Paleontology in New York (state)

Paleontology in New York refers to paleontological research occurring within or conducted by people from the U.S. state of New York. New York has a very rich fossil record, especially from the Devonian. However, a gap in this record spans most of the Mesozoic and early Cenozoic.

Much of New York was covered in seawater during the early part of the Paleozoic era. This sea came to be inhabited by invertebrates like brachiopods, conodonts, eurypterids, jellyfish, and trilobites. Local marine vertebrates included arthrodires, chimaeroids, lobe-finned fishes, and lungfish. By the Devonian the state was home to some of the oldest known forests.

The Carboniferous and Permian are missing from the local rock record. Little is known about Mesozoic New York, but during the early part of the era, carnivorous dinosaurs left behind footprints which later fossilized. The early to mid Cenozoic is also mostly absent from the local rock record. However, evidence indicates that during the Ice Age the state was worked over by glaciers, and home to creatures like giant beavers and mammoths.

The Silurian sea scorpion Eurypterus remipes is the New York state fossil.

Prehistory

New York has a very rich fossil record.[1] Little evidence remains of New York's Precambrian life, although some were preserved in the Adirondack region of the state. New York was covered by a shallow sea during the Late Cambrian.[2] Jellyfish inhabited the state at this time.[3] Other inhabitants of this sea included brachiopods, clams, and trilobites. These groups continued to inhabit this sea into the Ordovician.[2] The terrestrial Ordovician rocks of New York record the process of a coastal plain encroaching westward into an inland sea from a chain of mountains rising along the easternmost edge of North America.[3] Local sea levels had dropped by the ensuing Silurian period. As the sea level lowered the waters covering the western part of the state became shallower and the salt more highly concentrated.[2]

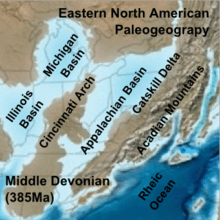

Devonian

Rocks laid down during the Devonian are the best exposed fossil-bearing deposits in the state.[1] Marine invertebrates of Devonian New York included brachiopods, clams, corals, eurypterids, hydras, snails, sponges (some of which attained "huge" sizes[3]), starfish, and trilobites. Conodonts were also present. The fishes of Devonian New York included small arthrodires, chimaeroids, crossopterygians, lungfishes, and ostracoderms.[4] Central and southern New York were home to a westward-flowing river system during the Devonian accompanied by a delta known as the Catskill Delta. This delta was home to some of the world's oldest known forests, such as the Gilboa Forest.[2] It consisted of plants like seed ferns in the genus Eospermatopteris, two species of lycopods that resembled ground pines and club mosses, creeping vines, ferns, and relatives of modern horsetails.[5] The Carboniferous and Permian periods span a gap in the local rock record. During this interval local sediments were being eroded away rather than deposited.[2]

Mesozoic

Mesozoic strata are largely absent in New York.[1] Nevertheless, evidence suggests that during the Triassic the geologic forces responsible for the breakup of Pangaea formed rift basins in the state.[2] Dinosaur footprints of the ichnogenus Grallator were left behind to fossilize in Nyack Beach State Park of Haverstraw during the Late Triassic.[6] Other kinds of reptiles contemporary with the dinosaurian trackmakers left behind their own footprints to fossilize.[6] During the ensuing Jurassic, rift basin formation continued in the state as Pangea divided.[2]

Cenozoic

Like the Mesozoic, strata dating back to the early portion of the Cenozoic are largely absent from New York's rock record.[1] However, during the Quaternary glaciers scoured the state, reshaping its topography and leaving behind significant sedimentary deposits.[2] Local Pleistocene wildlife is known to have included giant beavers, Short-faced bears, giant bison, caribou, deer, Stag-moose, foxes, horses, mammoths, peccaries, American mastodon, and California tapirs.[7]

History

Indigenous interpretations

When large fossils bones and teeth were found eroding out of a creek in the Hudson Valley, the local indigenous people criticized the Dutch Farmers for being skeptical about the natives' belief that the valley had once been inhabited by giants. The local people adhering to this interpretation of the ancient remains likely included the Abenakis, Algonquin Mohicans, Pequots and others who spoke the Iroquois language. They called the ancient giants Weetucks or Maushops, which were believed to have lived eight to ten generations ago.[8] They believed the giants were as tall as trees and hunted bears by knocking them down from the trees.[9] The giants could gather many sturgeons at a time by wading out into river water 12–14 feet deep.[10]

Native American traditions of ancient giants often portray them as neither quite animal or quite human. There is also variation among legends regarding whether or not the giants were dangerous to people. Some local traditions insist that the giants were not a threat to local people and if offered meat were even safe for people to interact with. Nevertheless, these traditions portray the local humans as terrified of the giants. The Delaware and Mohican people believed, by contrast, in ancient giant "naked" bears who hunted the indigenous people of the eastern United States. The last of these monstrous creatures was said to have been killed hundreds of years ago on a cliff at the Hudson River. According to Cotton Mather, there was universal consensus among the Native Americans living within a hundred miles of the Claverack discovery that the remains were verification of their tales of ancient giants. According to the Albany Indians the giant was called Maughkompos.[11] Mather himself attributed the bones to wicked giants that drowned in Noah's Flood in a work written the next year.[12] In actuality the 1705 discovery at Claverack were of the state's first scientifically documented mastodon fossils.[5][12]

Scientific research

One significant event from the early 19th century was the 1817 organization of the New York Lyceum of Natural History (forerunner of the New York Academy of Sciences) by Samuel L. Mitchill.[13] In 1823, publication began of the Annals of the Lyceum.[13] Later, during the 1840s, a particularly spectacular mastodon specimen was found in shell marls near Newburgh. The Warren Mastodon, as the specimen became known, was so well preserved that Dr. Asa Gray was able to analyze its stomach contents and help reconstruct the flora of the ancient forest it fed in. The specimen was curated by the American Museum of Natural History.[5]

1869 was an important year for New York paleontology. In 1869 the American Museum of Natural History was organized.[14] 1869 was also the starting year of excavation at Gilboa Forest, an extraordinary collection of Devonian plants regarded as one of the first forests to ever exist. Among the plants found were seed ferns in the genus Eospermatopteris, two species of lycopods that resembled ground pines and club mosses, creeping vines, ferns, and relatives of modern horsetails.[5] Natural History, the magazine of the American Museum of Natural History, began to be published in 1897.[14]

Excavation of the Gilboa petrified forest continued on into the early twentieth century, but by 1921 excavation at Gilboa Forest had completed.[5] Prior to 1933 very few fossils were known in New York. Among the early finds were the Cambrian jellyfish and eurypterids.[3] Only 15 mammoth finds had been made before 1933.[7] However, mastodon remains had become relatively common. By 1933, more than a hundred mastodon specimens had been dug up in New York.[5] More recent was the 1984 designation of the Silurian sea scorpion Eurypterus remipes as the New York state fossil.[15]

People

Births

- Truman H. Aldrich was born in Palmyra on October 17, 1848.

- John Alroy was born in 1966.

- Charles Emerson Beecher was born in Dunkirk on October 9, 1856.

- Stephen Jay Gould was born in Bayside on September 10, 1941.

- Ulysses S. Grant IV was born in Salem Center on May 23, 1893.

- William King Gregory was born in Greenwich Village on May 19, 1876.

- Othniel Charles Marsh was born in Lockport on October 29, 1831.

- John Ostrom was born in New York City on February 18, 1928.

- Alfred Romer was born in White Plains on December 28, 1894.

- Charles Doolittle Walcott was born in New York Mills on March 31, 1850.

Deaths

- J. C. McConnell died in Liberty on July 25, 1904.

- William King Gregory died in Woodstock on December 29, 1970 at age 94.

- Stephen Jay Gould died in Manhattan on May 20, 2002 at age 60.

Natural history museums

- American Museum of Natural History, New York City

- Buffalo Museum of Science, Buffalo

- Dinosaur Walk Museum, Riverhead

- Museum of Long Island Natural Sciences, Stony Brook University, Stony Brook

- Natural History Museum of the Adirondacks, The WILD Center, Tupper Lake

- New York State Museum, Albany

- Niagara Science Museum, Niagara Falls

- Paleontological Research Institution, Ithaca

- Pember Museum of Natural History, Granville

- Vanderbilt Museum, Centerport

Notable Clubs and associations

See also

- Paleontology in Connecticut

- Paleontology in Massachusetts

- Paleontology in New Hampshire

- Paleontology in New Jersey

- Paleontology in Pennsylvania

Footnotes

- 1 2 3 4 Murray (1974); "New York", page 210.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Picconi, Springer, Scotchmoor, and Rieboldt (2006); "Paleontology and geology".

- 1 2 3 4 Murray (1974); "New York", page 211.

- ↑ Murray (1974); "New York", pages 211-212.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Murray (1974); "New York", page 212.

- 1 2 Weishampel and Young (1996); "Pennsylvania/New Jersey/New York (Stockton Formation)", page 90.

- 1 2 Murray (1974); "New York", page 213.

- ↑ Mayor (2005); "Giants at Claverack, New York, 1705", page 34.

- ↑ Mayor (2005); "Giants at Claverack, New York, 1705", page 35.

- ↑ Mayor (2005); "Giants at Claverack, New York, 1705", pages 35-36.

- ↑ Mayor (2005); "Giants at Claverack, New York, 1705", page 36.

- 1 2 Weishampel and Young (1996); "Noah's Flood", page 53.

- 1 2 Weishampel and Young (1996); "The Great Institutions", page 78.

- 1 2 Weishampel and Young (1996); "The Great Institutions", page 79.

- ↑ New York State Library (2009); "New York State Fossil - Eurypterus Remipes".

- 1 2 Garcia and Miller (1998); "Appendix C: Major Fossil Clubs", page 197.

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Paleontology in New York. |

| Wikisource has original works on the topic: Paleontology in the United States#New York |

- Garcia; Frank A. Garcia; Donald S. Miller (1998). Discovering Fossils. Stackpole Books. p. 212. ISBN 0811728005.

- Mayor, Adrienne. Fossil Legends of the First Americans. Princeton University Press. 2005. ISBN 0-691-11345-9.

- Murray, Marian. 1974. Hunting for Fossils: A Guide to Finding and Collecting Fossils in All 50 States. Collier Books. 348 pp.

- New York State Fossil - Eurypterus Remipes. New York State Library. Last Updated: April 27, 2009. Accessed 12-31-12.

- Picconi, Jane, Dale Springer, Judy Scotchmoor, Sarah Rieboldt. July 21, 2006. "New York, US." The Paleontology Portal. Accessed September 21, 2012.

- Weishampel, D.B. & L. Young. 1996. Dinosaurs of the East Coast. The Johns Hopkins University Press.

External links

- Geologic units in New York

- Paleoportal: New York

- Devonian Fossils of Western New York and Collecting Locations