Cinema of Colombia

| Cinema of Colombia | |

|---|---|

|

Garras de oro (1926) | |

| Number of screens | 815 (2013)[1] |

| • Per capita | 1.9 per 100,000 (2013)[1] |

| Main distributors |

Cine Colombia 37.9% United International Pictures 34.8% IACSA 16.6%[2] |

| Produced feature films (2013)[3] | |

| Total | 26 |

| Number of admissions (2013)[4] | |

| Total | 43,817,971 |

| National films | 2,163,964 (4.9%) |

| Gross box office (2013)[4] | |

| Total | COP 353 billion |

| National films | COP 15.5 billion (4.4%) |

| Culture of Colombia |

|

|

Art |

Cinema of Colombia refers to the film industry based in Colombia. Colombian cinema began in 1897 and has included silent films, animated films and internationally acclaimed movies. Government support included an effort in the 1970s to develop the state-owned Cinematographic Development Company (Compañía de Fomento Cinematográfico FOCINE) which helped produce some films yet struggled to maintain itself financially viable. FOCINE became defunct in 1993. In 1997 the Colombian congress approved Law 397 of Article 46 or the General Law of Culture with the purpose of supporting the development of the Colombian film industry by creating a film promotion mixed fund called Corporación PROIMAGENES en Movimiento (PROIMAGES in motion Corporation).[5] In 2003 Congress also approved the Law of Cinema which helped to restart the cinematographic industry in Colombia.

History

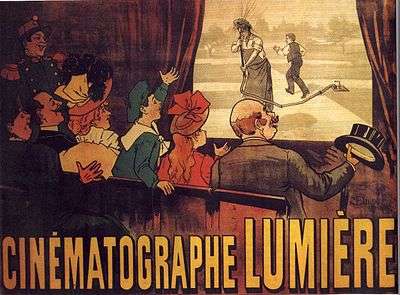

The history of Colombian cinema started in 1897 when the first Cinématographe arrived in the country, two years after the invention of cinematography by Auguste and Louis Lumière in Paris. Back then the port city of Colón (in what today is Panama but was then part of Colombia), Barranquilla, Bucaramanga and later arrived to the capital city of Colombia, Bogotá, where in August of that same year the cinématographe was presented in the Municipal Theater (later demolished).

First years

Soon after the introduction of the cinematographe in Colombia, the country entered a civil war known as the Thousand Days' War causing the suspension of all film production. The first films usually portrayed nature and moments of the Colombian everyday life. The exhibition of these films was dominated by the Di Domenico brothers who owned the Salón Olympia in Bogotá. The Di Domenico Brothers also produced the first film documentary in Colombia called El drama del quince de Octubre (The Drama of October the fifteenth) which was intended to celebrate the centenary of the Battle of Boyacá and also narrated the assassination of General Rafael Uribe Uribe, provoking controversy upon its release.[6]

Silent films

.webm.jpg)

During the early years of Colombian Cinema film producers almost exclusively portrayed nature and everyday life in their films, until 1922, when the first fiction film appeared, titled María (no copies of this film exist anymore). The film was directed by Máximo Calvo Olmedo, a Spanish immigrant who worked as film distributor in Panama and was hired to travel to the city of Cali where he would direct and manage the photography of this film based on the novel by Jorge Isaacs, María.[7]

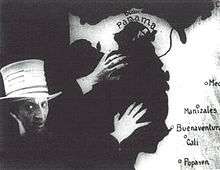

Another pioneer of Colombian cinema was Arturo Acevedo Vallarino a producer and theater director from Antioquia who lived in Bogotá. After the introduction of foreign films and the fascination they caused in Colombia, theaters no longer were as profitable as they once were, and so Acevedo decided to found a film production company called Acevedo e Hijos (Acevedo and sons).[8] Acevedo and sons has been the longest lasting production company in Colombia, existing from 1923 to 1946 and the only one to survive the 1930s' Great Depression. Acevedo and sons produced the films La tragedia del silencio (The Tragedy of Silence) in 1924 and Bajo el Cielo Antioqueño (Under the sky of Antioquia) in 1928. Under the Sky of Antioquia was financed by local magnate Gonzalo Mejía. The film was criticized for being elitist, despite of which it had a somewhat positive acceptance among the public. Films in Colombia were mostly based on themes such as Nature, folklore, and nationalism with some exceptions being literary adaptations. In 1926 the film Garras de oro (Claws of Gold) was released, it has the distinction of being based on a political issue, the separation of Panama from Colombia, and for criticizing the role of the United States in the conflict, both bold firsts in Colombian cinema.[9]

1930s crisis

In 1928 the Colombian company Cine Colombia purchased the Di Domenico film studios, which commercialized international films because of the great profits they promised. International films were preferred before Colombian films by the Colombian public. Because of this, from 1928 until 1940 there was only one film produced in Colombia: Al son de las guitarras (To the Rhythm of the Guitars) by Alberto Santa but it was never shown in theaters. Colombians were more interested in "Hollywood" films. Colombian film industry enthusiasts did not have the money, technology or preparation needed to develop a national cinema. While Colombian movies were still silent, the international industry was already exploiting color and sound films, thus putting the Colombian cinema in a considerable disadvantage.

In the 1940s a businessman from Bogotá called Oswaldo Duperly founded Ducrane Films and produced numerous films despite facing strong competition from Argentine and Mexican cinema which after 1931 drafted to a third position in preference among Colombians.[10] During this time the only production company that survived was the Acevedo and sons until it closed in 1945.

During the 1950s Gabriel García Márquez and Enrique Grau attempted to restart the industry. In 1954 both artists, a writer and a painter respectively created a surrealistic short film La langosta azul (The Blue Lobster). Garcia Marquez continued in the industry as a scriptwriter while Grau continued painting.

'Pornomiseria' cinema

The 'Pornomiseria' (porno-misery) cinema surged during the 1970s to classify the films with a high content of poverty and human misery to make money and gain international recognition. The term was also used in neighboring countries such as Venezuela and Brasil and was intended to criticize the morality of the filmmakers taking this approach. The films that the critics were addressing had gained a lot of attention mainly in European Film Festivals and misrepresented the reality of Latin America. Films like Gamín (1978) by Ciro Durán, a documentary film about children living on the streets, belong to this style and included opinions that were misleading or lacked serious investigation of the social problems they were portraying. This type of film-making was criticized by the Group of Cali, a group of filmmakers mainly represented by Carlos Mayolo and Luis Ospina, which produced the mockumentary "Agarrando Pueblo" (1978), a satire of Pornomiseria films.

Critics of Pornomiseria argued that these films did not treat their subject with profoundness, but took a superficial approach to the issues. Pornomiseria cinema was especially popular in Colombia and Brazil.

Cinematographic Fomenting Company (FOCINE)

On July 28, 1978 the Compañía de Fomento Cinematográfico (FOCINE) (Cinematographic Fomenting Company) was established to administer the Cinematographic Fomenting Fund which had been created a year before, in 1977. FOCINE was first adjudicated to the Colombian Ministry of Communications which in a period of ten years supported 29 films and a number of short films and documentaries. Corruption in its administration led to the closing of FOCINE in 1993.[11] During this period, the work of Carlos Mayolo transcended and introduced new forms of film making into Colombian cinema with the exploration of unconventional languages. Gustavo Nieto Roa helped to develop comedies with an influence from Mexican cinema.

During the last decade of the 20th century, the Colombian government liquidated FOCINE forcing film makers to co-produce films with other countries, mainly from Europe and private capital investors. Despite this, some important productions developed, such as La estrategia del caracol (The Snail's Strategy) by Sergio Cabrera, which won numerous international prizes and managed to revive a national interest on national films. Another successful film director and producer was Víctor Gaviria who, with themes of social concern, created La vendedora de rosas (The Rose Seller) which won many prizes and much recognition along with Bolívar soy yo (I Am Bolívar, 2002) by Jorge Alí Triana.[12]

Law of Cinema

In 2003, the Colombian government passed the Law of Cinema, which standardized help for local film production. Numerous films were sponsored by the government generating a success in the local box office such as Soñar no Cuesta Nada (Dreaming Costs Nothing) by Rodrigo Triana with 1,200,000 spectators, an unprecedented attendance at the time[13] or the film El colombian dream (The Colombian Dream, the last word being in English to highlight a play on the concept of the "American Dream") by Felipe Aljure which achieved technical innovations and employed a narrative never before seen in Colombian cinema.

Law 814 of 2003, also known as the Law of Cinema, was approved after a second debate in the Colombian senate. The senate established the funding of Colombian cinema through taxes collected from distributors, exhibitors and film producers. The collection was set up to be destined to support film producers, short films documentaries and public projects. Funds collected are administered by the PROIMAGENES Cinematographic Production Mixed Fund.[5]

During the second term of President Álvaro Uribe Vélez the government presented a tax reform to cut funding to the Law of Cinema, the president was criticized for this[14] but the minister of Culture Elvira Cuervo de Jaramillo lobbied in the Ministry of Finance to impede this law from affecting the financial resources destined to Colombian cinema. The minister of Finance agreed to protect the benefits for the film industry.[15]

International projection

Colombian cinema has had a very small presence in international events. Despite this, some documentaries during the 1970s had relative success, such as "Chircales" (1972) by Marta Rodríguez and Jorge Silva, which won international prizes and recognition.

During the 1990s Silva gained notoriety with the film La estrategia del caracol (The Strategy of the Snail) and Víctor Gaviria did so with his films Rodrigo D: No futuro (1990) and La vendedora de rosas (1998), which was nominated for a Palme d'Or at the Cannes Film Festival.

In the 2000s (decade) actress Catalina Sandino Moreno was nominated for an Academy Award for her acting in the Colombian American production Maria Full of Grace. She was also nominated for best female acting at the Berlin International Film Festival in 2004 and won, sharing it with actress Charlize Theron.

Documentary films

Documentary productions in Colombia have varied in quality. Nevertheless, they have not seen wide distribution due to barriers which the film industry imposes regarding exhibition and distribution of material. Viewers interested in approaching these audiovisual materials are rare.

During the 1970s, in the city of Cali there was a great "boom" not only in film but in the arts in general. At that time the Grupo de Cali was formed, which would include Carlos Mayolo, Luis Ospina, Andrés Caicedo, Oscar Campo and other documentarists and directors who portrayed a particular sense of place and reality through their work. At the same time, documentarists like Marta Rodríguez and Jorge Silva produced a seemingly unending array of documentaries that approached anthropology, portraying forms of life and realities unknown to many.

Animated film

The development of animated film in Colombia, as in the rest of Latin America, has been slow and irregular, and it is only in recent years that animation has begun to gain importance. The first initiatives in the country were around the 1970s, especially in the production of television commercials. Nonetheless it was at the end of the past decade that Fernando Laverde, considered the pioneer of stop motion animation in Colombia,[16] used experimental methods and limited resources to create short animated pieces that received national and international recognition. Bogota native Carlos Santa explored the world of animated film as fine arts and is considered the father of experimental animation in Colombia. In 1988 with the support of FOCINE[17] Santa released his film El pasajero de la noche (The Passenger of the Night), and in 1994 La selva oscura (The Dark Jungle) at the Caracas Film Festival. Both films received critical recognition for their artistic and narrative merits. In 2010, Carlos Santa completed his first feature-length animated film "Los Extraños Presagios de León Prozak" (The Mysterious Presages of León Prozak) which premiered at the Annecy International Animated Film Festival. In the 2000s (decade) there was renewed activity in Colombian animation thanks to the interest of a new generation in this genre and the emergence of new technology; in 2003 the animated full-length film Bolivar the Hero was released, and the LOOP festival of animation and video games was born, where the work of Colombian and Latin American animators is encouraged and awarded.

Film festivals

Many film festivals take place in Colombia, but the two most important are the Cartagena Film Festival, functioning every year since 1960, and the Bogotá Film Festival, functioning every year since 1984, presenting Latin American and Spanish movies.

Other competitions

Asides from both international festivals, year-round there are encounters, expositions and festivals that encourage audience formation and award local film makers. The most notable are:

- Cien miradas, un país: A hundred eyes, a country, is a Colombian film festival that takes place every year in Colombia and several European cities. The city of Barcelona has hosted in the last two years the festival. During 2013 also add the city of Luxembourg. The event is organized by the Foundation for the Development of Audiovisual Arts - Fundaudiovisuales -

- Eurocine: competition held every year since 1995 in which European films are shown when they are not made available through commercial distribution, the event is organized by the Bogotá offices of the Goethe-Institut, the European commission's delegation in ant the Cinemateca distrital de Bogotá.[18]

- Festival de cine francés: is an exposition of the best of French cinema held every year since 2001 on September and has the backing of the French embassyin Bogotá, Medellín, Cali and Barranquilla, it includes conferences, workshops and roundtables.[19]

- Semana de Cine Colombiano, Sí Futuro: steming from a growth in Colombian film making after the passing of the Law of Cinema, in 2006 an exposition of Colombian cinema was inaugurated with the awarding of noteworthy films, film makers and actors in recent years by an international jury.

- Imaginatón: Is a bi-annual film making and film screening marathon where professionals and amateurs of all ages and nationalities are invited to make a filminuto in plano secuencia, the beszt of which are selected and awarded by a specialized jury. The event is organized by Black Velvet Laboratories, a company dedicated to the field of "audiovisual entertainment analysis and development".[20]

- Festival de Cine y Video de Santa Fe de Antioquia: is a festival that has been taking place since March 2000 by the Film and Video Corporation of de Santa Fe de Antioquia and is directed by film maker Víctor Gaviria with the stated aim of promoting film making and audience forming on the Antioquia region, although film makers from all over the country can participate[21]

- MUDA Colombia: The University Exposition of Audiovisuals (MUDA, for its Spanish abbreviation) Colombia is a contest held yearly where the best in university work is awarded as well as pedagogic technicques proposed by film professors all over the country.[22]

- IN VITRO VISUAL: Is one of the best established short-film-related events in Colombia, it presents Colombian shorts on Tuesdays and foreign ones on Thursdays, chosen out of a yearly contest presided by a jury of veteran film makers. At the end of the event awards are given out along with the event's official statuettes (SANTA LUCIA) as well as cash prizes. This event is organized by Black Velvet Laboratories and In Vitro Producciones.[23]

- LOOP, Festival Latinoamericano de Animación & Videojuegos: is animation festival that seeks to motivate young artists, with an emphasis on digital work. The festival's website has developed into a community which encourages learning and sharing of works.[24]

- CineToro Film Festival: An emerging event dedicated to promote experimentation and independent films. It's an annual festival and has gained great attention for having a strong programming of rare films and remarkable International guests.

Shows and distribution

In Colombia there are four major commercial movie theatre chains: Cine Colombia, Cinemark, Procinal and Royal Films among many other independent movie theaters like the Cinemateca Distrital de Bogotá and Los Acevedos in the Museo de Arte Moderno de Bogotá.

Openings in Colombia

| Year | Box office openings from the Colombian film industry | Foreign box office openings | Total box office openings | Percentage of Colombian box office openings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1993 | 2 | 274 | 276 | 0.72% |

| 1994 | 1 | 267 | 268 | 0.37% |

| 1995 | 2 | 249 | 251 | 0.80% |

| 1996 | 3 | 270 | 273 | 1.10% |

| 1997 | 1 | 251 | 252 | 0.40% |

| 1998 | 6 | 237 | 243 | 2.47% |

| 1999 | 3 | NA | NA | NA |

| 2000 | 4 | 200 | 204 | 1.96% |

| 2001 | 7 | 196 | 203 | 3.45% |

| 2002 | 8 | 176 | 180 | 2.22% |

| 2003 | 5 | 170 | 175 | 2.86% |

| 2004 | 8 | 159 | 167 | 4.79% |

| 2005 | 8 | 156 | 164 | 4.88% |

| 2006 | 8 | 154 | 162 | 4.94% |

| 2007 | 12 | 189 | 198 | 6.06% |

| 2008 | 13 | 200 | 213 | 6.1% |

| 2009 | 12 | 202 | 214 | 5.6% |

| 2010 | 10 | 196 | 206 | 4.9% |

| 2011 | 18 | 188 | 206 | 8.70% |

| 2012 | 22 | 191 | 213 | 10.8% |

| 2013 | 17 | 227 | 244 | 7.07% |

| 2014 | 20 | 274 | 284 | 7.04% |

| 2015 | 37 | 332 | 369 | 10.02% |

Highest-grossing Colombian films

| Rank | Title | Tickets sold | Year |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Colombia, magia salvaje | 1,654,929 | 2015 |

| 2 | Uno al año no hace daño | 1,634,763 | 2014 |

| 3 | La estrategia del caracol | 1,600,000 | 1996 |

| 4 | El Paseo | 1,501,806 | 2010 |

| 5 | El Paseo 2 | 1,431,818 | 2012 |

| 6 | Rosario Tijeras | 1,053,030 | 2005 |

| 7 | Paraíso Travel | 931,245 | 2008 |

| 8 | El Paseo 3 | 825,353 | 2013 |

| 9 | La vendedora de rosas | 700,000 | 1998 |

| 10 | Muertos del susto | 667,640 | 2007 |

See also

References

- 1 2 "Table 8: Cinema Infrastructure - Capacity". UNESCO Institute for Statistics. Retrieved 5 November 2013.

- ↑ "Table 6: Share of Top 3 distributors (Excel)". UNESCO Institute for Statistics. Retrieved 5 November 2013.

- ↑ "Table 1: Feature Film Production - Genre/Method of Shooting". UNESCO Institute for Statistics. Retrieved 5 November 2013.

- 1 2 "Table 11: Exhibition - Admissions & Gross Box Office (GBO)". UNESCO Institute for Statistics. Retrieved 5 November 2013.

- 1 2 Proimagenes en Movimiento: Origen (Spanish) proimagenescolombia.com Accessed 26 August 2007.

- ↑ Luis Ángel Arango Library: Fin del periodo "primitivo" (Spanish) Luis Ángel Arango Library Accessed 26 August 2007.

- ↑ Luis Ángel Arango Library: Calvo, Máximo; Biografía (Spanish) Luis Ángel Arango Library Accessed 26 August 2007.

- ↑ Luis Ángel Arango Library: Entrevista con Gonzalo Acevedo (Spanish) Luis Ángel Arango Library Accessed 26 August 2007.

- ↑ Hernando Martínez Pardo, Historia del Cine Colombiano, Editorial América Latina, pages 50 to 55 and 80.

- ↑ Cuadernos de cine colombiano Nº 23, pages 2–5 March 1987 Publicación periódica de la Cinemateca Distrital, Maria Elvira Talero y otros autores

- ↑ COLARTE: Historia del cine en Colombia (Spanish) Colarte.com Accessed 27 August 2007.

- ↑ Senses of Cinema: Rescuing the Image: The 5th Ibero-American Film Festival, Santa Cruz de la Sierra, Bolivia (Portuguese) Senseofcinema.com Accessed 27 August 2007.

- ↑ Pro Imagenes Colombia: La taquillera Soñar no cuesta nada se lanza en DVD y gana premio del público en Chicago (Spanish) proimagenes colombia.com Accessed 27 August 2007.

- ↑ Colombian newspaper El Tiempo, printed edition of August 20, 2006, pages 2.1 and 2.2

- ↑ MINCULTURA: La Ley de Cine en propuesta de Reforma Tributaria (Spanish) mincultura.gov.co Accessed 26 August 2007.

- ↑ Patrimonio fílmico colombiano, Perfil de Fernando Laverde

- ↑ Revista Kinetoscopio, Págs. 114, 115

- ↑ Festival Eurocine Archived May 9, 2007, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Festival de cine francés

- ↑ "Imaginatón". Imaginaton.net. Retrieved 2011-11-04.

- ↑ "Festival de cine y video de Santa Fe de Antioquia". Festicineantioquia.com. Retrieved 2011-11-04.

- ↑ "MUDA Colombia". MUDA Colombia. Retrieved 2011-11-04.

- ↑ "In Vitro Visual". CO-BO: Blackvelvetlab.com. Retrieved 2011-11-04.

- ↑ "LOOP Festival Latinoamericano de animación y videojuegos". Loop.la. Retrieved 2011-11-04.

- ↑ Exhibición y distribución Archived August 24, 2007, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑

- 1993 - 1999, "Impacto del sector fonográfico sobre la economía colombiana: situación actual y perspectivas" Zuleta, Jaramillo, Reina, Fedesarrollo, 2003.

- ↑

- 2000 - 2006, Dirección de Cinematografía, Cinecolombia

- ↑ http://www.eltiempo.com/entretenimiento/cine-y-tv/analisis-del-cine-colombiano-en-el-2015/16470431

- ↑ "Colombia, Magia salvaje se convirtió en la película colombiana más taquillera de la historia". El Colombiano. Retrieved 26 January 2016.

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: Ley de cine (Colombia) (Spanish) |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cinema of Colombia. |

- (Spanish) Fundación Patrimonio Filmico Colombiano

- (Spanish) Fondo Mixto de Promoción Cinematográfica PROIMAGENES en Movimiento

- (Spanish) Cinemateca Distrital de Bogotá

- (Spanish) Movie Theater of Los Acevedo in the Museum of Modern Arts of MAMBO

- (Spanish) Law of Cinema

- (Spanish) Cartagena Film Festival

- (Spanish) Bogotá Film Festival