Gone with the Wind (novel)

First edition cover | |

| Author | Margaret Mitchell |

|---|---|

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Historical Fiction |

| Publisher | Macmillan Publishers |

Publication date | June 30, 1936[1] |

| Media type | Print (hardback & paperback) |

| Pages |

1037 (first edition) 1024 (Warner Books paperback) |

| ISBN | 978-0-446-36538-3 (Warner) |

| OCLC | 28491920 |

| 813.52 | |

| Followed by |

Scarlett Rhett Butler's People |

Gone with the Wind is a novel written by Margaret Mitchell, first published in 1936. The story is set in Clayton County and Atlanta, both in Georgia, during the American Civil War and Reconstruction Era. It depicts the struggles of young Scarlett O'Hara, the spoiled daughter of a well-to-do plantation owner, who must use every means at her disposal to claw her way out of poverty following the destructive Sherman's March to the Sea. This historical novel features a Bildungsroman or coming-of-age story, with the title taken from a poem written by Ernest Dowson.

Gone with the Wind was popular with American readers from the outset and was the top American fiction bestseller in the year it was published and in 1937. As of 2014, a Harris poll found it to be the second favorite book of American readers, just behind the Bible. More than 30 million copies have been printed worldwide.

Written from the perspective of the slaveholder, Gone with the Wind is Southern plantation fiction. Its portrayal of slavery and African Americans has been considered controversial, especially by succeeding generations, as well as its use of a racial epithet and ethnic slurs common to the period. However, the novel has become a reference point for subsequent writers about the South, both black and white. Scholars at American universities refer to it in their writings, interpret and study it. The novel has been absorbed into American popular culture.

Mitchell received the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction for the book in 1937. It was adapted into a 1939 American film. The book is often read or misread through the film. Gone with the Wind is the only novel by Mitchell published during her lifetime.[2]

Mitchell used color symbolism, especially the colors red and green, which frequently are associated with Scarlett O'Hara. Mitchell identified the primary theme as survival. She left the ending speculative for the reader, however. She was often asked what became of her lovers, Rhett and Scarlett. She replied, "For all I know, Rhett may have found someone else who was less difficult."[3] Two sequels authorized by Mitchell's estate were published more than a half century later. A parody was also produced.

Biographical background and publication

Born in 1900 in Atlanta, Georgia, Margaret Mitchell was a Southerner and writer throughout her life. She grew up hearing stories about the American Civil War and the Reconstruction from her tyrannical Irish-American grandmother, who had endured its suffering. Her forceful and intellectual mother was a suffragist who fought for the rights of women to vote.

As a young woman, Mitchell found love with an army lieutenant who was killed in World War I, and she would carry his memory for the remainder of her life. After studying at Smith College for a year, during which time her mother died from the Spanish flu, Mitchell returned to Atlanta. She married, but her husband was an abusive bootlegger. Mitchell took a job writing feature articles for the Atlanta Journal at a time when Atlanta debutantes of her class did not work. After divorcing her first husband, she married again, this time to a man who shared her interest in writing and literature.

Margaret Mitchell began writing Gone with the Wind in 1926 to pass the time while recovering from a slow-healing auto-crash injury.[3] In April 1935, Harold Latham of Macmillan, an editor looking for new fiction, read her manuscript and saw that it could be a best-seller. After Latham had agreed to publish the book, Mitchell worked for another six months checking the historical references and rewriting the opening chapter several times.[4] Mitchell and her husband John Marsh, a copy editor by trade, edited the final version of the novel. Mitchell wrote the book's final moments first and then wrote the events that led up to these.[5] Gone with the Wind was published in June 1936.

Title

The author tentatively titled the novel Tomorrow is Another Day, from its last line.[6] Other proposed titles included Bugles Sang True, Not in Our Stars, and Tote the Weary Load.[4] The title Mitchell finally chose is from the first line of the third stanza of the poem "Non Sum Qualis Eram Bonae sub Regno Cynarae" by Ernest Dowson:

I have forgot much, Cynara! gone with the wind,

Flung roses, roses riotously with the throng,

Dancing, to put thy pale, lost lilies out of mind...[7]

Scarlett O'Hara uses the title phrase when she wonders to herself if her home on a plantation called "Tara" is still standing, or if it is "gone with the wind which had swept through Georgia."[8] In a general sense, the title is a metaphor for the departure of a way of life in the South prior to the Civil War. When taken in the context of Dowson's poem about "Cynara," the phrase "gone with the wind" alludes to erotic loss.[9] The poem expresses the regrets of someone who has lost his passionate feelings for his "old passion," Cynara.[10] Dowson's Cynara, a name that comes from the Greek word for artichoke, represents a lost love.[11]

The title was printed throughout the 1,037 pages of the book as shown here: Gone with the Wind, using lower-case letters for the words with and the. An upper-case W for the word with appeared in the title printed on the dust jacket where the words GONE, WITH and WIND were in capital letters in brown ink against a yellow background (GONE WITH the WIND), giving the title a billboard-like presentation. The title was printed in all capitals, partially italicized, on two lines in blue ink: GONE (first line), WITH THE WIND (second line), on the hardcover, which was "Confederate gray".[12]

Plot summary

Gone with the Wind takes place in the southern United States in the state of Georgia during the American Civil War (1861–1865) and the Reconstruction Era (1865–1877). The novel unfolds against the backdrop of rebellion wherein seven southern states initially, Georgia among them, have declared their secession from the United States (the "Union") and formed the Confederate States of America (the "Confederacy"), after Abraham Lincoln was elected president. The Union refuses to accept secession and no compromise is found as war approaches.

Part I

The novel opens in April 1861 at "Tara," a plantation owned by Gerald O'Hara, an Irish immigrant who has become a successful planter, and his wife, Ellen Robillard O'Hara, from a coastal aristocratic family of French Huguenot descent. Their 16-year-old daughter, Scarlett, is not beautiful, but men seldom realized it once they were caught up in her charm.[13] It was the day before the men were called to war, Fort Sumter having been fired on two days earlier.

There are brief but vivid descriptions of the South as it began and grew, with backgrounds of the main characters: the stylish and highbrow French, the gentlemanly English, the forced-to-flee and looked-down-upon Irish. Scarlett learns that one of her many beaux, Ashley Wilkes, will soon be engaged to his cousin, Melanie Hamilton. She is heart-stricken. The next day at the Wilkeses' barbecue at Twelve Oaks, Scarlett tells Ashley she loves him, and he admits he cares for her.[14] However, he knows he would not be happy if married to her because of their personality differences. She loses her temper at him, and he silently takes it.

Rhett Butler, who has a reputation as a rogue, had been alone in the library when Ashley and Scarlett entered and felt it wiser to stay unseen during the argument. Rhett applauds Scarlett for the "unladylike" spirit she displayed with Ashley. Infuriated and humiliated, she tells Rhett, "You aren't fit to wipe his boots!"[14]

After rejoining the other party guests, she learns that war has been declared and the men are going to enlist. Seeking revenge, Scarlett accepts a marriage proposal from Melanie's brother, Charles Hamilton. They marry two weeks later. Charles dies of pneumonia following the measles two months after the war begins. As a young widow, Scarlet gives birth to her first child, Wade Hampton Hamilton, named after his father's general.[15] She is bound by custom to wear black and avoid conversation with young men. Scarlett feels restricted by these conventions and bitterly misses her life as a young, unmarried woman.

Part II

Aunt Pittypat is living with Melanie in Atlanta and invites Scarlett to stay with them. In Atlanta, Scarlett's spirits revive, and she is busy with hospital work and sewing circles for the Confederate Army. Scarlett encounters Rhett Butler again at a benefit dance, where he is dressed like a dandy.[16] Although Rhett believes the war is a lost cause, he is blockade running for profit. The men must bid for a dance with a lady, and Rhett bids "one hundred fifty dollars-in gold"[16] for a dance with Scarlett. They waltz to the tune of "When This Cruel War is Over," and Scarlett sings the words.[16][17][18]Others at the dance were shocked that Rhett would bid for a widow and that she would accept the dance while still wearing black (or widow's weeds). Melanie defends her, saying she is supporting the cause for which Melanie's husband, Ashley, is fighting.

At Christmas (1863), Ashley is granted a furlough from the army. Melanie becomes pregnant with their first child.

Part III

The war is going badly for the Confederacy. By September 1864 Atlanta is besieged from three sides.[19] The city becomes desperate and hundreds of wounded Confederate soldiers pour in. Melanie goes into labor with only the inexperienced Scarlett to assist, as all the doctors are attending the soldiers. Prissy, a young slave, cries out in despair and fear, "De Yankees is comin!"[20] In the chaos, Scarlett, left to fend for herself, cries for the comfort and safety of her mother and Tara. The tattered Confederate States Army sets flame to Atlanta and abandons it to the Union Army.

Melanie gives birth to a boy, Beau, with Scarlett's assistance. Scarlett then finds Rhett and begs him to take herself, Wade, Melanie, Beau, and Prissy to Tara. Rhett laughs at the idea but steals an emaciated horse and a small wagon, and they follow the retreating army out of Atlanta.

Part way to Tara, Rhett has a change of heart and abandons Scarlett to enlist in the army (he later recounts that when they learned he had attended West Point, they put him in the artillery, which may have saved his life). Scarlett then makes her way to Tara, where she is welcomed on the steps by her father, Gerald. Things have drastically changed: Scarlett's mother is dead, her father has lost his mind with grief, her sisters are sick with typhoid fever, the field slaves left after Emancipation, the Yankees have burned all the cotton, and there is no food in the house. Scarlett avows that she and her family will survive and never be hungry again.

The long tiring struggle for survival begins that has Scarlett working in the fields. There are hungry people to feed and little food. There is the ever-present threat of the Yankees who steal and burn. At one point, a Yankee soldier trespasses on Tara, and it is implied that he would steal from the house and possibly rape Scarlett and Melanie. Scarlett kills him with Charles's pistol, and sees that Melanie had also prepared to fight him with a sword.

A long post-war succession of Confederate soldiers returning home stop at Tara to find food and rest. Eventually Ashley returns from the war, with his idealistic view of the world shattered.

Part IV

Life at Tara slowly begins to recover when new taxes are levied on the plantation. Scarlett knows only one man with enough money to help her: Rhett Butler. She looks for him in Atlanta only to learn he is in jail. Rhett refuses to give money to Scarlett, and leaving the jailhouse in fury, she runs into Frank Kennedy, who runs a store in Atlanta and is betrothed to Scarlett's sister, Suellen. Realizing Frank also has money, Scarlett hatches a plot and tells Frank that Suellen will not marry him. Frank succumbs to Scarlett's charms and he marries her two weeks later knowing he has done "something romantic and exciting for the first time in his life."[21] Always wanting her to be happy and radiant, Frank gives Scarlett the money to pay the taxes.

While Frank has a cold and is pampered by Aunt Pittypat, Scarlett goes over the accounts at Frank's store and finds that many owe him money. Scarlett is now terrified about the taxes and decides money, a lot of it, is needed. She takes control of the store, and her business practices leave many Atlantans resentful of her. With a loan from Rhett she buys a sawmill and runs it herself, all scandalous conduct. To Frank's relief, Scarlett learns she is pregnant, which curtails her "unladylike" activities for a while. She convinces Ashley to come to Atlanta and manages the mill, all the while still in love with him. At Melanie's urging, Ashley takes the job. Melanie becomes the center of Atlanta society, and Scarlett gives birth to Ella Lorena: "Ella for her grandmother Ellen, and Lorena because it was the most fashionable name of the day for girls."[22]

Georgia is under martial law, and life has taken on a new and more frightening tone. For protection, Scarlett keeps Frank's pistol tucked in the upholstery of the buggy. Her trips alone to and from the mill take her past a shantytown where criminal elements live. While on her way home one evening, she is accosted by two men who try to rob her, but she escapes with the help of Big Sam, the former Negro foreman from Tara. Attempting to avenge his wife, Frank and the Ku Klux Klan raid the shantytown whereupon Frank is shot dead. Scarlett is a widow again.

To keep the raiders from being arrested, Rhett puts on a charade. He walks into the Wilkeses' home with Hugh Elsing and Ashley, singing and pretending to be drunk. Yankee officers outside question Rhett, and he says he and the other men had been at Belle Watling's brothel that evening, a story Belle later confirms to the officers. The men are indebted to Rhett, and his Scallawag reputation among them improves a notch, but the men's wives, except Melanie, are livid at owing their husbands' lives to Belle Watling.

Frank Kennedy lies in a casket in the quiet stillness of the parlor in Aunt Pittypat's home. Scarlett is remorseful. She is swigging brandy from Aunt Pitty's swoon bottle when Rhett comes to call. She tells him tearfully, "I'm afraid I'll die and go to hell." He says, "Maybe there isn't a hell."[23] Before she can cry any further, he asks her to marry him, saying, "I always intended having you, one way or another."[23] She says she doesn't love him and doesn't want to be married again. However, he kisses her passionately, and in the heat of the moment she agrees to marry him. One year later, Scarlett and Rhett announce their engagement, which becomes the talk of the town.

Part V

Mr. and Mrs. Butler honeymoon in New Orleans, spending lavishly. Upon returning to Atlanta, they stay in the bridal suite at the National Hotel while their new home on Peachtree Street is being built. Scarlett chooses a modern Swiss chalet style home like the one she saw in Harper's Weekly, with red wallpaper, thick red carpet, and black walnut furniture. Rhett describes it as an "architectural horror".[24] Shortly after they move into their new home, the sardonic jabs between them turn into full-blown quarrels. Scarlett wonders why Rhett married her. Then "with real hate in her eyes",[24] she tells Rhett she will have a baby, which she does not want.

Wade is seven years old in 1869 when his half-sister, Eugenie Victoria, named after two queens, is born. She has blue eyes like Gerald O'Hara, and Melanie nicknames her, "Bonnie Blue," in reference to the Bonnie Blue Flag of the Confederacy.

When Scarlett is feeling well again, she makes a trip to the mill and talks to Ashley, who is alone in the office. In their conversation, she comes away believing Ashley still loves her and is jealous of her intimate relations with Rhett, which excites her. She returns home and tells Rhett she does not want more children. From then on, they sleep separately, and when Bonnie is two years old, she sleeps in a little bed beside Rhett (with the light on all night because she is afraid of the dark). Rhett turns his attention toward Bonnie, dotes on her, spoils her, and worries about her reputation when she is older.

Melanie is giving a surprise birthday party for Ashley. Scarlett goes to the mill to keep Ashley there until party time, a rare opportunity for her to see him alone. When she sees him, she feels "sixteen again, a little breathless and excited."[25] Ashley tells her how pretty she looks, and they reminisce about the days when they were young and talk about their lives now. Suddenly Scarlett's eyes fill with tears, and Ashley holds her head against his chest. Ashley sees his sister, India Wilkes, standing in the doorway. Before the party has even begun, a rumor of an affair between Ashley and Scarlett spreads, and Rhett and Melanie hear it. Melanie refuses to accept any criticism of her sister-in-law, and India Wilkes is banished from the Wilkeses' home for it, causing a rift in the family.

Rhett, more drunk than Scarlett has ever seen him, returns home from the party long after Scarlett. His eyes are bloodshot, and his mood is dark and violent. He enjoins Scarlett to drink with him. Not wanting him to know she is fearful of him, she throws back a drink and gets up from her chair to go back to her bedroom. He stops her and pins her shoulders to the wall. She tells him he is jealous of Ashley, and Rhett accuses her of "crying for the moon"[26] over Ashley. He tells her they could have been happy together saying, "for I loved you and I know you."[26] He then takes her in his arms and carries her up the stairs to her bedroom, where it is strongly implied that he rapes her -- or, possibly, that they have consensual sex following the argument.

Next morning Rhett leaves for Charleston and New Orleans with Bonnie. Scarlett finds herself missing him, but she is still unsure if Rhett loves her, having said it while drunk. She learns she is pregnant with her fourth child.

When Rhett returns, Scarlett waits for him at the top of the stairs. She wonders if Rhett will kiss her, but to her irritation, he does not. He says she looks pale. She says it's because she is pregnant. He sarcastically asks if the father is Ashley. She calls Rhett a cad and tells him no woman would want his baby. He says, "Cheer up, maybe you'll have a miscarriage."[27] She lunges at him, but he dodges, and she tumbles backwards down the stairs. She is seriously ill for the first time in her life, having lost her child and broken her ribs. Rhett is remorseful, believing he has killed her. Sobbing and drunk, he buries his head in Melanie's lap and confesses he had been a jealous cad.

Scarlett, who is thin and pale, goes to Tara, taking Wade and Ella with her, to regain her strength and vitality from "the green cotton fields of home."[28] When she returns healthy to Atlanta, she sells the mills to Ashley. She finds Rhett's attitude has noticeably changed. He is sober, kinder, polite—and seemingly disinterested. Though she misses the old Rhett at times, Scarlett is content to leave well enough alone.

Bonnie is four years old in 1873. Spirited and willful, she has her father wrapped around her finger and giving into her every demand. Even Scarlett is jealous of the attention Bonnie gets. Rhett rides his horse around town with Bonnie in front of him, but Mammy insists it is not fitting for a girl to ride a horse with her dress flying up. Rhett heeds her words and buys Bonnie a Shetland pony, whom she names "Mr. Butler," and teaches her to ride sidesaddle. Then Rhett pays a boy named Wash twenty-five cents to teach Mr. Butler to jump over wood bars. When Mr. Butler is able to get his fat legs over a one-foot bar, Rhett puts Bonnie on the pony, and soon Mr. Butler is leaping bars and Aunt Melly's rose bushes.

Wearing her blue velvet riding habit with a red feather in her black hat, Bonnie pleads with her father to raise the bar to one and a half feet. He gives in, warning her not to come crying if she falls. Bonnie yells to her mother, "Watch me take this one!"[29] The pony gallops towards the wood bar, but trips over it. Bonnie breaks her neck in the fall, and dies.

In the dark days and months following Bonnie's death, Rhett is often drunk and disheveled, while Scarlett, though deeply bereaved also, seems to hold up under the strain. With the untimely death of Melanie Wilkes a short time later, Rhett decides he only wants the calm dignity of the genial South he once knew in his youth and leaves Atlanta to find it. Meanwhile, Scarlett dreams of love that has eluded her for so long. However, she still has Tara and knows she can win Rhett back, because "tomorrow is another day."[30]

Structure

Coming-of-age story

Margaret Mitchell arranged Gone with the Wind chronologically, basing it on the life and experiences of the main character, Scarlett O'Hara, as she grew from adolescence into adulthood. During the time span of the novel, from 1861 to 1873, Scarlett ages from sixteen to twenty-eight years. This is a type of Bildungsroman,[31] a novel concerned with the moral and psychological growth of the protagonist from youth to adulthood (coming-of-age story). Scarlett's development is affected by the events of her time.[31] Mitchell used a smooth linear narrative structure. The novel is known for its exceptional "readability".[32] The plot is rich with vivid characters.

Genre

Gone with the Wind is often placed in the literary subgenre of the historical romance novel.[33] Pamela Regis has argued that is more appropriately classified as a historical novel, as it does not contain all of the elements of the romance genre.[34] The novel has also been described as an early classic of the erotic historical genre, because it is thought to contain some degree of pornography.[35]

Plot discussion

Slavery

'Way back in the dark days of the Early Sixties, regrettable tho it was—men fought, bled, and died for the freedom of the negro—her freedom!—and she stood by and did her duty to the last ditch—

It was and is her life to serve, and she has done it well.

While shot and shell thundered to release the shackles of slavery from her body and her soul—she loved, fought for, and protected—Us who held her in bondage, her "Marster" and her "Missus!"

Excerpt from My Old Black Mammy by James W. Elliott, 1914.[36]

Slavery in Gone with the Wind is a backdrop to a story that is essentially about other things.[37] Southern plantation fiction (also known as Anti-Tom literature, in reference to reactions to Harriet Beecher Stowe's powerful anti-slavery novel, Uncle Tom's Cabin of 1852) from the mid-19th century, culminating in Gone With the Wind, is written from the perspective and values of the slaveholder and tends to present slaves as docile and happy.[38]

Caste system

The characters in the novel are organized into two basic groups along class lines: the white planter class, such as Scarlett and Ashley, and the black house servant class. The slaves depicted in Gone with the Wind are primarily loyal house servants, such as Mammy, Pork, Prissy, and Uncle Peter.[39] House servants are the highest "caste" of slaves in Mitchell's caste system.[40] They choose to stay with their masters after the Emancipation Proclamation of 1863 and subsequent Thirteenth Amendment of 1865 sets them free. Of the servants who stayed at Tara, Scarlett thinks, "There were qualities of loyalty and tirelessness and love in them that no strain could break, no money could buy."[41]

The field slaves make up the lower class in Mitchell's caste system.[40][42] The field slaves from the Tara plantation and the foreman, Big Sam, are taken away by Confederate soldiers to dig ditches[19] and never return to the plantation. Mitchell wrote that other field slaves were "loyal" and "refused to avail themselves of the new freedom",[40] but the novel has no field slaves who stay on the plantation to work after they have been emancipated.

American William Wells Brown escaped from slavery and published his memoir, or slave narrative, in 1847. He wrote of the disparity in conditions between the house servant and the field hand:

During the time that Mr. Cook was overseer, I was a house servant—a situation preferable to a field hand, as I was better fed, better clothed, and not obliged to rise at the ringing bell, but about an half hour after. I have often laid and heard the crack of the whip, and the screams of the slave.[43]

Faithful and devoted slave

Although the novel is more than 1,000 pages long, the character of Mammy never considers what her life might be like away from Tara.[44] She recognizes her freedom to come and go as she pleases, saying, "Ah is free, Miss Scarlett. You kain sen' me nowhar Ah doan wanter go," but Mammy remains duty-bound to "Miss Ellen's chile."[23] (No other name for Mammy is noted in the novel.)

Eighteen years before the publication of Gone with the Wind, an article titled, "The Old Black Mammy," written in the Confederate Veteran in 1918, discussed the romanticized view of the mammy character that had persisted in Southern literature:

...for her faithfulness and devotion, she has been immortalized in the literature of the South; so the memory of her will never pass, but live on in the tales that are told of those "dear dead days beyond recall".[45][46]

Micki McElya, in her book Clinging to Mammy, suggests the myth of the faithful slave, in the figure of Mammy, lingered because white Americans wished to live in a world in which African Americans were not angry over the injustice of slavery.[47]

The best-selling anti-slavery novel from the 19th century is Uncle Tom's Cabin by Harriet Beecher Stowe, published in 1852. Uncle Tom's Cabin is mentioned briefly in Gone with the Wind as being accepted by the Yankees as "revelation second only to the Bible".[41] The enduring interest of both Uncle Tom's Cabin and Gone with the Wind has resulted in lingering stereotypes of 19th-century African-American slaves.[48] Gone with the Wind has become a reference point for subsequent writers about the South, both black and white alike.[49]

Southern belle

| “ | Young misses whut frowns an' pushes out dey chins an' says 'Ah will' an' 'Ah woan' mos' gener'ly doan ketch husbands.[50] | ” |

| — Mammy | ||

The southern belle is an archetype for a young woman of the antebellum American South upper class. The southern belle was believed to be physically attractive but, more importantly, personally charming with sophisticated social skills. She is subject to the correct code of female behavior.[51] The novel's heroine, Scarlett O'Hara, charming though not beautiful, is a classic southern belle.

For young Scarlett, the ideal southern belle is represented by her mother, Ellen O'Hara. In "A Study in Scarlett", published in The New Yorker, Claudia Roth Pierpont wrote:

The Southern belle was bred to conform to a subspecies of the nineteenth-century "lady"... For Scarlett, the ideal is embodied in her adored mother, the saintly Ellen, whose back is never seen to rest against the back of any chair on which she sits, whose broken spirit everywhere is mistaken for righteous calm...[52]

However, Scarlett is not always willing to conform. Kathryn Lee Seidel, in her book, The Southern Belle in the American Novel, wrote:

...part of her does try to rebel against the restraints of a code of behavior that relentlessly attempts to mold her into a form to which she is not naturally suited.[53]

The figure of a pampered southern belle, Scarlett lives through an extreme reversal of fortune and wealth, and survives to rebuild Tara and her self-esteem.[54] Her bad belle traits, Scarlett's deceitfulness, shrewdness, manipulation, and superficiality, in contrast to Melanie's good belle traits, trust, self-sacrifice, and loyalty, enable her to survive in the post-war South, and pursue her main interest, to make enough money to survive and prosper.[55] Although Scarlett was "born" around 1845, she is portrayed to appeal to modern-day readers for her passionate and independent spirit, determination and obstinate refusal to feel defeated.[56]

Some historical background

Marriage was supposed to be the goal of all southern belles, as women's status was largely determined by that of their husbands. All social and educational pursuits were directed towards it. Despite the Civil War and loss of a generation of eligible men, young ladies were still expected to marry.[57] By law and Southern social convention, household heads were adult, white propertied males, and all white women and all African Americans were thought to require protection and guidance because they lacked the capacity for reason and self-control.[58]

The Atlanta Historical Society has produced a number of Gone with the Wind exhibits, among them a 1994 exhibit titled, "Disputed Territories: Gone with the Wind and Southern Myths". The exhibit asked, "Was Scarlett a Lady?", finding that historically most women of the period were not involved in business activities as Scarlett was during Reconstruction, when she ran a sawmill. White women performed traditional jobs such as teaching and sewing, and generally disliked work outside the home.[59]

During the Civil War, Southern women played a major role as volunteer nurses working in makeshift hospitals. Many were middle- and upper class women who had never worked for wages or seen the inside of a hospital. One such nurse was Ada W. Bacot, a young widow who had lost two children. Bacot came from a wealthy South Carolina plantation family that owned 87 slaves.[60]

In the fall of 1862, Confederate laws were changed to permit women to be employed in hospitals as members of the Confederate Medical Department.[61] Twenty-seven-year-old nurse Kate Cumming from Mobile, Alabama, described the primitive hospital conditions in her journal:

They are in the hall, on the gallery, and crowded into very small rooms. The foul air from this mass of human beings at first made me giddy and sick, but I soon got over it. We have to walk, and when we give the men any thing kneel, in blood and water; but we think nothing of it at all.[62]

Battles

The Civil War came to an end on April 26, 1865 when Confederate General Johnston surrendered his armies in the Carolinas Campaign to Union General Sherman. Several battles are mentioned or depicted in Gone with the Wind.

Early and mid war years

- Seven Days Battles, June 25 – July 1, 1862, Richmond, Virginia, Confederate victory.[16]

- Battle of Fredericksburg, December 11 – 15, 1862, Fredericksburg, Virginia, Confederate victory.[63]

- Streight's Raid, April 19 – May 3, 1863, in northern Alabama. Union Colonel Streight and his men were captured by Confederate General Nathan Bedford Forrest.[63]

- Battle of Chancellorsville, April 30 – May 6, 1863, in Spotsylvania County, Virginia, near the village of Chancellorsville, Confederate victory.[63]

- Ashley Wilkes is stationed on the Rapidan River, Virginia, in the winter of 1863,[64] later captured and sent to a Union prison camp, Rock Island.[65]

- Siege of Vicksburg, May 18 – July 4, 1863, Vicksburg, Mississippi, Union victory.[63]

- Battle of Gettysburg, July 1–3, 1863, fought in and around the town of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, Union victory. "They expected death. They did not expect defeat."[63]

- Battle of Chickamauga, September 19–20, 1863, northwestern Georgia. The first fighting in Georgia and the most significant Union defeat.[65]

- Chattanooga Campaign, November–December 1863, Tennessee, Union victory. The city became the supply and logistics base for Sherman's 1864 Atlanta Campaign.[65]

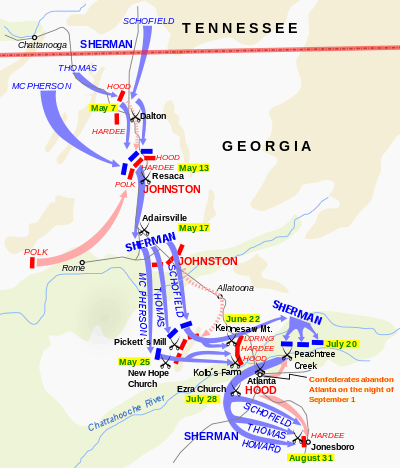

Atlanta Campaign

The Atlanta Campaign (May–September 1864) took place in northwest Georgia and the area around Atlanta.

Confederate General Johnston fights and retreats from Dalton (May 7–13)[19] to Resaca (May 13–15) to Kennesaw Mountain (June 27). Union General Sherman suffers heavy losses to the entrenched Confederate army. Unable to pass through Kennesaw, Sherman swings his men around to the Chattahoochee River where the Confederate army is waiting on the opposite side of the river. Once again, General Sherman flanks the Confederate army, forcing Johnston to retreat to Peachtree Creek (July 20), five miles northeast of Atlanta.

- Battle of Atlanta, July 22, 1864, just southeast of Atlanta. The city would not fall until September 2, 1864. Heavy losses for Confederate General Hood.

- Battle of Ezra Church, July 28, 1864, Sherman's failed attack west of Atlanta where the railroad entered the city.

- Battle of Utoy Creek, August 5–7, 1864, Sherman's failed attempt to break the railroad line at East Point, into Atlanta from the west, heavy Union losses.

- Battle of Jonesborough, August 31 – September 1, 1864, Sherman successfully cut the railroad lines from the south into Atlanta. The city of Atlanta was abandoned by General Hood and then occupied by Union troops for the rest of the war.

March to the Sea

The Savannah Campaign was conducted in Georgia during November and December 1864.

President Lincoln's murder

Although Abraham Lincoln is mentioned in the novel fourteen times, no reference is made to his assassination on April 14, 1865.

Beau ideal

Somebody's darling! so young and so brave!

Wearing still on his pale, sweet face—

Soon to be hid by the dust of the grave—

The lingering light of his boyhood's grace!

Ashley Wilkes is the beau ideal of Southern manhood. A planter by inheritance, Ashley knew the Confederate cause had died at the conclusion of the American Civil War.[67] Ashley's name signifies paleness. His "pallid skin literalizes the idea of Confederate death."[68]

He contemplates leaving Georgia for New York City. Had he gone North, he would have joined numerous other Confederate carpetbaggers there.[67] Ashley, embittered by war, tells Scarlett he has been "in a state of suspended animation" since the surrender.[69] He feels he is not "shouldering a man's burden" at Tara and believes he is "much less than a man—much less, indeed, than a woman".[69]

A "young girl's dream of the Perfect Knight",[70] Ashley is like a young girl himself.[71] With his "poet's eye",[72] Ashley has a "feminine sensitivity".[73] Scarlett is angered by the "slur of effeminacy flung at Ashley" when her father tells her the Wilkes family was "born queer".[74] (Mitchell's use of the word "queer" is for its sexual connotation because queer, in the 1930s, was associated with homosexuality.)[75] Ashley's effeminacy is associated with his appearance, his lack of forcefulness, and sexual impotency.[76] He rides, plays poker, and drinks like "proper men", but his heart is not in it, Gerald claims.[74][77] The embodiment of castration, Ashley wears the head of Medusa on his cravat pin.[74][75]

Scarlett's love interest, Ashley Wilkes, lacks manliness, and her husbands—the "calf-like"[14] Charles Hamilton, and the "old-maid in britches",[14] Frank Kennedy—are unmanly as well. Mitchell is critiquing masculinity in southern society since Reconstruction.[78] Even Rhett Butler, the well-groomed dandy,[79] is effeminate or "gay-coded."[80] Charles, Frank and Ashley represent the impotence of the post-war white South.[68] Its power and influence has been diminished.

Scallawag

The word "scallawag" is defined as a loafer, a vagabond, or a rogue.[81] Scallawag had a special meaning after the Civil War as an epithet for a white Southerner who accepted and supported Republican reforms.[82] Mitchell defines Scallawags as "Southerners who had turned Republican very profitably."[83] Rhett Butler is accused of being a "damned Scallawag."[84] In addition to scallawags, Mitchell portrays other types of scoundrels in the novel: Yankees, carpetbaggers, Republicans, prostitutes, and overseers. In the early years of the Civil War, Rhett is called a "scoundrel" for his "selfish gains" profiteering as a blockade-runner.[85]

As a scallawag, Rhett is despised. He is the "dark, mysterious, and slightly malevolent hero loose in the world".[86] Literary scholars have identified elements of Mitchell's first husband, Berrien "Red" Upshaw, in the character of Rhett.[86] Another sees the image of Italian actor Rudolph Valentino, whom Margaret Mitchell interviewed as a young reporter for The Atlanta Journal.[87][88] Fictional hero Rhett Butler has a "swarthy face, flashing teeth and dark alert eyes".[89] He is a "scamp, blackguard, without scruple or honor."[89]

Dark sexuality

The most passionate and virile character in the novel is Rhett, with whom Margaret Mitchell associates "dark sexuality" and the "black devil."[91] Mitchell's romantic hero is colored—portrayed in blacks and browns. Rhett's symbolic dark image is placed within the context of two other images: the mythic black rapist and the dark-skinned Arab sheik played by screen idol Rudolph Valentino in the film, The Sheik (1921). By portraying Rhett in this manner, Mitchell plays upon racial anxieties and sexual fantasies of the South.[92] Rhett's demons are prostitutes and liquor, as demonstrated by his intimacy with Belle Watling, in whose brothel he often resides,[86] and his bouts of drunkenness. The "black beast rapist" is associated with liquor.[93] Rhett is a "terrifying faceless black bulk" when he appears before Scarlett in a drunken jealous rage on the night of Ashley's party. He shows Scarlett his "large brown hands" and says, "I could tear you to pieces with them."[26][93]

With Rhett's "swarthy face"[89] juxtaposed against Scarlett's "magnolia-white skin,"[13] the two white protagonists are a metaphor for an interracial couple. Their romance crosses racial boundaries in a paradox to the usual white man and black or multi-racial woman, upending racial stereotypes.[94]

Rhett and Scarlett's bedroom scene (Chapter 54) is often read as a rape that was meant to suggest Reconstruction fear of black-on-white rape in the South.[91] Since the late 20th century, critics have suggested the book was built around rape fantasies.[95][96] In one interpretation of the scene, the "dandified dangerous lover" carries Scarlett up the stairs into her first encounter with the erotic.[97] In another interpretation, a marital rape occurs.[98]

Characters

Main characters

- Katie Scarlett (O'Hara) Hamilton Kennedy Butler: is the O'Haras' oldest daughter. Scarlett's forthright Irish blood is always at variance with the French teachings of style from her mother. Scarlett marries Charles Hamilton, Frank Kennedy, and Rhett Butler, all the while wishing she were married instead to Ashley Wilkes. She has three children, one from each husband: Wade Hampton Hamilton (son to Charles Hamilton), Ella Lorena Kennedy (daughter to Frank Kennedy), and Eugenie Victoria "Bonnie Blue" Butler (daughter to Rhett Butler). She miscarries a fourth child, the only one she wanted, during a quarrel with Rhett when she accidentally falls down the stairs.[27] Scarlett is secretly scornful of Melanie Wilkes,[8] wife to Ashley. The other woman shows nothing but love and devotion toward Scarlett, and considers her a sister throughout her life because Scarlett married Melanie's brother Charles.[15] Scarlett is unaware of the extent of Rhett's love for her or that she might love him.[89]

- Captain Rhett K. Butler: is Scarlett's admirer and her third husband. He is often publicly shunned for his scandalous behavior[14] and sometimes accepted for his charm. Rhett declares he is not a marrying man and propositions Scarlett to be his mistress,[99] but marries her after the death of Frank Kennedy. He says he won't risk losing her to someone else, since it is unlikely she will ever need money again.[23] At the end of the novel, Rhett confesses to Scarlett, "I loved you but I couldn't let you know it. You're so brutal to those who love you, Scarlett."[30]

- Major George Ashley Wilkes: The gallant Ashley married his cousin, Melanie, because, "Like must marry like or there'll be no happiness."[14] A man of honor, Ashley enlisted in the Confederate States Army though he says he would have freed his slaves after his father's death, if the war hadn't done it first.[28] Although many of his friends and relations were killed in the Civil War, Ashley survived to see its brutal aftermath. Ashley was "the Perfect Knight",[70] in the mind of Scarlett, even throughout her three marriages. "She loved him and wanted him and did not understand him."[74]

- Melanie (Hamilton) Wilkes: is Ashley's wife and cousin. Melanie is a humble, serene and gracious Southern woman.[69] As the story unfolds, Melanie becomes progressively physically weaker, first by childbirth, then "the hard work she had done at Tara,"[69] and she dies after a miscarriage.[100] As Rhett Butler said, "She never had any strength. She's never had anything but heart."[100]

Minor characters

| “ | I made Tara up, just as I made up every character in the book. But nobody will believe me.[101] | ” |

| — Margaret Mitchell | ||

Scarlett's immediate family

- Ellen (Robillard) O'Hara: is Scarlett's mother of French ancestry. Ellen married Gerald O'Hara, who was 28 years her senior, after her true love, Philippe Robillard, was killed in a bar fight. She is Scarlett's ideal of a "great lady".[50] Ellen ran all aspects of the household and nursed negro slaves as well as poor white trash.[50] She dies from typhoid fever in August 1864 after nursing Emmie Slattery.[8]

- Gerald O'Hara: is Scarlett's florid Irish father.[13] An excellent horseman,[74] Gerald likes to jump fences on horseback while intoxicated, which eventually leads to his death.[102] Gerald's mind becomes addled after the death of his wife, Ellen.[103]

- Susan Elinor ("Suellen") O'Hara: is Scarlett's middle sister. She became sickened by typhoid during the siege of Atlanta.[99] After the war, Scarlett steals and marries her beau, Frank Kennedy.[21] Later, Suellen marries Will Benteen and has at least one child, Susie, with him.[69]

- Caroline Irene ("Carreen") O'Hara: is Scarlett's youngest sister, who also was ill with typhoid during the siege of Atlanta.[99] She is infatuated with and later engaged to the red-headed Brent Tarleton, who is killed in the war.[104] Broken-hearted by Brent's death, Carreen never truly gets over it. Years later she joins a convent.[102]

- O'Hara Boys: are the three boys of Ellen and Gerald O'Hara who died in infancy and are buried 100 yards from the house. Each was named Gerald after the father; they died in succession. The headstone of each boy is inscribed "Gerald O'Hara, Jr."[50] (It was typical of families to name the next living child after the parental namesake, even if a child had already died of that name.)

- Charles Hamilton: is Melanie Wilkes' brother and Scarlett's first husband. Charles is a shy and loving boy.[14] Father to Wade Hampton, Charles died before reaching a battlefield or seeing his son.[15]

- Wade Hampton Hamilton: is the son of Scarlett and Charles, born in early 1862. He was named for his father's commanding officer, Wade Hampton III, later governor of South Carolina.[15]

- Frank Kennedy: is Suellen O'Hara's former fiancé and Scarlett's second husband. Frank is an unattractive older man. He originally proposes to Suellen but Scarlett steals him in order to have enough money to pay the taxes on Tara and keep it.[105] Frank is unable to comprehend Scarlett's fears and her desperate struggle for survival after the war. He is unwilling to be as ruthless in business as Scarlett would like.[105] Unknown to Scarlett, Frank is secretly involved in the Ku Klux Klan. He is "shot through the head",[106] according to Rhett Butler, while attempting to defend Scarlett's honor after she is attacked.

- Ella Lorena Kennedy: is the homely daughter of Scarlett and Frank.[22]

- Eugenie Victoria "Bonnie Blue" Butler: is Scarlett and Rhett's pretty, strong-willed daughter. She is as Irish in looks and temper as Gerald O'Hara, with the same blue eyes.[24]

Tara

- Mammy: is Scarlett's nurse from birth. A slave, she originally was held by Scarlett's grandmother and raised her mother, Ellen O'Hara.[74] Mammy is "head woman of the plantation."[107]

- Pork: is Gerald O'Hara's valet and his first slave. He won Pork in a game of poker (as he did the plantation Tara, in a separate poker game).[50] When Gerald died, Scarlett gave his pocket watch to Pork. She wanted to have the watch engraved with the words, "To Pork from the O'Haras—Well done good and faithful servant,"[69] but Pork declined the offer.

- Dilcey: is Pork's wife and a slave woman of mixed Indian and African descent.[108] Scarlett pushes her father into buying Dilcey and her daughter Prissy from John Wilkes, the latter as a favor to Dilcey that she never forgets.[74]

- Prissy: is a slave girl, Dilcey's daughter.[108] Prissy is Wade's nurse and goes with Scarlett to Atlanta when she lives with Aunt Pittypat.[15]

- Jonas Wilkerson: is the Yankee overseer of Tara before the Civil War.[108]

- Big Sam: is a strong, hardworking field slave and the foreman at Tara. In post-war lawlessness, Big Sam comes to Scarlett's rescue from would-be thieves.[109]

- Will Benteen: is a "South Georgia cracker,"[104] Confederate soldier, and patient listener to the troubles of all. Will lost part of his leg in the war and walks with the aid of a wooden stump. He is taken in by the O'Haras on his journey home from the war; after his recovery he stays on to manage the farm at Tara.[104] Fond of Carreen O'Hara, he is disappointed when she decides to enter a convent.[102] Not wanting to leave Tara, he later marries Suellen and has at least one child, Susie, with her.[69]

Clayton County

- India Wilkes: is the sister of Honey and Ashley Wilkes. She is described as plain. India was courted by Stuart Tarleton before he and his brother Brent both fell in love with Scarlett.[13]

- Honey Wilkes: is the sister of India and Ashley Wilkes. Honey is described as having the "odd lashless look of a rabbit."[14]

- John Wilkes: is owner of "Twelve Oaks"[74] and patriarch of the Wilkes family. John Wilkes is educated and gracious.[14] He is killed during the siege of Atlanta.[99]

- Tarleton Boys: Boyd, Tom, and the twins, Brent and Stuart: The red-headed Tarleton boys were in frequent scrapes, loved practical jokes and gossip, and "were worse than the plagues of Egypt,"[13] according to their mother. The inseparable twins, Brent and Stuart, at 19 years old were six feet two inches tall.[13] All four boys were killed in the war, the twins just moments apart at the Battle of Gettysburg.[110] Boyd was buried somewhere in Virginia.[63]

- Tarleton Girls: Hetty, Camilla, 'Randa and Betsy: The stunning Tarleton girls have varying shades of red hair.[107]

- Beatrice Tarleton: is the mistress of the "Fairhill" plantation.[107] She was a busy woman, managing a large cotton plantation, a hundred negroes, and eight children, and the largest horse-breeding farm in Georgia. Hot-tempered, she believed that "a lick every now and then did her boys no harm."[13]

- Calvert Family: Raiford, Cade and Cathleen: are the O'Haras' Clayton County neighbors from another plantation, "Pine Bloom".[110] Cathleen Calvert was young Scarlett's friend.[107] Their widowed father Hugh married a Yankee governess, who was called "the second Mrs. Calvert."[111] Next to Scarlett, Cathleen "had had more beaux than any girl in the County,"[110] but eventually married their former Yankee overseer, Mr. Hilton.

- Fontaine Family: Joe, Tony and Alex are known for their hot tempers. Joe is killed at Gettysburg,[63] while Tony murders Jonas Wilkerson in a barroom and flees to Texas, leaving Alex to tend to their plantation.[40] Grandma Fontaine, also known as "Old Miss," is the wife of old Doc Fontaine, the boys' grandfather. "Young Miss" and young Dr. Fontaine, the boys' parents, and Sally (Munroe) Fontaine, wife to Joe,[112] make up the remaining family of the "Mimosa" plantation.[111]

- Emmie Slattery: is poor white trash. The daughter of Tom Slattery, her family lived on three acres along the swamp bottoms between the O'Hara and Wilkes plantations.[50] Emmie gave birth to an illegitimate child fathered by Jonas Wilkerson, a Yankee and the overseer at Tara.[108] The child died. Emmie later married Jonas. After the war, flush with carpetbagger cash, they try to buy Tara, but Scarlett refuses the offer.[113]

Atlanta

- Aunt Pittypat Hamilton: Named Sarah Jane Hamilton, she acquired the nickname "Pittypat" in childhood because of the way she walked on her tiny feet. Aunt Pittypat is a spinster who lives in the red-brick house at the quiet end of Peachtree Street in Atlanta. The house is half-owned by Scarlett (after the death of Charles Hamilton). Pittypat's financial affairs are managed by her brother, Henry, whom she doesn't especially care for. Aunt Pittypat raised Melanie and Charles Hamilton after the death of their father, with considerable help from her slave, Uncle Peter.[114]

- Uncle Henry Hamilton: is Aunt Pittypat's brother, an attorney, and the uncle of Charles and Melanie.[114]

- Uncle Peter: is an older slave, who serves as Aunt Pittypat's coach driver and general factotum. Uncle Peter looked after Melanie and Charles Hamilton when they were young.[114]

- Beau Wilkes: is Melanie and Ashley's son, who is born in Atlanta when the siege begins and transported to Tara after birth.[115]

- Archie: is an ex-convict and former Confederate soldier who was imprisoned for the murder of his adulterous wife before the war. Archie is taken in by Melanie and later becomes Scarlett's coach driver.[22]

- Meade Family: Atlanta society considers Dr. Meade to be "the root of all strength and all wisdom."[114] He looks after injured soldiers during the siege with assistance from Melanie and Scarlett.[116] Mrs. Meade is on the bandage-rolling committee.[114] Their two sons are killed in the war.[116]

- Merriwether Family: Mrs. Dolly Merriwether is an Atlanta dowager along with Mrs. Elsing and Mrs. Whiting.[114] Post-war she sells homemade pies to survive, eventually opening her own bakery.[69] Her father-in-law Grandpa Merriwether fights in the Home Guard[117] and survives the war. Her daughter Maybelle marries René Picard, a Louisiana Zouave.[16]

- Belle Watling: is a prostitute[85] and brothel madam[40] who is portrayed as a loyal Confederate.[85] Melanie declares she will acknowledge Belle when she passes her in the street, but Belle tells her not to.[106]

Robillard family

- Pierre Robillard: is the father of Ellen O'Hara. He was staunchly Presbyterian even though his family was Roman Catholic. The thought of his daughter becoming a nun was worse than her marrying Gerald O'Hara.[50]

- Solange Robillard: is the mother of Ellen O'Hara and Scarlett's grandmother. She was a dainty Frenchwoman who was snooty and cold.[74]

- Eulalie and Pauline Robillard: are the married sisters of Ellen O'Hara who live in Charleston.[15]

- Philippe Robillard: is the cousin of Ellen O'Hara and her first love. Philippe died in a bar fight in New Orleans around 1844.[74]

Themes

Survival

If Gone with the Wind has a theme it is that of survival. What makes some people come through catastrophes and others, apparently just as able, strong, and brave, go under? It happens in every upheaval. Some people survive; others don't. What qualities are in those who fight their way through triumphantly that are lacking in those that go under? I only know that survivors used to call that quality 'gumption.' So I wrote about people who had gumption and people who didn't.[1]

— Margaret Mitchell,1936

Color symbolism

Mitchell's use of color in the novel is symbolic and open to interpretation. Red, green, and a variety of hues of each of these colors, are the predominant palette of colors related to Scarlett.[118] She is also linked to white by the color of her skin. Symbolically, red and green have been broadly defined to mean "vitality" (red) and "rebirth" (green).[118] Mitchell interwove the two colors into her description of the Tara plantation: "red fields with springing green cotton".[15] The red fields are "blood-colored after rains".[13] The whitewashed brick plantation house is virtually nondescript by comparison to the plantation fields and sits like an island in a sea of red.[13] In springtime, the lawn around the plantation house turns emerald green.[50]

For the Irish and others, green in the novel represents Mitchell's commemoration of her "Green Irish heritage." Gerald O'Hara pridefully sings "The Wearin 'o the Green".[107][119] Scarlett's green-coded Irish identity is the strength that ensures she will thrive post-war.[120] Rhett likens Scarlett's strength to the mythological figure Antaeus, who stays strong only when he is in contact with his Mother Earth.[28] Scarlett's mythical mother is Tara.[121]

Scarlett is not all green; her name suggests the "erotically-charged color" red. The only openly "scarlet woman" in the novel is the red-headed Belle Watling,[122] whose hair is "too red to be true".[114] Mammy is reluctant to reveal her red petticoat to Rhett;[24] nevertheless, she has sexual knowledge akin to Belle Watling.[123] Scarlett, whom Mitchell pits against the war, "prostitutes" herself to pay the taxes on Tara. By her name, Scarlett evokes emotions and images of the color scarlet: "blood, passion, anger, sexuality, madness".[124]

Reception

Reviews

The sales of Margaret Mitchell's novel in the summer of 1936, deep in the Great Depression and at the virtually unprecedented high price of three dollars, reached about one million by the end of December.[32] The book was a bestseller by the time reviews began to appear in national magazines.[5] Herschel Brickell, a critic for the New York Evening Post, lauded Mitchell for the way she "tosses out the window all the thousands of technical tricks our novelists have been playing with for the past twenty years."[125]

Ralph Thompson, a book reviewer for The New York Times, was critical of the length of the novel, and wrote in June 1936:

I happen to feel that the book would have been infinitely better had it been edited down to say, 500 pages, but there speaks the harassed daily reviewer as well as the would-be judicious critic. Very nearly every reader will agree, no doubt, that a more disciplined and less prodigal piece of work would have more nearly done justice to the subject-matter.[126]

Racial, ethnicity and social issues

Gone with the Wind has been criticized for its stereotypical and derogatory portrayal of African Americans in the 19th century South.[128] Former field hands during the early days of Reconstruction are described behaving "as creatures of small intelligence might naturally be expected to do. Like monkeys or small children turned loose among treasured objects whose value is beyond their comprehension, they ran wild—either from perverse pleasure in destruction or simply because of their ignorance."[40]

Commenting on this passage of the novel, Jabari Asim, author of The N Word: Who Can Say It, Who Shouldn't, and Why, says it is, "one of the more charitable passages in Gone With the Wind, Margaret Mitchell hesitated to blame black 'insolence'[40] during Reconstruction solely on 'mean niggers',[40] of which, she said, there were few even in slavery days."[129]

Critics say that Mitchell downplayed the violent role of the Ku Klux Klan and their abuse of freedmen. Author Pat Conroy, in his preface to a later edition of the novel, describes Mitchell's portrayal of the Ku Klux Klan as having "the same romanticized role it had in The Birth of a Nation and appears to be a benign combination of the Elks Club and a men's equestrian society".[130]

Regarding the historical inaccuracies of the novel, historian Richard N. Current points out:

No doubt it is indeed unfortunate that Gone with the Wind perpetuates many myths about Reconstruction, particularly with respect to blacks. Margaret Mitchell did not originate them and a young novelist can scarcely be faulted for not knowing what the majority of mature, professional historians did not know until many years later.[131]

In Gone with the Wind, Mitchell is blind to racial oppression and "the inseparability of race and gender" that defines the southern belle character of Scarlett, according to literary scholar Patricia Yaeger.[132] Still, Mitchell explores some complexities in racial issues. Scarlett was asked by a Yankee woman for advice on who to appoint as a nurse for her children; Scarlett suggested a "darky", much to the disgust of the Yankee woman who was seeking an Irish maid, a "Bridget".[41] African Americans and Irish Americans are treated "in precisely the same way" in Gone with the Wind, writes David O'Connell in his 1996 book, The Irish Roots of Margaret Mitchell's Gone With the Wind. Ethnic slurs on the Irish and Irish stereotypes pervade the novel, O'Connell claims, and Scarlett is not an exception to the insults.[133] Irish scholar Geraldine Higgins notes that Jonas Wilkerson labels Scarlett: "you highflying, bogtrotting Irish".[134] Higgins says that, as the Irish American O'Haras were slaveholders and African Americans were held in bondage, the two ethnic groups are not equivalent in the ethnic hierarchy of the novel.[135]

The novel has been criticized for promoting plantation values. Mitchell biographer Marianne Walker, author of Margaret Mitchell and John Marsh: The Love Story Behind Gone with the Wind, believes that those who attack the book on these grounds have not read it. She said that the popular 1939 film "promotes a false notion of the Old South". Mitchell was not involved in the screeplay or film production.[136]

James Loewen, author of Lies My Teacher Told Me: Everything Your American History Textbook Got Wrong, says this novel should be taught in schools. Students should be told that Gone with the Wind presents the "wrong" view of slavery, Loewen states.[128] In 1984, an alderman in Waukegan, Illinois, challenged the book's inclusion on the reading list of the Waukegan School District on the grounds of "racism" and "unacceptable language." He objected to the frequent use of the racial slur nigger. He also objected to several other books: The Nigger of the 'Narcissus', Uncle Tom's Cabin, and Adventures of Huckleberry Finn for the same reason.[137]

Awards and recognition

In 1937, Margaret Mitchell received the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction for Gone with the Wind and the second annual National Book Award from the American Booksellers Association.[138] It is ranked as the second favorite book by American readers, just behind the Bible, according to a 2008 Harris Poll.[139] The poll found the novel has its strongest following among women, those aged 44 or more, both Southerners and Midwesterners, both whites and Hispanics, and those who have not attended college. In a 2014 Harris poll, Mitchell's novel ranked again as second, after the Bible.[140] The novel is on the list of best-selling books. As of 2010, more than 30 million copies have been printed in the United States and abroad.[141] More than 24 editions of Gone with the Wind have been issued in China.[141] TIME magazine critics, Lev Grossman and Richard Lacayo, included the novel on their list of the 100 best English-language novels from 1923 to the present (2005).[142][143] In 2003 the book was listed at number 21 on the BBC's The Big Read poll of the UK's "best-loved novel."[144]

Adaptations

Gone with the Wind has been adapted several times for stage and screen:

- The novel is the basis of the Academy Award-winning 1939 film produced by David Oliver Selznick and starring Clark Gable and Vivien Leigh.[145]

- The book was adapted into a musical, Scarlett, which opened in Tokyo in 1970 (in 1966 it was produced as a nine-hour play without music), and in London in 1972, where it was reduced to four hours. The London production opened in 1973 in Los Angeles, and again in Dallas in 1976.[146]

- The Japanese Takarazuka Revue produced a musical adaptation of the novel, Kaze to Tomo ni Sarinu, which was performed by the all female Moon Troupe in 1977.[147] The most recent performance was in January 2014 by the Moon Troupe, with Todoroki Yuu as Rhett Butler and Ryu Masaki as Scarlett O'Hara.[148]

- A 2003 French musical adaptation was produced by Gérard Presgurvic, Autant en Emporte le Vent.[149]

- The book was adapted into a British musical, Gone with the Wind, and opened in 2008 in the U.K. at the New London Theatre.[150]

- A full-length three-act classical ballet version, with a score arranged from the works of Antonín Dvořák and choreographed by Lilla Pártay, premiered in 2007 as performed by the Hungarian National Ballet. It was revived in their 2013 season.[151]

- A new stage adaptation by Niki Landau premiered at the Manitoba Theatre Center in Winnipeg, Canada, in January 2013.[152]

In popular culture

Gone with the Wind has appeared in many places and forms in popular culture:

Books, television and more

- A 1945 cartoon by World War II cartoonist, Bill Mauldin, shows an American soldier lying on the ground with Margaret Mitchell's bullet-riddled book. The caption reads: "Dear, Dear Miss Mitchell, You will probably think this is an awful funny letter to get from a soldier, but I was carrying your big book, Gone with the Wind, under my shirt and a ..."[153]

- In the season 3 episode of I Love Lucy, "Lucy Writes a Novel", which aired on April 5, 1954, "Lucy" (Lucille Ball) reads about a housewife who makes a fortune writing a novel in her spare time. Lucy writes her own novel, which she titles Real Gone with the Wind.[154]

- Gone with the Wind is the book that S. E. Hinton's runaway teenage characters, "Ponyboy" and "Johnny," read while hiding from the law in the young adult novel The Outsiders (1967).[155]

- A film parody titled "Went with the Wind!" aired in a 1976 episode of The Carol Burnett Show.[156] Burnett, as "Starlett", descends a long staircase wearing a green curtain complete with hanging rod. The outfit, designed by Bob Mackie, is displayed at the Smithsonian Institution.[157]

- MAD magazine created a parody of the novel, "Groan With the Wind" (1991),[158] in which Ashley was renamed "Ashtray" and Rhett became "Rhetch." It ends with Rhetch and Ashtray running off together.[71]

- A pictorial parody in which the slaves are white and the protagonists are black appeared in a 1995 issue of Vanity Fair titled, "Scarlett 'n the Hood".[159]

- In a MADtv comedy sketch (2007),[160] "Slave Girl #8" introduces three alternative endings to the film. In one ending, Scarlett pursues Rhett wearing a jet pack.[161]

- In the book Maximum Ride: School's Out Forever (2006), the character of eleven-year-old "Nudge" references Gone with the Wind, and specifically Tara, when she asks her guardian Anne about her house.

Collectibles

A wide array of collectibles related to both the novel and film are available for purchase, especially on auction websites. Items include vintage lamps, figurines, matchbooks, cookbooks, collector plates and various editions of the novel.

On June 30, 1986, the 50th anniversary of the day Gone with the Wind went on sale, the U.S. Post Office issued a 1-cent stamp showing an image of Margaret Mitchell. The stamp was designed by Ronald Adair and was part of the U.S. Postal Service's Great Americans series.[162]

On September 10, 1998, the U.S. Post Office issued a 32-cents stamp as part of its Celebrate the Century series recalling various important events in the 20th century. The stamp, designed by Howard Paine, displays the book with its original dust jacket, a white Magnolia blossom, and a hilt placed against a background of green velvet.[162]

To commemorate the 75th anniversary (2011) of the publication of Gone with the Wind in 1936, Scribner published a paperback edition featuring the book's original jacket art.[163]

The Windies

The Windies are ardent Gone with the Wind fans who follow all the latest news and events surrounding the book and film. They gather periodically in costumes from the film or dressed as Margaret Mitchell. Atlanta, Georgia is their mecca.[164]

Legacy

One enduring legacy of Gone with the Wind is that people worldwide incorrectly think it was the "true story" of the Old South and how it was changed by the American Civil War and Reconstruction. The film adaptation of the novel "amplified this effect."[165] The plantation legend was "burned" into the mind of the public through Mitchell's vivid prose.[166] Moreover, her fictional account of the war and its aftermath has influenced how the world has viewed the city of Atlanta for successive generations.[167]

Some readers of the novel have seen the film first and read the novel afterward. One difference between the film and the novel is the staircase scene, in which Rhett carries Scarlett up the stairs. In the film, Scarlett weakly struggles and does not scream as Rhett starts up the stairs. In the novel, "he hurt her and she cried out, muffled, frightened."[26][98]

Earlier in the novel, in an intended rape at Shantytown (Chapter 44), Scarlett is attacked by a black man who rips open her dress while a white man grabs hold of the horse's bridle. She is rescued by another black man, Big Sam.[91] In the film, she is attacked by a white man, while a black man grabs the horse's bridle.

The Library of Congress began a multiyear "Celebration of the Book" in July 2012 with an exhibition on Books That Shaped America, and an initial list of 88 books by American authors that have influenced American lives. Gone with the Wind was included in the Library's list. Librarian of Congress, James H. Billington said:

This list is a starting point. It is not a register of the 'best' American books – although many of them fit that description. Rather, the list is intended to spark a national conversation on books written by Americans that have influenced our lives, whether they appear on this initial list or not.[168]

Among books on the list considered to be the Great American Novel were Moby-Dick, Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, The Great Gatsby, The Grapes of Wrath, The Catcher in the Rye, Invisible Man, and To Kill a Mockingbird.

Throughout the world, the novel appeals due to its universal themes: war, love, death, racial conflict, class, gender and generation, which speak especially to women.[169] In the police state of North Korea, readers relate to the novel's theme of survival, finding it to be "the most compelling message of the novel".[170] The China Post claimed that Mitchell's first choice of a title for the book was "Tote Your Heavy Bag."[171] Margaret Mitchell's personal collection of nearly 70 foreign language translations of her novel was given to the Atlanta Public Library after her death.[172]

On August 16, 2012, the Archdiocese of Atlanta announced that it had been bequeathed a 50% stake in the trademarks and literary rights to Gone With the Wind from the estate of Margaret Mitchell's deceased nephew, Joseph Mitchell. One of Mitchell's biographers, Darden Asbury Pyron, stated that Margaret Mitchell had "an intense relationship" with her mother, who was a Roman Catholic.

Margaret Mitchell had separated from the Catholic Church.[173]

Original manuscript

Although some of Mitchell's papers and documents related to the writing of Gone with the Wind were burned after her death, many documents, including assorted draft chapters, were preserved.[174] The last four chapters of the novel are held by the Pequot Library of Southport, Connecticut.[175]

Publication and reprintings (1936-USA)

The first printing of 10,000 copies contains the original publication date: "Published May, 1936". After the book was chosen as the Book-of-the-Month's selection for July, publication was delayed until June 30. The second printing of 25,000 copies (and subsequent printings) contains the release date: "Published June, 1936." The third printing of 15,000 copies was made in June 1936. Additionally, 50,000 indistinguishable copies were printed for the Book-of-the-Month Club July selection. Gone with the Wind was officially released to the American public on June 30, 1936.[176] A summary table of printings for 1936 is shown below:

| Year | Month | Number of Times Printed[177] |

|---|---|---|

| 1936 | June | published and reprinted twice |

| 1936 | July | 3 |

| 1936 | August | 6 |

| 1936 | September | 4 |

| 1936 | October | 6 (7)[178] |

| 1936 | November | 3 (4)[178] |

| 1936 | December | 2 |

Sequels and prequels

Although Mitchell refused to write a sequel to Gone with the Wind, Mitchell's estate authorized Alexandra Ripley to write a sequel, which was titled Scarlett.[179] The book was subsequently adapted into a television mini-series in 1994.[180] A second sequel was authorized by Mitchell's estate titled Rhett Butler's People, by Donald McCaig.[181] The novel parallels Gone With the Wind from Rhett Butler's perspective. In 2010, Mitchell's estate authorized McCaig to write a prequel, which follows the life of the house servant Mammy, whom McCaig names "Ruth". The novel, Ruth's Journey, was released in 2014.[182]

The copyright holders of Gone with the Wind attempted to suppress publication of The Wind Done Gone by Alice Randall,[183] which retold the story from the perspective of the slaves. A federal appeals court denied the plaintiffs an injunction (Suntrust v. Houghton Mifflin) against publication on the basis that the book was parody and therefore protected by the First Amendment. The parties subsequently settled out of court and the book went on to become a New York Times Best Seller.

A book sequel unauthorized by the copyright holders, The Winds of Tara by Katherine Pinotti,[184] was blocked from publication in the United States. The novel was republished in Australia, avoiding U.S. copyright restrictions.

Numerous unauthorized sequels to Gone with the Wind have been published in Russia, mostly under the pseudonym Yuliya Hilpatrik, a cover for a consortium of writers. The New York Times states that most of these have a "Slavic" flavor.[185]

Several sequels were written in Hungarian under the pseudonym Audrey D. Milland or Audrey Dee Milland, by at least four different authors (who are named in the colophon as translators to make the book seem a translation from the English original, a procedure common in the 1990s but prohibited by law since then). The first one picks up where Ripley's Scarlett ended, the next one is about Scarlett's daughter Cat. Other books include a prequel trilogy about Scarlett's grandmother Solange and a three-part miniseries of a supposed illegitimate daughter of Carreen.[186]

See also

- Lost Laysen, a 1916 novella written by Mitchell

- Southern literature

- Southern Renaissance

- Le Monde's 100 Books of the Century

References

- ↑ Obituary: Miss Mitchell, 49, Dead of Injuries (August 17, 1949) New York Times. Retrieved May 14, 2011.

- 1 2 "People on the Home Front: Margaret Mitchell", Sgt. H. N. Oliphant, Yank, (October 19, 1945), p. 9. Retrieved May 12, 2011.

- 1 2 Gavin Lambert, "The Making of Gone With the Wind", Atlantic Monthly, (February 1973). Retrieved May 14, 2011.

- 1 2 Joseph M. Flora, Lucinda H. MacKethan, Todd Taylor (2002), The Companion to Southern Literature: themes, genres, places, people, movements and motifs, Louisiana State University Press, p. 308. ISBN 0-8071-2692-6

- ↑ Jenny Bond and Chris Sheedy (2008), Who the Hell is Pansy O'Hara?: The Fascinating Stories Behind 50 of the World's Best-Loved Books, Penguin Books, p. 96. ISBN 978-0-14-311364-5

- ↑ Ernest Dowson (1867–1900), "Non Sum Qualis Eram Bonae sub Regno Cynarae". Retrieved March 31, 2012

- 1 2 3 Part 3, Chapter 24

- ↑ John Hollander, (1981) The Figure of Echo: a mode of allusion in Milton and after, University of California Press, p. 107. ISBN 978-0-520-05323-6

- ↑ William Flesch, (2010) The Facts on File Companion to British Poetry, 19th century, Infobase Publishing, p. 89. ISBN 978-0-8160-5896-9

- ↑ Poem of the week: "Non sum qualis eram bonae sub regno Cynarae" by Ernest Dowson, Carol Rumen (March 14, 2011) The Guardian. Retrieved January 2, 2014.

- ↑ Ellen F. Brown and John Wiley (2011), Margaret Mitchell's Gone With the Wind: A Bestseller's Odyssey from Atlanta to Hollywood, Taylor Trade Publishing, p. 59 & 60. ISBN 978-1-58979-567-9

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Part 1, chapter 1

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Part 1, chapter 6

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Part 1, chapter 7

- 1 2 3 4 5 Part 2, chapter 9

- ↑ "When this Cruel War is Over (Weeping, Sad and Lonely)", Charles C. Sawyer and Henry Tucker, published by J. C. Schreiner & Son, Savannah, Georgia, 1862. Stephen Collins Foster: Popular American Music Collection.

- ↑ Weeping Sad and Lonely sung by Elizabeth Foster from the documentary Civil War Songs and Stories, copyright Nashville Public Television, 2011

- 1 2 3 4 Part 3, chapter 17

- ↑ Part 3, chapter 22

- 1 2 Part 4, chapter 35

- 1 2 3 Part 4, chapter 42

- 1 2 3 4 Part 4, chapter 47

- 1 2 3 4 Part 5, chapter 50

- ↑ Part 5, chapter 53

- 1 2 3 4 Part 5, chapter 54

- 1 2 Part 5, chapter 56

- 1 2 3 Part 5, chapter 57

- ↑ Part 5, chapter 59

- 1 2 Part 5, chapter 63

- 1 2 Kathryn Lee Seidel (1985), The Southern Belle in the American Novel, University Presses of Florida, p. 53. ISBN 0-8130-0811-5

- 1 2 "A Critic at Large: A Study in Scarlett" Claudia Roth Pierpont, (August 31, 1992) The New Yorker, p. 87. Retrieved May 15, 2011.

- ↑ Ken Gelder (2004), Popular Fiction: the logics and practices of a literary field, New York: Taylor & Francis e-Library, p. 49. ISBN 0-203-02336-6

- ↑ Pamela Regis (2011), A Natural History of the Romance Novel, University of Pennsylvania Press, p. 48. ISBN 0-8122-1522-2

- ↑ Deborah Lutz (2006), The Dangerous Lover: Villains, Byronism, and the nineteenth-century seduction narrative, The Ohio State University, p. 1 & 7. ISBN 978-0-8142-1034-5

- ↑ James W. Elliott (1914), My Old Black Mammy, New York City: Published weekly by James W. Elliott, Inc. OCLC 823454

- ↑ Junius P. Rodriguez (2007), Slavery in the United States: a social, political and historical encyclopedia. Santa Barbara: ABC-CLIO, Vol. 2: p. 372. ISBN 978-1-85109-549-0

- ↑ Tim A. Ryan (2008), Calls and Responses: the American Novel of Slavery since Gone With the Wind, Louisiana State University Press, p. 69. ISBN 978-0-8071-3322-4.

- ↑ Ryan (2008), Calls and Responses, p. 22-23.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Part 4, chapter 37

- 1 2 3 Part 4, chapter 38

- ↑ Ryan (2008), Calls and Responses, p. 23.

- ↑ William Wells Brown (1847), Narrative of William W. Brown, Fugitive Slave, Boston: Published at the Anti-Slavery Office, No. 25 Cornhill, p. 15. OCLC 12705739

- ↑ Kimberly Wallace-Sanders (2008), Mammy: a century of race and Southern memory, University of Michigan Press, p. 130. ISBN 978-0-472-11614-0

- ↑ "The Old Black Mammy", (January 1918) Confederate Veteran. Retrieved April 24, 2011.

- ↑ "Love's Old, Sweet Song", J.L. Molloy and G. Clifton Bingham, 1884. Retrieved April 27, 2011.

- ↑ Micki McElya (2007), Clinging to Mammy: the faithful slave in twentieth-century America, Harvard University Press, p. 3. ISBN 978-0-674-02433-5

- ↑ Flora, J.M., et al., The Companion to Southern Literature: themes, genres, places, people, movements and motifs, pp. 140–144.

- ↑ Carolyn Perry and Mary Louise Weaks (2002), The History of Southern Women's Literature, Louisiana State University Press, p. 261. ISBN 0-8071-2753-1

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Part 1, chapter 3

- ↑ Seidel, K.L., The Southern Belle in the American Novel, p. 53-54

- ↑ Pierpont, C.R.," A Critic at Large: A Study in Scarlett", p. 92.

- ↑ Seidel, K.L., The Southern Belle in the American Novel, p. 54.

- ↑ Perry, C., et al., The History of Southern Women's Literature, pp. 259, 261.

- ↑ Betina Entzminger (2002), The Belle Gone Bad: White Southern women writers and the dark seductress, Louisiana State University Press, p. 106. ISBN 0-8071-2785-X

- ↑ Why we love -- and hate -- 'Gone with the Wind'. Todd Leopold (December 31, 2014) CNN. Retrieved February 26, 2015.

- ↑ Giselle Roberts (2003), The Confederate Belle, University of Missouri Press, p.87-88. ISBN 0-8262-1464-9

- ↑ Laura F. Edwards (2000), Scarlett Doesn't Live Here Anymore: Southern Women and the Civil War Era, University of Illinois Press, p. 3. ISBN 0-252-02568-7

- ↑ Jennifer W. Dickey (2014), A Tough Little Patch of History: Gone with the Wind and the politics of memory, University of Arkansas Press, p. 66. ISBN 978-1-55728-657-4

- ↑ Ada W. Bacot and Jean V. Berlin (1994), A Confederate Nurse: The Diary of Ada W. Bacot, 1860–1863, University of South Carolina Press, pp. ix–x, 1, 4. ISBN 1-57003-386-2

- ↑ Kate Cumming and Richard Barksdale Harwell (1959), Kate: The Journal of a Confederate Nurse, Louisiana State University Press, p. xiii. ISBN 978-0-8071-2267-9

- ↑ Cumming, K., et al., Kate: The Journal of a Confederate Nurse, p. 15.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Part 2, chapter 14

- ↑ Part 2, chapter 15

- 1 2 3 Part 2, chapter 16

- ↑ Henry Marvin Wharton (1904), War Songs and Poems of the Southern Confederacy, 1861-1865, Philadelphia: The John C. Winston Co., p. 188. OCLC 9348166

- 1 2 Daniel E. Sutherland (1988), The Confederate Carpetbaggers, Louisiana State University Press, p. 4. ISBN 0-8071-1393-X

- 1 2 Elizabeth Young, (1999) Disarming the Nation: Women's Writing and the American Civil War, University of Chicago Press, p. 254. ISBN 0-226-96087-0

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Part 4, chapter 41

- 1 2 Part 2, chapter 11

- 1 2 Young, E., Disarming the Nation: women's writing and the American Civil War, p. 252