants. The smaller size of the pollen reduces the amount of time between pollination — the pollen grain reaching the female plant — and fertilization. In gymnosperms, fertilization can occur up to a year after pollination, whereas in angiosperms, fertilization begins very soon after pollination.[8] The shorter amount of time between pollination and fertilization allows angiosperms to produce seeds earlier after pollination than gymnosperms, providing angiosperms a distinct evolutionary advantage. |

| Closed carpel enclosing the ovules (carpel or carpels and accessory parts may become the fruit) | The closed carpel of angiosperms also allows adaptations to specialized pollination syndromes and controls. This helps to prevent self-fertilization, thereby maintaining increased diversity. Once the ovary is fertilized, the carpel and some surrounding tissues develop into a fruit. This fruit often serves as an attractant to seed-dispersing animals. The resulting cooperative relationship presents another advantage to angiosperms in the process of dispersal. |

| Reduced female gametophyte, seven cells with eight nuclei | The reduced female gametophyte, like the reduced male gametophyte, may be an adaptation allowing for more rapid seed set, eventually leading to such flowering plant adaptations as annual herbaceous life-cycles, allowing the flowering plants to fill even more niches. |

| Endosperm | In general, endosperm formation begins after fertilization and before the first division of the zygote. Endosperm is a highly nutritive tissue that can provide food for the developing embryo, the cotyledons, and sometimes the seedling when it first appears. |

Evolution

Fossilized spores suggest that higher plants (embryophytes) have lived on land for at least 475 million years.[9] Early land plants reproduced sexually with flagellated, swimming sperm, like the green algae from which they evolved. An adaptation to terrestrialization was the development of upright meiosporangia for dispersal by spores to new habitats. This feature is lacking in the descendants of their nearest algal relatives, the Charophycean green algae. A later terrestrial adaptation took place with retention of the delicate, avascular sexual stage, the gametophyte, within the tissues of the vascular sporophyte. This occurred by spore germination within sporangia rather than spore release, as in non-seed plants. A current example of how this might have happened can be seen in the precocious spore germination in Selaginella, the spike-moss. The result for the ancestors of angiosperms was enclosing them in a case, the seed. The first seed bearing plants, like the ginkgo, and conifers (such as pines and firs), did not produce flowers. The pollen grains (males) of Ginkgo and cycads produce a pair of flagellated, mobile sperm cells that "swim" down the developing pollen tube to the female and her eggs.

The apparently sudden appearance of nearly modern flowers in the fossil record initially posed such a problem for the theory of evolution that Charles Darwin called it an "abominable mystery".[10] However, the fossil record has considerably grown since the time of Darwin, and recently discovered angiosperm fossils such as Archaefructus, along with further discoveries of fossil gymnosperms, suggest how angiosperm characteristics may have been acquired in a series of steps. Several groups of extinct gymnosperms, in particular seed ferns, have been proposed as the ancestors of flowering plants, but there is no continuous fossil evidence showing exactly how flowers evolved. Some older fossils, such as the upper Triassic Sanmiguelia, have been suggested. Based on current evidence, some propose that the ancestors of the angiosperms diverged from an unknown group of gymnosperms in the Triassic period (245–202 million years ago). Fossil angiosperm-like pollen from the Middle Triassic (247.2–242.0 Ma) suggests an older date for their origin.[11] A close relationship between angiosperms and gnetophytes, proposed on the basis of morphological evidence, has more recently been disputed on the basis of molecular evidence that suggest gnetophytes are instead more closely related to other gymnosperms.

The evolution of seed plants and later angiosperms appears to be the result of two distinct rounds of whole genome duplication events.[12] These occurred at 319 million years ago and 192 million years ago. Another possible whole genome duplication event at 160 million years ago perhaps created the ancestral line that led to all modern flowering plants.[13] That event was studied by sequencing the genome of an ancient flowering plant, Amborella trichopoda,[14] and directly addresses Darwin's "abominable mystery."

The earliest known macrofossil confidently identified as an angiosperm, Archaefructus liaoningensis, is dated to about 125 million years BP (the Cretaceous period),[15] whereas pollen considered to be of angiosperm origin takes the fossil record back to about 130 million years BP. However, one study has suggested that the early-middle Jurassic plant Schmeissneria, traditionally considered a type of ginkgo, may be the earliest known angiosperm, or at least a close relative.[16] In addition, circumstantial chemical evidence has been found for the existence of angiosperms as early as 250 million years ago. Oleanane, a secondary metabolite produced by many flowering plants, has been found in Permian deposits of that age together with fossils of gigantopterids.[17][18] Gigantopterids are a group of extinct seed plants that share many morphological traits with flowering plants, although they are not known to have been flowering plants themselves.

In 2013 flowers encased in amber were found and dated 100 million years before present. The amber had frozen the act of sexual reproduction in the process of taking place. Microscopic images showed tubes growing out of pollen and penetrating the flower's stigma. The pollen was sticky, suggesting it was carried by insects.[19]

Recent DNA analysis based on molecular systematics[20][21] showed that Amborella trichopoda, found on the Pacific island of New Caledonia, belongs to a sister group of the other flowering plants, and morphological studies[22] suggest that it has features that may have been characteristic of the earliest flowering plants.

The orders Amborellales, Nymphaeales, and Austrobaileyales diverged as separate lineages from the remaining angiosperm clade at a very early stage in flowering plant evolution.[23]

The great angiosperm radiation, when a great diversity of angiosperms appears in the fossil record, occurred in the mid-Cretaceous (approximately 100 million years ago). However, a study in 2007 estimated that the division of the five most recent (the genus Ceratophyllum, the family Chloranthaceae, the eudicots, the magnoliids, and the monocots) of the eight main groups occurred around 140 million years ago.[24] By the late Cretaceous, angiosperms appear to have dominated environments formerly occupied by ferns and cycadophytes, but large canopy-forming trees replaced conifers as the dominant trees only close to the end of the Cretaceous 66 million years ago or even later, at the beginning of the Tertiary.[25] The radiation of herbaceous angiosperms occurred much later.[26] Yet, many fossil plants recognizable as belonging to modern families (including beech, oak, maple, and magnolia) had already appeared by the late Cretaceous.

It is generally assumed that the function of flowers, from the start, was to involve mobile animals in their reproduction processes. That is, pollen can be scattered even if the flower is not brightly colored or oddly shaped in a way that attracts animals; however, by expending the energy required to create such traits, angiosperms can enlist the aid of animals and, thus, reproduce more efficiently.

Island genetics provides one proposed explanation for the sudden, fully developed appearance of flowering plants. Island genetics is believed to be a common source of speciation in general, especially when it comes to radical adaptations that seem to have required inferior transitional forms. Flowering plants may have evolved in an isolated setting like an island or island chain, where the plants bearing them were able to develop a highly specialized relationship with some specific animal (a wasp, for example). Such a relationship, with a hypothetical wasp carrying pollen from one plant to another much the way fig wasps do today, could result in the development of a high degree of specialization in both the plant(s) and their partners. Note that the wasp example is not incidental; bees, which, it is postulated, evolved specifically due to mutualistic plant relationships, are descended from wasps.[27]

Animals are also involved in the distribution of seeds. Fruit, which is formed by the enlargement of flower parts, is frequently a seed-dispersal tool that attracts animals to eat or otherwise disturb it, incidentally scattering the seeds it contains (see frugivory). Although many such mutualistic relationships remain too fragile to survive competition and to spread widely, flowering proved to be an unusually effective means of reproduction, spreading (whatever its origin) to become the dominant form of land plant life.

Flower ontogeny uses a combination of genes normally responsible for forming new shoots.[28] The most primitive flowers probably had a variable number of flower parts, often separate from (but in contact with) each other. The flowers tended to grow in a spiral pattern, to be bisexual (in plants, this means both male and female parts on the same flower), and to be dominated by the ovary (female part). As flowers evolved, some variations developed parts fused together, with a much more specific number and design, and with either specific sexes per flower or plant or at least "ovary-inferior".

Flower evolution continues to the present day; modern flowers have been so profoundly influenced by humans that some of them cannot be pollinated in nature. Many modern domesticated flower species were formerly simple weeds, which sprouted only when the ground was disturbed. Some of them tended to grow with human crops, perhaps already having symbiotic companion plant relationships with them, and the prettiest did not get plucked because of their beauty, developing a dependence upon and special adaptation to human affection.[29]

A few paleontologists have also proposed that flowering plants, or angiosperms, might have evolved due to interactions with dinosaurs. One of the idea's strongest proponents is Robert T. Bakker. He proposes that herbivorous dinosaurs, with their eating habits, provided a selective pressure on plants, for which adaptations either succeeded in deterring or coping with predation by herbivores.[30]

Classification

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The phylogeny of the flowering plants, as of APG III (2009).[31] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Alternative phylogeny (2010)[32] |

There are eight groups of living angiosperms:

- Amborella, a single species of shrub from New Caledonia;

- Nymphaeales, about 80 species,[33] water lilies and Hydatellaceae;

- Austrobaileyales, about 100 species[33] of woody plants from various parts of the world;

- Chloranthales, several dozen species of aromatic plants with toothed leaves;

- Magnoliids, about 9,000 species,[33] characterized by trimerous flowers, pollen with one pore, and usually branching-veined leaves—for example magnolias, bay laurel, and black pepper;

- Monocots, about 70,000 species,[33] characterized by trimerous flowers, a single cotyledon, pollen with one pore, and usually parallel-veined leaves—for example grasses, orchids, and palms;

- Ceratophyllum, about 6 species[33] of aquatic plants, perhaps most familiar as aquarium plants;

- Eudicots, about 175,000 species,[33] characterized by 4- or 5-merous flowers, pollen with three pores, and usually branching-veined leaves—for example sunflowers, petunia, buttercup, apples, and oaks.

The exact relationship between these eight groups is not yet clear, although there is agreement that the first three groups to diverge from the ancestral angiosperm were Amborellales, Nymphaeales, and Austrobaileyales.[34] The term basal angiosperms refers to these three groups. Among the rest, the relationship between the three broadest of these groups (magnoliids, monocots, and eudicots) remains unclear. Some analyses make the magnoliids the first to diverge, others the monocots.[32] Ceratophyllum seems to group with the eudicots rather than with the monocots.

APG IV classification

Based on the 4th version of the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group classification.[1]

| Angiosperm classification | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

History of classification

The botanical term "Angiosperm", from the Ancient Greek αγγείον, angeíon (bottle, vessel) and σπέρμα, (seed), was coined in the form Angiospermae by Paul Hermann in 1690, as the name of one of his primary divisions of the plant kingdom. This included flowering plants possessing seeds enclosed in capsules, distinguished from his Gymnospermae, or flowering plants with achenial or schizo-carpic fruits, the whole fruit or each of its pieces being here regarded as a seed and naked. The term and its antonym were maintained by Carl Linnaeus with the same sense, but with restricted application, in the names of the orders of his class Didynamia. Its use with any approach to its modern scope became possible only after 1827, when Robert Brown established the existence of truly naked ovules in the Cycadeae and Coniferae,[35] and applied to them the name Gymnosperms. From that time onward, as long as these Gymnosperms were, as was usual, reckoned as dicotyledonous flowering plants, the term Angiosperm was used antithetically by botanical writers, with varying scope, as a group-name for other dicotyledonous plants.

In 1851, Hofmeister discovered the changes occurring in the embryo-sac of flowering plants, and determined the correct relationships of these to the Cryptogamia. This fixed the position of Gymnosperms as a class distinct from Dicotyledons, and the term Angiosperm then gradually came to be accepted as the suitable designation for the whole of the flowering plants other than Gymnosperms, including the classes of Dicotyledons and Monocotyledons. This is the sense in which the term is used today.

In most taxonomies, the flowering plants are treated as a coherent group. The most popular descriptive name has been Angiospermae (Angiosperms), with Anthophyta ("flowering plants") a second choice. These names are not linked to any rank. The Wettstein system and the Engler system use the name Angiospermae, at the assigned rank of subdivision. The Reveal system treated flowering plants as subdivision Magnoliophytina (Frohne & U. Jensen ex Reveal, Phytologia 79: 70 1996), but later split it to Magnoliopsida, Liliopsida, and Rosopsida. The Takhtajan system and Cronquist system treat this group at the rank of division, leading to the name Magnoliophyta (from the family name Magnoliaceae). The Dahlgren system and Thorne system (1992) treat this group at the rank of class, leading to the name Magnoliopsida. The APG system of 1998, and the later 2003[36] and 2009[31] revisions, treat the flowering plants as a clade called angiosperms without a formal botanical name. However, a formal classification was published alongside the 2009 revision in which the flowering plants form the Subclass Magnoliidae.[37]

The internal classification of this group has undergone considerable revision. The Cronquist system, proposed by Arthur Cronquist in 1968 and published in its full form in 1981, is still widely used but is no longer believed to accurately reflect phylogeny. A consensus about how the flowering plants should be arranged has recently begun to emerge through the work of the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group (APG), which published an influential reclassification of the angiosperms in 1998. Updates incorporating more recent research were published as APG II in 2003[36] and as APG III in 2009.[31][38]

Traditionally, the flowering plants are divided into two groups, which in the Cronquist system are called Magnoliopsida (at the rank of class, formed from the family name Magnoliaceae) and Liliopsida (at the rank of class, formed from the family name Liliaceae). Other descriptive names allowed by Article 16 of the ICBN include Dicotyledones or Dicotyledoneae, and Monocotyledones or Monocotyledoneae, which have a long history of use. In English a member of either group may be called a dicotyledon (plural dicotyledons) and monocotyledon (plural monocotyledons), or abbreviated, as dicot (plural dicots) and monocot (plural monocots). These names derive from the observation that the dicots most often have two cotyledons, or embryonic leaves, within each seed. The monocots usually have only one, but the rule is not absolute either way. From a broad diagnostic point of view, the number of cotyledons is neither a particularly handy nor a reliable character.

Recent studies, as by the APG, show that the monocots form a monophyletic group (clade) but that the dicots do not (they are paraphyletic). Nevertheless, the majority of dicot species do form a monophyletic group, called the eudicots or tricolpates. Of the remaining dicot species, most belong to a third major clade known as the magnoliids, containing about 9,000 species. The rest include a paraphyletic grouping of primitive species known collectively as the basal angiosperms, plus the families Ceratophyllaceae and Chloranthaceae.

Flowering plant diversity

The number of species of flowering plants is estimated to be in the range of 250,000 to 400,000.[39][40][41] This compares to around 12,000 species of moss[42] or 11,000 species of pteridophytes,[43] showing that the flowering plants are much more diverse. The number of families in APG (1998) was 462. In APG II[36] (2003) it is not settled; at maximum it is 457, but within this number there are 55 optional segregates, so that the minimum number of families in this system is 402. In APG III (2009) there are 415 families.[31][44]

The diversity of flowering plants is not evenly distributed. Nearly all species belong to the eudicot (75%), monocot (23%), and magnoliid (2%) clades. The remaining 5 clades contain a little over 250 species in total; i.e. less than 0.1% of flowering plant diversity, divided among 9 families. The 42 most-diverse of 443 families of flowering plants by species,[45] in their APG circumscriptions, are

- Asteraceae or Compositae (daisy family): 22,750 species;

- Orchidaceae (orchid family): 21,950;

- Fabaceae or Leguminosae (bean family): 19,400;

- Rubiaceae (madder family): 13,150;[46]

- Poaceae or Gramineae (grass family): 10,035;

- Lamiaceae or Labiatae (mint family): 7,175;

- Euphorbiaceae (spurge family): 5,735;

- Melastomataceae or Melastomaceae (melastome family): 5,005;

- Myrtaceae (myrtle family): 4,625;

- Apocynaceae (dogbane family): 4,555;

- Cyperaceae (sedge family): 4,350;

- Malvaceae (mallow family): 4,225;

- Araceae (arum family): 4,025;

- Ericaceae (heath family): 3,995;

- Gesneriaceae (gesneriad family): 3,870;

- Apiaceae or Umbelliferae (parsley family): 3,780;

- Brassicaceae or Cruciferae (cabbage family): 3,710:

- Piperaceae (pepper family): 3,600;

- Acanthaceae (acanthus family): 3,500;

- Rosaceae (rose family): 2,830;

- Boraginaceae (borage family): 2,740;

- Urticaceae (nettle family): 2,625;

- Ranunculaceae (buttercup family): 2,525;

- Lauraceae (laurel family): 2,500;

- Solanaceae (nightshade family): 2,460;

- Campanulaceae (bellflower family): 2,380;

- Arecaceae (palm family): 2,361;

- Annonaceae (custard apple family): 2,220;

- Caryophyllaceae (pink family): 2,200;

- Orobanchaceae (broomrape family): 2,060;

- Amaranthaceae (amaranth family): 2,050;

- Iridaceae (iris family): 2,025;

- Aizoaceae or Ficoidaceae (ice plant family): 2,020;

- Rutaceae (rue family): 1,815;

- Phyllanthaceae (phyllanthus family): 1,745;

- Scrophulariaceae (figwort family): 1,700;

- Gentianaceae (gentian family): 1,650;

- Convolvulaceae (bindweed family): 1,600;

- Proteaceae (protea family): 1,600;

- Sapindaceae (soapberry family): 1,580;

- Cactaceae (cactus family): 1,500;

- Araliaceae (Aralia or ivy family): 1,450.

Of these, the Orchidaceae, Poaceae, Cyperaceae, Arecaceae, and Iridaceae are monocot families; Piperaceae, Lauraceae, and Annonaceae are magnoliid dicots; the rest of the families are eudicots.

Vascular anatomy

1. Pith,

2. Protoxylem,

3. Xylem I,

4. Phloem I,

5. Sclerenchyma (bast fibre),

6. Cortex,

7. Epidermis

The amount and complexity of tissue-formation in flowering plants exceeds that of gymnosperms. The vascular bundles of the stem are arranged such that the xylem and phloem form concentric rings.

In the dicotyledons, the bundles in the very young stem are arranged in an open ring, separating a central pith from an outer cortex. In each bundle, separating the xylem and phloem, is a layer of meristem or active formative tissue known as cambium. By the formation of a layer of cambium between the bundles (interfascicular cambium), a complete ring is formed, and a regular periodical increase in thickness results from the development of xylem on the inside and phloem on the outside. The soft phloem becomes crushed, but the hard wood persists and forms the bulk of the stem and branches of the woody perennial. Owing to differences in the character of the elements produced at the beginning and end of the season, the wood is marked out in transverse section into concentric rings, one for each season of growth, called annual rings.

Among the monocotyledons, the bundles are more numerous in the young stem and are scattered through the ground tissue. They contain no cambium and once formed the stem increases in diameter only in exceptional cases.

The flower, fruit, and seed

Flowers

The characteristic feature of angiosperms is the flower. Flowers show remarkable variation in form and elaboration, and provide the most trustworthy external characteristics for establishing relationships among angiosperm species. The function of the flower is to ensure fertilization of the ovule and development of fruit containing seeds. The floral apparatus may arise terminally on a shoot or from the axil of a leaf (where the petiole attaches to the stem). Occasionally, as in violets, a flower arises singly in the axil of an ordinary foliage-leaf. More typically, the flower-bearing portion of the plant is sharply distinguished from the foliage-bearing or vegetative portion, and forms a more or less elaborate branch-system called an inflorescence.

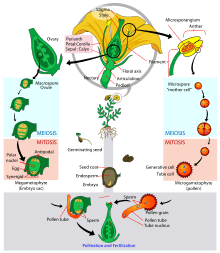

There are two kinds of reproductive cells produced by flowers. Microspores, which will divide to become pollen grains, are the "male" cells and are borne in the stamens (or microsporophylls). The "female" cells called megaspores, which will divide to become the egg cell (megagametogenesis), are contained in the ovule and enclosed in the carpel (or megasporophyll).

The flower may consist only of these parts, as in willow, where each flower comprises only a few stamens or two carpels. Usually, other structures are present and serve to protect the sporophylls and to form an envelope attractive to pollinators. The individual members of these surrounding structures are known as sepals and petals (or tepals in flowers such as Magnolia where sepals and petals are not distinguishable from each other). The outer series (calyx of sepals) is usually green and leaf-like, and functions to protect the rest of the flower, especially the bud. The inner series (corolla of petals) is, in general, white or brightly colored, and is more delicate in structure. It functions to attract insect or bird pollinators. Attraction is effected by color, scent, and nectar, which may be secreted in some part of the flower. The characteristics that attract pollinators account for the popularity of flowers and flowering plants among humans.

While the majority of flowers are perfect or hermaphrodite (having both pollen and ovule producing parts in the same flower structure), flowering plants have developed numerous morphological and physiological mechanisms to reduce or prevent self-fertilization. Heteromorphic flowers have short carpels and long stamens, or vice versa, so animal pollinators cannot easily transfer pollen to the pistil (receptive part of the carpel). Homomorphic flowers may employ a biochemical (physiological) mechanism called self-incompatibility to discriminate between self and non-self pollen grains. In other species, the male and female parts are morphologically separated, developing on different flowers.

Fertilization and embryogenesis

Double fertilization refers to a process in which two sperm cells fertilize cells in the ovary. This process begins when a pollen grain adheres to the stigma of the pistil (female reproductive structure), germinates, and grows a long pollen tube. While this pollen tube is growing, a haploid generative cell travels down the tube behind the tube nucleus. The generative cell divides by mitosis to produce two haploid (n) sperm cells. As the pollen tube grows, it makes its way from the stigma, down the style and into the ovary. Here the pollen tube reaches the micropyle of the ovule and digests its way into one of the synergids, releasing its contents (which include the sperm cells). The synergid that the cells were released into degenerates and one sperm makes its way to fertilize the egg cell, producing a diploid (2n) zygote. The second sperm cell fuses with both central cell nuclei, producing a triploid (3n) cell. As the zygote develops into an embryo, the triploid cell develops into the endosperm, which serves as the embryo's food supply. The ovary will now develop into a fruit and the ovule will develop into a seed.

Fruit and seed

As the development of embryo and endosperm proceeds within the embryo sac, the sac wall enlarges and combines with the nucellus (which is likewise enlarging) and the integument to form the seed coat. The ovary wall develops to form the fruit or pericarp, whose form is closely associated with the manner of distribution of the seed.

Frequently, the influence of fertilization is felt beyond the ovary, and other parts of the flower take part in the formation of the fruit, e.g., the floral receptacle in the apple, strawberry, and others.

The character of the seed coat bears a definite relation to that of the fruit. They protect the embryo and aid in dissemination; they may also directly promote germination. Among plants with indehiscent fruits, in general, the fruit provides protection for the embryo and secures dissemination. In this case, the seed coat is only slightly developed. If the fruit is dehiscent and the seed is exposed, in general, the seed-coat is well developed, and must discharge the functions otherwise executed by the fruit.

Economic importance

Agriculture is almost entirely dependent on angiosperms, which provide virtually all plant-based food, and also provide a significant amount of livestock feed. Of all the families of plants, the Poaceae, or grass family (grains), is by far the most important, providing the bulk of all feedstocks (rice, corn — maize, wheat, barley, rye, oats, pearl millet, sugar cane, sorghum). The Fabaceae, or legume family, comes in second place. Also of high importance are the Solanaceae, or nightshade family (potatoes, tomatoes, and peppers, among others), the Cucurbitaceae, or gourd family (also including pumpkins and melons), the Brassicaceae, or mustard plant family (including rapeseed and the innumerable varieties of the cabbage species Brassica oleracea), and the Apiaceae, or parsley family. Many of our fruits come from the Rutaceae, or rue family (including oranges, lemons, grapefruits, etc.), and the Rosaceae, or rose family (including apples, pears, cherries, apricots, plums, etc.).

In some parts of the world, certain single species assume paramount importance because of their variety of uses, for example the coconut (Cocos nucifera) on Pacific atolls, and the olive (Olea europaea) in the Mediterranean region.

Flowering plants also provide economic resources in the form of wood, paper, fiber (cotton, flax, and hemp, among others), medicines (digitalis, camphor), decorative and landscaping plants, and many other uses. The main area in which they are surpassed by other plants — namely, coniferous trees (Pinales), which are non-flowering (gymnosperms) — is timber and paper production.

See also

- List of garden plants

- List of plant orders

- List of plants by common name

- List of systems of plant taxonomy

Notes

- ↑ The major exception to the dominance of terrestrial ecosystems by flowering plants is the coniferous forest.

References

- 1 2 Angiosperm Phylogeny Group (2016), "An update of the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group classification for the orders and families of flowering plants: APG IV", Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society, 181 (1): 1–20, doi:10.1111/boj.12385, retrieved 2016-05-20

- ↑ Cronquist 1960.

- ↑ Takhtajan 1964.

- ↑ Lindley, J (1830). Introduction to the Natural System of Botany. London: Longman, Rees, Orme, Brown, and Green. xxxvi.

- ↑ Cantino, Philip D.; Doyle, James A.; Graham, Sean W.; Judd, Walter S.; Olmstead, Richard G.; Soltis, Douglas E.; Soltis, Pamela S.; Donoghue, Michael J. (2007). "Towards a phylogenetic nomenclature of Tracheophyta". Taxon. 56 (3): E1–E44. doi:10.2307/25065865.

- ↑ Cronquist (1988). Magnoliophyta Flowering Plants.

- ↑ Christenhusz, M. J. M.; Byng, J. W. (2016). "The number of known plants species in the world and its annual increase". Phytotaxa. Magnolia Press. 261 (3): 201–217. doi:10.11646/phytotaxa.261.3.1.

- ↑ Williams, J.H. (2012). "The evolution of pollen germination timing in flowering plants: Austrobaileya scandens (Austrobaileyaceae)". AoB Plants. 2012 (http://aobpla.oxfordjournals.org/content/2012/pls010.abstract). doi:10.1093/aobpla/pls010.

- ↑ Edwards, D (2000). "The role of mid-palaeozoic mesofossils in the detection of early bryophytes". Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 355 (1398): 733–755. doi:10.1098/rstb.2000.0613. PMC 1692787

. PMID 10905607.

. PMID 10905607. - ↑ Davies, T. J. (2004). "Darwin's abominable mystery: Insights from a supertree of the angiosperms". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 101 (7): 1904–9. doi:10.1073/pnas.0308127100. PMC 357025

. PMID 14766971.

. PMID 14766971. - ↑ Hochuli, P. A.; Feist-Burkhardt, S. (2013). "Angiosperm-like pollen and Afropollis from the Middle Triassic (Anisian) of the Germanic Basin (Northern Switzerland)". Front. Plant Sci. 4: 344. doi:10.3389/fpls.2013.00344.

- ↑ Jiao, Yuannian; Wickett, No4rman J.; Ayyampalayam, Saravanaraj; Chanderbali, André S.; et al. (2011). "Ancestral polyploidy in seed plants and angiosperms". Nature. 473 (7345): 97–100. doi:10.1038/nature09916. PMID 21478875.

- ↑ Ewen Callaway (December 2013). "Shrub genome reveals secrets of flower power". Nature. doi:10.1038/nature.2013.14426.

- ↑ Keith Adams (December 2013). "Genomic Clues to the Ancestral Flowering Plant". Science. 342 (6165): 1456–1457. doi:10.1126/science.1248709.

- ↑ Sun, G.; Ji, Q.; Dilcher, D.L.; Zheng, S.; Nixon, K.C.; Wang, X. (2002). "Archaefructaceae, a New Basal Angiosperm Family". Science. 296 (5569): 899–904. doi:10.1126/science.1069439. PMID 11988572.

- ↑ Wing, Xin; Duan, Shuying; Geng, Baoyin; Cui, Jinzhong; Yang, Yong (2007). "Schmeissneria: A missing link to angiosperms?". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 7: 14. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-7-14. PMC 1805421

. PMID 17284326.

. PMID 17284326. - ↑ Taylor, David Winship; Li, Hongqi; Dahl, Jeremy; Fago, Fred J.; Zinniker, David; Moldowan, J. Michael (2006). "Biogeochemical evidence for the presence of the angiosperm molecular fossil oleanane in Paleozoic and Mesozoic non-angiospermous fossils". Paleobiology. 32 (2): 179. doi:10.1666/0094-8373(2006)32[179:BEFTPO]2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0094-8373.

- ↑ Oily Fossils Provide Clues To The Evolution Of Flowers — ScienceDaily (April 5, 2001)

- ↑ Poinar Jr., George O; Chambers, Kenton L; Wunderlich, Joerg (10 December 2013). "Micropetasos, a new genus of angiosperms from mid-Cretaceous Burmese amber" (PDF). J. Bot. Res. Inst. Texas. 7 (2): 745–750. Lay summary (3 January 2014).

- ↑ NOVA — Transcripts — First Flower — PBS Airdate: April 17, 2007

- ↑ Soltis, D. E.; Soltis, P. S. (2004). "Amborella not a "basal angiosperm"? Not so fast". American Journal of Botany. 91 (6): 997–1001. doi:10.3732/ajb.91.6.997. PMID 21653455.

- ↑ South Pacific plant may be missing link in evolution of flowering plants — Public release date: 17 May 2006

- ↑ Vialette-Guiraud, AC; Alaux, M; Legeai, F; Finet, C; et al. (2011). "Cabomba as a model for studies of early angiosperm evolution". Annals of Botany. 108 (4): 589–98. doi:10.1093/aob/mcr088. PMC 3170152

. PMID 21486926.

. PMID 21486926. - ↑ Moore, M. J.; Bell, C. D.; Soltis, P. S.; Soltis, D. E. (2007). "Using plastid genome-scale data to resolve enigmatic relationships among basal angiosperms". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 104 (49): 19363–8. doi:10.1073/pnas.0708072104. PMC 2148295

. PMID 18048334.

. PMID 18048334. - ↑ David Sadava; H. Craig Heller; Gordon H. Orians; William K. Purves; David M. Hillis (December 2006). Life: the science of biology. Macmillan. pp. 477–. ISBN 978-0-7167-7674-1. Retrieved 4 August 2010.

- ↑ Stewart, Wilson Nichols; Rothwell, Gar W. (1993). Paleobotany and the evolution of plants (2nd ed.). Cambridge Univ. Press. p. 498. ISBN 0-521-23315-1.

- ↑ Buchmann, Stephen L.; Nabhan, Gary Paul (2012). The Forgotten Pollinators. Island Press. pp. 41–42. ISBN 978-1-59726-908-7.

- ↑ Age-Old Question On Evolution Of Flowers Answered — 15-Jun-2001

- ↑ Human Affection Altered Evolution of Flowers — By Robert Roy Britt, LiveScience Senior Writer (posted: 26 May 2005 06:53 am ET)

- ↑ Bakker, Robert T. (17 August 1978). "Dinosaur Feeding Behaviour and the Origin of Flowering Plants". Nature. London: Macmillan. 274 (5672): 661–663. doi:10.1038/274661a0.

- 1 2 3 4 Angiosperm Phylogeny Group (2009). "An update of the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group classification for the orders and families of flowering plants: APG III". Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society. 161 (2): 105–121. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8339.2009.00996.x. Retrieved 2010-12-10.

- 1 2 Bell, C.D.; Soltis, D.E. & Soltis, P.S. (2010). "The Age and Diversification of the Angiosperms Revisited". American Journal of Botany. 97 (8): 1296–1303. doi:10.3732/ajb.0900346. PMID 21616882., p. 1300

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Jeffrey D. Palmer; Douglas E. Soltis; Mark W. Chase (2004). "The plant tree of life: an overview and some points of view". American Journal of Botany. 91 (10): 1437–1445. doi:10.3732/ajb.91.10.1437. PMID 21652302., Figure 2

- ↑ Pamela S. Soltis; Douglas E. Soltis (2004). "The origin and diversification of angiosperms". American Journal of Botany. 91 (10): 1614–1626. doi:10.3732/ajb.91.10.1614. PMID 21652312.

- ↑ Brown R., Character and description of Kingia, a new genus of plants found on the southwest coast of New Holland: with observations on the structure of its unimpregnated ovulum; and on the female flower of Cycadeae and Coniferae, in: King P.P.(Ed.) Narrative of a Survey of the Intertropical and western coasts of Australia, performed between years 1818 and 1822. John Murray, London, 1827, vol. 2., pp. 534–565, .

- 1 2 3 Angiosperm Phylogeny Group (2003). "An update of the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group classification for the orders and families of flowering plants: APG II". Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society. 141 (4): 399–436. doi:10.1046/j.1095-8339.2003.t01-1-00158.x.

- ↑ Chase, Mark W. & Reveal, James L. (2009). "A phylogenetic classification of the land plants to accompany APG III". Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society. 161 (2): 122–127. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8339.2009.01002.x. | Chase & Reveal 2009

- ↑ "As easy as APG III - Scientists revise the system of classifying flowering plants". The Linnean Society of London. 2009-10-08. Retrieved 2009-10-02.

- ↑ Thorne, R. F. (2002). "How many species of seed plants are there?". Taxon. 51 (3): 511–522. doi:10.2307/1554864. JSTOR 1554864.

- ↑ Scotland, R. W.; Wortley, A. H. (2003). "How many species of seed plants are there?". Taxon. 52 (1): 101–104. doi:10.2307/3647306. JSTOR 3647306.

- ↑ Govaerts, R. (2003). "How many species of seed plants are there? – a response". Taxon. 52 (3): 583–584. doi:10.2307/3647457. JSTOR 3647457.

- ↑ Goffinet, Bernard; William R. Buck (2004). "Systematics of the Bryophyta (Mosses): From molecules to a revised classification". Monographs in Systematic Botany. Missouri Botanical Garden Press. 98: 205–239.

- ↑ Raven, Peter H., Ray F. Evert, & Susan E. Eichhorn, 2005. Biology of Plants, 7th edition. (New York: W. H. Freeman and Company). ISBN 0-7167-1007-2.

- ↑ Frank Harold Trevor Rhodes (1 January 1974). Evolution. Golden Press. p. 123. ISBN 978-0-307-64360-5.

- ↑ Stevens, P.F. (2011). "Angiosperm Phylogeny Website (at Missouri Botanical Garden)".

- ↑ "Kew Scientist 30 (October2006)" (PDF).

Bibliography

- Becker, Kenneth M. (February 1973). "A Comparison of Angiosperm Classification Systems". Taxon. 22 (1): 19–50. doi:10.2307/1218032.

- Cronquist, Arthur (October 1960). "The divisions and classes of plants". The Botanical Review. 26 (4): 425–482. doi:10.1007/BF02940572.

- Cronquist, Arthur (1981). An Integrated System of Classification of Flowering Plants. New York: Columbia Univ. Press. ISBN 0-231-03880-1.

- Dahlgren, R. M. T. (February 1980). "A revised system of classification of the angiosperms". Botanical Journal of the Linnean Society. 80 (2): 91–124. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8339.1980.tb01661.x.

- Heywood, V. H., Brummitt, R. K., Culham, A. & Seberg, O. (2007). Flowering Plant Families of the World. Richmond Hill, Ontario, Canada: Firefly Books. ISBN 1-55407-206-9.

- Dilcher, D. (2000). "Toward a new synthesis: Major evolutionary trends in the angiosperm fossil record". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 97 (13): 7030. doi:10.1073/pnas.97.13.7030.

- Pooja (2004). Angiosperms. New Delhi: Discovery. ISBN 9788171417889. Retrieved 7 January 2016.

- Takhtajan, A. (June 1964). "The Taxa of the Higher Plants above the Rank of Order". Taxon. 13 (5): 160–164. doi:10.2307/1216134. JSTOR 10.2307/1216134.

- Simpson, M.G. Plant Systematics, 2nd Edition. Elsevier/Academic Press. 2010.

- Raven, P.H., R.F. Evert, S.E. Eichhorn. Biology of Plants, 7th Edition. W.H. Freeman. 2004.

- Sattler, R. 1973. Organogenesis of Flowers. A Photographic Text-Atlas. University of Toronto Press.

- Zeng, Liping; Zhang, Qiang; Sun, Renran; Kong, Hongzhi; Zhang, Ning; Ma, Hong (24 September 2014). "Resolution of deep angiosperm phylogeny using conserved nuclear genes and estimates of early divergence times". Nature Communications. 5 (4956). doi:10.1038/ncomms5956.

- Cole, Theodor C.H.; Hilger, Dr. Harmut H. Angiosperm Phylogeny Poster – Flowering Plant Systematics

- Cromie, William J. (December 16, 1999). "Oldest Known Flowering Plants Identified By Genes". Harvard University Gazette.

- Watson, L. and Dallwitz, M.J. (1992 onwards). The families of flowering plants: descriptions, illustrations, identification, information retrieval.

- Flowering plant at the Encyclopedia of Life

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Magnoliophyta. |

| Wikispecies has information related to: Magnoliophyta |

| The Wikibook Dichotomous Key has a page on the topic of: Magnoliophyta |

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "article name needed". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "article name needed". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.