Randy Shilts

| Randy Shilts | |

|---|---|

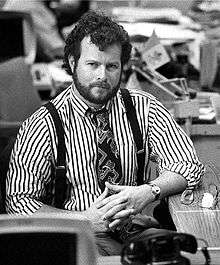

Shilts in the newsroom of the San Francisco Chronicle, 1987 | |

| Born |

August 8, 1951 Davenport, Iowa, USA |

| Died |

February 17, 1994 (aged 42) Guerneville, California, USA |

| Occupation | Journalist, author |

| Alma mater | University of Oregon |

| Genre | Journalism, history, biography |

| Literary movement | Literary journalism |

| Partner | Barry Barbieri |

Randy Shilts (August 8, 1951 – February 17, 1994) was a pioneering gay American journalist and author. He worked as a freelance reporter for both The Advocate and the San Francisco Chronicle, as well as for San Francisco Bay Area television stations.

Early life

Born August 8, 1951, in Davenport, Iowa, Shilts grew up in Aurora, Illinois, with five brothers in a politically conservative, working-class family. He majored in journalism at the University of Oregon, where he worked on the student newspaper, the Oregon Daily Emerald, becoming an award-winning managing editor. During his college days, he came out publicly as a gay man at age 20, and ran for student office with the slogan "Come out for Shilts."[1]

Journalism

Shilts graduated near the top of his class in 1975, but as an openly gay man, he struggled to find full-time employment in what he characterized as the homophobic environment of newspapers and television stations at that time.[1] After several years of freelance journalism, he was finally hired as a national correspondent by the San Francisco Chronicle in 1981, becoming "the first openly gay reporter with a gay 'beat' in the American mainstream press."[2] AIDS, the disease that would later take his life, first came to nationwide attention that same year and soon Shilts devoted himself to covering the unfolding story of the disease and its medical, social, and political ramifications.

Books

In addition to his extensive journalism, Shilts wrote three best-selling, widely acclaimed books. His first book, The Mayor of Castro Street: The Life and Times of Harvey Milk, is a biography of openly gay San Francisco politician Harvey Milk, who was assassinated by a political rival, Dan White, in 1978. The book broke new ground, being written at a time when "the very idea of a gay political biography was brand-new."[2]

Shilts's second book, And the Band Played On: Politics, People, and the AIDS Epidemic, published in 1987, won the Stonewall Book Award and brought him nationwide literary fame. And the Band Played On is an extensively researched account of the early days of the AIDS epidemic in the United States. The book was translated into seven languages,[3] and was later made into an HBO film of the same name in 1993, with many big-name actors in starring or supporting roles, including Matthew Modine, Richard Gere, Anjelica Huston, Phil Collins, Lily Tomlin, Ian McKellen, Steve Martin, and Alan Alda, among others. The film earned 20 nominations and nine awards, including the 1994 Emmy Award for Outstanding Made for Television Movie.[4]

His last book, Conduct Unbecoming: Gays and Lesbians in the US Military from Vietnam to the Persian Gulf, which examined discrimination against lesbians and gays in the military, was published in 1993. Shilts and his assistants conducted over a thousand interviews while researching the book, the last chapter of which Shilts dictated from his hospital bed.[5]

Shilts's writing was admired for its powerful narrative drive, interweaving personal stories with political and social reporting. Shilts saw himself as a literary journalist in the tradition of Truman Capote and Norman Mailer.[6] Undaunted by a lack of enthusiasm for his initial proposal for the Harvey Milk biography, Shilts reworked the concept, as he later said, after further reflection:

I read Hawaii by James Michener. That gave me the concept for the book, the idea of taking people and using them as vehicles, symbols for different ideas. I would take the life-and-times approach and tell the whole story of the gay movement in this way, using Harvey as the major vehicle.[6]

Criticism and praise

Although Shilts was applauded for bringing public attention to bear on gay civil-rights issues and the AIDS crisis, he was also harshly criticized (and spat upon on Castro Street) by some in the gay community for calling for the closure of gay bathhouses in San Francisco to slow the spread of AIDS.[7] Shilts maintained his sense of integrity in spite of being called "a traitor to his own kind" by a fellow Bay Area journalist.[1] In a note included in The Life and Times of Harvey Milk, Shilts expressed his view of a reporter's duty to rise above criticism:

I can only answer that I tried to tell the truth and, if not be objective, at least be fair; history is not served when reporters prize trepidation and propriety over the robust journalistic duty to tell the whole story.[7]

Shilts was also criticized by some segments of the gay community on other issues, including his opposition to the controversial practice of outing prominent but closeted lesbians and gay men.

Nevertheless, his tenacious reporting was highly praised by others in both the gay and straight communities who saw him as "the pre-eminent chronicler of gay life and spokesman on gay issues".[5] Shilts was honored with the 1988 Outstanding Author award from the American Society of Journalists and Authors, the 1990 Mather Lectureship at Harvard University, and the 1993 Lifetime Achievement Award from the National Lesbian and Gay Journalists' Association.[3]

In 1999, the Department of Journalism at New York University ranked Shilts's AIDS reporting for the Chronicle between 1981 and 1985 as number 44 on a list of the top 100 works of journalism in the United States in the 20th century.[8]

Illness and death

Shilts declined to be told the results of his HIV test until he had completed the writing of And the Band Played On, concerned that the test result, whatever it might be, would interfere with his objectivity as a writer.[5] He was finally found to be HIV positive in March 1987. Although he took the anti-HIV drug AZT for several years, he did not publicly disclose his AIDS diagnosis until shortly before he died.

In 1992, Shilts came down with pneumocystis carinii pneumonia and suffered a collapsed lung; the following year, he came down with Kaposi's sarcoma. In a New York Times interview in the spring of 1993, Shilts observed, "HIV is certainly character-building. It's made me see all of the shallow things we cling to, like ego and vanity. Of course, I'd rather have a few more T-cells and a little less character."[5] Despite being effectively homebound and on oxygen, he was able to attend the Los Angeles screening of the HBO film version of And the Band Played On in August 1993.

Shilts died, aged 42, at his 10-acre (4 ha) ranch in Guerneville, Sonoma County, California, being survived by his partner, Barry Barbieri, his mother, and his brothers. His brother Gary had conducted a commitment service for the couple the previous year.[7] After a funeral service at Glide Memorial Church, Shilts was buried at Redwood Memorial Gardens in Guerneville.[6]

Legacy

Shilts bequeathed 170 cartons of papers, notes, and research files to the local history section of the San Francisco Public Library. At the time of his death, he was planning a fourth book, examining homosexuality in the Roman Catholic Church.[6]

As a fellow reporter put it, despite an early death, in his books Shilts "rewrote history. In doing so, he saved a segment of history from extinction."[1] Historian Garry Wills wrote of And the Band Played On, "This book will be to gay liberation what Betty Friedan was to early feminism and Rachel Carson's Silent Spring was to environmentalism."[7] NAMES Project founder Cleve Jones described Shilts as "a hero" and characterized his books as "without question the most important works of literature affecting gay people."[1]

After his death, a longtime friend and assistant explained the motivation that drove Shilts: "He chose to write about gay issues for the mainstream precisely because he wanted other people to know what it was like to be gay. If they didn't know, how were things going to change?"[1]

In 1998, Shilts was memorialized in the Hall of Achievement at the University of Oregon School of Journalism, honoring his refusal to be "boxed in by the limits that society offered him. As an out gay man, he carved a place in journalism that was not simply groundbreaking but internationally influential in changing the way the news media covered AIDS."[3] A San Francisco Chronicle reporter summed up the achievement of his late "brash and gutsy" colleague:

Perhaps because Shilts remains controversial among some gays, there is no monument to him. Nor is there a street named for him, as there are for other San Francisco writers such as Jack Kerouac and Dashiell Hammett. ... Shilts' only monument is his work. He remains the most prescient chronicler of 20th century American gay history.[1]

In 2006, the award-winning Reporter Zero, a half-hour biographical documentary about Shilts featuring interviews with friends and colleagues, was produced and directed by filmmaker Carrie Lozano.[9]

Bibliography

- Familiar Faces, Hidden Lives: The Story of Homosexual Men in America Today, by Howard J. Brown, M.D., Introduction by Randy Shilts, 1976 (ISBN 0-156-30120-2)

- The Mayor of Castro Street: The Life and Times of Harvey Milk, 1982 (ISBN 0-312-52331-9)

- And the Band Played On: Politics, People, and the AIDS Epidemic (1980–1985), 1987 (ISBN 0-613-29872-1)

- Conduct Unbecoming: Gays and Lesbians in the U.S. Military, 1993 (ISBN 0-312-34264-0)

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Randy Shilts was gutsy, brash and unforgettable"; Weiss, Mike; San Francisco Chronicle, February 17, 2004; Page D-1; Retrieved on 2007-01-03

- 1 2 Randy Shilts at Queer Theory Retrieved on 2007-01-03

- 1 2 3 School of Journalism and Communication Hall of Achievement. Retrieved on 2007-01-03

- ↑ IMDb entry for And the Band Played On. Retrieved on 2007-01-03

- 1 2 3 4 "AT HOME WITH: Randy Shilts; Writing Against Time, Valiantly"; Schmalz, Jeffrey; The New York Times, April 22, 1993 Retrieved on 2007-01-03

- 1 2 3 4 California Association of Teachers of English. California authors: Randy Shilts, 1951–1994; Albert, Janice; Retrieved on 2007-01-03

- 1 2 3 4 "Randy Shilts, Chronicler of AIDS Epidemic, Dies at 42; Journalism: Author of 'And the Band Played On' is credited with awakening nation to the health crisis"; Warren, Jennifer and Paddock, Richard; Los Angeles Times; February 18, 1994; PAGE: A-1; Retrieved on 2007-01-03

- ↑ New York University: Top 100 Works of Journalism; Project Director: Mitchell Stephens; announced March 1999; Retrieved on 2007-01-03

- ↑ Reporter Zero Official Website; Retrieved on 2007-01-03

External links

- Podcast, "AIDS at 25 – Reflections on reporter Randy Shilts," San Francisco Chronicle

- "Randy Shilts, 1951–1994," e-Notes Criticism and Essays

- LGBT Journalists Hall of Fame, National Lesbian and Gay Journalists Association at the Wayback Machine (archived September 27, 2007)

- Randy Shilts on glbtq.com

- Randy Shilts at Find a Grave