Aqueous humour

| Aqueous humor | |

|---|---|

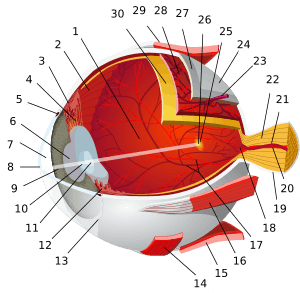

Schematic diagram of the human eye. | |

| Details | |

| Latin | humor aquosus |

The aqueous humour is a transparent, watery [1] fluid similar to plasma, but containing low protein concentrations. It is secreted from the ciliary epithelium, a structure supporting the lens.[2] It fills both the anterior and the posterior chambers of the eye, and is not to be confused with the vitreous humour, which is located in the space between the lens and the retina, also known as the posterior cavity or vitreous chamber. [3]

Structure

Composition

- Amino acids: transported by ciliary muscles

- 98% water

- Electrolytes

- Ascorbic acid

- Glutathione

- Immunoglobulins

Function

- Maintains the intraocular pressure and inflates the globe of the eye. It is this hydrostatic pressure which keeps the eyeball in a roughly spherical shape and keeps the walls of the eyeball taut.

- Provides nutrition (e.g. amino acids and glucose) for the avascular ocular tissues; posterior cornea, trabecular meshwork, lens, and anterior vitreous.

- May serve to transport ascorbate in the anterior segment to act as an antioxidant agent.

- Presence of immunoglobulins indicate a role in immune response to defend against pathogens.

- Provides inflation for expansion of the cornea and thus increased protection against dust, wind, pollen grains and some pathogens.

- for refractive index.

Production and drainage

The main eye structures related to aqueous humor dynamics are the ciliary body (the site of aqueous humor production), and the trabecular meshwork and the uveoscleral pathway (the principal locations of aqueous humor outflow).[4]

Aqueous humor is secreted into the posterior chamber by the ciliary body, specifically the non-pigmented epithelium of the ciliary body (pars plicata). It flows through the narrow cleft between the front of the lens and the back of the iris, to escape through the pupil into the anterior chamber, and then to drain out of the eye via the trabecular meshwork. From here, it drains into Schlemm's canal by one of two ways: directly, via aqueous vein to the episcleral vein, or indirectly, through collector channels to the episcleral vein by intrascleral plexus and eventually into the veins of the orbit. 5 alpha-dihydrocortisol, an enzyme inhibited by 5-alpha reductase inhibitors, may be involved in production of aqueous humor.[5]

Drainage

Aqueous humor is continually produced by the ciliary processes and this rate of production must be balanced by an equal rate of aqueous humor drainage. Small variations in the production or outflow of aqueous humour will have a large influence on the intraocular pressure.

The drainage route for aqueous humour flow is first through the posterior chamber, then the narrow space between the posterior iris and the anterior lens (contributes to small resistance), through the pupil to enter the anterior chamber. From there, the aqueous humour exits the eye through the trabecular meshwork into Schlemm's canal (a channel at the limbus, i.e., the joining point of the cornea and sclera, which encircles the cornea[6]) It flows through 25–30 collector canals into the episcleral veins. The greatest resistance to aqueous flow is provided by the trabecular meshwork (esp. the juxtacanalicular part), and this is where most of the aqueous outflow occurs. The internal wall of the canal is very delicate and allows the fluid to filter due to high pressure of the fluid within the eye.[6] The secondary route is the uveoscleral drainage, and is independent of the intraocular pressure, the aqueous flows through here, but to a lesser extent than through the trabecular meshwork (approx. 10% of the total drainage whereas by trabecular meshwork 90% of the total drainage).

The fluid is normally 15 mmHg (0.6 inHg) above atmospheric pressure, so when a syringe is injected the fluid flows easily. If the fluid is leaking, due to collapse and wilting of cornea, the hardness of the normal eye is therefore corroborated.[6]

Clinical significance

Glaucoma is a progressive optic neuropathy where retinal ganglion cells and their axons die causing a corresponding visual field defect. An important risk factor is increased intraocular pressure (pressure within the eye) either through increased production or decreased outflow of aqueous humour.[7] Increased resistance to outflow of aqueous humour may occur due to an abnormal trabecular mesh work or to obliteration of the meshwork due to injury or disease of the iris. However, increased interocular pressure is neither sufficient nor necessary for development of primary open angle glaucoma, although it is a major risk factor. Uncontrolled glaucoma typically leads to visual field loss and ultimately blindness.

Additional Images

-

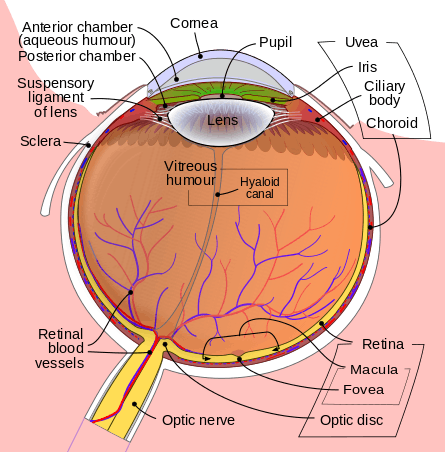

Structures of the eye labeled

-

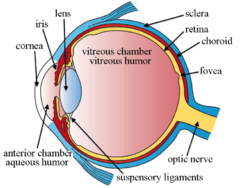

This image shows another labeled view of the structures of the eye

See also

References

- ↑ "Vitreous and Aqueous Humor".

- ↑ Human Physiology. An Integrate approach. 5th edition. Dee Unglaub Silverthorn

- ↑ "Eye Anatomy". WebMD. Retrieved 8 March 2016.

- ↑ Goel, Manik. "Aqueous Humor Dynamics: A Review~!2010-03-03~!2010-06-17~!2010-09-02~!". The Open Ophthalmology Journal. 4 (1): 52–59. doi:10.2174/1874364101004010052. PMC 3032230

. PMID 21293732.

. PMID 21293732. - ↑ Weinstein, B. I.; Kandalaft, N.; Ritch, R.; Camras, C. B.; Morris, D. J.; Latif, S. A.; Vecsei, P.; Vittek, J.; Gordon, G. G.; Southren, A. L. (1991). "5 alpha-dihydrocortisol in human aqueous humor and metabolism of cortisol by human lenses in vitro". Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 32 (7): 2130–2135. PMID 2055703.

- 1 2 3 "eye, human."Encyclopædia Britannica from Encyclopædia Britannica 2006 Ultimate Reference Suite DVD 2009

- ↑ "Glaucoma Medications: Click for Facts About Side Effects".

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Aqueous humour. |

- Anatomy diagram: 02566.000-1 at Roche Lexicon - illustrated navigator, Elsevier