Nucleic acid analogue

Nucleic acid analogues are compounds which are analogous (structurally similar) to naturally occurring RNA and DNA, used in medicine and in molecular biology research. Nucleic acids are chains of nucleotides, which are composed of three parts: a phosphate backbone, a pentose sugar, either ribose or deoxyribose, and one of four nucleobases. An analogue may have any of these altered.[1] Typically the analogue nucleobases confer, among other things, different base pairing and base stacking properties. Examples include universal bases, which can pair with all four canonical bases, and phosphate-sugar backbone analogues such as PNA, which affect the properties of the chain (PNA can even form a triple helix).[2] Nucleic acid analogues are also called Xeno Nucleic Acid and represent one of the main pillars of xenobiology, the design of new-to-nature forms of life based on alternative biochemistries.

Artificial nucleic acids include peptide nucleic acid (PNA), Morpholino and locked nucleic acid (LNA), as well as glycol nucleic acid (GNA) and threose nucleic acid (TNA). Each of these is distinguished from naturally occurring DNA or RNA by changes to the backbone of the molecule.

In May 2014, researchers announced that they had successfully introduced two new artificial nucleotides into bacterial DNA, and by including individual artificial nucleotides in the culture media, were able to passage the bacteria 24 times; they did not create mRNA or proteins able to use the artificial nucleotides. The artificial nucleotides featured 2 fused aromatic rings.

Medicine

Several nucleoside analogues are used as antiviral or anticancer agents. The viral polymerase incorporates these compounds with non-canonical bases. These compounds are activated in the cells by being converted into nucleotides, they are administered as nucleosides since charged nucleotides cannot easily cross cell membranes.

Molecular biology

Nucleic acid analogues are used in molecular biology for several purposes: Investigation of possible scenarios of the origin of life: By testing different analogs, researchers try to answer the question of whether life's use of DNA and RNA was selected over time due to its advantages, or if they were chosen by arbitrary chance;[3] As a tool to detect particular sequences: XNA can be used to tag and identify a wide range of DNA and RNA components with high specificity and accuracy;[4] As an enzyme acting on DNA, RNA and XNA substrates - XNA has been shown to have the ability to cleave and ligate DNA, RNA and other XNA molecules similar to the actions of RNA ribozymes;[3] As a tool with resistance to RNA hydrolysis; Investigation of the mechanisms used by enzyme; Investigation of the structural features of nucleic acids.

Backbone analogues

Hydrolysis resistant RNA-analogues

To overcome the fact that ribose's 2' hydroxy group that reacts with the phosphate linked 3' hydroxy group (RNA is too unstable to be used or synthesized reliably), a ribose analogue is used. The most common RNA analogues are 2'-O-methyl-substituted RNA, locked nucleic acid (LNA) or bridged nucleic acid (BNA), morpholino,[5][6] and peptide nucleic acid (PNA). Although these oligonucleotides have a different backbone sugar or, in the case of PNA, an amino acid residue in place of the ribose phosphate, they still bind to RNA or DNA according to Watson and Crick pairing, but are immune to nuclease activity. They cannot be synthesized enzymatically and can only be obtained synthetically using phosphoramidite strategy or, for PNA, methods of peptide synthesis.

Other notable analogues used as tools

Dideoxynucleotides are used in sequencing . These nucleoside triphosphates possess a non-canonical sugar, dideoxyribose, which lacks the 3' hydroxyl group normally present in DNA and therefore cannot bond with the next base. The lack of the 3' hydroxyl group terminates the chain reaction as the DNA polymerases mistake it for a regular deoxyribonucleotide. Another chain-terminating analogue that lacks a 3' hydroxyl and mimics adenosine is called cordycepin. Cordycepin is an anticancer drug that targets RNA replication. Another analogue in sequencing is a nucleobase analogue, 7-deaza-GTP and is used to sequence CG rich regions, instead 7-deaza-ATP is called tubercidin, an antibiotic.

Precursors to the RNA world

RNA may be too complex to be the first nucleic acid, so before the RNA world several simpler nucleic acids that differ in the backbone, such as TNA and GNA and PNA, have been offered as candidates for the first nucleic acids.

Base analogues

Nucleobase structure and nomenclature

Naturally occurring bases can be divided into two classes according to their structure:

- pyrimidines are six-membered heterocyclic with nitrogen atoms in position 1 and 3.

- purines are bicyclic, consisting of a pyrimidine fused to an imidazole ring.

|

|

| Purine | Pyrimidine |

Artificial nucleotides (Unnatural Base Pairs (UBPs) named d5SICS UBP and dNaM UBP) have been inserted into bacterial DNA but these genes did not template mRNA or induce protein synthesis. The artificial nucleotides featured two fused aromatic rings which formed a (d5SICS–dNaM) complex mimicking the natural (dG–dC) base pair.[7][8][9]

Fluorophores

Commonly fluorophores (such as rhodamine or fluorescein) are linked to the ring linked to the sugar (in para) via a flexible arm, presumably extruding from the major groove of the helix. Due to low processivity of the nucleotides linked to bulky adducts such as florophores by taq polymerases, the sequence is typically copied using a nucleotide with an arm and later coupled with a reactive fluorophore (indirect labelling):

- amine reactive: Aminoallyl nucleotide contain a primary amine group on a linker that reacts with the amino-reactive dye such as a cyanine or Alexa Fluor dyes, which contain a reactive leaving group, such as a succinimidyl ester (NHS). (base-pairing amino groups are not affected).

- thiol reactive: thiol containing nucleotides reacts with the fluorophore linked to a reactive leaving group, such as a maleimide.

- biotin linked nucleotides rely on the same indirect labelling principle (+ fluorescent streptavidin) and are used in Affymetrix DNAchips.

Fluorophores find a variety of uses in medicine and biochemistry.

Fluorescent base analogues

The most commonly used and commercially available fluorescent base analogue, 2-aminopurine (2-AP), has a high-fluorescence quantum yield free in solution (0.68) that is considerably reduced (appr. 100 times but highly dependent on base sequence) when incorporated into nucleic acids.[10] The emission sensitivity of 2-AP to immediate surroundings is shared by other promising and useful fluorescent base analogues like 3-MI, 6-MI, 6-MAP,[11] pyrrolo-dC (also commercially available),[12] modified and improved derivatives of pyrrolo-dC,[13] furan-modified bases[14] and many other ones (see recent reviews).[15][16][17][18][19] This sensitivity to the microenvironment has been utilized in studies of e.g. structure and dynamics within both DNA and RNA, dynamics and kinetics of DNA-protein interaction and electron transfer within DNA. A newly developed and very interesting group of fluorescent base analogues that has a fluorescence quantum yield that is nearly insensitive to their immediate surroundings is the tricyclic cytosine family. 1,3-Diaza-2-oxophenothiazine, tC, has a fluorescence quantum yield of approximately 0.2 both in single- and in double-strands irrespective of surrounding bases.[20][21] Also the oxo-homologue of tC called tCO (both commercially available), 1,3-diaza-2-oxophenoxazine, has a quantum yield of 0.2 in double-stranded systems.[22] However, it is somewhat sensitive to surrounding bases in single-strands (quantum yields of 0.14–0.41). The high and stable quantum yields of these base analogues make them very bright, and, in combination with their good base analogue properties (leaves DNA structure and stability next to unperturbed), they are especially useful in fluorescence anisotropy and FRET measurements, areas where other fluorescent base analogues are less accurate. Also, in the same family of cytosine analogues, a FRET-acceptor base analogue, tCnitro, has been developed.[23] Together with tCO as a FRET-donor this constitutes the first nucleic acid base analogue FRET-pair ever developed. The tC-family has, for example, been used in studies related to polymerase DNA-binding and DNA-polymerization mechanisms.

Natural non-canonical bases

In a cell, there are several non-canonical bases present: CpG islands in DNA (are often methylated), all eukaryotic mRNA (capped with a methyl-7-guanosine), and several bases of rRNAs (are methylated). Often, tRNAs are heavily modified postranscriptionally in order to improve their conformation or base pairing, in particular in/near the anticodon: inosine can base pair with C, U, and even with A, whereas thiouridine (with A) is more specific than uracil (with a purine).[24] Other common tRNA base modifications are pseudouridine (which gives its name to the TΨC loop), dihydrouridine (which does not stack as it is not aromatic), queuosine, wyosine, and so forth. Nevertheless, these are all modifications to normal bases and are not placed by a polymerase. [24]

Base-pairing

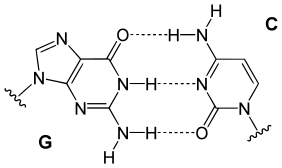

Canonical bases may have either a carbonyl or an amine group on the carbons surrounding the nitrogen atom furthest away from the glycosidic bond, which allows them to base pair (Watson-Crick base pairing) via hydrogen bonds (amine with ketone, purine with pyrimidine). Adenine and 2-aminoadenine have one/two amine group(s), whereas thymine has two carbonyl groups, and cytosine and guanine are mixed amine and carbonyl (inverted in respect to each other).

| Natural basepairs | |

|---|---|

|

|

| A GC basepair: purine carbonyl/amine forms three intermolecular hydrogen bonds with pyrimidine amine/carbonyl | An AT basepair: purine amine/- forms two intermolecular hydrogen bonds with pyrimidine carbonyl/carbonyl |

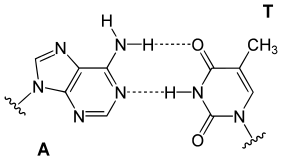

The precise reason why there are only four nucleotides is debated, but there are several unused possibilities. Furthermore, adenine is not the most stable choice for base pairing: in Cyanophage S-2L diaminopurine (DAP) is used instead of adenine (host evasion).[25] Diaminopurine basepairs perfectly with thymine as it is identical to adenine but has an amine group at position 2 forming 3 intramolecular hydrogen bonds, eliminating the major difference between the two types of basepairs (Weak:A-T and Strong:C-G). This improved stability affects protein-binding interactions that rely on those differences. Other combination include,

- isoguanine and isocytosine, which have their amine and ketone inverted compared to standard guanine and cytosine, (not used probably as tautomers are problematic for base pairing, but isoC and isoG can be amplified correctly with PCR even in the presence of the 4 canonical bases)[26]

- diaminopyrimidine and a xanthine, which bind like 2-aminoadenine and thymine but with inverted structures (not used as xanthine is a deamination product)

| Unused basepair arrangements | ||

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

| A DAP-T base: purine amine/amine forms three intermolecular hydrogen bonds with pyrimidine ketone/ketone | An X-DAP base: purine ketone/ketone forms three intermolecular hydrogen bonds with pyrimidine amine/amine | A iG-iC base: purine amine/ketone forms three intermolecular hydrogen bonds with pyrimidine ketone/amine |

However, correct DNA structure can form even when the bases are not paired via hydrogen bonding; that is, the bases pair thanks to hydrophobicity, as studies have shown using DNA isosteres (analogues with same number of atoms), such as the thymine analogue 2,4-difluorotoluene (F) or the adenine analogue 4-methylbenzimidazole (Z).[27] An alternative hydrophobic pair could be isoquinoline, and the pyrrolo[2,3-b]pyridine[28]

Other noteworthy basepairs:

- Several fluorescent bases have also been made, such as the 2-amino-6-(2-thienyl)purine and pyrrole-2-carbaldehyde base pair.[29]

- Metal coordinated bases, such as two 2,6-bis(ethylthiomethyl)pyridine (SPy) with a silver ion or pyridine-2,6-dicarboxamide (Dipam) and a mondentate pyridine (Py) with a copper ion.[30]

- Universal bases may pair indiscriminately with any other base, but, in general, lower the melting temperature of the sequence considerably; examples include 2'-deoxyinosine (hypoxanthine deoxynucleotide) derivatives, nitroazole analogues, and hydrophobic aromatic non-hydrogen-bonding bases (strong stacking effects). These are used as proof of concept and, in general, are not utilised in degenerate primers (which are a mixture of primers).

- The numbers of possible base pairs is doubled when xDNA is considered. xDNA contains expanded bases, in which a benzene ring has been added, which may pair with canonical bases, resulting in four possible base-pairs (8 bases:xA-T,xT-A,xC-G,xG-C, 16 bases if the unused arrangements are used). Another form of benzene added bases is yDNA, in which the base is widened by the benzene.[31]

| Novel basepairs with special properties | ||

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

| A F-Z base: methylbenzimidazole does not form intermolecular hydrogen bonds with toluene F/F | An S-Pa base: purine thienyl/amine forms three intermolecular hydrogen bonds with pyrrole -/carbaldehyde | An xA-T base: same bonding as A-T |

Metal base-pairs

In metal base-pairing, the Watson-Crick hydrogen bonds are replaced by the interaction between a metal ion with nucleosides acting as ligands. The possible geometries of the metal that would allow for duplex formation with two bidentate nucleosides around a central metal atom are: tetrahedral, dodecahedral, and square planar. Metal-complexing with DNA can occur by the formation of non-canonical base pairs from natural nucleobases with participation by metal ions and also by the exchanging the hydrogen atoms that are part of the Watson-Crick base pairing by metal ions.[32] Introduction of metal ions into a DNA duplex has shown to have potential magnetic,[33] conducting properties,[34] as well as increased stability.[35]

Metal complexing has been shown to occur between natural nucleobases. A well-documented example is the formation of T-Hg-T, which involves two deprotonated thymine nucleobases that are brought together by Hg2+ and forms a connected metal-base pair.[36] This motif does not accommodate stacked Hg2+ in a duplex due to an intrastrand hairpin formation process that is favored over duplex formation.[37] Two thymines across from each other in a duplex do not form a Watson-Crick base pair in a duplex; this is an example where a Watson-Crick basepair mismatch is stabilized by the formation of the metal-base pair. Another example of a metal complexing to natural nucleobases is the formation of A-Zn-T and G-Zn-C at high pH; Co+2 and Ni+2 also form these complexes. These are Watson-Crick base pairs where the divalent cation in coordinated to the nucleobases. The exact binding is debated.[38]

A large variety of artificial nucleobases have been developed for use as metal base pairs. These modified nucleobases exhibit tunable electronic properties, sizes, and binding affinities that can be optimized for a specific metal. For, example a nucleoside modified with a pyridine-2,6-dicarboxylate has shown to bind tightly to Cu2+, whereas other divalent ions are only loosely bound. The tridentate character contributes to this selectivity. The fourth coordination site on the copper is saturated by an oppositely arranged pyridine nucleobase.[39] The asymmetric metal base pairing system is orthogonal to the Watson-Crick base pairs. Another example of an artificial nucleobase is that with hydroxypyridone nucleobases, which are able to bind Cu2+ inside the DNA duplex. Five consecutive copper-hydroxypyridone base pairs were incorporated into a double strand, which were flanked by only one natural nucleobase on both ends. EPR data showed that the distance between copper centers was estimated to be 3.7 ± 0.1 Å, while a natural B-type DNA duplex is only slightly larger (3.4 Å).[40] The appeal for stacking metal ions inside a DNA duplex is the hope to obtain nanoscopic self-assembling metal wires, though this has not been realized yet.

Unnatural base pair (UBP)

An unnatural base pair (UBP) is a designed subunit (or nucleobase) of DNA which is created in a laboratory and does not occur in nature. In 2012, a group of American scientists led by Floyd Romesberg, a chemical biologist at the Scripps Research Institute in San Diego, California, published that his team designed an unnatural base pair (UBP).[41] The two new artificial nucleotides or Unnatural Base Pair (UBP) were named d5SICS and dNaM. More technically, these artificial nucleotides bearing hydrophobic nucleobases, feature two fused aromatic rings that form a (d5SICS–dNaM) complex or base pair in DNA.[9][42] In 2014 the same team from the Scripps Research Institute reported that they synthesized a stretch of circular DNA known as a plasmid containing natural T-A and C-G base pairs along with the best-performing UBP Romesberg's laboratory had designed, and inserted it into cells of the common bacterium E. coli that successfully replicated the unnatural base pairs through multiple generations.[43] This is the first known example of a living organism passing along an expanded genetic code to subsequent generations.[9][44] This was in part achieved by the addition of a supportive algal gene that expresses a nucleotide triphosphate transporter which efficiently imports the triphosphates of both d5SICSTP and dNaMTP into E. coli bacteria.[9] Then, the natural bacterial replication pathways use them to accurately replicate the plasmid containing d5SICS–dNaM.

The successful incorporation of a third base pair is a significant breakthrough toward the goal of greatly expanding the number of amino acids which can be encoded by DNA, from the existing 20 amino acids to a theoretically possible 172, thereby expanding the potential for living organisms to produce novel proteins.[43] The artificial strings of DNA do not encode for anything yet, but scientists speculate they could be designed to manufacture new proteins which could have industrial or pharmaceutical uses.[45]

Another demonstration of UBPs were achieved by Ichiro Hirao's group at RIKEN institute in Japan. In 2002, they developed an unnatural base pair between 2-amino-8-(2-thienyl)purine (s) and pyridine-2-one (y) that functions in vitro in transcription and translation, for the site-specific incorporation of non-standard amino acids into proteins.[46] In 2006, they created 7-(2-thienyl)imidazo[4,5-b]pyridine (Ds) and pyrrole-2-carbaldehyde (Pa) as a third base pair for replication and transcription.[47] Afterward, Ds and 4-[3-(6-aminohexanamido)-1-propynyl]-2-nitropyrrole (Px) was discovered as a high fidelity pair in PCR amplification.[48][49] In 2013, they applied the Ds-Px pair to DNA aptamer generation by in vitro selection (SELEX) and demonstrated the genetic alphabet expansion significantly augment DNA aptamer affinities to target proteins.[50]

Orthogonal system

The possibility has been proposed and studied, both theoretically and experimentally, of implementing an orthogonal system inside cells independent of the cellular genetic material in order to make a completely safe system,[51] with the possible increase in encoding potentials[52] Several groups have focused on different aspects:

- novel backbones and base pairs as discussed above

- XNA (Xeno Nucleic Acid) artificial replication/transcription polymerases starting generally from T7 RNA polymerase[53]

- ribosomes (16S sequences with altered anti Shine-Dalgarno sequence allowing the translation of only orthogonal mRNA with a matching altered Shine-Dalgarno sequence)[54]

- novel tRNA encoding non-natural aminoacids. See Expanded genetic code

See also

References

- ↑ Singer, Emily (July 19, 2015). "Chemists Invent New Letters for Nature's Genetic Alphabet". Wired (magazine). Retrieved July 20, 2015.

- ↑ Petersson, B; et al. (Feb 2005). "Crystal structure of a partly self-complementary peptide nucleic acid (PNA) oligomer showing a duplex-triplex network". J Am Chem Soc. 127 (5): 1424–30. doi:10.1021/ja0458726.

- 1 2 Taylor, Alexander I.; Pinheiro, Vitor B.; Smola, Matthew J.; Morgunov, Alexey S.; Peak-Chew, Sew; Cozens, Christopher; Weeks, Kevin M.; Herdewijn, Piet; Holliger, Philipp. "Catalysts from synthetic genetic polymers". Nature. 518 (7539): 427–430. doi:10.1038/nature13982. PMC 4336857

. PMID 25470036.

. PMID 25470036. - ↑ Wang, Qi; Chen, Lei; Long, Yitao; Tian, He; Wu, Junchen. "Molecular Beacons of Xeno-Nucleic Acid for Detecting Nucleic Acid". Theranostics. 3 (6): 395–408. doi:10.7150/thno.5935. PMC 3677410

. PMID 23781286.

. PMID 23781286. - ↑ Summerton, J; Weller, D (1997). "Morpholino Antisense Oligomers: Design, Preparation and Properties". Antisense & Nucleic Acid Drug Development. 7: 187–195. doi:10.1089/oli.1.1997.7.187. PMID 9212909.

- ↑ Summerton, J (1999). "Morpholino Antisense Oligomers: The Case for an RNase-H Independent Structural Type". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1489: 141–158. doi:10.1016/s0167-4781(99)00150-5.

- ↑ Pollack, Andrew (May 7, 2014). "Researchers Report Breakthrough in Creating Artificial Genetic Code". New York Times. Retrieved May 7, 2014.

- ↑ Callaway, Ewen (May 7, 2014). "First life with 'alien' DNA". Nature. doi:10.1038/nature.2014.15179. Retrieved May 7, 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 Malyshev, Denis A.; Dhami, Kirandeep; Lavergne, Thomas; Chen, Tingjian; Dai, Nan; Foster, Jeremy M.; Corrêa, Ivan R.; Romesberg, Floyd E. (May 7, 2014). "A semi-synthetic organism with an expanded genetic alphabet". Nature. 509: 385–388. doi:10.1038/nature13314. PMC 4058825

. PMID 24805238. Retrieved May 7, 2014.

. PMID 24805238. Retrieved May 7, 2014. - ↑ Ward; et al. (1969). "Fluorescence Studies of Nucleotides and Polynucleotides I. Formycin 2-Aminopurine Riboside 2,6-Diaminopurine Riboside and Their Derivatives". J. Biol. Chem. 244: 1228–37.

- ↑ Hawkins (2001). "Fluorescent pteridine nucleoside analogs - A window on DNA interactions". Cell Biochem. Biophys. 34: 257–81. doi:10.1385/cbb:34:2:257.

- ↑ Berry; et al. (2004). "Pyrrolo-dC and pyrrolo-C: fluorescent analogs of cytidine and 2 '-deoxycytidine for the study of oligonucleotides". Tetrahedron Lett. 45: 2457–61. doi:10.1016/j.tetlet.2004.01.108.

- ↑ Wojciechowski; et al. (2008). "Fluorescence and hybridization properties of peptide nucleic acid containing a substituted phenylpyrrolo-cytosine designed to engage guanine with an additional H-bond". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130: 12574–12575. doi:10.1021/ja804233g.

- ↑ Greco; et al. (2005). "Simple fluorescent pyrimidine analogues detect the presence of DNA abasic sites". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127: 10784–85. doi:10.1021/ja052000a.

- ↑ Rist; et al. (2002). "Fluorescent nucleotide base analogs as probes of nucleic acid structure, dynamics and interactions". Curr. Org. Chem. 6: 775–93. doi:10.2174/1385272023373914.

- ↑ Wilson; et al. (2006). "Fluorescent DNA base replacements: reporters and sensors for biological systems". Org, & Biomol. Chem. 4: 4265–74. doi:10.1039/b612284c.

- ↑ Wilhelmsson and Tor (2016). Fluorescent Analogs of Biomolecular Building Blocks: Design and Applications. New Jersey: Wiley. ISBN 978-1-118-17586-6.

- ↑ Wilhelmsson (2010). "Fluorescent nucleic acid base analogues". Q. Rev. Biophys. 43 (2): 159–183. doi:10.1017/s0033583510000090.

- ↑ Sinkeldam; et al. (2010). "Fluorescent analogs of Biomolecular Building Blocks: Design, properties and applications". Chem. Rev. 110 (5): 2579–2619. doi:10.1021/cr900301e.

- ↑ Wilhelmsson; et al. (2001). "A highly fluorescent DNA base analogue that forms Watson-Crick base pairs with guanine". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 123: 2434–35. doi:10.1021/ja0025797.

- ↑ Sandin; et al. (2005). "Fluorescent properties of DNA base analogue tC upon incorporation into DNA - negligible influence of neighbouring bases on fluorescence quantum yield". Nucleic Acids Res. 33: 5019–25. doi:10.1093/nar/gki790.

- ↑ Sandin; et al. (2008). "Characterization and use of an unprecedentedly bright and structurally non-perturbing fluorescent DNA base analogue". Nucleic Acids Res. 36: 157–67. doi:10.1093/nar/gkm1006.

- ↑ Börjesson; et al. (2009). "Nucleic acid base analog FRET-pair facilitating detailed structural measurements in nucleic acid containing systems". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131: 4288–93. doi:10.1021/ja806944w.

- 1 2 Rodriguez, Hernandez (2013). "Structural and mechanistic basis for enhanced translational efficiency by 2-thiouridine at the tRNA anticodon wobble position.". J. Mol. Biol. 425: 3888–906. doi:10.1016/j.jmb.2013.05.018. PMC 4521407

. PMID 23727144.

. PMID 23727144. - ↑ Kirnos MD, Khudyakov IY, Alexandrushkina NI, Vanyushin BF. 2-aminoadenine is an adenine substituting for a base in S-2L cyanophage DNA. Nature. 1977 Nov 24;270(5635):369–70.

- ↑ Johnson SC et al. A third base pair for the polymerase chain reaction: inserting isoC and isoG. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004 Mar 29;32(6):1937–41.

- ↑ Taniguchi, Y; Kool, ET (Jul 2007). "Nonpolar isosteres of damaged DNA bases: effective mimicry of mutagenic properties of 8-oxopurines". J Am Chem Soc. 129 (28): 8836–44. doi:10.1021/ja071970q.

- ↑ Hwang, G. T.; Romesberg, F. E. (2008). "Unnatural Substrate Repertoire of A, B, and X Family DNA Polymerases". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130: 14872–14882. doi:10.1021/ja803833h.

- ↑ Kimoto, M; et al. (2007). "Fluorescent probing for RNA molecules by an unnatural base-pair system". Nucleic Acids Res. 35 (16): 5360–9. doi:10.1093/nar/gkm508.

- ↑ Zimmermann, N; et al. (Feb 2004). "A second-generation copper(II)-mediated metallo-DNA-base pair". Bioorg Chem. 32 (1): 13–25. doi:10.1016/j.bioorg.2003.09.001.

- ↑ Liu, H; et al. (2003). "A four-base paired genetic helix with expanded size". Science. 302 (5646): 868–71. doi:10.1126/science.1088334.

- ↑ Wettig, S. D.; Lee, J.S. (2003). J. Inorg. Biochem. 94: 94–99. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Zhang, H.; Calzolari, A.; Felice, R. Di (2005). "On the Magnetic Alignment of Metal Ions in a DNA-Mimic Double Helix". J. Phys. Chem. B. 109: 15345–15348. doi:10.1021/jp052202t.

- ↑ Aich, P.; Skinner, R. J. S.; Wettig, S. D.; Steer, R. P.; Lee, J. S. (2002). Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 20: 93–98. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Clever, G. H.; Polborn, K.; Carell, T. (2005). "Ein hochgradig DNA-Duplex-stabilisierendes Metall-Salen-Basenpaar". Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 117: 7370–7374. doi:10.1002/ange.200501589.

- ↑ Buncel, E.; Boone, C.; Joly, H.; Kumar, R.; Norris, A. R. J. "Inorg. Biochem.". 1985'. 25: 61–73.

- ↑ Ono, A.; Togashi, H. (2004). "Highly Selective Oligonucleotide-Based Sensor for Mercury(II) in Aqueous Solutions". Angew. Chem. 43: 4300–4302. doi:10.1002/anie.200454172.

- ↑ Meggers, E.; Holland, P. L.; Tolman, W. B.; Romesberg, F. E.; Schultz, P. G. "J. Am. Chem. Soc.". 2000'. 122: 10714–10715. doi:10.1021/ja0025806.

- ↑ Lee, J. S.; Skinner, R. J. S.; Latimer, L. J. P.; Reid, R. S. "Biochem. Cell Biol.". 1993'. 71: 162–168. doi:10.1139/o93-026.

- ↑ Tanaka, K.; Tengeiji, A.; Kato, T.; Toyama, N.; Shionoya, M. (2003). "A Discrete Self-Assembled Metal Array in Artificial DNA". Science. 299: 1212–1213. doi:10.1126/science.1080587.

- ↑ Malyshev, Denis A.; Dhami, Kirandeep; Quach, Henry T.; Lavergne, Thomas; Ordoukhanian, Phillip (24 July 2012). "Efficient and sequence-independent replication of DNA containing a third base pair establishes a functional six-letter genetic alphabet". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 109 (30): 12005–12010. Bibcode:2012PNAS..10912005M. doi:10.1073/pnas.1205176109. Retrieved 2014-05-11.

- ↑ Callaway, Ewan (May 7, 2014). "Scientists Create First Living Organism With 'Artificial' DNA". Nature News. Huffington Post. Retrieved 8 May 2014.

- 1 2 Fikes, Bradley J. (May 8, 2014). "Life engineered with expanded genetic code". San Diego Union Tribune. Retrieved 8 May 2014.

- ↑ Sample, Ian (May 7, 2014). "First life forms to pass on artificial DNA engineered by US scientists". The Guardian. Retrieved 8 May 2014.

- ↑ Pollack, Andrew (May 7, 2014). "Scientists Add Letters to DNA's Alphabet, Raising Hope and Fear". New York Times. Retrieved 8 May 2014.

- ↑ Hirao, I.; et al. (2002). "An unnatural base pair for incorporating amino acid analogs into proteins". Nat. Biotechnol. 20: 177–182. doi:10.1038/nbt0202-177.

- ↑ Hirao, I.; et al. (2006). "An unnatural hydrophobic base pair system: site-specific incorporation of nucleotide analogs into DNA and RNA". Nat. Methods. 6: 729–735. doi:10.1038/nmeth915.

- ↑ Kimoto, M.; et al. (2009). "An unnatural base pair system for efficient PCR amplification and functionalization of DNA molecules". Nucleic acids Res. 37: e14. doi:10.1093/nar/gkn956.

- ↑ Yamashige, R.; et al. "Highly specific unnatural base pair systems as a third base pair for PCR amplification". Nucleic Acids Res. 40: 2793–2806. doi:10.1093/nar/gkr1068.

- ↑ Kimoto, M.; et al. (2013). "Generation of high-affinity DNA aptamers using an expanded genetic alphabet". Nat. Biotechnol. 31: 453–457. doi:10.1038/nbt.2556.

- ↑ Schmidt M. Xenobiology: a new form of life as the ultimate biosafety tool Bioessays Vol 32(4):322-331

- ↑ Herdewijn, P; Marlière, P (Jun 2009). "Toward safe genetically modified organisms through the chemical diversification of nucleic acids". Chem Biodivers. 6 (6): 791–808. doi:10.1002/cbdv.200900083.

- ↑ Shinkai, A.; Patel, P. H.; Loeb, L. A. (2001). J Biol. Chem. 276: 18836. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Rackham, O; Chin, JW (Aug 2005). "A network of orthogonal ribosome x mRNA pairs". Nat Chem Biol. 1 (3): 159–66. doi:10.1038/nchembio719.