My Old Kentucky Home

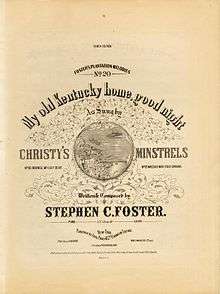

| "My Old Kentucky Home" | |

|---|---|

Sheet music, 10th edition, 1892(?) | |

| Song by Stephen Foster | |

| Published | New York: Firth, Pond & Co. (January 1853) |

| Form | Strophic with chorus |

| Writer(s) | Stephen Foster |

| Language | English |

"My Old Kentucky Home, Good-Night!" is an anti-slavery ballad[1] originally written by Stephen Foster, probably composed in 1852.[2] It was published as in January 1853 by Firth, Pond, & Co. of New York.[2][3] Foster likely composed the song after having been inspired by the narrative of popular anti-slavery novelist Harriet Beecher Stowe's "Uncle Tom's Cabin", while likely referencing imagery witnessed on his visits to the Bardstown, Kentucky farm called Federal Hill.[4] In Foster's sketchbook, the song was originally entitled "Poor Uncle Tom, Good-Night!", but was altered by Foster as "My Old Kentucky Home, Good-Night!" Frederick Douglass, an abolitionist, wrote in his 1855 autobiography My Bondage and My Freedom that the song "awakens sympathies for the slave, in which antislavery principles take root, grow, and flourish".[5][6]

Original lyric synopsis

The storyline in Harriet Beecher Stowe's abolitionist novel Uncle Tom's Cabin, is synonymous with the narrative of the song "My Old Kentucky Home, Good-Night!"

In its entirety, the song contains three verses and one chorus repeated after each verse. The first verse of "My Old Kentucky Home, Good-Night!" describes an enslaved servant's description of the natural beauty and their feelings associated with a Kentucky farm landscape. The line that begins "By'n by Hard Times, comes a knocking at the door, Then my old Kentucky home, good-night!" acknowledges that the farm is experiencing financial hardship, and the verse suggests that the narrator knows they will leave the Kentucky farm as a result of being sold to settle the debt. The chorus of the song describes a presumptive longing by the narrator to return to the Kentucky farm: "Weep no-more my lady, O weep no more today. For we'll sing one song for my old Kentucky home, for my old Kentucky home far-away."

In the second verse, the enslaved servant describes an environment on the Kentucky farm absent of his peers. The narrator recalls a variety of remembrances of his peers and the places they formerly occupied, "They sing no more by the glimmer of the moon, On the bench by the old cabin door."

In the third verse, the narrator outlines that the work of an enslaved servant is unavoidable and exhausting regardless of location, "The head must bow and the back will have to bend, Wherever the darkies may go". The narrator acknowledges in the third line of the third verse that they have been sold to a sugar plantation and that they will likely perish as a result. In the fifth line of the third verse, the narrator observes that their departure from the Kentucky farm will occur in a matter of days and again refrains that an enslaved servant's work is highly strenuous, "A few more days for to tote the weary load, no matter, 'twill never be light".

The song ends with the chorus which contextually applies to all three verses. Throughout its composition, the song's narrator remains non-gender specific. Foster's composition, both in each verse and in its entirety, focuses on the unfair treatment of slaves and serves to bring awareness to its listeners of the hardships endured by slaves. The composition also embodies a common theme in Foster's work of Foster's own childhood experiences of losing his home as a result of financial hardships.[7]

Creation and career impact

The creation of the song "My Old Kentucky Home, Good-Night!" established a decisive moment within Stephen Foster's career in regards to his personal beliefs on the institution of slavery and is an example of the common theme of the loss of home, which is prevalent throughout Foster's work. In March 1852, Harriet Beecher Stowe's abolitionist novel Uncle Tom's Cabin appeared in bookstores in Foster's home town of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. The novel, written about the plight of an enslaved servant in Kentucky, greatly impacted Foster's future work in song-writing by altering the tone of his music to sympathize the position of the enslaved servant. In his notebook, Foster penned the lyrics inspired by Stowe's novel, initially named "Poor Old Uncle Tom, Good-Night!" with distinct Kentucky imagery that according to Foster's brother Morrison, was inspired by what Foster had seen during visits to the Federal Hill farm owned by Foster's cousins the Rowan family of Bardstown, Kentucky. Foster ultimately removed references to Stowe's book, renaming the work, "My Old Kentucky Home, Good-Night!"

The song "My Old Kentucky Home, Good-Night!" is one of many examples of the loss of home in Foster's work. Biographers believe that this common theme originated from the loss of Foster's childhood home, known as the "White Cottage", an estate his mother referred to as an Eden, in reference to the Garden of Eden. The family was financially supported largely by the family patriarch William Foster, who owned vast holdings, which were lost through bad business dealings that left the family destitute and unable to keep possession of the White Cottage. The Foster family was forced to leave the estate when Stephen Foster was three years old. After years of financial instability and recounts of fond memories of the White Cottage shared with Stephen by his parents and siblings, the impact of longing for a permanent home that was no longer available to Stephen greatly influenced his writing with deep impulses for the nostalgia of home.[7]

Public sentiment

Upon its release in 1853 by Firth, Pond & Company,[8] "My Old Kentucky Home, Good-Night" grew quickly in popularity, selling thousands of copies. The song's popular and nostalgic theme of the loss of home resonated with the public and further resolved to stimulate strong feelings in support of the abolitionist movement in the United States. Famous African-American abolitionist Frederick Douglass promoted the song, among other similar songs of the time period, in his autobiography, My Bondage and My Freedom as evoking a sentimental theme towards the enslaved servant that promotes and popularizes the cause of abolishing slavery in the United States. Douglass commented, "They [My Old Kentucky Home, Good-Night!, etc.] are heart songs, and the finest feelings of human nature are expressed in them. [They] can make the heart sad as well as merry, and can call forth a tear as well as a smile. They awaken the sympathies for the slave", he stated, "in which anti-slavery principles take root and flourish".[9]

The song held popularity for over a decade and throughout the American Civil War. The song's reach throughout the United States and popularity has been attributed to soldiers of the war, who passed the tune from location to location during the war's tenure. Soldiers of the war, both Union and Confederate, visited Federal Hill by the thousands to see the landmark that lent visual inspiration for Foster's song both during the war and after. After the war, Federal Hill continued to be frequented by tourists throughout the remainder of the 19th century.[10]

After the American Civil War had ended and the institution of slavery was abolished, the song, "My Old Kentucky Home, Good Night!", which encouraged and inspired abolitionist views in the United States thereafter continued to be held in high esteem by the public. The typical reduction of the song's title from "My Old Kentucky Home, Good-Night!" to "My Old Kentucky Home" occurred after the turn of the century.[11]

The song's first verse and chorus are recited annually at the Kentucky Derby. As early as 1930, it was played to accompany the Post Parade; the University of Louisville Marching Band has played the song for all but a few years since 1936. In 1982, Churchill Downs honored Foster by establishing the Stephen Foster Handicap.[12] The University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, Murray State University, Eastern Kentucky University, and Western Kentucky University bands play the song at their schools' football and basketball games.[13]

Kentucky state song

WHEREAS, the song, "My Old Kentucky Home," by Stephen Collins Foster, has immortalized Kentucky throughout the civilized world, and is known and sung in every State and Nation; ...

— Preamble to a 1928 Act of the Kentucky legislature[14]

In 1928, "My Old Kentucky Home" was "selected and adopted" by the Kentucky state legislature as the state's official song.[15] It has remained so, subject to one change that was made in 1986. In that year, a Japanese youth group visiting the Kentucky General Assembly sang the song to the legislators, using the original lyrics that included the word "darkies". Carl Hines, at the time the only African-American member of the state's House of Representatives, was offended by this and subsequently introduced a resolution that would substitute the word "people" in place of "darkies" whenever the song was used by the House of Representatives. A similar resolution was introduced by Georgia Davis Powers in the Kentucky State Senate. The resolution was adopted by both chambers.[16]

Modern impact

Today, the song My Old Kentucky Home remains an important composition due to its role in the evolution of American songwriting and as one of the most influential songs in American culture. According to popular-song analysts, the appeal of the theme of 'returning home' is one in which listeners of "My Old Kentucky Home" are able to personally relate within their own lives. Many revisions and updates of the song have occurred throughout the past century has further ingrained the song in American culture.[7]

Recording history

"My Old Kentucky Home" was recorded many times during the early era of cylinder recordings. The Cylinder Audio Archive at the University of California (Santa Barbara) Library contains nineteen commercial recordings of the song (in addition to several home recordings).[17] In most cases, even those of the commercial recordings, the Archive is unable to determine the precise dates (or even years) of either their recording or their release, with some cylinders being dated only to a forty-year range from the 1890s to the 1920s. The earliest recording of "My Old Kentucky Home" for which the Archive was able to determine a precise year of release is from 1898 and features an unidentified cornet duo.[18] However, the song is known to have been recorded earlier than that (in February 1894) by the Standard Quartette, a vocal group that was appearing in a musical that featured the song (making their recording perhaps the earliest example of a cast recording). No copy of that cylinder is known to have survived.[19] And although cylinder recordings were more popular during the 1800s than were disc records, some of the latter were being sold, mostly by Berliner Gramophone. A version sung by A.C. Weaver was recorded in September 1894 and released with catalog number 175.[20]

The popularity of "My Old Kentucky Home" as recording material continued into the 20th century, despite the fact that the song was then more than fifty years old. In the first two decades of the century, newly established Victor Records released thirteen versions of the song (plus five more recordings that included it as part of a medley).[21] During that same period, Columbia Records issued a similar number, including one by Margaret Wilson (daughter of U.S. president Woodrow Wilson).[22] One of the major vocal groups of the day, the Peerless Quartet, recorded it twice,[23] as did internationally-known operatic soprano Alma Gluck.[24] It was also recorded by various marching and concert bands, including three recordings by one of the most well-known, Sousa's Band,[25] as well as three by the house concert band at Edison Records.[26]

Although the frequency of its recording dropped off as the century progressed, "My Old Kentucky Home" continued to be used as material by some of the major popular singers of the day. Versions were recorded by Kate Smith,[27] Bing Crosby,[28] and Al Jolson.[29] A version by operatic contralto Marian Anderson was released in Japan[30] and Paul Robeson recorded his version for an English company while living in London in the late 1920s.[31] The song continued to find expression in non-traditional forms, including a New Orleans jazz version by Louis Armstrong[32] and a swing version by Gene Krupa.[33] For a listing of some other recorded versions of the song, see External links.

In 2001, the National Endowment for the Arts and the Recording Industry Association of America promulgated a list of the 365 "Songs of the Century" that best displayed "historical significance of not only the song, but also of the record and artist".[34] "My Old Kentucky Home" appeared on that list (the only song written by Foster to do so), represented by the 1908 recording of operatic soprano Geraldine Farrar (Victor Records 88238).

Adaptations

By the time that commercial music began to be recorded, the verse melody of "My Old Kentucky Home" had become so widely known that recording artists sometimes quoted it in material that was otherwise unrelated to Foster's song. Henry Burr's 1921 recording of "Kentucky Home" quotes the melody in an interlude midway through the record.[35] And vaudeville singer Billy Murray's 1923 recording of "Happy and Go-Lucky in My Old Kentucky Home" adds the melody in the record's finale.[36] An earlier recording by Murray, 1915's "We'll Have a Jubilee in My Old Kentucky Home", takes the further step of incorporating a portion of Foster's melody (but not his lyrics) into each chorus.[37] And a few decades earlier than that, a young Charles Ives, while still a student at Yale University in the 1890s, used Foster's melody (both the verse and the chorus) as a strain in one of his marches. Ives often quoted from Foster and musicologist Clayton Henderson has detected material from "My Old Kentucky Home" in eight other of his works.[38]

In the mid 1960s, songwriter Randy Newman used the verse of "My Old Kentucky Home" (with modified lyrics) as the chorus to his "Turpentine and Dandelion Wine". Newman recorded this adaptation for his 12 Songs album (1970, Reprise RS 6373) under the title "Old Kentucky Home". However, the adaptation had been recorded earlier at least twice. The first was by the Beau Brummels, who recorded it for their Triangle album (1967, Warner Brothers WS 1692). The second was by the Alan Price Set, who included it as the B-side to their "Love Story" single (1968, Decca F 12808). Since Newman's recording, the adaptation was covered several times more. The only version that charted was by Johnny Cash, who released it as a single from his John R. Cash album (1975, Columbia KC 33370). The single reached No. 42 on Billboard's country-music chart.[39] Note that the various cover versions generally use slightly different titles, some adding "My" to Newman's title, others omitting "Old". Also, some use Newman's original title of "Turpentine and Dandelion Wine" as a subtitle. A more-complete listing of these cover versions can be found in External links.

Appearance in media

"My Old Kentucky Home" has appeared in many films, live action and animated, and in television episodes, in the 20th and 21st centuries.

In 1926, the song first appeared in film in the first animated cartoon to have ever featured synchronized dialogue.[40]

The original title for the first draft of Margaret Mitchell's 1936 novel Gone with the Wind was "Tote The Weary Load", a lyric from "My Old Kentucky Home, Good-Night!"[41] The lyric "a few more days for to tote the weary load" appears in the text of the novel as Scarlett O'Hara is returning to Tara.[42]

Judy Garland sang "My Old Kentucky Home, Good-Night!" live on December 14, 1938 on the radio show, America Calling. She later covered it again on The All Time Flop Parade with Bing Crosby and The Andrews Sisters. On April 29, 1953, Garland headlined a Kentucky Derby week appearance in Lexington, Kentucky named "The Bluegrass Festival" where she sang the song "My Old Kentucky Home", accompanied by a single violin.[43]

In 1939, "My Old Kentucky Home" was featured in the film version of Gone With The Wind both instrumentally and with lyrics. In the movie, Prissy, played by Butterfly McQueen, sings the line, "a few more days for to tote the weary load".[44]

In 1940, Bing Crosby sung "My Old Kentucky Home, Good-Night!" via radio broadcast with Leopold Stokowski conducting a symphony for the dedication of the Stephen Foster postage stamp release held in Bardstown, Kentucky at My Old Kentucky Home.[45]

Kate Smith performed the song on March 20, 1969 on The Dean Martin Show with Mickey Rooney and Barbara Eden.[46][47]

Johnny Depp, Lyle Lovett, David Amram and Warren Zevon covered the song "My Old Kentucky Home" at the tribute memorial of journalist Hunter Thompson in December 1996. One of Thompson's most notable pieces, "The Kentucky Derby Is Decadent and Depraved", in addition to Thompson being a native of Louisville, Kentucky, inspired the artists to cover the song for his tribute. The performance was recreated 9 years later in 2005 at midnight after Thompson's ashes were blasted from a cannon.[48]

Lyrics by Stephen Foster

The original Stephen Foster lyrics of the song, were:

|

The sun shines bright in the old Kentucky home. |

Weep no more my lady, oh! weep no more today! |

Most modern renditions of the song change the word "darkies" to "people".

References

- ↑ "My Old Kentucky Home: A Song with a Checkered Past". studio360. Retrieved July 10, 2015.

- 1 2 Richard Jackson (1974). Stephen Foster song book: original sheet music of 40 songs. Courier Dover Press. p. 177.

- ↑ "My Old Kentucky Home, Good Night!". 2008. Retrieved October 1, 2016.

- ↑ "My Old Kentucky Home State Park » The History of My Old Kentucky Home". visitmyoldkyhome.com. Retrieved July 10, 2015.

- ↑ PressRoom (April 9, 2001). "American Experience on KET profiles "My Old Kentucky Home" author, Stephen Foster". KET. Retrieved July 11, 2011.

- ↑ Douglass, Frederick. My Bondage and My Freedom: Part I- Life as a Slave, Part II- Life as a Freeman, with an introduction by James M'Cune Smith. New York and Auburn: Miller, Orton & Mulligan (1855); ed. John Stauffer, Random House (2003) ISBN 0-8129-7031-4.

- 1 2 3 MacLowry, Randall. "American Experience, Stephen Foster". PBS.org. Public Broadcasting System. Retrieved December 23, 2015.

- ↑ William Emmett Studwell (1997). The Americana song reader. Psychology Press. p. 110.

- ↑ Douglass, Frederick (1855). My Bondage, My Freedom. Miller, Orton & Mulligan. p. 462. Retrieved January 25, 2016.

- ↑ "History - My Old Kentucky Home - Recreation Parks - Kentucky State Parks". ky.gov. Retrieved July 10, 2015.

- ↑ Clark, Thomas D. (February 5, 2015) [1977]. "The Slavery Background of Foster's My Old Kentucky Home". In Harrison, Lowell H.; Dawson, Nelson L. A Kentucky Sampler: Essays from The Filson Club History Quarterly 1926–1976. Lexington, Kentucky: University Press of Kentucky. pp. 100–117. ISBN 9780813163086. Retrieved January 25, 2016.

- ↑ "My Old Kentucky Home: Official Song of the Kentucky Derby". Retrieved October 1, 2016.

- ↑ Kaiser, Carly (May 4, 2011). "My Old Kentucky Home". University Place Patch. Retrieved October 1, 2016.

- ↑ Shankle, George Earlie (1941) [1934]. State Names, Flags, Seals, Songs, Birds, Flowers, and Other Symbols (revised ed.). New York: H.W. Wilson. pp. 397–398.

- ↑ When originally enacted, the provision was located at section 4618p of the Kentucky Statutes. After the re-codification of those Statutes in 1942, the provision now resides at section 2.100 of Title I, Chapter 2 of the Kentucky Revised Statutes.

- ↑ "Interview with Carl R. Hines, Sr.,". Louie B. Nunn Center for Oral History. University of Kentucky Libraries: Lexington. Retrieved June 18, 2016. Discussion of the episode begins approximately 82 minutes into the interview. Also see the contemporaneous reporting that appeared in the article written by Bob Johnson in the edition of March 12, 1986 of the Courier-Journal (page 18) and the Associated Press article that appeared in the edition of March 21, 1986 of the Lexington Herald-Leader (page A11). Hines' resolution was House Resolution 159 (1986); Powers' resolution was Senate Resolution 114 (1986).

- ↑ "Search Results: my+old+kentucky+home". UCSB Cylinder Audio Archive. UC Santa Barbara Library. Retrieved June 2, 2016.

- ↑ Columbia Phonograph Company 2813 (cylinder 14763 at the Cylinder Audio Archive).

- ↑ Brooks, Tim (2004). Lost Sounds: Blacks and the Birth of the Recording Industry, 1890-1919. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0-252-02850-3. The Standard Quartette is discussed in Chapter 6 (pages 92-102). The February 1894 recordings are discussed at pages 95-97.

- ↑ "Berliner 175 (7-in. single-faced)". Discography of American Historical Recordings. UC Santa Barbara Library. Retrieved June 2, 2016. Note that Berliner issued "My Old Kentucky Home" several times through 1899, with different singers. These re-recordings were released under the same catalog number as the original, but with differently-suffixed matrix numbers. For example, the version sung by Weaver has matrix number 175-Z, whereas a later version by Irish tenor George J. Gaskin (recorded in 1897) has matrix number 175-ZZ.

- ↑ "Search Results: my+old+kentucky+home". National Jukebox. Library of Congress. Retrieved June 3, 2016.

- ↑ Columbia Records ("Symphony Series") A-2416 (1917)

- ↑ Indestructible Records 694 (1908) and Everlasting Records 1077 (1909)

- ↑ Victor Records 74386 (1914) and 74468 (1916).

- ↑ Berliner 129 (1898), Victor 3264 (1901) and Victor 2481 (1903). The two Victor recordings were labeled "fantasies".

- ↑ Edison Gold Moulded 8818 (1904), Edison Amberol 87 (1909), and Edison Blue Amberol 2239 (1914), all credited to the Edison Concert Band.

- ↑ MGM Records 30474, part of Smith's Songs of Stephen Foster album (MGM E-106)

- ↑ Crosby's recording appeared as the B-side on two of his singles—"'Til Reveille" (Decca Records 3886, 1941) and "De Camptown Races" (Decca Records 25129, 1947). It also appeared in his Stephen Foster album (Decca Records A-440 and A-482, both 1946).

- ↑ Decca Records 27365 (circa 1950)

- ↑ Victor Co. of Japan SD-4. This is the same recording that was released by Victor Records in the United States with catalog number 18314. The recording and release dates are unclear, but the physical characteristics of the label for the Japanese release (red label, circular non-scroll border, etc.), as well as the numbering of the American release, suggest that both were issued in the very early 1940s (and certainly before the outbreak of war between Japan and the United States). The recording later appeared on the 1951 LP Great Combinations (RCA Victor LM 1703).

- ↑ His Master's Voice B.3653. The recording's entry at the British Library gives the recording date as October 2, 1928 (see item number BLLSA4329674 at www.explore.bl.uk).

- ↑ On the album Satchmo Plays King Oliver (Audio Fidelity Records AFSD 5930, 1960)

- ↑ Columbia Records 35205 (1939)

- ↑ "RIAA, NEA Announce Songs of the Century" (Press release). Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA). March 2001. Archived from the original on March 24, 2012. Retrieved March 3, 2013.

- ↑ Victor Records 18821. Written by Harold Weeks and Abe Brashen.

- ↑ Victor Records 19240. Written by Clarence Gaskill. Another version of "Happy and Go-Lucky ..." was recorded a few months later by The Happiness Boys, who extended Murray's arrangement by quoting "My Old Kentucky Home" as a countermelody not just in the finale, but also in other parts of the song. That version was issued on Federal Records 5376 (the company not to be confused with the Cincinnati-based Federal Records that operated in the 1950s). It was also issued on Sears, Roebuck's Silvertone label, with catalog number 2376.

- ↑ Edison Blue Amberol Records 2748. Written by Walter Donaldson.

- ↑ Henderson, Clayton W. (2008) [1990]. The Charles Ives Tunebook (second ed.). Bloomington: Indiana University Press. pp. 158–159. ISBN 978-0-253-35090-9. The march is identified as Ives' third (i.e., "March No.3"). It apparently had not been recorded until 1974, when it appeared on the Yale Theater Orchestra's Old Songs Deranged (Columbia Masterworks M 32969). Because Ives added the Foster quote to a work he had already composed, there are two versions of that march—one that incorporates the melody and one that does not. The version that incorporates the melody also appears on the Detroit Chamber Winds' 1993 album Remembrance: A Charles Ives Collection (Koch International Classics 7182).

- ↑ "John R. Cash (awards)". AllMusic.com. Retrieved May 8, 2016.

- ↑ "Silent Era". www.silentera.com. Retrieved April 13, 2016.

- ↑ Horwitz, Tony (1999). Confederates in the Attic. Random House. p. 306. ISBN 9780679758334. Retrieved June 23, 2016.

- ↑ Mitchell, Margaret. Gone with the Wind. 1936. Edition: Hamilton Books, 2016. GoogleBooks pt.258.

- ↑ Schechter, Scott (2006). Judy Garland: The Day-by-Day Chronicle of a Legend. Taylor Trade Publishing. p. 448. ISBN 978-1-4616-3555-0.

- ↑ Edge, Lynn (October 8, 1989). "'GWTW' start toted the load during filming" (60). Star-News. Retrieved May 9, 2016.

- ↑ Hibbs, Dixie (198). Bardstown. Bardstown, Kentucky: Arcadia. p. 78. ISBN 9780738589916. Retrieved June 23, 2016.

- ↑ Eden, Barbara (April 5, 2011). Jeanie Out of the Bottle. Random House. ISBN 9780307886958. Retrieved May 9, 2016.

- ↑ "Bundle Up With Dean". The Golddiggers. The Golddiggers. Retrieved May 9, 2016.

- ↑ "Amram with Johnny Depp, Warren Zevon: Hunter S. Thompson Tribute". Youtube. Retrieved April 16, 2016.

Further reading

- Clark, Thomas D. (January 1936). "The Slavery Background of Foster's My Old Kentucky Home". Filson Club History Quarterly. 10 (1). ISBN 9780813163086. Retrieved November 29, 2011.

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Performances

- My Old Kentucky Home (instrumental) as played by one of the University of Kentucky Bands

- Geraldine Farrar's 1908 recording

- Other

- List of recordings of "My Old Kentucky Home" at SecondHandSongs.com

- List of recordings of Randy Newman's adaptation at SecondHandSongs.com