Y Sap mine

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Y Sap mine was an underground explosive charge, secretly planted by the British during the First World War, ready for 1 July 1916, the first day on the Somme. The mine was dug by the tunnelling companies of the Royal Engineers under a German multiple machine gun position on the north flank of the village of La Boisselle in the Somme département. The mine was named after Y Sap, the British trench from which the gallery was driven. It was part of a series of 19 mines that were placed beneath the German lines on the British section of the Somme front to assist the start of the battle. The Y Sap mine was sprung at 7:28 a.m. on 1 July 1916 and left a large crater, but failed to assist the British attack as the Germans had detected the mine in time, relocated their machine-guns and at Zero Hour shot crossfire at the advancing British. The crater of the Y Sap mine was filled in after World War I and is no longer visible.

Background

1914

French and German military operations began on the Somme in September 1914. A German advance westwards towards Albert was stopped by the French at La Boisselle and attempts to resume offensive warfare in October failed. Both sides reduced their attacks to local operations or raids and began to fortify their remaining positions with underground works. On 18 December, the French captured the La Boisselle village cemetery at the west end of a German salient and established an advanced post only 3 metres (3.3 yd) from the German front line. By 24 December, the French had forced the Germans back from the cemetery and the western area of La Boisselle but their advance was stopped a short distance forward at L'îlot de La Boisselle, in front of German trenches protected by barbed wire.[1] Once the location of a farm and a small number of buildings, L'îlot became known as Granathof (German, shell farm) to the Germans and later as the Glory Hole to the British. On Christmas Day 1914, French engineers sank the first mine shaft at La Boisselle.[2]

1915

Fighting continued in no man's land at the west end of La Boisselle, where the opposing lines were 200 yards (180 m) apart, even during lulls along the rest of the Somme front. On the night of 8/9 March, a German sapper inadvertently broke into French mine gallery, which he found to have been charged with explosives; a group of volunteers took 45 nerve racking minutes to dismantle the charge and cut the firing cables. From April 1915 – January 1916, 61 mines were sprung around L'îlot, some loaded with 20,000–25,000 kilograms (44,000–55,000 lb) of explosives.[3]

The French mine workings were taken over when the British moved into the Somme front.[4] G.F. Fowke moved the 174th and 183rd Tunnelling Companies into the area, but at first the British did not have enough miners to take over the large number of French shafts; the problem was temporarily solved when the French agreed to leave their engineers at work for several weeks.[5] On 24 July 1915, the 174th Tunnelling Company established headquarters at Bray, taking over some 66 shafts at Carnoy, Fricourt, Maricourt and La Boisselle. No man's land just south-west of La Boisselle was very narrow, at one point about 46 metres (50 yd) wide, and had become pockmarked by many chalk craters.[6] To provide the tunnellers needed, the British formed the 178th and 179th Tunnelling Companies in August 1915, followed by the 185th and 252nd Tunnelling Companies in October.[5] The 181st Tunnelling Company was also present on the Somme.[7]

Elaborate precautions were taken to preserve secrecy, since no continuous front line trench ran through the area opposite the west end of La Boisselle and the British front line. The L'îlot site was defended by posts near the mine shafts.[4] The underground war continued with offensive mining to destroy opposing strong points and defensive mining to destroy tunnels, which were 30–120 feet (9.1–36.6 m) long. Around La Boisselle, the Germans dug defensive transverse tunnels about 80 feet (24 m) long, parallel to the front line.[6] On 19 November 1915, the 179th Tunnelling Company commander, Captain Henry Hance, estimated that the Germans were 15 yards (14 m) away and ordered the mine chamber to be loaded with 2,700 kilograms (6,000 lb) of explosives, which was completed by midnight on 20/21 November. At 1:30 a.m. the Germans blew the charge, filling the remaining British tunnels with carbon monoxide. The right and left tunnels collapsed and it was later found that the German explosion had detonated the British charge.[8][lower-alpha 1]

Prelude

1916

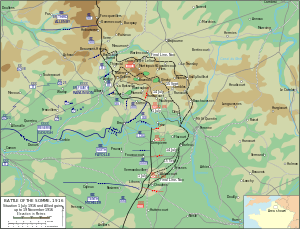

At the start of the Battle of Albert (1–13 July), the name given by the British to the first two weeks of the Battle of the Somme, La Boisselle stood on the main axis of British attack. The tunnelling companies were to make two major contributions to the Allied preparations for the battle by placing 19 large and small mines beneath the German positions along the front line and by preparing a series of shallow Russian saps from the British front line into no man's land, which would be opened at Zero Hour and allow the infantry to attack the German positions from a comparatively short distance.[9]

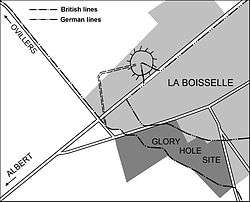

At La Boisselle, four mines were prepared by the Royal Engineers: Two charges (known as No 2 straight and No 5 right) were planted at L'îlot at the end of galleries dug from Inch Street Trench by the 179th Tunnelling Company, intended to wreck German tunnels and create crater lips to block enfilade fire along no man's land.[10] As the Germans in La Boisselle had fortified the cellars of ruined houses, and cratered ground made a direct infantry assault on the village impossible, two further mines, known as Y Sap and Lochnagar after the trenches from which they were dug, were laid on the north-east and the south-east of La Boisselle to assist the attack on either side of the German salient in the village[8][6] – see map.

The 185th Tunnelling Company started work on the Lochnagar mine on 11 November 1915 and handed the tunnels over to 179th Tunnelling Company in March 1916.[6] A month before the handover, 18 men of the 185th Tunnelling Company (2 officers, 16 sappers) were killed on 4 February when the Germans detonated a camouflet near the British three-level mine system, starting from Inch Street, La Boisselle, the deepest level being just above the water table at around 30 metres (100 ft).[6]

The Sap mine underneath the German trenches overlooking Mash Valley[11] just north of La Boisselle consisted of one mine chamber with a single access tunnel (see map). The tunnel started in the British front line near where it crossed the D 929 Albert–Bapaume road, but because of German underground defences the galllery could not be dug in a straight line. About 460 metres (500 yd) were dug into no man's land, before it turned right for about another 460 metres (500 yd). About 18,000 kilograms (40,000 lb) of ammonal was placed in the chamber beneath the Y Sap mine.[6] For silence, the tunnellers used bayonets with spliced handles and worked barefoot on a floor covered with sandbags. Flints were carefully prised out of the chalk and laid on the floor; if the bayonet was manipulated two-handed, an assistant caught the dislodged material. Spoil was placed in sandbags and passed hand-by-hand, along a row of miners sitting on the floor and stored along the side of the tunnel, later to be used to tamp the charge.[12] The Lochnagar and the Y Sap mines were "overcharged" to ensure that large rims were formed from the disturbed ground.[6] Communication tunnels were also dug for use immediately after the first attack.[6] The mines were laid without interference by German miners but as the explosives were placed, German miners could be heard below Lochnagar and above the Y Sap mine.[12]

179th Tunnelling Company's commander, Captain Henry Hance, recommended to blow the Y Sap mine several days early so it would wipe out the German machine-gun post on the northern edge of La Boisselle and so cut out the German chance of enfilade. The resulting crater could then be occupied by the British infantry and used by the Royal Engineers to dig an advanced jumping-off trench for the British infantry, a trench that would effectively reduce the distance the British would have to cross over no man's land by over 150 metres (160 yd). Hance's superiors agreed that firing the Y Sap mine early could help to neutralise enemy fire from the flanks around La Boisselle, but at the same time, the explosion would warn the Germans that a British attack was imminent. Hance's advice was dismissed.[13]

Battle

1 July

The four mines at La Boisselle were detonated at 7:28 a.m. on 1 July 1916, the first day on the Somme.[6] At the time, the Y Sap and Lochnagar mines were the largest mines ever detonated.[14] The blast was, at that time, the largest sound made by man, some reports said that it could be heard from London.[15] They would be surpassed a year later by the mines in the Battle of Messines. The explosion of the Y Sap mine left a large crater, but failed to assist the British attack at Zero Hour as the Germans had detected the mine in time and evacuated their position. After relocating their machine-guns, the Germans shot crossfire at the advancing British from their new position, particularly at the 102nd (Tyneside Scottish) Brigade (Brigadier-General T. P. B. Tiernan), which made up the left flank of the 34th Division's attack on La Boisselle.[16] The brigade suffered the worst losses of any brigade on the first day on the Somme; there were heavy casualties even before its battalions reached the British front-line. Its losses on 1 July were so severe that on 6 July, the brigade was transferred to the 37th Division.

Aerial observation

The blowing of the Y Sap and Lochnagar mines was witnessed by pilots who were flying over the battlefield to report back on British troop movements. It had been arranged that continuous patrols would fly throughout the day. 2nd Lieutenant Cecil Lewis' patrol of 3 Squadron was warned against flying too close to La Boisselle, where two mines were due to go up but would be able to watch from a safe distance. Flying up and down the line in a Morane Parasol, he watched from above Thiepval, almost two miles from La Boisselle, and later described the early morning scene in his book Sagittarius Rising (1936):

We were over Thiepval and turned south to watch the mines. As we sailed down above all, came the final moment. Zero! At Boisselle the earth heaved and flashed, a tremendous and magnificent column rose up into the sky. There was an ear-splitting roar, drowning all the guns, flinging the machine sideways in the repercussing air. The earthly column rose, higher and higher to almost four thousand feet. There it hung, or seemed to hang, for a moment in the air, like a silhouette of some great cypress tree, then fell away in a widening cone of dust and debris. A moment later came the second mine. Again the roar, the upflung machine, the strange gaunt silhouette invading the sky. Then the dust cleared and we saw the two white eyes of the craters. The barrage had lifted to the second-line trenches, the infantry were over the top, the attack had begun.

Analysis

Despite their colossal size, the Y Sap and Lochnagar mines failed to help sufficiently neutralise the German defences in La Boisselle. The ruined village was meant to fall in 20 minutes but by the end of the first day of the battle, it had not been taken while the III Corps divisions had lost more than 11,000 casualties. At Mash Valley, the attackers lost 5,100 men before noon, and at Sausage Valley near the crater of the Lochnagar mine, there were over 6,000 casualties – the highest concentration on the entire battlefield. The 34th Division, in III Corps, suffered the worst losses of any unit that day.[8]

Fate

After the Armistice of 11 November 1918, the former inhabitants of La Boisselle returned and rebuilt their houses. The site of the Y Sap mine crater was filled in, landscaped and partly built over. It is no longer visible today.[20][21]

See also

Notes

Footnotes

- ↑ Whitehead 2010, pp. 159–174.

- ↑ "La Boisselle Study Group". www.laboisselleproject.com. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

- ↑ Sheldon 2005, pp. 62–65.

- 1 2 Edmonds 1932, pp. 38, 371.

- 1 2 Jones 2010, p. 114.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Dunning 2015.

- ↑ Fenwick 2008.

- 1 2 3 4 Banning 2011.

- ↑ Jones 2010, p. 115.

- ↑ Shakespear 1921, p. 37.

- ↑ Gilbert 2007, pp. 51.

- 1 2 Edmonds 1932, p. 375.

- ↑ Jones 2010, pp. 124–125.

- ↑ Legg 2013.

- ↑ Waugh 2014.

- ↑ Edmonds 1932, pp. 375–376.

- ↑ Lewis 1936, p. 90.

- ↑ Gilbert 2007, p. 54.

- ↑ "Statistics". www.lochnagarcrater.org. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

- ↑ "Webmatters : Battle of the Somme: Ovillers and La Boisselle, 1st July 1916". www.webmatters.net. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

- ↑ "Y Sap Mine, La Boiselle". www.mikemccormac.com. Retrieved 3 December 2016.

Bibliography

Books

- Edmonds, J. E. (1993) [1932]. Military Operations France and Belgium, 1916: Sir Douglas Haig's Command to the 1st July: Battle of the Somme. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. I (Imperial War Museum and Battery Press ed.). London: Macmillan. ISBN 0-89839-185-7.

- Gilbert, M. (2007). Somme: The Heroism and Horror of War. London: John Murray. ISBN 978-0-7195-6890-9.

- Jones, Simon (2010). Underground Warfare 1914-1918. Barnsley: Pen & Sword Books. ISBN 978-1-84415-962-8.

- Lewis, C. A. (1977) [1936]. Sagittarius Rising: The Classic Account of Fying in the First World War (2nd Penguin ed.). London: Peter Davis. ISBN 0-14-00-4367-5. OCLC 473683742.

- Shakespear, J. (2001) [1921]. The Thirty-Fourth Division, 1915–1919: The Story of its Career from Ripon to the Rhine (Naval & Military Press ed.). London: H. F. & G. Witherby. ISBN 1-84342-050-3. OCLC 6148340. Retrieved 18 October 2014.

- Sheldon, J. (2006) [2005]. The German Army on the Somme 1914–1916 (Pen & Sword Military ed.). London: Leo Cooper. ISBN 1-84415-269-3.

- Whitehead, R. J. (2013) [2010]. The Other Side of the Wire: The Battle of the Somme. With the German XIV Reserve Corps, September 1914 – June 1916. I (paperback reprint ed.). Solihull: Helion. ISBN 978-1-908916-89-1.

Websites

- Banning, J. (2011). "Tunnellers". La Boisselle Study Group. et al. Retrieved 26 June 2015.

- Dunning, R. (2015). "Military Mining". Lochnagar Crater. Retrieved 26 June 2015.

- Fenwick, S. C. (4 December 2008). "Corps History: Part 14 The Corps and the First World War (1914–18)". Royal Engineers Museum and Library. Retrieved 10 November 2016.

- Legg, J. "Lochnagar Mine Crater Memorial, La Boisselle, Somme Battlefields". www.greatwar.co.uk. Retrieved 18 May 2013.

- Waugh, I. (2014). "WW1 Trip to the Somme". Old British News. Retrieved 19 October 2014.

Further reading

- Gliddon, G. (1987). When the Barrage Lifts: A Topographical History and Commentary on the Battle of the Somme 1916. Norwich: Gliddon Books. ISBN 0-947893-02-4.

- Jones, H. A. (2002) [1928]. The War in the Air, Being the Story of the Part Played in the Great War by the Royal Air Force (PDF). II (Imperial War Museum and Naval & Military Press ed.). London: Clarendon Press. ISBN 1-84342-413-4. Retrieved 18 October 2014.

- Masefield, J. (1917). The Old Front Line (PDF). New York: Macmillan. OCLC 869145562. Retrieved 19 October 2014.

- Middlebrook, M. (1971). The First Day on the Somme. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-139071-9.

- Skinner, J. (2012). Writing the Dark Side of Travel. New York: Berghahn Books. ISBN 978-0-85745-341-9. Retrieved 19 October 2014.

- Whitehead, R. J. (2013). The Other Side of the Wire: The Battle of the Somme. With the German XIV Reserve Corps, 1 July 1916. II. Solihull: Helion. ISBN 978-1-907677-12-0.

- Wyrall, E. (2009) [1932]. The Nineteenth Division 1914–1918 (Naval & Military Press ed.). London: Edward Arnold. ISBN 1-84342-208-5.

External links

- Aerial view with front lines; the site of the Y Sap mine is visible in the back

- La Boisselle Study Group

- Ovillers-La-Boisselle photo essay