Battle of Neuve Chapelle

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The Battle of Neuve Chapelle (10–13 March 1915) took place in the First World War. It was a British offensive in the Artois region of France and broke through at Neuve-Chapelle but the success could not be exploited. More troops had arrived from Britain and relieved some French troops in Flanders, which enabled a continuous British line to be formed, from Givenchy-lès-la-Bassée north to Langemarck. The battle was intended to cause a rupture in the German lines, which would then be exploited with a rush to the Aubers Ridge and possibly Lille. A French assault at Vimy Ridge on the Artois plateau was also planned, to threaten the road, rail and canal junctions at La Bassée from the south, as the British attacked from the north.

If the French Tenth Army captured Vimy Ridge and the north end of the Artois plateau, from Lens to La Bassée, as the British First Army took Aubers Ridge from La Bassée to Lille, a further advance of 10–15 miles (16–24 km) would cut the roads and railways used by the Germans, to supply the troops in the Noyon Salient from Arras south to Rheims. The French part of the offensive was cancelled, when the British were unable to relieve the French IX Corps north of Ypres, which had been intended to move south for the French attack and the Tenth Army contribution was reduced to support from its heavy artillery.

The Royal Flying Corps (RFC) carried out aerial photography despite poor weather, which enabled the attack front to be mapped to a depth of 1,500 yards (1,400 m) for the first time and for 1,500 copies of 1:5,000 scale maps to be distributed to each corps. The battle was the first deliberately planned British offensive and showed the form which position warfare took for the rest of the war on the Western Front. Tactical surprise and a break-through were achieved, after the First Army prepared the attack with great attention to detail. After the first set-piece attack, unexpected delays slowed the tempo of operations, command was undermined by communication failures and infantry-artillery co-operation broke down, when the telephone system failed and the Germans had time to receive reinforcements and dig a new line.

The British attempted to renew the advance, by attacking where the original assault had failed, instead of reinforcing success and a fresh attack with the same detailed preparation as that on the first day became necessary. A big German counter-attack by twenty infantry battalions (c. 16,000 men) early on 12 March, was a costly failure. Douglas Haig, the First Army commander, cancelled further attacks and ordered the captured ground to be consolidated, preparatory to a new attack further north. An acute shortage of artillery ammunition made a new attack impossible, apart from a local effort by the 7th Division, which was another costly failure. The Germans strengthened the defences opposite the British and increased the number of troops in the area; the French became cautiously optimistic that British forces could be reliable in offensive operations.

Battle

| Gun type | No | shells | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 13-pdr | 60 | 600 | |

| 18-pdr | 324 | 410 | |

| 4.5-inch how | 54 | 212 | |

| 60-pdr | 12 | 450 | |

| 4.7-inch gun | 32 | 437 | |

| 6-inch how | 28 | 285 | |

| 6-inch gun | 4 | 400 | |

| 9.2-inch how | 3 | 333 | |

| 2.75-inch gun | 12 | 500 | |

| 15-inch how | 1 | 40 | |

Despite poor weather conditions, the early stages of the battle went extremely well for the British. The RFC quickly secured aerial dominance and set about bombarding railways and German reserves en route.[2] At 7:30 a.m. on 10 March, the British began a thirty-five-minute artillery bombardment by 90 × 18-pdr field guns of the Indian Corps and the IV Corps, on the German wire which was destroyed within ten minutes. The remaining fifteen 18-pdr batteries, six 6-inch howitzer siege batteries and six QF 4.5-inch howitzer batteries with sixty howitzers fired on the German front-line trenches. The trenches were 3 feet (0.91 m) deep, with breastworks 4 feet (1.2 m) high but were unable to withstand a howitzer bombardment. The bombardment was followed by an infantry assault at 8:05 a.m.[3]

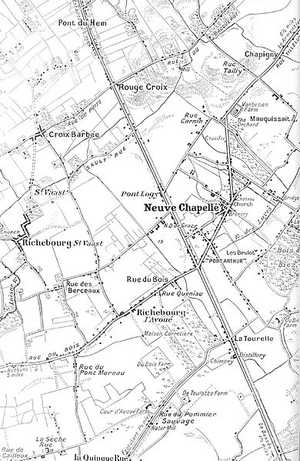

The Garhwal Brigade of the Meerut Division, Indian Corps attacked with all four battalions on a 600 yards (550 m) front, from Port Arthur to Pont Logy. On the right the attack quickly collapsed, both companies losing direction and veering to the right. The attack confronted a part of the German defence not bombarded by the artillery and before the mistake was realised the two support companies followed suit. The Indian troops forced their way through the German wire and took 200 yards (180 m) of the German front trench, despite many casualties. The three Garhwal battalions to the left advanced in lines of platoon fifty paces apart, swiftly crossing the 200 yards (180 m) of no man's land and overran the German infantry, they subsequently pressed on to the German support trench, the attack taking only fifteen minutes to complete. The leading companies then advanced beyond the Port Arthur–Neuve Chapelle road, without waiting for the planned thirty-minute artillery preparation and took the village by 9:00 a.m. along with 200 prisoners and five machine-guns.[4]

A gap of 250 yards (230 m) had been created by the loss of direction on the right, where the German garrison had been severely bombarded, but the survivors, about two platoons of the 10th Company, Infantry Regiment 16 fought on. A fresh British attack was arranged from the north, in which the Garhwali troops were to join in with a frontal assault. German troops infiltrated northwards, before being forced back by bombers and bayonet charges but the Indian attack was stopped by the Germans, 200 yards (180 m) south of the Port Arthur–Neuve Chapelle road.[5] Haig ordered more attacks that day, with similarly disappointing results.[4]

The German defences in the centre were quickly overrun on a 1,600 yards (1,500 m) front and Neuve Chapelle was captured by 10:00 a.m.[6] At Haig's request, the British Commander-in-Chief Field Marshal Sir John French, the British commander in France, released the 5th Cavalry Brigade to exploit the expected breakthrough.[7] On the left of the attack, two companies of the German Jäger Battalion 11 (with c. 200 men and a machine-gun) delayed the advance for more than six hours until forced to retreat, which stopped the advance.[8] Although aerial photography had been useful, it was unable to efficiently identify the enemy's strong defensive points. Primitive communications also meant that the British commanders had been unable to keep in touch with each other and the battle thus became uncoordinated and this in turn disrupted the supply lines.[7] On 12 March, German forces commanded by Crown Prince Rupprecht, launched a counter-attack which failed but forced the British to use most of their artillery ammunition and the British offensive was postponed on 13 March and abandoned two days later.[9]

Aftermath

Analysis

The battle at Neuve Chapelle marked a watershed in trench warfare, which showed how the new conditions affected attack and defence. A break-through in trench defences was possible if the attack was carefully prepared and disguised to achieve at least local surprise but after the initial shock the German defence recovered as the attackers were beset by delays, loss of communication and consequent disorganisation. By the end of March Major-General Du Cane had written a report that the First Army command system disintegrated after the village was captured and that although Haig had made his intent plain to his subordinates, they had not grasped the "spirit" of the plan and had failed to press on when initial objectives had been captured, although one of the subordinate commanders later claimed that pressing on would have backfired due to the lack of ammunition.[10]

The British telephone system proved vulnerable to German artillery-fire and the movement of troops along communication trenches was delayed by far more than the most pessimistic expectations. An equilibrium between attack and defence quickly resumed, which could only be upset by another set-piece attack, after a delay for preparation which gave the defenders just as much time to reorganise. The attack front was found to have been wide enough to make it impossible for the small number of German reserves to defeat the attack but the attackers had not been ordered to assist units which had been held up and reinforcements were sent to renew failed attacks rather than reinforce success. Small numbers of German troops in strong-points and isolated trenches, had been able to maintain a volume of small-arms fire sufficient to stop the advance of far greater numbers of attackers.[11]

The battle had no strategic effect but showed that the British were capable of mounting an organised attack, after several winter months of static warfare. They recaptured about 2 km (1.2 mi) of ground. In 1961 Alan Clark wrote that relations with the French improved, because British commanders had shown themselves willing to order attacks regardless of loss and quoted Brigadier-General John Charteris that

... England will have to accustom herself to far greater losses than those of Neuve Chapelle before we finally crush the German army."— Charteris[12]

Cassar called the battle a British tactical success but that the strategic intentions had not been met.[13] Sheldon was less complimentary and wrote that although the attack had shocked the German army, it quickly amended its defensive tactics and that the British had also been shocked, that such a carefully planned attack had collapsed after the first day. Sheldon called the British analysis of the battle "bluster" and wrote that Joseph Joffre, the French commander, praised the results of the first day, then dismissed the significance of the attack "Mais ce fut un succès sans lendemain" (But it was a success which led to nothing.)[14] The German and French armies began to revise their low opinion of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF), the Germans having assumed that the British would remain on the defensive to release French troops and had taken the risk of maintaining as few troops as possible opposite the British. The German defences were hurriedly strengthened and more troops brought in to garrison them. The French had also expected that the British troops would only release French soldiers from trench-holding and that British participation in French attacks would be a secondary activity. After the battle French commanders made more effort to co-operate with the BEF and plan a combined attack from Arras to Armentières.[15]

The expenditure of artillery ammunition on the first day had been about 30 percent of the field-gun ammunition in the First Army, which was equivalent to 17 days' shell production per gun.[16] After the Battle of Neuve Chapelle, Field Marshal Sir John French reported to Field Marshal Lord Kitchener, British Secretary of State for War, that fatigue and the shortage of ammunition had forced a suspension of the offensive. On 15 March French abandoned the offensive as the supply of field-gun ammunition was inadequate. News of the ammunition shortage led to the Shell Crisis of 1915 which, along with the failed attack on the Dardanelles, brought down the Liberal British government under the Premiership of H. H. Asquith. He formed a new coalition government and appointed Lloyd George as Minister of Munitions. It was a recognition that the whole economy would have to be adapted for war, if the Allies were to prevail on the Western Front. The battle also affected British tactical thinking with the idea that infantry offensives accompanied by artillery barrages could break the stalemate of trench warfare.[17]

Casualties

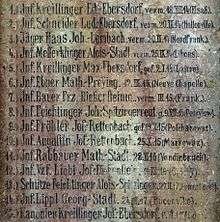

40,000 Allied troops took part during the battle and suffered 7,000 British and 4,200 Indian casualties. The 7th Division had 2,791 casualties, the 8th Division 4,814 losses, the Meerut Division 2,353 casualties and the Lahore Division 1,694 losses.[18] German casualties from 9–20 March were c. 10,000 men.[19] The 6th Bavarian Reserve Division lost 6,017 men from 11–13 March, Bavarian Reserve Infantry Regiment 21 losing 1,665 casualties, Infantry Regiment 14 of the VII Corps lost 666 troops from 7–12 March. Infantry Regiment 13 lost 1,322 casualties from 6–27 March.[18]

Commemoration

War graves of the Indian Corps and the Indian Labour Corps are found at Ayette, Souchez and Neuve-Chapelle.[20]

Victoria Cross

- Rifleman Gabbar Singh Negi, 2nd / 39th Garhwal Rifles.[21][lower-alpha 1]

- Corporal W. Anderson, 2nd Green Howards.[23]

- Captain C. C. Foss, 2nd Bedfordshire Regiment.[24]

- Private J. Rivers, 1st Battalion, The Sherwood Foresters.[25]

- Lance Corporal W. D. Fuller, 1st battalion, The Grenadier Guards.[26]

- Private E. Barber, 1st Battalion The Grenadier Guards.[26]

- Private W. Buckingham, 2nd Leicestershire Regiment.[27]

- Lieutenant C. G. Martin, 56th Field Company R. E. (3rd Division).[28]

- Company Sergeant-Major H. Daniels, 2nd Battalion, The Rifle Brigade.[29]

- Corporal C. R. Noble, 2nd Battalion, The Rifle Brigade.[29]

See also

Notes

- ↑ The citation for his award, published in the London Gazette, read:

For most conspicuous bravery on 10 March 1915, at Neuve Chapelle. During our attack on the German position he was one of a bayonet party with bombs who entered their [the German] main trench, and was the first man to go round each traverse, driving back the enemy until they were eventually forced to surrender. He was killed during this engagement.[22]

Gabbar Singh Negi was one of 4,700 soldiers of the Indian Army who are commemorated at the Neuve-Chapelle Indian Memorial maintained by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission.[20]

Footnotes

- ↑ Farndale 1986, p. 88.

- ↑ Squadron-Leader 1927, p. 97.

- ↑ Edmonds & Wynne 1927, p. 91.

- 1 2 Edmonds & Wynne 1927, pp. 93–94.

- ↑ Edmonds & Wynne 1927, p. 95.

- ↑ Edmonds & Wynne 1927, p. 98.

- 1 2 Strachan 2003, p. 176.

- ↑ Edmonds & Wynne 1927, p. 105.

- ↑ Edmonds & Wynne 1927, pp. 147–149.

- ↑ Sheffield 2011, pp. 110–111.

- ↑ Edmonds & Wynne 1927, pp. 151–152.

- ↑ Clark 1961, p. 73.

- ↑ Cassar 2004, p. 166.

- ↑ Sheldon 2012, p. 78.

- ↑ Edmonds & Wynne 1927, pp. 152–154.

- ↑ Edmonds & Wynne 1927, p. 149.

- ↑ Griffith 1996, pp. 30–31.

- 1 2 Edmonds & Wynne 1927, p. 151.

- ↑ Humphries & Maker 2010, p. 67.

- 1 2 CWGC 2013.

- ↑ Edmonds & Wynne 1927, p. 94.

- ↑ Gazette 1915, p. 4143.

- ↑ Edmonds & Wynne 1927, p. 132.

- ↑ Edmonds & Wynne 1927, p. 133.

- ↑ Edmonds & Wynne 1927, p. 134.

- 1 2 Edmonds & Wynne 1927, p. 140.

- ↑ Edmonds & Wynne 1927, p. 141.

- ↑ Edmonds & Wynne 1927, p. 143.

- 1 2 Edmonds & Wynne 1927, p. 145.

References

- Books

- Cassar, G. (2004). Kitchener's War: British Strategy from 1914 to 1916. Washington: Brassey's. ISBN 1-57488-708-4.

- Clark, A. (1961). The Donkeys: a Study of the Western Front in 1915. London: Hutchinson. OCLC 271257350.

- Edmonds, J. E.; Wynne, G. C. (1995) [1927]. Military Operations France and Belgium, 1915: Winter 1914–15 Battle of Neuve Chapelle: Battles of Ypres. History of the Great War Based on Official Documents by Direction of the Historical Section of the Committee of Imperial Defence. I (Imperial War Museum and Battery Press repr. ed.). London: Macmillan. ISBN 0-89839-218-7.

- Farndale, M. (1986). Western Front 1914–18. History of the Royal Regiment of Artillery. London: Royal Artillery Institution. ISBN 1-870114-00-0.

- Griffith, P. (1996). Battle Tactics of the Western Front: The British Army's Art of Attack 1916–1918. London: Yale. ISBN 0-30006-663-5.

- Humphries, M. O.; Maker, J. (2010). Germany's Western Front: 1915, Translations from the German Official History of the Great War. II. Waterloo Ont.: Wilfrid Laurier University Press. ISBN 978-1-55458-259-4.

- Sheffield, G. (2011). The Chief: Douglas Haig and the British Army. London: Aurum Press. ISBN 978-1-84513-691-8.

- Sheldon, J. (2012). The German Army on the Western Front, 1915. Barnsley: Pen and Sword. ISBN 978-1-84884-466-7.

- Squadron-Leader pseud. (1927). Basic Principles of Air Warfare: the Influence of Air Power on Sea and Land Strategy. Aldershot: Gale & Polden. OCLC 500116605.

- Strachan, H. (2003). The First World War: To Arms. I. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-014303-518-3.

- Websites

- "London Gazette". London: HMSO. 27 April 1915. ISSN 0374-3721. Retrieved 7 September 2013.

- "Neuve Chapelle Memorial". Commonwealth War Graves Commission website. CWGC. 13 August 2013. Retrieved 7 September 2013.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Battle of Neuve Chapelle. |

- German Official History situation map, 10 March 1915 OÖLB

- Indian and Chinese cemetery, Ayette

- Indian Corps at the Battle of Neuve Chapelle

- The Indian Memorial at Neuve Chapelle

- World War I Document Archive - The Battle of Neuve Chapelle by Count Charles de Souza

- World War One Battlefields: Neuve Chapelle