Carnegie Institution for Science

The Carnegie Institution for Science (CIS), also called the Carnegie Institution of Washington (CIW), is an organization in the United States established to support scientific research. The institution is headquartered in Washington, D.C.

Areas

Today the Carnegie Institution for Science directs its efforts in six main areas:

1) Astronomy at the Department of Terrestrial Magnetism (Washington, D.C.) and the Observatories of the Carnegie Institution of Washington (Pasadena, CA and Las Campanas, Chile);

2) Earth and planetary science also at the Department of Terrestrial Magnetism and the Geophysical Laboratory (Washington, D.C.);

3) Global Ecology at the Department of Global Ecology (Stanford, CA);

4) Genetics and developmental biology at the Department of Embryology (Baltimore, MD);

5) Matter at extreme states also at the Geophysical Laboratory; and

6) Plant science at the Department of Plant Biology (Stanford, CA).

Financial positions

As of June 30, 2014, the Institution's endowment was valued at $980 million. Expenses for scientific programs and administration was $98.9 million.[1]

History

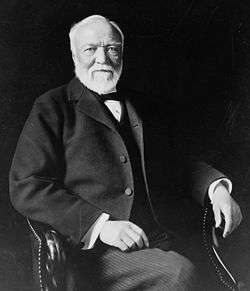

"It is proposed to found in the city of Washington, an institution which...shall in the broadest and most liberal manner encourage investigation, research, and discovery [and] show the application of knowledge to the improvement of mankind..." — Andrew Carnegie, January 28, 1902

Beginning in 1895, Andrew Carnegie contributed his vast fortune toward the establishment of 22 organizations that today bear his name and carry on work in such fields as art, education, international affairs, peace, and scientific research.

In 1901, Andrew Carnegie retired from business to begin his career in philanthropy. Among his new enterprises, he considered establishing a national university in Washington, D.C., similar to the great centers of learning in Europe. Because he was concerned that a new university could weaken existing institutions, he opted for a more exciting, albeit riskier, endeavor—an independent research organization that would increase basic scientific knowledge.

Carnegie contacted President Theodore Roosevelt and declared his readiness to endow the new institution with $10 million. He added $2 million more to the endowment in 1907, and another $10 million in 1911. By some estimates, the value of his endowment in current terms was $500 million. [2]

As ex officio members of the first board of trustees, Carnegie chose the President of the United States, the President of the Senate, the Speaker of the House of Representatives, the secretary of the Smithsonian Institution and the president of the National Academy of Sciences. In all, he selected 27 men for the institution’s original board. Their first meeting was held in the office of the Secretary of State on January 29, 1902, and Daniel Coit Gilman, who had been president of Johns Hopkins University, was elected president. The institution was incorporated by the U.S. Congress in 1903.

Early Grants

Initially, the president and trustees devoted much of the institution’s budget to individual grants in various fields, including astronomy, anthropology—including Maya studies—literature, economics, history and mathematics. Among the researchers who received individual grants were American physicist Albert A. Michelson, paleontologist Oliver Perry Hay, botanist Janet Russell Perkins, Thomas Hunt Morgan and his “fly group”, geologist Thomas Chrowder Chamberlin, historian of science George Sarton, rocket pioneer Robert H. Goddard and botanist Luther Burbank. [3]

The institution also funded archaeological research by Sylvanus Morley at Chichen Itza. [4]

Research of Special Note

Under the leadership of Robert Woodward, who became president in 1904, the board changed its course, deciding to provide major support to departments of research rather than to individuals. This approach allowed them to concentrate on fewer fields and support groups of researchers in related areas over many years. Since the beginning, the Carnegie Institution has been like an explorer—discovering new areas, but often leaving the development to others. This philosophy has fostered new areas of science and has led to unexpected benefits to society, including the development of hybrid corn, radar, the technology that led to Pyrex ® glass, and novel techniques to control genes called RNA interference. Some of Carnegie’s leading researchers from the early and middle years of the 20th century are well known:

- Edwin Hubble, who revolutionized astronomy with his discovery that the universe is expanding and that there are galaxies other than our own Milky Way

- Charles Richter, who created the earthquake measurement scale;

- Barbara McClintock, who won the Nobel Prize for her early work on patterns of genetic inheritance;

- Alfred Hershey, who won the Nobel Prize for determining that DNA, not protein, harbors the genetic recipe for life;

- Vera Rubin, who was awarded the Presidential Medal of Science for her work confirming the existence of dark matter in the universe; and

- Andrew Fire, who with colleagues elsewhere opened up the world of RNA interference, for which he shared a Nobel Prize in 2006

World War II

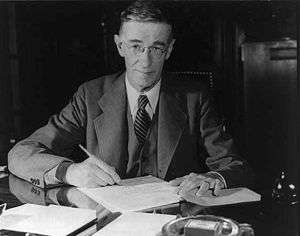

When the United States entered World War II, Vannevar Bush was president of the Carnegie Institution. Several months before, on June 12, 1940, Bush had been instrumental in persuading President Franklin Roosevelt to create the National Defense Research Committee (later superseded by the Office of Scientific Research and Development) to mobilize and coordinate the nation’s scientific war effort. Bush quickly housed the new agency in the Carnegie Institution’s administrative headquarters at 16th and P Streets, NW, in Washington, DC, converting its great rotunda and auditorium into office cubicles. From this location, Bush supervised, among many other projects, the Manhattan Project. Further, Carnegie scientists cooperated in the development of the proximity fuze and mass production of penicillin.[5]

Present

Today, Carnegie scientists continue to be at the forefront of scientific discovery. Working in six scientific departments on the East and West Coasts, Carnegie investigators are leaders in the fields of astronomy, Earth and planetary science, global ecology, genetics and developmental biology, matter at extreme states, and plant science. They seek answers to questions about the structure of the universe, the formation of the Solar System and other planetary systems, the behavior and transformation of matter when subjected to extreme conditions, the origin of life, the function of genes, and the development of organisms from single-celled egg to adult.

The current president of the Carnegie Institution is Matthew P. Scott.

Name

Beginning in 1895, Andrew Carnegie donated his vast fortune to establish 22 organizations around the world that today bear his name and carry on work in fields as diverse as art, education, international affairs, world peace, and scientific research. (See ). The organizations are independent entities and are related by name only.

In 2007, the institution adopted the name "Carnegie Institution for Science" to better distinguish it from the other organizations established by and named for Andrew Carnegie. The new name closely associates the words “Carnegie” and “science” and thereby reveals the core identity. The institution remains officially and legally the Carnegie Institution of Washington, but now has a public identity that more clearly describes its work.

Research

Carnegie investigators are leaders in the fields of astronomy, Earth and planetary science, global ecology, genetics and developmental biology, matter at extreme states, and plant science. The institution has six research departments: the Geophysical Laboratory and the Department of Terrestrial Magnetism, both located in Washington, D.C.; The Observatories, in Pasadena, California, and Chile; the Department of Plant Biology and the Department of Global Ecology, in Stanford, California; and the Department of Embryology, in Baltimore, Maryland.

The Carnegie Institution’s Six Research Departments:

Department of Embryology, Baltimore, Maryland The Department of Embryology was founded in 1913 in affiliation with the department of anatomy at The Johns Hopkins University. It has pursued innovative experimental studies directed toward a fundamental description of human development. In a move designed to foster a closer relationship with the Johns Hopkins Department of Biology, in 1960, the Department moved from the medical school to the Hopkins Homewood campus at 115 West University Parkway. This initiated a new research focus on understanding fundamental developmental mechanisms at the cellular and molecular level. A major focus of the research has been the role played by genes during embryogenesis. The research of the department has developed widely used experimental methodologies. The department has supported a vital postdoctoral program that has allowed it to train generations of biologists. A shared graduate program and many intellectual ties with the Johns Hopkins Department of Biology has helped enhance the work of the department. Embryology Department faculty have been appointed Investigators of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute since 1987.

The Maxine F. Singer research building is a facility that has housed the department since 2005. It is located on the Johns Hopkins Homewood campus at 3520 San Martin Drive. The Department of Embryology is recognized as among the top research centers in cellular, developmental and genetic biology. Three researchers were awarded Nobel Prizes for work done while at the department: Alfred Hershey, Barbara McClintock, and Andrew Fire.

In addition to the Department of Embryology, BioEYES is located at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, PA; Monash University in Melbourne, Australia; the University of Utah in Salt Lake City, UT; and the University of Notre Dame in South Bend, IN.”

Until the 1960s the department's focus was human embryo development. Since then the researchers have addressed fundamental questions in animal development and genetics at the cellular and molecular levels. Some researchers investigate the genetic programming behind cellular processes as cells develop, while others explore the genes that control growth and obesity, stimulate stem cells to become specialized body parts, and perform many other functions.

Geophysical Laboratory, Washington, D.C. Researchers at the Geophysical Laboratory (GL), founded in 1905, examine the physics and chemistry of Earth’s deep interior. The laboratory is a world-renowned center for petrology—the study of rocks. It is also a world leader in high-pressure and high-temperature physics making significant contributions to both Earth and material sciences. The GL, with the Department of Terrestrial Magnetism co-located on the same campus, is additionally a member of the NASA Astrobiology Institute—an interdisciplinary effort to investigate how life evolved on this planet and determine its potential for existing elsewhere. Among their many projects is one dedicated to examining how common rocks found at high-pressure, high-temperature hydrothermal vents at the ocean bottom may have provided the catalyst for life on this planet.

Research at the Geophysical Laboratory is multidisciplinary and encompasses research from theoretical physics to molecular biology. When the Laboratory was first established, its mission was to understand the composition and structure of the Earth as it was known at the time, including the processes that control them. This included developing an understanding of the underlying physics and chemistry as well as the tools necessary for research. During the history of the Laboratory, this mission has extended to include the entire range of conditions since the Earth’s formation. Most recently this study has expanded to cover other planets, both within our own solar system and in other star systems.

Today, as through its history, the Laboratory is at the forefront of developing instruments and procedures for examining materials across a wide range of temperatures and pressures — everything from near absolute zero to hotter than the sun and from ambient pressure to millions of atmospheres. The Laboratory uses diamond-anvil cells coupled with first-principles theory as research tools. It also develops scientific instrumentation and high-pressure technology used at the national x-ray and neutron facilities that it manages. This work addresses major problems in mineralogy, materials science, chemistry, and condensed-matter physics.

Laboratory scientists examine meteorites and comets to follow the evolution of simple to complex molecules in the solar system. They are gaining insights into the origin of life by examining the conditions present in the early Earth. Studying unique ecologies to develop detailed models of their biochemistry helps develop protocols and instrumentation that could assist the search for life on other planets. The protocols and methodologies are tested in regions of the Earth that serve as analogs for conditions found on other planets.

As do all Carnegie departments, the Laboratory supports outstanding young scholars through a strong program of education and training at the pre-doctoral and post-doctoral levels.

Department of Global Ecology, Stanford, California Established in 2002, Global Ecology is the newest Carnegie department in over 80 years. Using innovative approaches, these researchers are picking apart the complicated interactions of Earth’s land, atmosphere, and oceans to understand how global systems operate. With a wide range of powerful tools—from satellites to the instruments of molecular biology—these scientists explore issues such as the global carbon cycle, the role of land and oceanic ecosystems in regulating climate, the interaction of biological diversity with ecosystem function, and much more. These ecologists also play an active role in the public arena, from giving congressional testimony to promoting satellite imagery for the discovery of environmental “hotspots.” In 2007, Department Director Chris Field was among the 25 scientists who accepted the Nobel Peace Prize on behalf of the IPCC, which shared the award with former Vice President Al Gore. [6]

The Department also operates the Carnegie Airborne Observatory (CAO), which was developed by staff scientist Greg Asner. Using laser light, the fixed-wing aircraft scans across the vegetation canopy to produce a detailed 3-D image which can determine the location and size of a tree to within 3.5 feet, or 1.1 meters — a level of detail that had not been reached before. By a combination of these aerial surveys with field surveys and high-resolution satellite mapping, the team has detailed ecological features worldwide. For instance, working with the Peruvian Ministry of Environment, the team was able to determine the actual extent of gold mining in the Peruvian Amazon’s Madre de Dios region. From 1999 to 2012, the extent of mining increased 400%, while since the Great Recession of 2008, forest loss each year had tripled. Before this study, clandestine mining had been able to thrive because it had gone unnoticed. Along with other studies, this technology has been used to map in high resolution the carbon stocks of Panama and Peru. This information could be used as a foundation for carbon-based economic policies. The maps also reveal critical information about the biodiversity of the regions, which is crucial for studies of deforestation and degradation. This in turn is required information to set policies regarding conservation, land use and enforcement. [7]

Department of Plant Biology, Stanford, California

The Department of Plant Biology began as a desert laboratory in 1903 to study plants in their natural habitats. Over time the research evolved to the study of photosynthesis. Today, using molecular genetics and related methods, these biologists study the genes responsible for plant responses to light and the genetic controls over various growth and developmental processes including those that enable plants to survive disease and environmental stress. In addition, the department is a world leader in bioinformatics. It developed an online-integrated database, The Arabidopsis Information Resource (TAIR), that supplies all aspects of biological information on the most widely used model plant, Arabidopsis thaliana. The department uses advanced genetic and genomic tools to study the biochemical and physiological basis of the regulation of photosynthesis and has pioneered tools that use next generation genetic sequencing to systematically characterize unstudied genes. It investigates the mechanisms that plants use to sense and respond to light including the blue light receptors that drive phototropism, the direction of growth towards light, and chloroplast positioning as well as the molecular mechanisms that shape the plant body, especially the production and shape of leaves. It also examines life in extreme environments by studying communities of photosynthetic microbes that live in hot springs. [8]

Department of Terrestrial Magnetism, Washington, D.C. The Department of Terrestrial Magnetism was founded in 1904 to map the geomagnetic field of the Earth. A crucial part of this mission included the use of two ships. The Galilee (ship) was chartered in 1905, but when it proved unsuitable for carrying out magnetic observations, a nonmagnetic ship was specially commissioned. The Carnegie (ship) was built in 1909 and completed seven cruises to measure the Earth's magnetic field before it suffered an explosion and burned. [9] Its captain was J. P. Ault. Over the years the research direction of the department shifted, but the historic goal—to understand the Earth and its place in the universe—has remained the same. Today the department is home to an interdisciplinary team of astronomers and astrophysicists, geophysicists and geochemists, cosmochemists and planetary scientists. These Carnegie researchers are discovering planets outside the Solar System, determining the age and structure of the universe, and studying the causes of earthquakes and volcanoes. With colleagues from the Geophysical Laboratory, these investigators are also helping to define the new and exciting field of astrobiology. The department supports a number of interdisciplinary areas of research. Astronomy and Astrophysics at DTM uses pioneering detection methods to discover and understand planets outside the Solar system. By observing and modeling other planetary systems, researchers are able to apply those implications to our own system. The Geophysics group at DTM studies earthquakes and volcanoes and the Earth’s structures and processes that produce them. Cosmochemists study the origins of the Solar system, the early evolution of meteorites and the nature of the impact process on Earth. Astrobiological research focuses on life’s origins and chemical and physical evolution from the interstellar medium through planetary formation. [10]

The Observatories, Pasadena, California, and Las Campanas, Chile

The Observatories were founded in 1904 as the Mount Wilson Observatory. Mount Wilson transformed our notion of the cosmos with the discoveries by Edwin Hubble that the universe is far larger than had been thought and that it is expanding. Carnegie astronomers today study the cosmos with an unusual twist. Unlike most in their field, they design and build their own instruments to capture the secrets of space. They are tracing the evolution of the universe from the spark of the Big Bang through star and galaxy formation, exploring the structure of the universe, and probing the mysteries of dark matter, dark energy, and the ever-accelerating rate at which the universe is expanding. Carnegie astronomers currently operate from the Las Campanas Observatory, which was established in 1969. Located high in Chile’s Atacama Desert, it affords excellent astronomical observing conditions. As Los Angeles’s light encroached more and more on Mount Wilson, day-to-day operations there were transferred to the Mount Wilson Institute in 1986. The newest additions at Las Campanas, twin 6.5-meter reflectors, are remarkable members of the latest generation of giant telescopes. [11] The Carnegie Institution is currently partnered with several other organizations in constructing the Giant Magellan Telescope.

CASE: Carnegie Academy for Science Education and First Light

In 1989, Maxine Singer, president of Carnegie at that time, founded First Light, a free Saturday science program for middle school students from D.C. public, charter, private, and parochial schools. The program teaches hands-on science, such as constructing and programming robots, investigating pond ecology, and studying the Solar System and telescope building. First Light marked the beginning of CASE, the Carnegie Academy for Science Education. Since 1994 CASE has also offered professional development for D.C. teachers in science, mathematics, and technology.

Administration

The Carnegie Institution's administrative offices are located at 1530 P St., NW, Washington, D.C., at the corner of 16th and P Streets. The building houses the offices of the president, administration and finance, publications, and advancement.

Support for eugenics

In 1920 the Eugenics Record Office, founded by Charles Davenport in 1910 in Cold Spring Harbor, New York, was merged with the Station for Experimental Evolution to become the Carnegie Institution's Department of Genetics. The Institution funded that laboratory until 1939; it employed such anthropologists as Morris Steggerda, who collaborated closely with Davenport. The Carnegie Institution ceased its support of eugenics research and closed the department in 1944. The department's records were retained in a university library. The Carnegie Institution continues its support for legitimate genetic research. Among its notable staff members in that field are Nobel laureates Barbara McClintock, Alfred Hershey and Andrew Fire.

Presidents of the CIW

- Daniel Coit Gilman (1902–1904)

- Robert S. Woodward (1904–1920)

- John C. Merriam (1921–1938)

- Vannevar Bush (1939–1955)

- Caryl P. Haskins (1956–1971)

- Philip Abelson (1971–1978)

- James D. Ebert (1978–1987)

- Edward E. David, Jr. (Acting President, 1987–1988)

- Maxine F. Singer (1989–2002)

- Michael E. Gellert (Acting President, Jan. – April 2003)

- Richard A. Meserve (April 2003 – September 2014)

- Matthew P. Scott (September 1, 2014)

References

- ↑ http://carnegiescience.edu/sites/carnegiescience.edu/files/YB13-14ComboForWeb2-13-15.pdf

- ↑ https://www.measuringworth.com

- ↑ Trefil, James; Margaret Hindle Hazen; Timothy Ferris. Good Seeing. Joseph Henry Press, 2002, pp. 29-31.

- ↑ Trefil, James; Margaret Hindle Hazen; Timothy Ferris. Good Seeing. Joseph Henry Press, 2002, pp. 201-205.

- ↑ Trefil, James; Margaret Hindle Hazen; Timothy Ferris. Good Seeing. Joseph Henry Press, 2002, pp. 77-79.

- ↑ https://earth.stanford.edu/news/chris-field-man-every-climate

- ↑ https://carnegiescience.edu/projects/uncovering-canopy-chemistry-carnegie-airborne-observatory

- ↑ https://dpb.carnegiescience.edu/research/light-life

- ↑ Trefil, James; Margaret Hindle Hazen; Timothy Ferris. Good Seeing. Joseph Henry Press, 2002, pp. 133-136.

- ↑ https://dtm.carnegiescience.edu/research

- ↑ https://obs.carnegiescience.edu/about/history

External links

| Wikisource has the text of the 1920 Encyclopedia Americana article Carnegie Institution of Washington. |

- Official website

- Administration

- Carnegie Academy for Science Education and First Light

- Department of Embryology

- Department of Global Ecology

- Department of Plant Biology

- Department of Terrestrial Magnetism

- Historic American Engineering Record (HAER) No. DC-52-A, "Carnegie Institute of Washington, Department of Terrestrial Magnetism, Standardizing Magnetic Observatory"

- HAER No. DC-52-B, "Carnegie Institute of Washington, Department of Terrestrial Magnetism, Brass Foundry"

- HAER No. DC-52-C, "Carnegie Institute of Washington, Department of Terrestrial Magnetism, Atomic Physics Observatory"

- Geophysical Laboratory

- Observatories

- Magellan Telescope