Pier 70, San Francisco

Coordinates: 37°45′35.34″N 122°23′0.87″W / 37.7598167°N 122.3835750°W

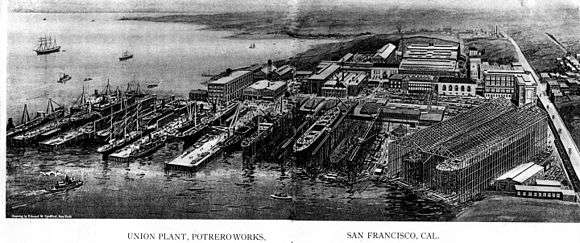

Pier 70 in San Francisco, California, is a historic pier in San Francisco's Potrero Point neighborhood, home to the Union Iron Works and later to Bethlehem Shipbuilding. It was one of the largest industrial sites in San Francisco during the two World Wars. Today, it is regarded as the best preserved 19th century industrial complex west of the Mississippi.[1]

Physical plant

The pier is 65 acres (0.26 km2) in size.[2]

History

The area around Pier 70 has been used for shipbuilding since the Gold Rush.[3] Since becoming home to the Union Iron Works in 1883, Pier 70 has been occupied by a variety of industrial concerns, including the Pacific Rolling Mills, Risdon Iron & Locomotive, Kneass Boat Works, Union Iron Works, Bethlehem Shipbuilding, and BAE Systems.[4]

After Bethlehem acquired Union Iron Works in 1905, the pier also housed Bethlehem Shipbuilding Corporation's administrative offices in Building 101.[5]

Bethlehem Steel sold their holdings in the area to the Port of SF in 1980.[4]

Current state and development

Most of the pier's buildings have been unoccupied since the decline of shipbuilding in the area. However, some of the pier's historic buildings are currently occupied by BAE Systems Ship Repair and by a number of artist studios.[6] Two dry docks are operated by BAE Systems San Francisco Ship Repair, employing approximately 200 people.[7]

The Port of San Francisco currently plans to redevelop the pier for mixed commercial and residential use in partnership with Orton Development, Inc. and Forest City Development. The redevelopment was expected to include roughly a thousand housing units and two million square feet of office space.[2][5] In 2013, plans included a "Crane Cove Park" that would feature the historic cranes in the northern part of the pier complex.[8]

A $120 million restoration and rehabilitation effort for the eight buildings in the pier's historic core began in 2015 and is expected to complete in 2017.[1]

Environmental concerns

Beginning in the 1870s, the manufactured gas plants, iron foundries, steel mills, naval and civilian shipyards, steam generating plants, powder magazines, allied maritime manufacturies and a sugar refinery in the Potrero burned tons of coal, coke, lampblack and later millions of gallons or cubic feet of crude petroleum, refined oil and natural gas in dozens of open hearth furnaces, forges, steam boilers, retort kilns, coke ovens, gas generators and sugar boilers.

These industrial concerns, especially the manufactured gas plants(MGPs) that produced gas for gaslight and power, steam and electricity, poisoned the air and bay waters, the soil and the surrounding communities for decades, leaving behind huge quantities of hydrocarbons, sulphur, acids, powdered carbon, ash, slag, manganese, mercury, lead, copper, cadmium, zinc and other heavy metals. The facilities and their outdoor coal and lampblack stores, tar and fuel oil tanks polluted vast areas of bay mud, artificial fill and millions of gallons of fresh and salt water. Constant dumping and dredging of polluted fill spread the problem to the entire Potrero shoreline while approximately two square miles of Potrero Hill was dynamited and dumped into the bay.

The PG&E plant produced millions of cubic feet of manufactured gas per year from coal and later, oil and natural gas. By 1878, it was consuming nearly 300,000 pounds of coal each day and had an ash pit 200 feet (60 m) long to catch flyash and cinders. By 1905 they produced 4 million cubic feet (110,000 m3) of gas per day. By 1911, they had a capacity of 20 million cubic feet (570,000 m3) per day. The first method of manufacturing gas for urban users utilized coal gasification (1870 to 1907), then oil-gas generators (1888 to 1907), water-gas generators from 1904 to 1915, newer oil-gas generators from 1906 to 1924 and still newer oil-gas generators from 1915 until natural gas was discovered and imported into the Bay area in 1930 and the gas plant was placed on standby. The last time it was fired up was in 1953 and the entire MGP was dismantled in the late 1950s.

The MGPs were built on unpaved soil, their waste stream of coal dust, unburned carbon and lampblack were reused as fuel, dumped into the bay to the east or sent south by the trainload where it was mixed with soil and quarried stone to fill Islais Creek and build new land on bay mud from Army Street (now Cesar Chavez Street) to Candlestick Point east of what is now Third Street. Standard practice of the day was for cinders and ash from the furnaces to be given away or sold for road grading.

The PG&E property in the Potrero lacks a continuous seawall, allowing bay tidal action to twice daily flush the polluted fill. The underground remnants of the shipyards, steel mills, sugar refinery and coal and oil gas production at the mills and the two MGPs is a labyrinth of highly polluted buried coal tramways, distribution tunnels and conduit, remains of huge ash, coal and coke storage pits, coal bunkers, foundations from fuel oil holders, acid and boneblack storage, wooden catchments, fuel lines, underground storage tanks, concrete vaults and sumps. Many were abandoned in place and simply filled in.

These industrial artifacts lie among thousands, if not tens of thousand of wooden piles and railroad ties, abandoned wharves and piers, chemically treated against limnoria and other creatures. The piles are a reverse porcupine of Douglas fir poles, many up to one hundred feet deep, contaminated with a wide array of wood preservatives from arsenic to lead to creosote to crude oil, providing a study in the history of wood preservation technology. Removal would create a direct vertical channel to the deepest bay muds and leaving them in place will continue the downgradient flow of tainted ground water into the bay.

Historic Station A, the huge 1910 brick edifice visible from the surrounding neighborhood, once a state-of-the art oil-fired electrical generating facility, provides evidence of the constant rebuilding in the area as technologies changed. Station A was abandoned in 1979 and remains saturated with PCBs and other pollutants.

Previous dredging at the shipyards during the 1970s was required to be deposited at sea beyond the waters of the state of California. The environmental legacy includes pollution from the Navy's tenure during both world wars through the 1960s and includes illegally dumped wastes in the pier 70-72 landfill.

On top of the historic pollution, more recent insults in the Potrero include sandblasted lead paints in the shipways, leaking waste barrels and underground diesel oil storage tanks. In 1986, the shipyard was sued by the city for mishandling PCB-laden electrical equipment and periodic discharges of raw sewage.

Currently, the city uses the area for storage of towed and abandoned automobiles that leak fluids onto broken pavement that drains toward the bay. The Pick Your Parts Auto Dismantler resides on dirt lots adjacent to the working Mirant power plant, and a toxic dump exists at what was called the Wilson Warehouse to the north.

Numerous trucking companies and a truck marshaling yard, covered by asphalt and pierced by pollution test wells, lie directly north of the PG&E (now Mirant) power plant on former Naval ship building ways that were backfilled in 1970 with construction rubble, soil, concrete and non-permitted wastes. Chemicals found in limited testing in bay mud and in the old Navy slips include hydrocarbons, benzene, toluene, ethylbenzene, chlorobenzene, and xylene. Other wastes identified include paint, oil, batteries, thinner, adhesives, herbicides, acids, and unknown 55-US-gallon (210 L) drums. The two major owners of the filled land in the Potrero are the Port of San Francisco and PG&E, before selling out to Mirant. The environmental liabilities still belong to PG&E.

Historic buildings

Potrero Point is eligible for the National Register as an historic district for its contribution to three war efforts (Spanish–American War, World War I & World War II) and because of the 19th century buildings that remain. Some of the buildings are individually eligible for landmarking for their architectural and historic merit. Worthy of historical landmark status are the 1917 Frederick Meyer Renaissance Revival Bethlehem office building, the Charles P. Weeks designed 1912 Power House#1, the 1896 Union Iron Works office designed by Percy & Hamilton and the huge 1885 Machine shops.

Notable ships built or drydocked at the pier

- From 2001-2008, the pier housed the SS Oceanic (also known as the SS Independence), the last liner built in the United States to sail under the American flag.[9]

- In 2012, the Liberty Ship Jeremiah O'Brien was restored in the Pier 70 dry dock.[10]

- El Primero launched in 1893

- USS Oregon (BB-3) launched in 1893

- USS Wisconsin (BB-9) launched in 1898

- Berkeley, Southern Pacific Railroad ferryboat on San Francisco Bay, constructed simultaneously with the USS Wisconsin in an adjacent drydock, launched in 1898

- USS Ohio (BB-12) launched in 1901

- USS Monterey (BM-6) launched in 1891

- USS Wyoming (BM-10) launched in 1900

- USS Wheeling (PG-14) launched in 1897

- USS Marietta (PG-15) launched in 1897

- USS Charleston (C-2) launched in 1888

- USS San Francisco (C-5) launched 26 October 1889

- USS Olympia (C-6) launched in 1892

- USS Tacoma (CL-20) a Denver class cruiser launched in 1903

- USS Milwaukee (C-21) a St. Louis class cruiser launched in 1904

- The four Atlanta class cruisers; USS Oakland, USS Reno, USS Flint, and USS Tucson, for the United States Navy in 1945 and 1946

- Japanese cruiser Chitose launched in 1898

- Adder class submarines USS Grampus and USS Pike for the United States Navy in 1902 and 1903

- Tanker SS Acme for the United States Shipping Board in 1916

- Bainbridge class destroyers USS Paul Jones (DD-10), USS Perry (DD-11) and USS Preble (DD-12) for the United States Navy Between 1900 and 1902

- 28 Wickes class destroyers for the United States Navy between 1917 and 1919

- 39 Clemson class destroyers for the United States Navy between 1918 and 1921

- Gridley class destroyers USS McCall and USS Maury for the United States Navy in 1937 and 1938

- 9 Benson class destroyers for the United States Navy in 1941 and 1942

- 12 Buckley class destroyer escorts for the United States Navy in 1943 and 1944[4]

- 16 Fletcher class destroyers for the United States Navy in 1942 and 1943

- 6 Allen M. Sumner class destroyers for the United States Navy in 1944 and 1945

- Gearing class destroyers USS William C. Lawe, USS Lloyd Thomas and USS Keppler for the United States Navy in 1945 and 1946

Ships reconstructed by the Union Iron Works include:

- SS Columbia - Refitted unsuccessfully due to heavy damage caused by the 1906 San Francisco earthquake. Refit and repairs completed elsewhere.[3]

References

- 1 2 Flynn, Katherine. "Transitions: Saved—Pier 70 Historic Core". savingplaces.org. National Trust for Historic Preservation. Retrieved 2016-10-08.

- 1 2 Wildermuth, John (April 29, 2014). "Pier 70 project set for presentation". SFGate. Retrieved August 19, 2014.

- ↑ Wilson, Ralph. "Pier 70: History". Retrieved August 19, 2014.

- 1 2 "Pier 70 Subdistrict Fact Sheet". Port of San Francisco. Retrieved 2014-10-22.

- 1 2 WATERFRONT / Developers face pier pressure / Pier 70 poses complex land-use problems, visions

- ↑ SFGov: Port of San Francisco: Pier 70 Area

- ↑ Byloos, Morgane (September 2012). "Pier 70 Set for Major Renovation". Potrero View. Retrieved 26 October 2014.

- ↑ Bevk, Alex (12 September 2013). "What's Up With the New Crane Cove Park in the Dogpatch?". Curbed. Retrieved 26 October 2014.

- ↑ Last U.S. ocean liner heads into the unknown

- ↑ "SS Jeremiah O'Brien In Drydock". MojoSail. 8 February 2012. Retrieved 26 October 2014.

External links

- History of Pier 70, including map

- Port of San Francisco Pier 70 Information Page

- Pier 70 : Curbed SF

- : Potrero Point