Manihot walkerae

| Manihot walkerae | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| (unranked): | Angiosperms |

| (unranked): | Eudicots |

| (unranked): | Rosids |

| Order: | Malpighiales |

| Family: | Euphorbiaceae |

| Genus: | Manihot |

| Species: | M. walkerae |

| Binomial name | |

| Manihot walkerae Croizat[2] | |

Manihot walkerae, commonly known as Walker's manihot,[3] is a species of flowering plant in the spurge family, Euphorbiaceae, that is native to the Lower Rio Grande Valley of Texas in the United States and Tamaulipas in Mexico. The specific name honours amateur botanist Thelma Ratcliff (Mrs. E. J.) Walker, who discovered the type specimen near Mission and La Joya, Texas in 1942.[4]

Description

Manihot walkerae is a perennial herb or small shrub[5] that reaches a height of up to 0.5 m (1.6 ft).[6] The entire plant has an odor resembling hydrogen cyanide. Roots are carrot-shaped and tuberous, while stems are prostrate or ascending-erect. The peltate leaves are alternate, simple, glabrous, 5–14 cm (2.0–5.5 in) long and 4–11 cm (1.6–4.3 in) wide. They are palmately lobed, with 3-5 pandurate to halberd-shaped lobes. The white flowers occur in androgynous, axillary, subspicate racemes. The fruit is a dehiscent capsule 10–12 mm (0.39–0.47 in) in length.[5]

Habitat

Walker's manihot generally grows under the branches of larger shrubs and trees. In Texas, this species inhabits xeric slopes and uplands in thorny shrublands. Soils are shallow, calcareous sandy loams, often derived from the caliche and conglomerate of the Goliad Formation. Associated woody plants include Acacia rigidula, Citharexylum brachyanthum, Cylindropuntia leptocaulis, Karwinskia humboldtiana, Leucophyllum frutescens, and Prosopis glandulosa. Walker's manihot has been collected from the Loreto caliche sand plain in Tamaulipas, where it grew alongside Asclepias prostrata, Manfreda longiflora, and Physaria thamnophila.[5]

Conservation

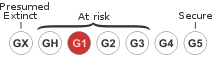

Manihot walkerae was added to the United States Endangered Species List on 2 October 1991 and the Texas Endangered Species List on 30 March 1993.[5] NatureServe considers it critically imperiled, as the wild population is estimated to be less than 1,000 plants.[1] Protected populations occur in the Lower Rio Grande Valley National Wildlife Refuge, while cultivated specimens exist at the San Antonio Botanical Garden, the University of Texas at Austin,[7] and Santa Ana National Wildlife Refuge.[4]

Uses

Walker's manihot is a close relative of the widely cultivated cassava (M. esculenta) and has been studied for its role in introducing valuable traits into the latter.[7] The tubers of M. walkerae exhibit dramatically delayed postharvest physiological deterioration (PPD). This trait can be passed to M. esculenta × M. walkerae hybrids,[8] allowing the roots to remain intact 1 month after harvest.[9]

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Manihot walkerae. |

| Wikispecies has information related to: Manihot walkerae |

- 1 2 "Manihot walkerae - Croizat Walker's Manihot". NatureServe Explorer. NatureServe. Retrieved 2011-05-07.

- ↑ "Taxon: Manihot walkerae Croizat". Germplasm Resources Information Network. United States Department of Agriculture. 1995-01-26. Retrieved 2011-05-07.

- ↑ "Manihot walkerae". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 2011-05-07.

- 1 2 Mild, Christina (2003). "Manihot walkerae" (PDF). Rio Delta Wild. Retrieved 2011-05-07.

- 1 2 3 4 Poole, Jackie M.; William R. Carr; Dana M. Price; Jason R. Singhurst (2007). Rare Plants of Texas: a Field Guide. Texas A&M University Press. pp. 306–307. ISBN 978-1-58544-557-8.

- ↑ Everitt, J. H.; Dale Lynn Drawe; Robert I. Lonard (2002). Trees, Shrubs, and Cacti of South Texas. Texas Tech University Press. p. 218. ISBN 978-0-89672-473-0.

- 1 2 Barrett, Cindy (2010-03-04). "Manihot walkerae". CPC National Collection Plant Profiles. Center for Plant Conservation. Retrieved 2011-05-07.

- ↑ Ceballos, Hernán; Okogbenin, Emmanuel; Pérez, Juan Carlos; Becerra López-Valle, Luis Augusto; Debouck, Daniel (2010). "Chapter 2: Cassava". Root and Tuber Crops. Handbook of Plant Breeding. 7. Springer. pp. 53–96. doi:10.1007/978-0-387-92765-7_2.

- ↑ Lokko, Y.; E. Okogbenin; C. Mba; A. Dixon; A. Raji; M. Fregene (2007). "Chapter 14: Cassava". Pulses, Sugar and Tuber Crops. Genome Mapping and Molecular Breeding in Plants. 3. Springer. p. 263. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-34516-9_14.