Ottoman battleship Abdül Kadir

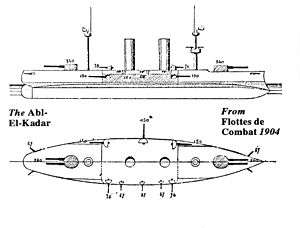

Plan and side views of the rearmed ship | |

| Class overview | |

|---|---|

| Name: | Abdül Kadir |

| Operators: |

|

| Planned: | 1 |

| Cancelled: | 1 |

| History | |

| Namesake: | Abdul Qadir |

| Ordered: | 1890 |

| Builder: | Tersane-i Amire, Constantinople |

| Laid down: | 1892 |

| Fate: | Scrapped, 1909 |

| General characteristics (as designed) | |

| Type: | Pre-dreadnought battleship |

| Displacement: | 8,100 long tons (8,230 t) |

| Length: | 340 ft (103.6 m) |

| Beam: | 65 ft (19.8 m) |

| Draft: | 23 ft 6 in (7.16 m) |

| Propulsion: | 2 shafts, 12,000 ihp (8,948 kW) (estimated) |

| Speed: | 18 knots (33 km/h; 21 mph) (estimated) |

| Armament: |

|

| Armor: | |

Abdül Kadir was a pre-dreadnought battleship laid down in 1892 at the Constantinople imperial dockyard for the Ottoman Navy, the first vessel of this type to be ordered by the Ottoman Empire. The ship was the first capital ship to be laid down by the Ottomans in more than a decade. She was to have a main armament of four 28-centimetre (11 in) guns, with an armoured belt that was 230 mm (9.1 in) thick. Work proceeded on the ship very slowly, primarily the result of a lack of funds; after two years, only the frames for the hull had been erected, and by the time work stopped in 1906, the hull had been only partially plated. The unfinished ship was ultimately broken up for scrap in 1909.

Design

Abdül Kadir was to have been the Ottoman Navy's first pre-dreadnought battleship.[1] She followed a series of ironclad warships built in the 1860s and 1870s. In 1876, Sultan Murad V was deposed; the Ottoman Navy had played a role in the coup, which installed Abdul Hamid II on the throne. The new sultan was as a result suspicious of the navy, and attempted to reduce its power by withholding funding and ordering no new capital ships over the course of the following decade. By the late 1880s, however, the ships built by his predecessors were rapidly becoming obsolescent,[2] especially compared to foreign designs like the British Royal Sovereign-class battleships.[3]

More importantly, the Greek Navy—a major rival of the Ottoman fleet—had ordered three Hydra class ironclad battleships in 1885.[4] These ships, though smaller than the older Ottoman ironclads, were kept in a much better state of readiness than the Ottoman vessels, which were left idle in the Sea of Marmara, with little maintenance done.[5] In 1890, the Ottoman government authorized a large construction program that included two battleships based on the 12,500-metric-ton (12,300-long-ton; 13,800-short-ton) French Hoche, along with several cruisers and smaller vessels. The two Hoche-class battleships were not built;[6] instead, a smaller design, to be named Abdül Kadir, was ordered that year.[7] Along with the elderly central battery ironclad Mesudiye, she would have been one of the largest ships in the Ottoman Navy.[8]

General characteristics and armour

Abdül Kadir was 103.63 m (340.0 ft) long, and had a beam of 19.81 m (65.0 ft) and a draft of 7.16 m (23.5 ft). As designed, she would have displaced 8,100 metric tons (8,000 long tons; 8,900 short tons). She would have been powered by a pair of vertical triple expansion engines each driving a screw propeller, with steam provided by six coal-fired boilers. Both the engines and the boilers would have been manufactured by Tersane-i Amire. The engines were estimated to have been rated at 12,000 indicated horsepower (8,900 kW), which should have provided a top speed of 18 knots (33 km/h; 21 mph). The ship would have had a capacity of 600 metric tons (590 long tons; 660 short tons) of coal.[1][7]

Abdül Kadir was to have had an armoured belt that was 230 mm (9.1 in) thick, and was to have been 2 m (6 ft 7 in) wide. The upper decks above the main belt would not have had any armor protection. The transverse bulkheads connecting the ends of the belt were to have been 105 mm (4.1 in) thick. Her main battery guns were mounted on barbettes that were 150 mm (5.9 in) thick.[1]

Armament

The German firm Krupp had secured the contract to supply the ship's armament. Abdül Kadir was designed to carry a main battery of four 28-centimetre (11 in) guns in two twin turrets on the centerline, one forward and one aft. The secondary battery was to have comprised six 15 cm (5.9 in) guns in casemates. Close-range defense against torpedo boats was to have been provided by a battery of eight 8.8 cm (3.5 in) quick-firing (QF) guns and eight 3.7 cm (1.5 in) QF guns, all in single mounts. Her armament suite was rounded out with six 53.3 cm (21.0 in) torpedo tubes in above water mounts.[1][7] By 1904, her planned armament had been revised, with the 28 cm guns replaced with four 20.3 cm (8.0 in) guns in single turrets, and the number of 15 cm guns increased to ten. The 8.8 cm guns were replaced with 7.62 cm (3.00 in) guns, and the number of 3.7 cm guns was increased to ten. Two of the torpedo tubes were removed.[1]

Construction

Abdül Kadir was laid down at the Imperial Arsenal in Constantinople in October 1892. By 1895, the steel frames for her hull had been erected, but work proceeded very slowly and frequently stopped, primarily due to the chronically tight Ottoman budget.[7] In 1897, for instance, work had been halted for some time, and the contemporary journal Navy and Army Illustrated predicted that the ship would not be finished.[5] Similar large-scale building projects during this period also fell apart due to lack of funds; a major construction program launched in the aftermath of the Ottoman Navy's poor performance in the Greco-Turkish War of 1897 stalled after funds could not be appropriated for the new ships. By 1906, when work on Abdül Kadir stopped for the last time, the hull had been only partially plated. By this time, the blocks that supported the hull during construction had shifted, which destroyed the keel. As a result, the unfinished ship was broken up on the slipway in 1909.[2][7]

See also

Notes

References

- Gardiner, Robert, ed. (1979). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships: 1860–1905. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-85177-133-5.

- Gardiner, Robert; Gray, Randal, eds. (1984). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships: 1906–1921. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-85177-245-5.

- Keltie, J. Scott; Renwick, I. A. P., eds. (1902). The Statesman's Yearbook. 39. London: The Macmillan Company.

- Langensiepen, Bernd & Güleryüz, Ahmet (1995). The Ottoman Steam Navy 1828–1923. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 978-0-85177-610-1.

- Robinson, Charles N., ed. (1897). "The Fleets of the Powers in the Mediterranean". Navy and Army Illustrated. London: Hudson & Kearnes. III: 186–187. OCLC 7489254.