Bobbi Campbell

| Bobbi Campbell | |

|---|---|

Bobbi Campbell (left), with his lover Bobby Hilliard, on the cover of Newsweek, August 8, 1983 | |

| Born |

Robert Boyle Campbell, Jr. January 28, 1952 Columbus, Georgia |

| Died |

August 15, 1984 (aged 32) San Francisco, California |

| Cause of death | Cryptosporidiosis, resulting from AIDS |

| Resting place | New Tacoma Cemetery, Tacoma, Washington |

| Nationality | American |

| Other names |

|

| Occupation | Public health nurse |

| Known for | AIDS activism, co-writing the Denver Principles |

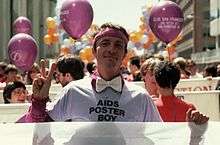

Bobbi Campbell (born Robert Boyle Campbell Jr., January 28, 1952 – August 15, 1984)[1] was a public health nurse and an early United States AIDS activist. In September 1981, Campbell became the 16th person in San Francisco to be diagnosed with Kaposi's sarcoma,[2] when that was a proxy for an AIDS diagnosis.[3] He was the first to come out publicly as a person living with what was to become known as AIDS.[4][5] In 1983, he co-wrote the Denver Principles, the defining manifesto of the People With AIDS Self-Empowerment Movement,[4][6] which he had co-founded the previous year.[4][5] Appearing on the cover of Newsweek and being interviewed on national news reports,[2][7][8] Campbell raised the national profile of the AIDS crisis among heterosexuals and provided a recognizable, optimistic, human face of the epidemic for affected communities.[2]

Before the AIDS crisis

Born in Georgia in 1952[1] and raised in Tacoma, Washington,[9] he gained a degree in nursing from the University of Washington.[10] Having been in the initial wave of gay liberation in Seattle,[11] Campbell moved from Seattle to San Francisco in 1975,[12] getting a job in a hospital near The Castro and immersing himself in the political and social life of the community,[12] which had become a center for the LGBT community over the previous few years. By 1981, he enrolled in a training program at University of California, San Francisco, to become an adult health nurse practitioner,[12] with a view to focusing on healthcare in the gay and lesbian community.[13]

Diagnosis and local activism

Starting with a case of shingles in February 1981,[14] Bobbi Campbell suffered a succession of unusual illnesses, including leukopenia later that summer.[14] After hiking the Pinnacles National Monument with his boyfriend in September that year, he noticed on his feet lesions of Kaposi's sarcoma (KS),[9][14] then thought of as a rare cancer of elderly Jewish men but with alarming numbers of cases appearing in California and New York[3][15] and now known to be closely associated with AIDS. He was formally diagnosed as having KS by dermatologist Marcus Conant on October 8, 1981,[12][14] in what would become Conant's first diagnosis of a patient with AIDS;[8] Campbell brought Conant a rose every year to commemorate the anniversary of his diagnosis.[8]

While the New York Native was printing several stories about the "gay cancer" beginning to make its way round the city, with detailed medical writing by Dr Lawrence D. Mass,[9] the San Francisco gay press largely ignored the nascent epidemic.[9] Campbell's interest in educational outreach and professional interest in gay sexual health combined to inspire him to raise awareness himself.[9]

He put pictures of his KS lesions in the window of the Star Pharmacy at 498 Castro Street, urging men with similar lesions to seek medical attention.[16][17][18] In doing so, he created and posted San Francisco's first AIDS poster.[19] After speaking with Randy Alfred, a friend and editor of the San Francisco Sentinel, Campbell agreed to write a column, "to demystify the AIDS story".[14] In his first article, on December 10, 1981, he proclaimed himself to be the "KS Poster Boy"[9] (later "AIDS Poster Boy"),[7][8][18] becoming the first person in the US to publicly disclose that he was suffering from "gay cancer",[4][5] writing:[9][13]

The purpose of the poster boy is to raise interest and money in a particular cause, and I do have aspirations of doing that regarding gay cancer. I'm writing because I have a determination to live. You do, too — Don't you?

This became a regular column in the Sentinel — and syndicated in gay newspapers nationwide — describing his experiences.[20] On January 10, 1982, Campbell was interviewed by Alfred for The Gay Life program on KSAN-FM, with doctors Marcus Conant and Paul Volberding; the interview has been archived by the GLBT Historical Society[21]

Campbell joined the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence[18][22] at the time of the health crisis in early 1982; in his "sister" persona as Sister Florence Nightmare,[4][19] he co-authored the first San Francisco safer sex manual, Play Fair!, written in plain sex-positive language, using humor to leaven practical advice.[22]

In February 1982, on the invitation of Drs Conant and Volberding,[4][19] Campbell and Dan Turner, who had just himself been diagnosed with KS,[19] attended what turned out to be the founding meeting of the KS/AIDS Foundation, which later became the San Francisco AIDS Foundation,[19] of which Campbell then served on the board.[6] He also became involved with the Shanti Project (which moved from its original focus, supporting people with terminal cancer, to help provide emotional support to people diagnosed with AIDS coming to terms with death)[23][24] and fought to become more available to counsel AIDS patients at Conant's KS clinic.[24]

The People With AIDS Movement

In 1982, Campbell and Turner convened a meeting that spawned People With AIDS San Francisco,[4][5][6] founding the "People With AIDS Self-Empowerment Movement" or PWA Movement,[4][5] rapidly followed by Michael Callen and Richard Berkowitz, authors of How to Have Sex in an Epidemic, in New York City.[6] As well as arguing that People With AIDS should expect to participate actively in the response to the AIDS crisis, the PWA Movement rejected the terms "AIDS victim" and "AIDS patient," as Campbell explained in interviews, for example:[14]

The BAR ran a story on a friend of mine ... the headline read "Coalition treasurer KS victim" and my friend, who is the subject of this interview, was very unhappy because the implication of "KS victim" means the bus has run over you and you're laying there in the street, flattened. And he's very much alive; so am I. I do not feel like a "victim."

With other People With AIDS, Campbell organized the first candlelight march,[5] to bring attention to the plight of people with AIDS and to remember those who had died, marching on May 2, 1983, behind a banner of "Fighting for our lives" for the first time,[4][5] drawing around 10,000 people. On 23 May 1983, People With AIDS San Francisco voted to send Campbell and Turner to the Fifth National Lesbian and Gay Health Conference, at which the Second National AIDS Forum would be held.[4]

Campbell and his colleagues' push to persuade service organizations to sponsor gay men with AIDS to attend the Conference was a key moment in the People With AIDS Self-Empowerment Movement, with Michael Callan subsequently writing:[4][19]

We learned that Bobbi Campbell and others in San Francisco were urging that the major AIDS service providing organizations sponsor one or more gay men with AIDS to enable them to attend the conference.The idea struck like a bolt of lightning. Until then, it simply hadn't occurred to those of us in New York who were diagnosed that we could be anything more than the passive recipients of the genuine care and concern of those who hadn't (yet) been diagnosed. As soon as the concept of PWAs representing themselves was proposed, the idea caught on like wildfire .... Part of the widespread acceptance of the notion of self-empowerment must be attributed to lessons learned from the feminist and civil rights struggles. Many of the earliest and most vocal supporters of the right to self-empowerment were the lesbians and feminists among the AIDS Network attendees.

The national PWA movement came fully together when Campbell took charge of a discussion[4][16][19] where, with Callan, Turner and others,[25] he drafted the Denver Principles, the defining manifesto of the PWA Movement,[4][5][6][18][19] which, again, start with the rejection of the terms "victim" and "patient."[4][6][19] Campbell and the San Franciscans had different thoughts on the origin (etiology) of AIDS from Callan and the New Yorkers — Campbell described as "crazy" the idea that AIDS was caused by promiscuity,[14] a perspective espoused by Callan and Berkowitz (and Dr Joseph Sonnabend) at the time[26][27][28] — and the Denver Principles represent a "careful synthesis" of these two positions:[12]

For example, the "recommendations for all people" would have been easy points of agreement; the last of the "recommendations for people with AIDS," on sexual ethics, underlines their agreements about safe sex but without delving into the language of "promiscuity" or its rebuttals; and the second recommendation for health care providers appears to be a gentle assertion of Callan's concerns about etiology, while the third likely reflects Campbell's own approach to how to be a clinician, and would have been the sort of instruction a progressive nursing educator might have given at the time.

When the activists stormed the stage of the closing session to present the Denver Principles, the "Fighting for our lives" banner from the San Francisco march earlier that month, with the words becoming the slogan of the PWA Movement.[4][16]

After the conference, Campbell flew to New York with Callan, Berkowitz and Artie Felson, plotting on the plane.[4][19] On arrival organized a PWA organization in the city despite initial opposition from the Gay Men's Health Crisis.[4] They also planned a national PWA organization[19] which opened in New York City in June 1984. PWA-New York went on to create the first safer sex poster to appear in a gay bathhouse in the city.[4]

In June 1984, the annual San Francisco's Gay Freedom Day Parade was dedicated for the first time to people with AIDS. Dykes on Bikes have led the parade since the mid-1970s and People With AIDS followed immediately behind.[4]

Wider activism

Campbell also became known outside the gay community, bringing wider attention to the AIDS crisis. Campbell and Dr Conant featured in the earliest nationally broadcast news reports on the "gay cancer" on June 12, 1982, where Barry Petersen interviewed Campbell, Larry Kramer and Dr James W. Curran, who led the CDC taskforce, for CBS News.[29]

The most high-profile early piece, introducing AIDS to the heterosexual community, however was the cover article of the August 8, 1983, edition of Newsweek, showing Campbell and his lover Bobby Hilliard and headlined "EPIDEMIC: The Mysterious and Deadly Disease Called AIDS May Be the Public Health Threat of the Century. How Did it Start? Can it Be Stopped?"[2][8][30] — only the second time an openly gay man had appeared on the cover of a mass-market news magazine,[2][30] albeit with Hilliard identified as Campbell's "friend."[31] The following week, with Callen, Berkowitz, Felson and Turner,[32] he met with Margaret Heckler, Secretary of Health and Human Services in the Reagan administration.[32] They found Heckler to be receptive to suggestions and, when Campbell pushed the issue of delays in People With AIDS's claims for Social Security, she promised to raise it with her counterpart at the Social Security Administration.[32]

On October 7, 1983, Campbell presented a poster session of the first Nursing Clinical Conference on AIDS in Washington, D.C., dressed in white pants and a lab coat, to "dress for the part,"[31][32] in order to help clinicians and nurses understand the Denver Principles' message about respect for People With AIDS, rather than considering them as "victims."[31][32] While at the conference, he attended a talk by an infection control nurse at the National Institutes of Health where he discovered the agency's "maximum awareness" policy recommended the use of electric-green "AIDS Precaution" tags on AIDS patients' rooms, blood tubes and laundry.[32] With Artie Felson, he heckled from the back and arranged an impromptu meeting of the National Association of People With AIDS, where they decided to pay visit to Heckler at her Bethesda office and spoke with Shelley Lengel, a spokesperson for the new National AIDS Helpline. Lengel, however, did not call them back with further information about the policy.[32]

In January 1984, when Dan White, the assassin of gay San Francisco Supervisor Harvey Milk and Mayor George Moscone, was due to be paroled, Campbell and Hilliard stood outside Soledad State Prison.[8] As White had been transported to Los Angeles for fear of retributive attacks,[33][34][35] attendant media had little to cover beyond Campbell with a sign reading "Dan White's homophobia is more deadly than AIDS,"[8] bringing further national attention to the health crisis.[8]

In June 1984, Campbell traveled with Angie Lewis to New Orleans for the annual convention of the American Nursing Association, where they gave a 45-minute or hour-long presentation — possibly a plenary session — about AIDS and HIV, having been invited at the last minute; Lewis suggested this may have been because the ANA were unsure about hosting the session.[36]

In July 1984, Campbell gave one of his last speeches at the National March for Lesbian and Gay Rights at the 1984 Democratic National Convention in San Francisco.[37] He was introduced as a feminist, a registered Democrat and a Person With AIDS; he had served as a board director of the National AIDS Foundation and on the steering committee of the Federation of AIDS-related Organizations, founded the National Association of People With AIDS and testified in front of Congressional subcommittees.[37] Campbell told the crowd that he had hugged his boyfriend on the cover of Newsweek, and then kissed Hilliard on stage, "to show Middle America that gay love is beautiful," criticising the Christian right for using scripture to justify their homophobia.[37] After criticising the lack of progress being made by the Reagan administration, he held 15 seconds of silence for the 2,000 who had died of AIDS at that point "and [for] those who will die before this is over," before laying out a series of concerns for politicians to address — including increased funding for both research and support services and a warning of the potential for discrimination with the advent of a test for HTLV-3 (now known as HIV) — and appealing to all candidates in the upcoming elections to meet with People With AIDS.[37]

Two weeks later, Campbell appeared on CBS Evening News in a live satellite interview with Dan Rather.[2] While the rumors and fear of AIDS had reached a mainstream audience, the facts had not yet, so Campbell was placed in a glass booth, with technicians refusing to come near him to wire up microphones for the interview.[2]

Death and legacy

A few days after the DNC speech, another case of shingles left scars across his head;[38] within weeks he was hospitalized with cryptosporidiosis[7][20] causing cryptococcal meningitis.[38] At noon on August 15, 1984,[38] exactly a month after his DNC speech and after 2 days on life support in intensive care,[20] Campbell died at San Francisco General Hospital[38] when his blood pressure dropped rapidly.[38] His parents and his partner Bobby Hilliard were by his side.[38] Campbell was 32 years old[38] and had lived for over 3½ with what was, by then, called AIDS.

Two days later, Castro Street was closed as 1,000 people turned out to mourn Campbell and celebrate his life.[8][38] A "reverential chant" by the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence was followed by several speeches, including Dr Conant and Hilliard as well as Campbell's parents and local performers (including Lea DeLaria and Holly Near)[38] and an audio recording of Paul Boneberg introducing Campbell at the National March for Lesbian and Gay Rights a month earlier.[8] The Gay Life radio show on KSAN-FM, presented by Randy Alfred, Campbell's editor at the Sentinel, covered his memorial across two weeks, on September 16 and 23, 1984.[39] His body was taken back to Washington state and interred at New Tacoma Cemetery in Tacoma. Campbell had kept a journal throughout his life; Angie Lewis arranged for the journal to be donated to the UCSF Archives and Special Collections[40]

The 1985 Lesbian/Gay Freedom Day Parade was dedicated to Campbell,[2][9][41] "for the work he did as a Person With AIDS, and as a symbol for all of us who continue to fight against the threat that AIDS poses to our survival."[41]

In the 1993 docudrama TV movie And the Band Played On, adapted from Randy Shilts's book of the same name about the early days of the AIDS crisis, Campbell was played by Donal Logue.[42] Campbell will also be portrayed in the 2017 docudrama miniseries When We Rise written by Dustin Lance Black to chronicle the gay rights movement, where he will be played by Kevin McHale.[42][43]

The name "Bobbi Campbell" and the names of several other key figures of the time were featured in the American Mock Trial Association's 2007–08 National Case Problem.[44] The fictional case, unrelated to Campbell's life, was used by over 300 colleges and universities throughout the United States and was dedicated to the social and scientific pioneers in the fight against HIV/AIDS.

In 2015, the group "Let’s Kick ASS—AIDS Survivor Syndrome" were looking to have a commemorative plaque erected at the site of the Star Pharmacy (now a Walgreens), where Campbell first put up images of his KS lesions.[18]

As of 2016, Bobbi Campbell is memorialized on 4 separate panels of the NAMES Project AIDS Memorial Quilt.[45]

References

- 1 2 "Robert Boyle Campbell". California Death Index, 1940–1997. November 26, 2014. Retrieved November 17, 2016 – via FamilySearch.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Alexander Inglis (February 25, 2004). "The Exhumation of Bobbi Campbell (28 Jan 1952 – 15 Aug 1984)". Blogger. Archived from the original on November 14, 2016. Retrieved November 13, 2016.

- 1 2 Lawrence K. Altman (July 3, 1981). "Rare cancer seen in 41 homosexuals". The New York Times. Retrieved July 19, 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 Michael Callan & Dan Turner (1988). "A History of the PWA Self-Empowerment Movement". In Michael Callan. Surviving and Thriving With AIDS: Collected Wisdom, Volume 2. New York City: People With AIDS Coalition. pp. 288–293. Archived from the original on January 9, 2015. Retrieved November 16, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Berkowitz, Richard (February 1997). "The Way We War". POZ. Archived from the original on June 16, 2002. Retrieved November 28, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Raymond A. Smith; Patricia D. Siplon (2006). Drugs Into Bodies: Global AIDS Treatment Activism. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 16–18. ISBN 978-0-2759-8325-3. Retrieved November 12, 2016.

- 1 2 3 Randy Shilts (November 3, 2011). And the Band Played On: Politics, People and the AIDS Epidemic. Souvenir Press. p. 575. ISBN 978-0-2856-4076-4.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Allen White (August 23, 1984). "Candles and Tears on Castro: 1,000 Mourn Bobbi Campbell". Bay Area Reporter. Retrieved November 14, 2016. Via the Online Searchable Obituary Database of the GLBT Historical Society

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Randy Shilts (November 3, 2011). And the Band Played On: Politics, People and the AIDS Epidemic. Souvenir Press. pp. 138–39. ISBN 978-0-2856-4076-4.

- ↑ Gary Atkins (2003). Gay Seattle: Stories of Exile and Belonging. University of Washington Press. p. 299. ISBN 978-0-2959-8298-4.

- ↑ Gary Atkins (2003). Gay Seattle: Stories of Exile and Belonging. University of Washington Press. p. 374. ISBN 978-0-2959-8298-4.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Joe Wright (2013). "Only Your Calamity: The Beginnings of Activism by and for People With AIDS"

. American Journal of Public Health. 103 (10): 1788–98. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2013.301381

. American Journal of Public Health. 103 (10): 1788–98. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2013.301381 . PMC 3780739

. PMC 3780739 .

. - 1 2 Bobbi Campbell (December 10, 1981). "I Will Survive! Nurse's Own 'Gay Cancer' Story". San Francisco Sentinel. Cited in Wright (2013), Am J Pub Health.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 David Hunt (June 19, 1983). I Will Survive (MP3) (Radio broadcast). Los Angeles: Pacifica Radio KPFK 90.7 FM. Archived from the original on November 16, 2016. Retrieved November 16, 2016. Audio embedded in: Colin Clews (August 4, 2014). "1983. HIV/AIDS: Pacifica Radio Programme, 'I Will Survive'". Gay in the 80s. Archived from the original on September 19, 2015. Retrieved November 16, 2016.

- ↑ "Kaposi's sarcoma and Pneumocycstis pneumonia among homosexual men – New York City and California". Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Centers for Disease Control. 30 (25): 305–308. July 4, 1981. PMID 6789108. Retrieved October 23, 2013.

- 1 2 3 David France (December 1, 2016). How to Survive a Plague: The Story of How Activists and Scientists Tamed AIDS. Pan Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-5098-3941-4. Retrieved November 14, 2016.

- ↑ Interview with Helen Schietinger, nurse coordinator of UCSF's first AIDS clinic, on January 30, 1995, by Sally Smith Hughes — in The AIDS Epidemic in San Francisco: The Response of the Nursing Profession, 1981–1984, volume I. The San Francisco AIDS Oral History Series. Regional Oral History Office, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley. 1999. p. 105.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Tez Anderson (June 17, 2015). "Walgreens HIV/AIDS Castro Spirit Historical Plaque". Let’s Kick ASS—AIDS Survivor Syndrome. Archived from the original on June 18, 2015. Retrieved November 15, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 John-Manuel Andriote (June 1, 1999). Victory Deferred: How AIDS Changed Gay Life in America. University of Chicago Press. pp. 170–72. ISBN 978-0-2260-2049-5.

- 1 2 3 Brian Jones (August 16, 1984). "Bobbi Campbell's Long Fight Ends". Bay Area Reporter. Retrieved November 14, 2016. Via the Online Searchable Obituary Database of the GLBT Historical Society

- ↑ The GLBT Historical Society's "Gayback Machine" search does not produce persistent URLs, but searching for "Bobbi Campbell" in 1981 will bring up the appropriate episode, dated 1982-01-10 and captioned "Marcus Conant, M.D. and Paul Volberding, M.D., U.C. San Francisco Medical School; Bobbi Campbell, Kaposi's Sarcoma cancer patient." It is also available offline as Reel 118, Box 16 from Randy Alfred subject files and sound recordings, collection 1991-24, GLBT Historical Society.

- 1 2 Interview with Helen Schietinger, nurse coordinator of UCSF's first AIDS clinic, on January 30, 1995, by Sally Smith Hughes — in The AIDS Epidemic in San Francisco: The Response of the Nursing Profession, 1981–1984, volume I. The San Francisco AIDS Oral History Series. Regional Oral History Office, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley. 1999. p. 147.

- ↑ Interview with Michael Helquist, journalist of the early AIDS epidemic in San Francisco, on March 24, 1995, by Sally Smith Hughes — in The AIDS Epidemic in San Francisco: The Response of the Nursing Profession, 1981–1984, volume I. Regional Oral History Office, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley. 1999. p. 30.

- 1 2 Interview with Helen Schietinger, nurse coordinator of UCSF's first AIDS clinic, on January 30, 1995, by Sally Smith Hughes — in The AIDS Epidemic in San Francisco: The Response of the Nursing Profession, 1981–1984, volume I. The San Francisco AIDS Oral History Series. Regional Oral History Office, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley. 1999. pp. 153–5.

- ↑ Those in attendance included:

- From San Francisco: Bobbi Campbell, Dan Turner (1948–90), Bobby Reynolds (died 1987) and Michael Helquist representing his recently-deceased partner Mark Feldman

- From New York City: Phil Lanzaratta (died 1986), Michael Callan (1955–93), Richard Berkowitz, Artie Felson, Bill Burke, Bob Cecchi (1942–91), Matthew Sarner M.S.W., Tom Nasrallah

- From Los Angeles: Gar Traynor

- ↑ Michael Callan; Richard Berkowitz; Richard Dworkin. "We Know Who We Are: Two Gay Men Declare War on Promiscuity". New York Native (Issue 50, November 8–21, 1982). Retrieved November 17, 2016. Linked from Richard Berkowitz (June 29, 2010). "My Safe Sex Writing 1982–2010". Retrieved November 17, 2016.

- ↑ David Paternotte; Manon Tremblay (3 March 2016). The Ashgate Research Companion to Lesbian and Gay Activism. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-3170-4290-7.

- ↑ "2000 Honoring with Pride: Joseph Sonnabend, M.D". amfAR, The Foundation for AIDS Research. 2000. Retrieved 26 July 2014.

- ↑ Barry Petersen (June 12, 1982). Early CBS Report on AIDS. CBS News. Retrieved June 17, 2016 – via YouTube.

- 1 2 Rob Frydlewicz (August 2, 2012). "Newsweek Puts a Human Face on AIDS (August 2, 1983)". ZeitGAYst: A Look at History thru Pink-Colored Glasses. TypePad. Archived from the original on October 19, 2012. Retrieved November 16, 2016.

- 1 2 3 Polina Ilieva (July 17, 2013). "Preserving History of HIV/AIDS Epidemic". Brought to Light: Stories from UCSF Archives & Special Collections. UCSF Archives and Special Collections. Retrieved November 16, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 David France (December 1, 2016). How to Survive a Plague: The Story of How Activists and Scientists Tamed AIDS. Pan Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-5098-3941-4. Retrieved November 14, 2016.

- ↑ Cynthia Gorney (October 23, 1985). "Dan White and His City's Tragedy". The Washington Post. Retrieved November 14, 2016.

- ↑ Susan Goldfarb (December 31, 1983). "Officials fear for paroled assassin's life". United Press International. Retrieved November 14, 2016.

- ↑ Allan Jalon (October 25, 1985). "Parole Agent Recalls Lonely Encino Exile of Dan White". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved November 14, 2016.

- ↑ Interview with Angie Lewis, nurse educator in the San Francisco AIDS epidemic, on June 29, 1995, by Sally Smith Hughes — in The AIDS Epidemic in San Francisco: The Response of the Nursing Profession, 1981–1984, volume II. The San Francisco AIDS Oral History Series. Regional Oral History Office, The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley. 1999. pp. 135–36.

- 1 2 3 4 Bobbi Campbell speech (1984). GLBT Historical Society. July 15, 1984. Retrieved July 19, 2015 – via YouTube.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 David France (December 1, 2016). How to Survive a Plague: The Story of How Activists and Scientists Tamed AIDS. Pan Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-5098-3941-4. Retrieved November 14, 2016.

- ↑ "Reel 247, Box 23 (The Gay Life September 16, 1984) and Reel 248, Box 23 (The Gay Life September 23, 1984)". Randy Alfred subject files and sound recordings (collection 1991-24). GLBT Historical Society.

- ↑ Julia Bazar (2007). "Finding Aid to the Angie Lewis Papers, 1980–1991 (MSS 96-31)". UCSF Archives and Special Collections. Retrieved November 17, 2016.

- 1 2 "San Francisco Pride Guide Dedication". Retrieved November 14, 2016 – via Jennah Feeley on Flickr.

- 1 2 Bobbi Campbell at the Internet Movie Database

- ↑ Lesley Goldberg (April 26, 2016). "ABC's gay rights mini enlists Michael K. Williams, sets all-star guest cast". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved November 15, 2016.

- ↑ "Past Case Materials". American Mock Trial Association. Retrieved November 18, 2016.

- ↑ "Search the quilt". NAMES Project AIDS Memorial Quilt. Retrieved November 14, 2016.

External links

- Bobbi Campbell at Find a Grave

- Finding Aid to the Bobbi Campbell Diary, 1983–1984 (MSS 96-33) — Bobbi Campbell's diaries are in the UCSF Archives and Special Collections

- Historical marker: 1981: Bobbi Campbell, RN, posts first notice about "gay cancer" on Star Pharmacy's window at 468 Castro Street, later identified as AIDS, the pandemic devastates the Castro. Campbell becomes a leading activist in the fight against the disease.'