Timeline of the development of tectonophysics (before 1954)

The evolution of tectonophysics is closely linked to the history of the continental drift and plate tectonics hypotheses. The continental drift/ Airy-Heiskanen isostasy hypothesis had many flaws and scarce data. The fixist/ Pratt-Hayford isostasy, the contracting Earth and the expanding Earth concepts had many flaws as well.

The idea of continents with a permanent location, the geosyncline theory, the Pratt-Hayford isostasy, the extrapolation of the age of the Earth by Lord Kelvin as a black body cooling down, the contracting Earth, the Earth as a solid and crystalline body, is one school of thought. A lithosphere creeping over the asthenosphere is a logical consequence of an Earth with internal heat by radioactivity decay, the Airy-Heiskanen isostasy, thrust faults and Niskanen's mantle viscosity determinations.

Introduction

First there was the Creationism (Martin Luther), and the age of the Earth was thought to have been created circa 4 000 BC. There were stacks of calcareous rocks of maritime origin above sea level, and up and down motions were allowed (geosyncline hypothesis, James Hall and James D. Dana). Later on, the thrust fault concept appeared, and a contracting Earth (Eduard Suess, James D. Dana, Albert Heim) was its driving force. In 1862, the physicist William Thomson (who later became Lord Kelvin) calculated the age of Earth (as a cooling black body) at between 20 million and 400 million years. In 1895, John Perry produced an age of Earth estimate of 2 to 3 billion years old using a model of a convective mantle and thin crust.[1] Finally, Arthur Holmes published The Age of the Earth, an Introduction to Geological Ideas in 1927, in which he presented a range of 1.6 to 3.0 billion years.

Wegener had data for assuming that the relative positions of the continents change over time. It was a mistake to state the continents "plowed" through the sea, although it isn't sure that this fixist quote is true in the original in German. He was an outsider with a doctorate in astronomy attacking an established theory between 'geophysicists'. The geophysicists were right to state that the Earth is solid, and the mantle is elastic (for seismic waves) and inhomogeneous, and the ocean floor would not allow the movement of the continents. But excluding one alternative, substantiates the opposite alternative: passive continents and an active seafloor spreading and subduction, with accretion belts on the edges of the continents. The velocity of the sliding continents, was allowed in the uncertainty of the fixed continent model and seafloor subduction and upwelling with phase change allows for inhomogeneity.

The problem too, was the specialisation. Arthur Holmes and Alfred Rittmann saw it right (Rittmann 1939). Only an outsider can have the overview, only an outsider sees the forest, not only the trees (Hellman 1998b, p. 145). But A. Wegener did not have the specialisation to correctly weight the quality of the geophysical data and the paleontologic data, and its conclusions. Wegener's main interest was meteorology, and he wanted to join the Denmark-Greenland expedition scheduled for mid 1912. So he hurried up to present his Continental Drift hypothesis.[2]

Mainly Charles Lyell, Harold Jeffreys, James D. Dana, Charles Schuchert, Chester Longwell, and the conflict with the Axis powers slowed down the acceptance of continental drifting (Rodney 2012).

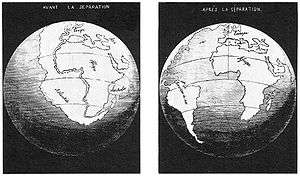

- Abraham Ortelius (Ortelius 1596)[3] (cited in Romm 1994[4]), Francis Bacon (Bacon 1620)[5](cited in Keary & Vine 1990[6]), Theodor Christoph Lilienthal (1756) (cited in Romm 1994,[4] and in Schmeling, 2004[7]), Alexander von Humboldt (1801 and 1845) (cited in Schmeling, 2004[7]), Antonio Snider-Pellegrini (Snider-Pellegrini 1858),[8] and others had noted earlier that the shapes of continents on opposite sides of the Atlantic Ocean (most notably, Africa and South America) seem to fit together (see also Brusatte 2004,[9] and Kious & Tilling 1996[10]).

- Note: Francis Bacon was thinking of western Africa and western South America and Theodor Lilienthal was thinking about the sunken island of Atlantis and changing sea levels.

- Hutton, J (1795). Theory of the Earth: with proofs and illustrations. Edinburgh: Cadell, Davies and Creech. ISBN 1-897799-78-0.

There has been exerted an extreme degree of heat below the strata formed at the bottom of the sea.

- Catastrophism (e.g. Christian Fundamentalism, William Thomson) vs. Uniformitarianism (e.g. Charles Lyell, Thomas Henry Huxley) (Hellman 1998a).

- Term coined by William Whewell.

- Uniformitarism is the prevailing view in the U.S. (Oreskes 2002).

- Charles Lyell assumed that land masses changed their location, but he assumed a mechanism of vertical movement (Krill 2011). James Dwight Dana assumed a permanent location as well, influencing the American fixist school of thought (Irving 2005). It wasn't known that the seafloor isn't mainly granite rock (sial) (as the continental cratons) but mainly basalt rock (sima).

- Quote, Lyell: "Continents therefore, although permanent for whole geological epochs, shift their positions entirely in the course of ages." ((Lyell 1875, p. 258) cited in (Summerhayes 1990))

- Quote, Wallace about Dana: "In 1856, in articles in the American Journal, he discussed the development of the American continent, and argued for its general permanence; and in his Manual of Geology in 1863 and later editions, the same views were more fully enforced and were latterly applied to all continents." ((Dana 1863) cited in (Wallace 2007, p. 342))

- Pratt's isostasy is the prevailing view (Oreskes 2002):

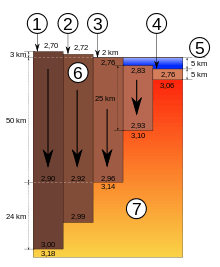

- Airy-Heiskanen Model; where different topographic heights are accommodated by changes in crustal thickness.

- Pratt-Hayford Model; where different topographic heights are accommodated by lateral changes in rock density.

- Vening Meinesz, or Flexural Model; where the lithosphere acts as an elastic plate and its inherent rigidity distributes local topographic loads over a broad region by bending.

- A cooling and contracting Earth is the prevailing view.

- H. Jeffreys was the most important contractionist (Frankel 1987, p. 211), (Jeffreys 1924) - (Jeffreys 1952)

- H. Wettstein (Wegener 1929, pp. 2–3), E. Suess, Bailey Willis and Benjamin Franklin allow horizontal move of the Earth's crust.

- Willis, Bailey; Willis, R. (1929). Geologic Structures. McGraw-Hill book company, inc. p. 131.

the evidences of movement noted in rock structures are so numerous and on so large scale that it is clear that dynamic conditions exist from time to time.

(Holmes 1929a). But Willis was a fixist, as he supported the permanent position of the oceans, although he didn't believe in land-bridges (Krill 2011). - Wettstein, H. (1880). Die Strömungen der Festen, Flüssigen und Gasförmigen und ihre Bedeutung für Geologie, Astronomie, Klimatologie und Meteorologie. Zuerich. p. 406.

- Quote, Benjamin Franklin (1782): "The crust of the Earth must be a shell floating on a fluid interior.... Thus the surface of the globe would be capable of being broken and distorted by the violent movements of the fluids on which it rested".[11][12][13]

- Willis, Bailey; Willis, R. (1929). Geologic Structures. McGraw-Hill book company, inc. p. 131.

- The vertical movement of Scandinavia after the ice age is accepted (recent average uplift c. 1 cm/year). This implies a certain plasticity under the crust (Flint 1947).[14]

- The alpine geology with its theory of thrusting (as geosyncline hypothesis; today's thrust tectonics) accepted horizontal movements. (Suess 1875) cited in (Holmes 1929a)

- 1848 Arnold Escher shows Roderick Murchison the Glarus thrust at the Pass dil Segnas. But Arnold Escher does not publish it as a thrust as it contradicts the geosyncline hypothesis.[15][16]

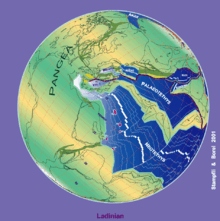

- Eduard Suess proposed Gondwanaland in 1861, as a result of the Glossopteris findings, but he believed that the oceans flooded the spaces currently between those lands. And he proposed the Tethys Sea in 1893. He came to the conclusion that the Alps to the North were once at the bottom of an ocean (Suess 1901).

- The idea of continental drifting shows up for the first time. John Henry Pepper merges Antonio Snider-Pellegrini's map, Evan Hopkins' proof of northward shifting of the continents of his neptunist book and his plutonism ((Hopkins 1844) and (Pepper 1861) cited in (Krill 2011)).

- 1884, Marcel Alexandre Bertrand interpretes the Glarus thrust as a thrust.

- Bertrand, Marcel Alexandre (1884). "Rapports de structure des Alpes de Glaris et du bassin houiller du Nord". Société Géologique de France Bulletin. 3. 12: 318–330.

- Hans Schardt demonstrates that the Prealps are allochthonous.

- Schardt, H. (1884). "Etudes géologiques sur le Pays d'Enhaut vaudois". Bull. Soc. Vaudoise Sci. Nat. 20: 1–183.

- Schardt, H. (1893). "Sur l'origine des Préalpes romandes". Arch. Sci. Phys. Nat. Genève. 3: 570–583.

- Schardt, H. (1898). "Les régions exotiques du versant Nord des Alpes Suisse. Préalpes du Chablais et du Stockhorn et les Klippes". Bull. Soc. Vaudoise Sci. Nat. 34: 113–219.

- 1907, thrust faults get established: Lapworth, Peach and Horne working on parts of the Moine Thrust, Scotland.

- Peach, B.N., Horne, J., Gunn, W., Clough, C.T. & Hinxman, L.W. (1907). "The Geological Structure of the North-west Highlands of Scotland". Memoirs of the Geological Survey, Scotland. Glasgow: His Majesty's Stationery Office.

- Leslie, A.G.; Krabbendam, M. (2009). "Transverse architecture of the Moine Thrust Belt and Moine Nappe, Northern Highlands, Scotland: new insight on a classic thrust belt" (PDF). Bollettino della Societa Geologica Italiana. 128 (2): 295–306. doi:10.3301/IJG.2009.128.2.295.

- Director-Generals of the British Geological Survey: Roderick Murchison (1855–1872) and Archibald Geikie (1881–1901)

- Although Wegener's theory was formed independently and was more complete than those of his predecessors, Wegener later credited a number of past authors with similar ideas:[17] Franklin Coxworthy (between 1848 and 1890),[18] Roberto Mantovani (between 1889 and 1909), William Henry Pickering (1907)[19] and Frank Bursley Taylor (1908). (Wegener 1929)

- 1912-1929: Alfred Wegener develops his continental drift hypothesis. (Wegener 1912a, Wegener 1929)

- In the 1920s Earth scientists refer to themselves as drifters (or mobilists) or fixists (Frankel 1987, p. 206). Terms introduced by the Swiss geologist Émile Argand in 1924 (Krill 2011).

- Moreover, most of the blistering attacks were aimed at Wegener himself, an outsider (PhD in Astronomy) who seemed to be attacking the very foundations of geology.[20]

Controversy

- 1912, Wegener presents his ideas at the German Geological Society, Frankfurt (Wegener 1912a). Karl Erich Andrée (University of Marburg) must have delivered him some references.[2] Strong points:

- Matching of the coastlines of eastern South America and western Africa, and many similarities between the respective coastlines of North America and Europe.

- Numerous geological similarities between Africa and South America, and others between North America and Europe.

- Many examples of past and present-day life forms having a geographically disjunctive distribution.

- Mountain ranges are usually located along the coastlines of the continents, and orogenic regions are long and narrow in shape.

- The Earth's crust exhibits two basic elevations, one corresponding to the elevation of the continental tables, the other to the ocean floors.

- The Permo-Carboniferous moraine deposits found in South Africa, Argentina, southern Brazil, India, and in western, central, and eastern Australia. (Frankel 1987, pp. 205–206)

- Flooded land-bridges contradict isostasy.[2]

- Note I: Wegener described in a sentence the seafloor spreading in the first publication only. But he believed it is a consequence of the continental drift (Wegener 1912a in Jacoby 1981). He abandoned this sentence probably under the advice of Emanuel Kayser, University of Marburg.[2]

- Note II: ‘Petermanns Geographische Mitteilungen’ is one of the leading geographical monthlies of international reputation. (Ruud 1930); Wladimir Köppen (father-in-law), (Köppen 1921a), (Köppen 1921b), (Köppen 1925) and Kurt Wegener (brother), (Wegener 1925), (Wegener 1941), (Wegener 1942) defended there the Continental drift hypothesis in a somewhat mirror controversy (in Demhardt 2005).

- Note III: Although the climate distribution was not always similar to nowadays. In the Carboniferous, coal mines are remains of the Equatorial Realm, glaciation remains are near the South Pole, and between glaciation and Equatorial Realm (centered between latitude 30° and the Tropic of Cancer and the Capricorn) there are remains of deserts (evaporites, salt lakes and sand dunes) (Brusatte 2004, p. 4).[21] These are consequences of the evaporation rate and the atmospheric circulation.

- 1912, Patrick Marshall uses the term "andesite line".[22]

- 1914, the idea of a strong outer layer (lithosphere), overlying a weak asthenosphere is introduced (Barrel 1914).

- H. Jeffreys and others, most important criticisms (Frankel 1987, p. 211), (Hellman 1998, p. 146):

- Continents can not "plow" through the sea, because the seafloor is denser than the continental crust.

- Pole-fleeing force is too weak to move continents and produce mountains.

- Paul Sophus Epstein calculated it to be one millionth of the gravity.

- If the tidal force moves continents, than the Earth's rotation would stop after only one year.

- Daly, Reginald A. (1926). Our Mobile Earth. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons.

- Its opening sentence is Galileo's allegedly muttered rebellious phrase And yet it moves.

- Quote: "Daly,..., seeks to substitute sliding for drifting, assuming that broad domes or bulges form at the earth's surface, and on the flanks of these domes the continental masses slide downward, moving over hot basaltic glass as over a lubricated floor". (pp. 170–291)[23]

- By the mid-1920s, A. Holmes had rejected contractionism and he had introduced a model with convection (Frankel 1987, p. 212), (Holmes 1929a), (Holmes 1929b), (Holmes 1944).

- Note: in a way, not only A. Wegener (Wegener 1912a in Jacobi 1981) but A. Holmes and K. Wegener suggested seafloor spreading as well. (Holmes 1929c in Vine 1966), (Wegener 1942 in Demhardt 2005)

- The Alps were and still are the best investigated orogen worldwide. Otto Ampferer (Austrian Geological Survey) rejected contractionism 1906 and he defended convection, locally only at first. Otto Ampferer even used the word swallowed in a geological sense. The Geological Society Meeting in Innsbruck, held on 29 August 1912, changed a paradigm (T. Termier words, the acceptance of nappes and thrust faults). So that Émile Argand (1916) speculated that the Alps were caused by the North motion of the African shield, and finally accepted this reason 1922, following Wegener's Continental drift theory (Argand 1922 as Staub 1924). Otto Ampferer in the mean time, at the Geological Society Meeting in Vienna, held on 4 April 1919, defended the link between the alpine faulting and Wegener's continental drift.[2][24][25]

- Quote, translation: "The Alpine orogeny is the effect of the migration of the North African shield. Smoothing only alpine folds and nappes on the cross section between the Black Forest and Africa once again, then from the present distance of about 1,800 km, we have an initial gap of around 3,000 to 3,500 km, ie. a pressing of the alpine region, alpine region in a broader sense, of 1,500 km. To this amount must be Africa have moved to Europe. This brings us then to a true large scale continental drift of the African shield". (Staub 1924, p. 257) cited in (Wegener 1929, p. 10)

- W.A.J.M. van Waterschoot van der Gracht, Bailey Willis, Rollin T. Chamberlin, John Joly, G.A.F. Molengraaff, J.W. Gregory, Alfred Wegener, Charles Schuchert, Chester R. Longwell, Frank Bursley Taylor, William Bowie, David White, Joseph T. Singewald, Jr., and Edward W. Berry participated on a Symposium of the American Association of Petroleum Geologists (AAPG, 1926) (van der Gracht 1926)[23] Although the chairman favored the drift hypothesis, it ceased to be an acceptable geological investigation subject in many universities under the influence of Jeffreys (1924) book (Machamer, Pera & Baltas 2000, pp. 72–75).

- Quote, University of Chicago geologist Rollin T. Chamberlin: "If we are to believe in Wegener's hypothesis we must forget everything which has been learned in the past 70 years and start all over again." (Hellman 1998b), (Sullivan 1991, p. 15)

- Quote, Bailey Willis: "further discussion of it merely incumbers the literature and befogs the mind of fellow students. (It is) as antiquated as pre-Curie physics". (Hellman 1998b, p. 150), (Hallam 1983, p. 136)

- Bailey Willis and William Bowie saw the sima with great strength and rigidity through the seismological studies, and tidal forces would act more on the sima (2800 to 3300 kg/m3) as it is denser than the sial (2700 to 2800 kg/m3) (Frankel 1987, p. 211).

- Quote, W. Van Waterschoot van der Gracht (Wilson cycle): "there may have been a pre-Carboniferous "Atlantic" that was closed up during the Caledonian orogenis" (Holmes 1929a).

- By the late-1920s: discovery of the Wadati-Benioff zone by Kiyoo Wadati (two pairs plus one paper, 1927 to 1931) of the Japan Meteorological Agency, and Hugo Benioff of the California Institute of Technology.[26]

- Alexander du Toit's book. (du Toit 1937)

- In 1923, he received a grant from the Carnegie Institution of Washington, and used this to travel to eastern South America to study the geology of Argentina, Paraguay and Brazil.

- 1931: Peacock named the calc-alkaline igneous rock series.

- Peacock, M. A. (1931). "Classification of igneous rock series". Journal of Geology. 39: 54–67. Bibcode:1931JG.....39...54P. doi:10.1086/623788.

- 1931, age of the Earth by the National Research Council of the US National Academy of Sciences.[27]

- 1936, Augusto Gansser-Biaggi interpreted rocks located at the foot of Mount Kailash in the Indian part of the Himalayas as having originated in the seafloor. He brings back a sample with Ammonites of the Norian (Triassic). He later interpreted this Indus-Yarlung-Zangpo Suture Zone (ISZ) as the border between the Indian and the Eurasian Plate.[28]

- David T. Griggs (1939). "A theory of mountain-building". American Journal of Science. 237 (9): 611–650. doi:10.2475/ajs.237.9.611.

- January, 1939: at the annual meeting of the German Geological Society, Frankfurt, Alfred Rittmann opposed the idea that the Mid-Atlantic Ridge was an orogenic uplift (Rittmann 1939).

- "Atlantisheft I" [Atlantis Issue I]. Geologische Rundschau. 30 (3). May 1939.

- Orogenic volcanism (Pacific Ring of Fire) is dominated by calc-alkaline igneous rocks (Calc series), lacking alkali-basaltic magmas (Sodic series); whereas the Mid-Atlantic Ridge (extension) has mainly alkali-basaltic magmas (Ippolito & Marinelli 1981).

- Schwinner (1941) sees subduction as the cause of Wadati-Benioff zone and volcanic activity, but does not link it to continental drifting. He was in a way an anti-drifter.[2]

- Umbgrove, JHF (1942). The Pulse of the Earth (1 ed.). The Hague, NL: Martinus Nyhoff.

- Mid-1940s, paleontologist George Gaylord Simpson finds flaws on the paleontology data. (Frankel 1987, p. 217)

- Alexander du Toit, Glossopteris findings in Russia are an erroneous identification. It was used as argument by anti-drifters (Du Toit 1944).

- 1944, cores of deep ocean sediment show rapid rate of accumulation, suggesting that old oceans are an impossibility ((Revelle 1944) cited in (Bullard 1975)).

- 1948, Felix Andries Vening Meinesz, Dutch geophysicist who believes in convection currents as a result of his work on oceanic gravity anomalies. Highly respected by H. H. Hess, Hess even got a chance to work with him. (Frankel 1987, p. 230), (Vening Meinesz 1948), (Vening Meinesz 1952a), (Vening Meinesz 1952b), (Vening Meinesz 1955), (Vening Meinesz 1959)

- 1949, Niskanen calculates the viscosity under the crust to be 5 1021 CGS units.

- Niskanen, E. (1949). "Publn. Isostatic Inst.". 23. Helsinki.

- 1950, fading of the hypothesis from view.

- Gewers, T. W. (1950). "Transactions of the Geological Society of South Africa". 52 (suppl.): 1.

marked regression away from continental drift

- Gewers, T. W. (1950). "Transactions of the Geological Society of South Africa". 52 (suppl.): 1.

- 1951, Alfred Rittmann shows that crystalline mantle is able to creep at its temperature and pressure and he shows subduction, volcanism and erosion in the mountainous regions. Rittmann (1951), figure 4, p. 293.

- 1951, André Amstutz uses the word subduction.

- Amstutz, André (1951). "Sur l'évolution des structures alpines". Archives des sciences (in French). Géneve (4–5): 323–329.

4) Première phase tectogène, approximativement durant le crétacé: Premières contractions tangentielles et déversements du géanticlinal briançonnais dans la dépression Mt. Rose, par subduction (ce mot n'est-il préférable à celui de sous-charriage ?) de masses Mt. Rose sous de masses St.Bernard; et peut-être simultanément déversements dans la dépression valaisanne-dauphinoise. (pp. 325-326)

- Amstutz, André (1955). "Structures Alpines: subductions successives dans l'Ossola". Comptes rendus de l'Académie des sciences. Paris. 241: 967–969.

- Amstutz, André (1951). "Sur l'évolution des structures alpines". Archives des sciences (in French). Géneve (4–5): 323–329.

- 1953, Adrian E. Scheidegger, anti-drifter.[29]

- E.g.: it had been shown that floating masses on a rotating geoid would collect at the equator, and stay there. This would explain one, but only one, mountain building episode between any pair of continents; it failed to account for earlier orogenic episodes.

See also

Further reading

- Gohau, Gabriel (1990). A History of Geology. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press. ISBN 0-8135-1665-X.

- Wessel, P.; Müller, R. D. (2007). "Plate Tectonics". In Anthony B. Watts. Treatise on Geophysics: Crust and Lithosphere Dynamics. 6. Elsevier. pp. 49–98.

- "NYC Regional Geology: Mesozoic Basins". USGS.

- "Wilson Cycle: and A Plate Tectonic Rock Cycle". Lynn S. Fichter.

References

Notes

- ↑ England, Philip C.; Molnar, Peter; Richter, Frank M. (2007). "Kelvin, Perry and the Age of the Earth". American Scientist. 95 (4): 342–349. doi:10.1511/2007.66.3755.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Flügel, Helmut W. (December 1980). "Wegener-Ampferer-Schwinner: Ein Beitrag zur Geschichte der Geologie in Österreich" [Wegener-Ampferer-Schwinner: A Contribution to the History of the Geology in Austria] (PDF). Mitt. österr. Geol. Ges. (in German). 73.

- ↑ Ortelius 1596.

- 1 2 Romm 1994.

- ↑ Bacon 1620.

- ↑ Keary & Vine 1990.

- 1 2 Schmeling, Harro (2004). "Geodynamik" (PDF) (in German). University of Frankfurt.

- ↑ Snider-Pellegrini 1858.

- ↑ Brusatte 2004, p. 3.

- ↑ Kious & Tilling 1996.

- ↑ "The History of Continental Drift - Before Wegener".

- ↑ Boswell, James (1793). "On the Theory of the Earth - Letter to Abbé Jean-Louis Giraud Soulavie, 22 September 1782". The Scots magazine. Sands, Brymer, Murray and Cochran. 55: 432–433.

- ↑ s:en:Franklin to Abbé Jean-Louis Giraud Soulavie

- ↑ Born, A. (1923). Isostasie und Schweremessung. Berlin.

- ↑ "Historical geology". Geopark Sadona.

- ↑ "Geo-Life: Von der Glarner Doppelfalte zur Glarner Ueberschiebung". geo-life.ch.

- ↑ Wegener 1929, Wegener 1929/1966

- ↑ Coxworthy 1848/1924

- ↑ Pickering 1907

- ↑ "The Wrath of Science". NASA - Earth Observatory.

- ↑ "NYC Regional Geology: Mesozoic Basins". USGS.

- ↑ Benson W. N. (1951). 152–155 "Patrick Marshall" Check

|url=value (help). Transactions and Proceedings of the Royal Society of New Zealand. 79. - 1 2 Longwell, Chester R. "Some Physical Tests of the Displacement Hypothesis" (PDF).

We cannot disregard entirely the suggestion that continental masses have suffered some horizontal movement, because evidence for such movement is becoming ever more apparent in the structure of the Alps and of the Asiatic mountain systems.

- ↑ Krainer, Karl; Hauser, Christoph (2007). "Otto Ampferer (1875-1947): Pioneer in Geology, Mountain Climber, Collector and Draftsman" (PDF). Geo. Alp: Sonderband 1: 91–100.

- ↑ Gansser, Augusto (1973). "Orogene Entwicklung in den Anden, im Himalaja und den Alpen: ein Vergleich". Eclogae Geologicae Helvetiae. Lausanne. 66: 23–40.

- ↑ Honda, Hirochiki (1998). "Kiyoo Wadati and the path to the discovery of the intermediate-deep earthquake zone" (pdf). Episodes. 24 (2): 118–123. Retrieved 7 September 2012.

- ↑ Dalrymple, G. Brent (2001). "The age of the Earth in the twentieth century: a problem (mostly) solved". Special Publications, Geological Society of London. 190 (1): 205–221. Bibcode:2001GSLSP.190..205D. doi:10.1144/GSL.SP.2001.190.01.14.

- ↑ Eichenberger, Ursula (5 September 2008). "Augusto Gansser, Vermesser der Welt". Das Magazin.

- ↑ Scheidegger 1953.

Cited books

- Bacon, Francis (1620). s:en:Novum Organum. England. Translated by Wood, Devey, Spedding, et al.

- P.M.S. Blackett, E.C. Bullard and S.K. Runcorn (ed). A Symposium on Continental Drift, held on 28 October 1965. pp. 323:

- Bullard, E. C.; Everett, J. E.; Smith, A. G. (1965). "The fit of the continents around the Atlantic". In P.M.S. Blackett, E.C. Bullard and S.K. Runcorn. A Symposium on Continental Drift (Oct. 28, 1965). Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A. 258. The Royal Society. pp. 41–51.

- Heezen, B. C.; Tharp, M. (1965). "Tectonic Fabric of the Atlantic and Indian Oceans and Continental Drift". In P.M.S. Blackett; E.C. Bullard; S.K. Runcorn. A Symposium on Continental Drift (Oct. 28, 1965). Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A. 258. The Royal Society. pp. 90–106.

- Wilson, J. Tuzo (1965b). "Evidence from Ocean Islands Suggesting Movement in the Earth". In P.M.S. Blackett; E.C. Bullard; S.K. Runcorn. A Symposium on Continental Drift (Oct. 28, 1965). Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A. 258. The Royal Society. pp. 145–167. JSTOR 73340.

- Carey, S. W. (1958). "The tectonic approach to continental drift". In Carey, S. W. Continental Drift—A symposium, held in March 1956. Hobart: Univ. of Tasmania. pp. 177–363Expanding Earth from p. 311 to p. 349.

- Coats, Robert R. (1962). "Magma type and crustal structure in the Aleutian arc". The Crust of the Pacific Basin. American Geophysical Union Monograph. 6. pp. 92–109.

- Cowen, R.; Lipps, JH, eds. (1975). Controversies in the Earth sciences. St. Paul, MN: West Publishing Co. p. 439. ISBN 0-8299-0044-6.

- Dana, James Dwight (1863). Manual of Geology: Treating of the Principles of the Science with Special Reference to American Geological History. Bliss. p. 805.

- Flint, R. F. (1947). Glacial Geology and the Pleistocene Epoch. New York: John Wiley and Sons. p. 589. ISBN 1-4437-2173-5.

- Frankel, H. (1987). "The Continental Drift Debate". In H.T. Engelhardt Jr; A.L. Caplan. Scientific Controversies: Case Solutions in the resolution and closure of disputes in science and technology. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-27560-6.

- W.A.J.M. van Waterschoot van der Gracht, Bailey Willis, Rollin T. Chamberlin, John Joly, G.A.F. Molengraaff, J.W. Gregory, Alfred Wegener, Charles Schuchert, Chester R. Longwell, Frank Bursley Taylor, William Bowie, David White, Joseph T. Singewald, Jr., and Edward W. Berry (1928). W.A.J.M. van Waterschoot van der Gracht, ed. Theory of Continental Drift: a symposium on the origin and movement of land masses both intercontinental and intracontinental as proposed by Alfred Wegener, A Symposium of the American Association of Petroleum Geologists (AAPG, 1926). Tulsa, OK. p. 240.

- Le Grand, H. E. (1990). "Is one picture worth a thousand experiments?". In Le Grand, H. E. Experimental Inquiries: Historical, Philosophical and Social Studies of Experimentation in Science. Dordrecht: Kluwer. pp. 241–270.

- Hallam, A. (1983). Great Geological Controversies. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. x+182. ISBN 0-19-854430-8.

- Hellman, Hal (1998a). "Lord Kelvin versus Geologists and Biologists - The Age of the Earth". Great Feuds in Science: Ten of the Liveliest Disputes Ever. New York: John Wiley & Sons. pp. 105–120. ISBN 0-471-35066-4.

- Hellman, Hal (1998b). "Wegener versus Everybody - Continental Drift". Great Feuds in Science: Ten of the Liveliest Disputes Ever. New York: John Wiley & Sons. pp. 141–158. ISBN 0-471-35066-4.

- Hess, H. H. (November 1962). "History of Ocean Basins" (PDF). In A. E. J. Engel; Harold L. James; B. F. Leonard. Petrologic studies: a volume to honor of A. F. Buddington. Boulder, CO: Geological Society of America. pp. 599–620.

- Holmes, Arthur (1944). Principles of Physical Geology (1 ed.). Edinburgh: Thomas Nelson & Sons. ISBN 0-17-448020-2.

- Holmes, Arthur (1929b). The Origin of Continents and Oceans.

- Hopkins, Evan (1844). On the connection of geology with terrestrial magnetism. R. Taylor. p. 129.

- Jeffreys, H. (1924). The Earth - its Origin, History and Physical Constitution (1 ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 429.

- Jeffreys, H. (1952). The Earth - its Origin, History and Physical Constitution (3 ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 574. ISBN 0-521-20648-0.

- Marshall Kay, ed. (1969). North Atlantic: geology and continental drift, a symposium. Tulsa, OK: American Association of Petroleum Geologists (AAPG).

- Keary, P; Vine, F. J. (1990). Global Tectonics. Oxford: Blackwell Scientific Publications. p. 302.

- Kearey, Philip; Klepeis, Keith A.; Vine, Frederik J. (2009). Global tectonics (3 ed.). Wiley-Blackwell. p. 482. ISBN 978-1-4051-0777-8.

- Kious, W. Jacquelyne; Tilling, Robert I. (February 2001) [1996]. "Historical perspective". This Dynamic Earth: the Story of Plate Tectonics (Online ed.). U.S. Geological Survey. ISBN 0-16-048220-8. Retrieved 2008-01-29.

Abraham Ortelius in his work Thesaurus Geographicus... suggested that the Americas were 'torn away from Europe and Africa... by earthquakes and floods... The vestiges of the rupture reveal themselves, if someone brings forward a map of the world and considers carefully the coasts of the three [continents].'

- Krill, Allan (2011). Fixists vs. Mobilists: In the Geology Contest of The Century, 1844-1969. ISBN 978-82-998389-1-7.

- Lilienthal, T. (1756). Die Gute Sache der Göttlichen Offenbarung. Königsberg: Hartung.

This is also likely owing to the fact that the coasts of certain lands, situated opposite each other though separated by sea, have a corresponding shape, so that they would be congruent with one another were they to stand side by side; for example, the southern part of America and Africa. For this reason one supposes that perhaps both of these continents were previously attached to each other, either directly, or through the sunken island of Atlantis;...

- Lyell, Charles (1875). Principles of Geology (12 ed.).

- Machamer, Peter; Pera, Marcella; Baltas, Aristides, eds. (2000). Scientific Controversies. New York etc.: Oxford University Press. p. 278. Wegener pp. 72-75.

- Marvin, Ursula B. (1973). Continental Drift: The Evolution of a Concept. Smithsonian Institution Press. p. 239. ISBN 0-87474-129-7 (Dissertation).

- McPhee, John (1998). Annals of the Former World. New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux. ISBN 0-374-10520-0.

- Naomi Oreskes, Homer Le Grand, eds. (December 2001). Plate Tectonics: An Insider's History of the Modern Theory of the Earth. Westview Press. p. 448. ISBN 978-0-8133-3981-8.

- Oreskes, Naomi (1999). The rejection of continental drift: theory and method in American earth science. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-511733-6.

- Ortelius, Abraham (1596). Thesaurus Geographicus (3 ed.). Antwerp: Plantin.

The vestiges of the rupture reveal themselves, if someone brings forward a map of the world and considers carefully the coasts of the three [continents (Europe, Africa and Americas)]

- Pepper, John Henry (1861). The Playbook of Metals. Routledge, Warne, and Routledge. p. 502.

- Phinney, R . A. (1968). The History of the Earth's Crust. Princeton, NJ: Princeton Univ. Press. p. 244.

- Revelle, R. R. (1944). Marine bottom samples collected in the Pacific Ocean by the Carnegie on its Seventh Cruise. Pub. 556, Part 1. Washington: Carnegie Inst.

- Runcorn, S. K., ed. (1962b). Continental Drift. New York and London: Academic Press. p. 338.

- Snider-Pellegrini, Antonio (1858). La Création et ses mystères dévoilés. Paris: Frank and Dentu.

- Stampfli, G.M.; Borel, G.D. (2004). "The TRANSMED Transects in Space and Time: Constraints on the Paleotectonic Evolution of the Mediterranean Domain". In Cavazza W., Roure F., Spakman W., Stampfli G.M., Ziegler P. The TRANSMED Atlas: the Mediterranean Region from Crust to Mantle. Springer Verlag. ISBN 3-540-22181-6.

- Suess, E. (1875). Die Entstehung der Alpen [The Origin of the Alps]. W. Braumüller.

A mass movement, more or less horizontal and progressive, should be the cause underlying the formation of our mountain systems.

- Suess, Eduard (1885-08-19). Das Antlitz der Erde [The Face of the Earth]. Vienna: F. Tempsky. Three volumes, translator: H. B. C. Sollas.

- Sullivan, Walter (1991). Continents in Motion: The New Earth Debate (1 ed.). American Inst. of Physics. p. 425. ISBN 978-0-88318-703-6.

- du Toit, Alexander (1937). Our wandering continents: an hypothesis of continental drifting. Edinburgh: Oliver and Boyd. ISBN 0-8371-5982-2.

- Umbgrove, J.H.F. (1947). The Pulse of the Earth (2 ed.). The Hague, NL: Martinus Nyhoff. p. 359.

- Vening-Meinesz, F.A. (1948). Gravity expeditions at sea 1923-1938. Vol. IV. Complete results with isostatic reduction, interpretation on the results. Delft: Nederlandse Commissie voor Geodesie 9. p. 233. ISBN 978-90-6132-015-9.

- Wallace, Alfred Russel (2007). Darwinism: An Exposition of the Theory of Natural Selection With Some of Its Applications. Cosimo, Inc. p. 516. ISBN 1602064539.

- Wegener, A. (1929). Die Entstehung der Kontinente und Ozeane (in German) (4 ed.). Braunschweig: Friedrich Vieweg & Sohn Akt. Ges. ISBN 3-443-01056-3.

- Wegener, A. (1929). The Origin of Continents and Oceans (1966 ed.). Courier Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-61708-4.

- Windley, B.F. (1996). The Evolving Continents (3 ed.). John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-471-91739-7.

- Ziegler, P.A. (1990). Geological Atlas of Western and Central Europe (2 ed.). Bath: Shell Internationale Petroleum Maatschappij BV, Geological Society Publishing House. p. 239. ISBN 90-6644-125-9.

Cited articles

- Ampferer, O. (1921). "Bemerkung zu der Arbeit von R. Schwinner "Vulkanismus und Gebirgsbildung"". Verh. Geol. Staatsanst. Vienna: 101–124.

- Ampferer, O. (1920). "Geometrische Erwägungen über den Bau der Alpen". Mitt. Geol. Ges. Wien. Vienna. 12: 135–174.

- Anderson, D.L. (14 Sep 2001). "Perspective: Geophysics: Top-down tectonics?". Science. 293 (5537): 2016–2018. doi:10.1126/science.1065448. PMID 11557870.

- Araki, T; Enomoto, S; Furuno, K; Gando, Y; Ichimura, K; Ikeda, H; Inoue, K; Kishimoto, Y; Koga, M (28 July 2005). "Experimental investigation of geologically produced antineutrinos with KamLAND". Nature. 436 (7050): 499–503. Bibcode:2005Natur.436..499A. doi:10.1038/nature03980. PMID 16049478.

- Argand, E. (1916). "Sur l'arc des Alps Occidentales". Eclogae geologicae Helveticae. Lausanne. 14: 145–192.

- Argand, E. (1924). "La Tectonique de l'Asie". Extrait du Compte-rendu du XIIIe Congrès géologique international 1922 (13th International Geological Congress) (in French). Liège. 1 (5): 171–372.

- Argus, Donald F.; Gordon, Richard G.; Heflin, Michael B.; Ma, Chopo; Richard J. Eanes, Pascal Willis, W. Richard Peltier, Susan E. Owen (February 2010). "The angular velocities of the plates and the velocity of Earth's centre from space geodesy". Geophysical Journal International. 180 (3): 913–960. Bibcode:2010GeoJI.180..913A. doi:10.1111/j.1365-246X.2009.04463.x. Cite uses deprecated parameter

|coauthors=(help) - Barker, P.F.; Hill, I.A. (1980). "Asymmetric spreading in back-arc basins". Nature. 285 (5767): 652–654. Bibcode:1980Natur.285..652B. doi:10.1038/285652a0.

- Barrel, J. (1914). "The strength of the Earth's crust". Journal of Geology. 22: 28–48. Bibcode:1914JG.....22...28B. doi:10.1086/622131.

- Becker, T.W. (2008). "Azimuthal seismic anisotropy constrains net rotation of the lithosphere". Geophysical Research Letters. 35 (5): L05303. Bibcode:2008GeoRL..3505303B. doi:10.1029/2007GL032928.

- Bird, P. (2003). "An updated digital model of plate boundaries" (PDF). Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems. 4 (3): 1027. Bibcode:2003GGG.....4.1027B. doi:10.1029/2001GC000252.

- Blackett, P. M. S.; Clegg, J. A.; Stubbs, P. H. S. (July 5, 1960). "An Analysis of Rock Magnetic Data". Proceedings of the Royal Society. Series A, Mathematical and Physical Sciences. 256 (1286): 291–322. doi:10.1098/rspa.1960.0110. JSTOR 2413827.

- Bullard, Edward (1975). "The Emergence of Plate Tectonics: A Personal View". Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 3: 1–31. Bibcode:1975AREPS...3....1B. doi:10.1146/annurev.ea.03.050175.000245.

- Brusatte, Stephen (2004). "John Crerar Writing Prize" (PDF).

|contribution=ignored (help) - Conrad, CP; Lithgow-Bertelloni, C (2002). "How Mantle Slabs Drive Plate Tectonics". Science. 298 (5591): 207–9. Bibcode:2002Sci...298..207C. doi:10.1126/science.1074161. PMID 12364804.

- Conrad, Clinton P.; Behn, Mark D. (May 2010). "Constraints on lithosphere net rotation and asthenospheric viscosity from global mantle flow models and seismic anisotropy" (PDF). Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems. 11 (5): Q05W05. Bibcode:2010GGG....1105W05C. doi:10.1029/2009GC002970. ISSN 1525-2027.

- Cox, A.; Dalrymple, G.; Doell, R. R. (1967). "Reversals of the Earth's Magnetic Field". Scientific American. 216 (2): 44–54. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0267-44.

- Coxworthy, F. (1848/1924). "Electrical Condition or How and Where our Earth was created". London: W. J. S. Phillips. ASIN B00089ITQU. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - Creer, K. M.; Irving, E.; Runcorn, S. K. (1957). "Geophysical interpretation of palaeomagnetic directions from Great Britain". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A. 250 (144): 144–156. Bibcode:1957RSPTA.250..144C. doi:10.1098/rsta.1957.0017. JSTOR 91599.

- Demets, Charles; Gordon, Richard G.; Argus, Donald F.; Stein, S. (May 1990). "Current plate motions". Geophysical Journal International. 101 (2): 425–478. Bibcode:1990GeoJI.101..425D. doi:10.1111/j.1365-246X.1990.tb06579.x.

- Demets, Charles; Gordon, Richard G.; Argus, Donald F. (April 2010). "Geologically current plate motions" (PDF). Geophysical Journal International. 181 (1): 1–80. Bibcode:2010GeoJI.181....1D. doi:10.1111/j.1365-246X.2009.04491.x.

- Demhardt, Imre Josef (2005). "Alfred Wegener's Hypothesis on Continental Drift and Its Discussion in Petermanns Geographische Mitteilungen (1912–1942)" (PDF). Polarforschung. 75 (1): 29–35.

- Dewey, John F.; Bird, John M. (1970). "Mountain Belts and the New Global Tectonics". Journal of Geophysical Research. 75 (14): 2625–2647. Bibcode:1970JGR....75.2625D. doi:10.1029/JB075i014p02625.

- Dietz, Robert S. (June 1961). "Continent and Ocean Basin Evolution by Spreading of the Sea Floor". Nature. 190 (4779): 854–857. Bibcode:1961Natur.190..854D. doi:10.1038/190854a0.

- Dziewonski, A.M.; Woodhouse, J.H. (3 April 1987). "Global images of the Earth's interior". Science. 236 (4797): 37–48. Bibcode:1987Sci...236...37D. doi:10.1126/science.236.4797.37. PMID 17759204.

- Doell, R. R.; Dalrymple, G. B. (May 1966). "Geomagnetic polarity epochs: a new polarity event and the age of the Brunhes-Matuyama boundary". Science. 152 (3725): 1060–1061. Bibcode:1966Sci...152.1060D. doi:10.1126/science.152.3725.1060. PMID 17754815.

- Dott, R. H., Jr. (1961). "Squantum "tillite", Massachusetts - evidence of glaciation or subaqueous mass movement?". Bull. Geol. Soc. Amer. 72 (9): 1289–1305. Bibcode:1961GSAB...72.1289D. doi:10.1130/0016-7606(1961)72[1289:STMOGO]2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0016-7606.

- Ewing, John; Ewing, Maurice (March 1959). "Seismic-refraction measurements in the Atlantic Ocean basins, in the Mediterranean Sea, on the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, and in the Norwegian Sea". Geological Society of America Bulletin. 70 (3): 291–318. Bibcode:1959GSAB...70..291E. doi:10.1130/0016-7606(1959)70[291:SMITAO]2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0016-7606.

- Forsyth, D.W.; Uyeda, S. (1975). "On the relative importance of the driving forces of plate motion". Geophysical Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society. 43: 163–200. doi:10.1111/j.1365-246x.1975.tb00631.x.

- Fukao, Y; Obayashi, M; Inoue, H; Nenbai, M (1992). "Subducting slabs stagnant in the mantle transition zone". Journal of Geophysical Research. 97 (B4): 4809–22. Bibcode:1992JGR....97.4809F. doi:10.1029/91JB02749.

- Hager, Bradford H.; O'Connell, Richard J. (1981). "A Simple Global Model of Plate Dynamics and Mantle Convection". Journal of Geophysical Research. 86 (B6): 4843–4867. Bibcode:1981JGR....86.4843H. doi:10.1029/JB086iB06p04843.

- Heezen, B. C. (1960). "The rift in the ocean floor". Scientific American. 203 (4): 98–110. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican1060-98.

- Heezen, B. C.; Tharp, M. (1961). Physiographic diagram of the South Atlantic, the Caribbean, the Scotia Sea, and the eastern margin of the South Pacific Ocean. Boulder, CO: The Geological Society of America.

- Heezen, B. C.; Tharp, M. (1964). Physiographic diagram of the Indian Ocean, the Red Sea, the South China Sea, the Sulu Sea, and the Celebes Sea. Boulder, CO: The Geological Society of America.

- Heezen, B. C.; Tharp, M. (1966). "A Discussion Concerning the Floor of the Northwest Indian Ocean (Apr. 7, 1966)". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A. 259 (1099). The Royal Society: 137–149.

|chapter=ignored (help) - Heezen, B. C. (October 1966). Lecture at the conference 'What's New on Earth'. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University.

- Hess, H. H. (1959). "The AMSOC hole to the earth's mantle". Transactions American Geophysical Union. 40: 340–345. Bibcode:1959TrAGU..40..340H. doi:10.1029/tr040i004p00340.

- Hess, H.H. (1960a). "Preprints of the 1st International Oceanographic Congress (New York, August 31-September 12, 1959)". Washington: American Association for the Advancement of Science. (A): 33–34.

|chapter=ignored (help) - Hess, H.H. (1960b). "Evolution of ocean basins". Report to Office of Naval Research. Contract No. 1858(10), NR 081-067: 38.

- Holmes, Arthur (April 1929a). "A review of the continental drift hypothesis" (PDF). Mining Magazine: 2–15.

- Holmes, Arthur (1929c). "Radioactivity and Earth movements". Geological Society of Glasgow Transactions. XVIII (1928-1929): 573–580.

- Hurley, P.M.; Melcher, G.C.; Rand, J.R.; Fairbairn, H.W.; Pinson, W.H. (1966). "Geol. Soc. Am. Progr., Ann. Meetings San Francisco (1966)": 100–101 (abstract).

|contribution=ignored (help) - Hurley, P.M.; Rand, J.R.; Pinson Jr, W.H.; Fairbairn, H.W.; De Almeida, F.F.; Melcher, G.C.; Cordani, U.G.; Kawashita, K.; Vandoros, P.; Hurley, P. M.; Almeida, F. F. M.; Melcher, G. C.; Cordani, U. G.; Rand, J. R.; Kawashita, K.; Vandoros, P.; Pinson, W. H.; Fairbairn, H. W. (1967). "Test of continental drift by comparison of radiometric ages". Science. 157 (3788): 495–500. Bibcode:1967Sci...157..495H. doi:10.1126/science.157.3788.495. PMID 17801399.

- Ippolito, F.; Marinelli, G. (September 1981). "Alfred Rittmann". Bulletin of Volcanology. 44 (3): 217–221. Bibcode:1981BVol...44..217I. doi:10.1007/BF02600560.

- Irving, E.; Green, R. (March 1958). "Polar Movement Relative to Australia". Geophysical Journal of the Royal Astronomical Society. 7 (347): 64. Bibcode:1958GeoJI...1...64I. doi:10.1111/j.1365-246X.1958.tb00035.x.

- Irving, E. (1960). "Paleomagnetic pole positions, a survey and analysis". I. Geophys. T. 3.

- Irving, Edward (February 8, 2005). "The Role of Latitude in Mobilism Debates". PNAS. 102 (6): 1821–1828. Bibcode:2005PNAS..102.1821I. doi:10.1073/pnas.0408162101.

- Jacoby, W. R. (January 1981). "Modern concepts of earth dynamics anticipated by Alfred Wegener in 1912". Geology. 9: 25–27. Bibcode:1981Geo.....9...25J. doi:10.1130/0091-7613(1981)9<25:MCOEDA>2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0091-7613.

the Mid-Atlantic Ridge ... zone in which the floor of the Atlantic, as it keeps spreading, is continuously tearing open and making space for fresh, relatively fluid and hot sima [rising] from depth.

- Jordan, Brennan T. (2007). Geological Society of America Special Papers (PDF). 430: 933–944. doi:10.1130/2007.2430(43) http://www.mantleplumes.org/P%5E4/P%5E4Chapters/JordanP4AcceptedMS.pdf. Missing or empty

|title=(help);|chapter=ignored (help) - Kerr, Richard A. (September 1995). "Earth's Surface May Move Itself". Science. 269 (5228): 1214–1215. Bibcode:1995Sci...269.1214K. doi:10.1126/science.269.5228.1214. PMID 17732101.

- Köppen, W. (1921a). "Polwanderungen, Verschiebungen der Kontinente und Klimageschichte". Dr. A. Petermanns Mitteilungen. 67: 1–8, 57–63.

- Köppen, W. (1921b). "Ursachen und Wirkungen der Kontinentalverschiebungen und Polwanderungen". Dr. A. Petermanns Mitteilungen. 67: 145–149, 191–194.

- Köppen, W. (1925). "Muß man neben der Kontinentalverschiebung noch eine Polwanderung in der Erdgeschichte annehmen?". Dr. A. Petermanns Mitteilungen. 71: 160–162.

- Kreemer, C. (2009). "Absolute plate motions constrained by shear wave splitting orientations with implications for hot spot motions and mantle flow". Journal of Geophysical Research. 114 (B10405): B10405. Bibcode:2009JGRB..11410405K. doi:10.1029/2009JB006416.

- Le Pichon, Xavier (15 June 1968). "Sea-floor spreading and continental drift". Journal of Geophysical Research. 73 (12): 3661–3697. Bibcode:1968JGR....73.3661L. doi:10.1029/JB073i012p03661.

- Martinez, F.; Fryer, P.; Baker, N.A.; Yamazaki, T. (1995). "Evolution of backarc rifting: Mariana Trough, 20-24N". Journal of Geophysical Research. 100: 3807–3827. Bibcode:1995JGR...100.3807M. doi:10.1029/94JB02466.

- Marvin, Ursula B. (1966). "Continental Drift". SAO Special Report. 236: 31–74. Bibcode:1966SAOSR.236...31M.

- Maruyama, Shigenori (1994). "Plume tectonics". Journal of the Geological Society of Japan. 100: 24–49. doi:10.5575/geosoc.100.24.

- McAdoo, David (2006). "Symposium on "15 Years of Progress in Radar Altimetry", held on 13 to 18 of March 2006, Venice" (PDF): 7.

|chapter=ignored (help) - McKenzie, Dan; Parker, Robert L. (30 December 1967). "The North Pacific: an example of tectonics on a sphere". Nature. 216 (5122): 1276–1280. Bibcode:1967Natur.216.1276M. doi:10.1038/2161276a0.

- Menard, H.W. (1958). "Development of median elevations in the ocean basins". Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 69: 1179–1186. doi:10.1130/0016-7606(1958)69[1179:domeio]2.0.co;2.

- Menard, H.W. (6 Jan 1967). "Extension of northeastern-pacific fracture zones". Science. 155 (3758): 72–4. Bibcode:1967Sci...155...72M. doi:10.1126/science.155.3758.72. PMID 17799148.

- Molnar, P.; Atwater, T. (1978). "Interarc spreading and Cordilleran tectonics as alternates related to the age of subducted oceanic lithosphere". Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 41 (3): 330–340. Bibcode:1978E&PSL..41..330M. doi:10.1016/0012-821X(78)90187-5.

- Monastersky, Richard (5 October 1996a). "Why is the Pacific so Big? Look Down Deep". Science News: 213.

- Monastersky, Richard (7 December 1996b). "Tibet Reveals Its Squishy Underbelly". Science News: 356.

- Morgan, W. Jason (1968). "Rises, Trenches, Great Faults, and Crustal Blocks" (PDF). Journal of Geophysical Research. 73 (6): 1959–1982. Bibcode:1968JGR....73.1959M. doi:10.1029/JB073i006p01959.

- Morgan, W. Jason (1971). "Convection plumes in the lower mantle". Nature. 230 (5288): 42–43. Bibcode:1971Natur.230...42M. doi:10.1038/230042a0.

- Morgan, W. J. (February 1972). "Plate motions and deep mantle convection" (PDF). The American Association of Petroleum Geologists Bulletin. 56 (2): 203–213. doi:10.1306/819A3E50-16C5-11D7-8645000102C1865D.

- Nelson, K. Douglas; Zhao, W.; Brown, L. D.; Kuo, J.; Che, J.; Liu, X.; Klemperer, S. L.; Makovsky, Y.; Meissner, R. (December 1996). "Partially Molten Middle Crust beneath Southern Tibet: Synthesis of Project INDEPTH Results". Science. 274 (5293): 1684–1687. Bibcode:1996Sci...274.1684N. doi:10.1126/science.274.5293.1684. PMID 8939851.

- Ninkovich, Dragoslav; Opdyke, Neil; Heezen, Bruce C.; Forster, John H. (November 1966). "Paleomagnetic stratigraphy, rates of deposition and tephrachronology in North Pacific deep-sea sediments". Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 1 (6): 476–492. Bibcode:1966E&PSL...1..476N. doi:10.1016/0012-821X(66)90052-5.

- Oreskes, Naomi (2002). "Continental Drift" (PDF). San Diego: University of California.

- Pickering, W.H (1907). "The Place of Origin of the Moon - The Volcani Problems". Popular Astronomy. 15: 274–287. Bibcode:1907PA.....15..274P.

- Rampino, Michael R.; Stothers, Richard B. (5 Aug 1988). "Flood Basalt Volcanism During the Past 250 Million Years". Science. 241 (4866): 663–668. Bibcode:1988Sci...241..663R. doi:10.1126/science.241.4866.663. PMID 17839077.

- Rittmann, Alfred (1939). "Bemerkungen zur 'Atlantis-Tagung' in Frankfurt im Januar 1939" [Comments about the 'Atlantis Conference', Frankfurt, January 1939]. Geologische Rundschau. 30 (3): 284. Bibcode:1939GeoRu..30..284R. doi:10.1007/BF01804845.

- Rittmann, Alfred (1951). "Orogénèse et volcanisme". Archives des sciences. Géneve (4–5): 273–314.

- Rodney H. Grapes. Barry J. Cooper, ed. "Allan Krill, Fixists vs. Mobilists in the Geology Contest of the Century, 1844-1969" (PDF). INHIGEO Newsletter. International Commission on the History of Geological Sciences: 75–77. ISSN 1028-1533.

- Romm, James (3 February 1994). "A New Forerunner for Continental Drift". Nature. 367 (6462): 407–408. Bibcode:1994Natur.367..407R. doi:10.1038/367407a0.

- Rothé, J. P. (1954). "La zone seismique mediane Indo-Atlantique". Proceedings of the Royal Society. 222: 387–397. doi:10.1098/rspa.1954.0081.

- Runcorn, S.K. (1956). "Paleomagnetic comparisons between Europe and North America". Proceedings, Geological Association of Canada. 8: 7785.

- Runcorn, S. K. (March 1959). "On the Permian Climatic Zonation and Paleomagnetism". American Journal of Science. 257 (3): 235–240. doi:10.2475/ajs.257.3.235.

- Runcorn, S. K. (January 1962a). "Towards a Theory of Continental Drift". Nature. 193 (4813): 311–314. Bibcode:1962Natur.193..311R. doi:10.1038/193311a0.

- Ruud, I. (1930). "Die Ursache der Kontinentalverschiebung und der Gebirgsbildung". Dr. A. Petermanns Mitteilungen. 76: 119–124, 174–180.

- Scheidegger, Adrian E. (1953). "Examination of the physics of theories of orogenesis". Geological Society of America Bulletin. 64 (2): 127–150. Bibcode:1953GSAB...64..127S. doi:10.1130/0016-7606(1953)64[127:EOTPOT]2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0016-7606.

- Schwinner, R. (1920). "Vulkanismus und Gebirgsbildung. Ein Versuch". Z. Vulkanologie. Berlin. 5: 175–230.

- Schwinner, R. (1941). "Seismik und tektonische Geologie der Jetztzeit". Z. Geophysik. 17: 103–113.

- Segev, A (2002). "Flood basalts, continental breakup and the dispersal of Gondwana: evidence for periodic migration of upwelling mantle flows (plumes)" (PDF). EGU Stephan Mueller Special Publication Series. 2: 171–191. doi:10.5194/smsps-2-171-2002. Retrieved 5 August 2010.

- Silver, P.G.; Carlson, R.W.; Olson, P. (1988). "Deep slabs, geochemical heterogeneity, and the large-scale structure of mantle convection: Investigation of an enduring paradox". Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences. 16: 477–541. Bibcode:1988AREPS..16..477S. doi:10.1146/annurev.ea.16.050188.002401.

- Staub, R. (1924). "Der Bau der Alpen". Beitr. Z. Geolog. Karte der Schweiz, N. F. Bern. 52: 272.

- Summerhayes, C. P. (1990). "Palaeoclimates". Journal of the Geological Society, London. 147: 315–320. doi:10.1144/gsjgs.147.2.0315.

- Du Toit, A. (1944). "Tertiary Mammals and Continental Drift". American Journal of Science. 242 (3): 145–63. doi:10.2475/ajs.242.3.145.

- Torsvik, T.H.; Van der Voo, R.; Meert, J.G.; Mosar, J.; Walderhaug, H.J. (2001). "Reconstructions of the Continents Around the North Atlantic at About the 60th Parallel" (PDF). Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 187: 55–69. Bibcode:2001E&PSL.187...55T. doi:10.1016/S0012-821X(01)00284-9.

- Torsvik, Trond Helge; Steinberger, Bernhard; Gurnis, Michael; Gaina, Carmen (2010). "Plate tectonics and net lithosphere rotation over the past 150 My" (PDF). Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 291: 106–112. Bibcode:2010E&PSL.291..106T. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2009.12.055. Retrieved 18 June 2010.

- Vening Meinesz, F. A. (1952a). "The Formation of the Continents by Convection". Kon. Ned. Akad. Weten. 55 (527).

- Vening Meinesz, F. A. (1952b). "The Origin of Continents and Oceans - Geologie en Mijnbouw (n.ser.)". 14: 373–384.

- Vening Meinesz, F. A. (1955). "Plastic Buckling of the Earth's Crust: the Origin of Geosynclines". Geological Society of America.

|contribution=ignored (help) - Vening Meinesz, F. A. (1959). "The results of the development of the Earth's topography in spherical harmonics up to the 31st order; provisional conclusions". Koninkl. Ned. Akad. van Wetenschappen Amsterdam. Proc. Ser. B., Phys. Sciences. 62: 115–136.

- Vine, F. J. (16 December 1966). "Spreading of the Ocean Floor: New Evidence" (PDF). Science. 154 (3755): 1405–1415. Bibcode:1966Sci...154.1405V. doi:10.1126/science.154.3755.1405. PMID 17821553.

- Vine, F. J.; Matthews, D. H. (7 September 1963). "Magnetic Anomalies Over Oceanic Ridges" (PDF). Nature. 199 (4897): 947–949. Bibcode:1963Natur.199..947V. doi:10.1038/199947a0.

- Vine, F. J.; Wilson, J. Tuzo (October 1965). "Magnetic Anomalies over a Young Oceanic Ridge off Vancouver Island" (PDF). Science. 150 (3695): 485–9. Bibcode:1965Sci...150..485V. doi:10.1126/science.150.3695.485. PMID 17842754.

- Wegener, Alfred (1912a). "Die Herausbildung der Grossformen der Erdrinde (Kontinente und Ozeane), auf geophysikalischer Grundlage". Petermanns Geographische Mitteilungen. 63: 185–195, 253–256, 305–309.

Diese (gemeint sind "relative geringfuegige Niveaudifferenzen der grossen ozeanischen Becken untereinander") scheinen es auch nahezulegen, die mittelatlantische Bodenschwelle als diejenige Zone zu betrachten, in welche bei der noch immer fortschreitenden Erweiterung des atlantischen Ozeans der Boden desselben fortwaehrend aufreisst und frischem, relativ fluessigen und hochtemperiertem Sima aus der Tiefe Platz macht [This (meaning the "relatively minor differences in level of the large oceanic basin with each other") seem to suggest also to consider the Mid-Atlantic Rift as the zone in which the expansion of the Atlantic Ocean is still ongoing, and its seafloor tears open constantly to make space to fresh, relatively fluid and tempered Sima]

- Wegener, A. (July 1912b). "Die Entstehung der Kontinente". Geologische Rundschau. 3 (4): 276–292. Bibcode:1912GeoRu...3..276W. doi:10.1007/BF02202896. Just an overview of the article in Petermanns Geographische Mitteilungen.

- Wegener, K. (1925). "Die Kontinentalschollen". Dr. A. Petermanns Mitteilungen. 71: 51–53.

- Wegener, K. (1941). "Geophysik und Geographie". Dr. A. Petermanns Mitteilungen. 87: 98–100.

- Wegener, K. (1942). "Die Theorie Alfred Wegeners über die Entstehung der Kontinente und Ozeane". Dr. A. Petermanns Mitteilungen. 88: 178–182. He gives reasons for the paleo connection of the Americas and Eurasia-Africa by naming paleontological similarities, parallelism of coastal forms and the recently researched submarine Atlantic mountain range as ideal seam of continental splits (p. 181).

- Wells, J. W. (1963). "Coral Growth and Geochronometry". Nature. 197 (4871): 948–950. Bibcode:1963Natur.197..948W. doi:10.1038/197948a0.

- White, R.; McKenzie, D. (1989). "Magmatism at rift zones: The generation of volcanic continental margins and flood basalts". Journal of Geophysical Research. 94: 7685–7729. Bibcode:1989JGR....94.7685W. doi:10.1029/JB094iB06p07685.

- Wilson, J. Tuzo (July 1962). "Cabot Fault, an Appalachian Equivalent of San Andreas and Great Glen Faults and Some Implications for Continental Displacement". Nature. 195 (4837): 135–138. Bibcode:1962Natur.195..135W. doi:10.1038/195135a0.

- Wilson, J. Tuzo (February 1963a). "Evidence from Islands on the Spreading of Ocean Floors". Nature. 197 (4867): 536–538. Bibcode:1963Natur.197..536W. doi:10.1038/197536a0.

- Wilson, J. Tuzo (1963b). "A possible origin of the Hawaiian Islands" (PDF). Canadian Journal of Physics. 41 (6): 863–870. Bibcode:1963CaJPh..41..863W. doi:10.1139/p63-094.

- Wilson, J. Tuzo (February 1963c). "Pattern of Uplifted Islands in the Main Ocean Basins". Science. 139 (3555): 592–594. Bibcode:1963Sci...139..592T. doi:10.1126/science.139.3555.592. PMID 17788294.

- Wilson, J. Tuzo (July 1965a). "A new class of faults and their bearing on continental drift" (PDF). Nature. 207 (4995): 343–347. Bibcode:1965Natur.207..343W. doi:10.1038/207343a0. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 6, 2010.

- Wilson, J. Tuzo (13 August 1966). "Did the Atlantic close and then re-open?" (PDF). Nature. 211 (5050): 676–681. Bibcode:1966Natur.211..676W. doi:10.1038/211676a0.

- Wilson, J. Tuzo (December 1968). "A Revolution in Earth Science". Geotimes. Washington DC: American Geological Institute. 13 (10): 10–16.

.png)