Petal

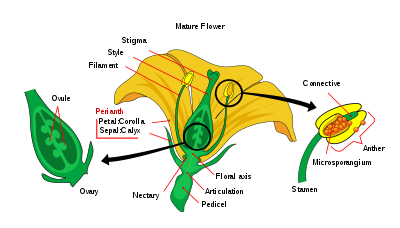

Petals are modified leaves that surround the reproductive parts of flowers. They are often brightly colored or unusually shaped to attract pollinators. Together, all of the petals of a flower are called a corolla. Petals are usually accompanied by another set of special leaves called sepals, that collectively form the calyx and lie just beneath the corolla. The calyx and the corolla together make up the perianth. When the petals and sepals of a flower are difficult to distinguish, they are collectively called tepals. Examples of plants in which the term tepal is appropriate include genera such as Aloe and Tulipa. Conversely, genera such as Rosa and Phaseolus have well-distinguished sepals and petals. When the undifferentiated tepals resemble petals, they are referred to as "petaloid", as in petaloid monocots, orders of monocots with brightly coloured tepals. Since they include Liliales, an alternative name is lilioid monocots.

Although petals are usually the most conspicuous parts of animal-pollinated flowers, wind-pollinated species, such as the grasses, either have very small petals or lack them entirely.

Corolla

The role of the corolla in plant evolution has been studied extensively since Charles Darwin postulated a theory of the origin of elongated corollae and corolla tubes.[1]

If the petals are free from one another in the corolla, the plant is polypetalous or choripetalous; while if the petals are at least partially fused together, it is gamopetalous or sympetalous. The corolla in some plants forms a tube.

Variations

Petals can differ dramatically in different species. The number of petals in a flower may hold clues to a plant's classification. For example, flowers on eudicots (the largest group of dicots) most frequently have four or five petals while flowers on monocots have three or six petals, although there are many exceptions to this rule.[2]

The petal whorl or corolla may be either radially or bilaterally symmetrical (see Symmetry in biology and Floral symmetry). If all of the petals are essentially identical in size and shape, the flower is said to be regular or actinomorphic (meaning "ray-formed"). Many flowers are symmetrical in only one plane (i.e., symmetry is bilateral) and are termed irregular or zygomorphic (meaning "yoke-" or "pair-formed"). In irregular flowers, other floral parts may be modified from the regular form, but the petals show the greatest deviation from radial symmetry. Examples of zygomorphic flowers may be seen in orchids and members of the pea family.

In many plants of the aster family such as the sunflower, Helianthus annuus, the circumference of the flower head is composed of ray florets. Each ray floret is anatomically an individual flower with a single large petal. Florets in the centre of the disc typically have no or very reduced petals. In some plants such as Narcissus the lower part of the petals or tepals are fused to form a floral cup (hypanthium) above the ovary, and from which the petals proper extend.[3][4][5]

Petal often consists of two parts: the upper, broad part, similar to leaf blade, called the limb and the lower part, narrow, similar to leaf petiole, called the claw. Claws are developed in petals of some flowers of the family Brassicaceae, such as Erysimum cheiri.[6]

The inception and further development of petals shows a great variety of patterns.[7] Petals of different species of plants vary greatly in colour or colour pattern, both in visible light and in ultraviolet. Such patterns often function as guides to pollinators, and are variously known as nectar guides, pollen guides, and floral guides.

Genetics

The genetics behind the formation of petals, in accordance with the ABC model of flower development, are that sepals, petals, stamens, and carpels are modified versions of each other. It appears that the mechanisms to form petals evolved very few times (perhaps only once), rather than evolving repeatedly from stamens.[8]

Significance of pollination

Pollination is an important step in the sexual reproduction of higher plants. Pollen is produced by the male flower or by the male organs of hermaphroditic flowers.

Pollen does not move on its own and thus requires wind or animal pollinators to disperse the pollen to the stigma (botany) of the same or nearby flowers. However, pollinators are rather selective in determining the flowers they choose to pollinate. This develops competition between flowers and as a result flowers must provide incentives to appeal to pollinators (unless the flower self-pollinates or is involved in wind pollination). Petals play a major role in competing to attract pollinators. Henceforth pollination dispersal could occur and the survival of many species of flowers could prolong.

Functions and purposes of petals

Petals have various functions and purposes depending on the type of plant. In general, petals operate to protect some parts of the flower and attract/repel specific pollinators. Flower Petal Function: This is where the positioning of the flower petals are located on the flower is the corolla e.g. the buttercup having shiny yellow flower petals which contain guidelines amongst the petals in aiding the pollinator towards the nectar. Pollinators have the ability to determine specific flowers they wish to pollinate.[9] Using incentives flowers draw pollinators and set up a mutual relation between each other in which case the pollinators will remember to always guard and pollinate these flowers (unless incentives are not consistently met and competition prevails).[10]

Scent

The petals could produce different scents to allure desirable pollinators and/or repel undesirable pollinators. Some flowers will also mimic the scents produced by materials such as decaying meat, to attract pollinators to them.[11]

Colour

Various colour traits are used by different petals that could attract pollinators that have poor smelling abilities, or that only come out at certain parts of the day. Some flowers are able to change the colour of their petals as a signal to mutual pollinators to approach or keep away.[12]

Shape and size

Furthermore, the shape and size of the flower/petals is important in selecting the type of pollinators they need. For example, large petals and flowers will attract pollinators at a large distance and/or that are large themselves.[12] Collectively the scent, colour and shape of petals all play a role in attracting/repelling specific pollinators and providing suitable conditions for pollinating. Some pollinators include insects, birds, bats and the wind.[12] In some petals, a distinction can be made between a lower narrowed, stalk-like basal part referred to as the claw, and a wider distal part referred to as the blade. Often the claw and blade are at an angle with one another.

Types of pollination

Wind pollination

Wind-pollinated flowers often have small dull petals and produce little or no scent. Some of these flowers will often have no petals at all. Flowers that depend on wind pollination will produce large amounts of pollen because most of the pollen scattered by the wind tends to not reach other flowers.[13]

Attracting insects

Flowers have various regulatory mechanisms in order to attract insects. One such helpful mechanism is the use of colour guiding marks. Insects such as the bee or butterfly can see the ultraviolet marks which are contained on these flowers, acting as an attractive mechanism which is not visible towards the human eye. Many flowers contain a variety of shapes acting to aid with the landing of the visiting insect and also influence the insect to brush against anthers and stigmas (parts of the flower). One such example of a flower is the pōhutukawa (Metrosideros excelsa) which acts to regulate colour within a different way. The pōhutukawa contains small petals also having bright large red clusters of stamens.[12] Another attractive mechanism for flowers is the use of scent which is highly attractive towards humans such as the rose, but some are very fragrant within attracting flies as they have a smell of rotting meat. Dark is another factor in which flowers have grown to adapt these conditions so colour lacks vision at night therefore scent is the solution for flowers which are pollinated by night flying insects such as the moth.[12]

Attracting birds

Flowers are also pollinated by birds and must be large and colorful to be visible against natural scenery. Such bird –pollinated native plants include: Kōwhai (Sophora species), flax (Phormium tenax, harakeke) and kākā beak (Clianthus puniceus, kōwhai ngutu-kākā). Interestingly enough, flowers adapt the mechanism on their petals to change colour in acting as a communicative mechanism for the bird to visit. An example is the tree fuchsia (Fuchsia excorticata, kōtukutuku) which are green when needing to be pollinated and turn red for the birds to stop coming and pollinating the flower.[12]

Bat-pollinated flowers

Flowers can be pollinated by short tailed bats. An example of this is the dactylanthus (Dactylanthus taylorii). This plant has its home under the ground acting the role of a parasite on the roots of forest trees. The dactylanthus has only its flowers pointing to the surface and the flowers lack colour but have the advantage of containing lots of nectar and a very strong scent. These act as a very useful mechanism in attracting the bat.[14]

References

- ↑ L. Anders Nilsson (1988). "The evolution of flowers with deep corolla tubes". Nature. 334 (6178): 147–149. Bibcode:1988Natur.334..147N. doi:10.1038/334147a0.

- ↑ Soltis, Pamela S.; Douglas E. Soltis (2004). "The origin and diversification of angiosperms". American Journal of Botany. 91 (10): 1614–1626. doi:10.3732/ajb.91.10.1614. PMID 21652312.

- ↑ Simpson 2011, p. 365.

- ↑ Foster 2014, Hypanthium.

- ↑ Graham, S. W.; Barrett, S. C. H. (1 July 2004). "Phylogenetic reconstruction of the evolution of stylar polymorphisms in Narcissus (Amaryllidaceae)". American Journal of Botany. 91 (7): 1007–1021. doi:10.3732/ajb.91.7.1007. PMID 21653457. Retrieved 25 October 2014.

- ↑

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Flower". Encyclopædia Britannica. 10: Evangelical Church – Francis Joseph I. (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Flower". Encyclopædia Britannica. 10: Evangelical Church – Francis Joseph I. (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. - ↑ Sattler, R. 1973. Organogenesis of Flowers. A Photographic Text-Atlas. University of Toronto Press.

- ↑ Rasmussen, D. A.; Kramer, E. M.; Zimmer, E. A. (2008). "One size fits all? Molecular evidence for a commonly inherited petal identity program in Ranunculales". American Journal of Botany. 96 (1): 96–109. doi:10.3732/ajb.0800038. PMID 21628178.

- ↑ Cares-Suarez, R, Poch, T, Acevedo, R.F, Acosta-Bravo, I, Pimentel, C, Espinoza, C, Cares, R.A, Munoz, P, Gonzalez, A.V, Botto-Mahan, C (2011) Do pollinators respond in a dose-dependent manner to flower herbivory?: An experimental assessment in Loasa tricolor (Loasaceae). Gayana Botanica, Volume 68, Pages 176-181

- ↑ Chamberlain S.A; Rudgers J.A (2012). "How do plants balance multiple mutualists? Correlations among traits for attracting protective bodyguards and pollinators in cotton (Gossypium)". Evolutionary Ecology. 26: 65–77. doi:10.1007/s10682-011-9497-3.

- ↑ More, M, Cocucci, A.A, Raguso, R.A (2013). "The importance of oligosulfides in the attraction of fly pollinators to the brood-site deceptive species Jaborosa rotacea (Solanaceae)". International Journal of Plant Sciences. 174: 863–876. doi:10.1086/670367.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Science Learning Hub. (2012). The University of Waikato. "Attracting pollinators". Date Retrieved: August 2013.

- ↑ Donald R. Whitehead (1969). "Wind Pollination in the Angiosperms: Evolutionary and Environmental Considerations". Evolution. 23 (1): 28–35. doi:10.2307/2406479.

- ↑ Physics.org (2012). University of Adelaide. "Flightless parrots, burrowing bats helped parasitic Hades flower". Date Retrieved August 2013.

Bibliography

- Simpson, Michael G. (2011). Plant Systematics. Academic Press. ISBN 0-08-051404-9.

- Foster, Tony. "Botany Word of the Day". Phytography. Retrieved 27 November 2014.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Petals. |