Pope Leo XIII

| Pope Leo XIII | |

|---|---|

Pope Leo XIII | |

| Papacy began | 20 February 1878 |

| Papacy ended | 20 July 1903 |

| Predecessor | Pius IX |

| Successor | Pius X |

| Orders | |

| Ordination |

31 December 1837 by Carlo Odescalchi |

| Consecration |

19 February 1843 by Luigi Emmanuele Nicolò Lambruschini |

| Created Cardinal |

19 December 1853 by Pius IX |

| Personal details | |

| Birth name | Vincenzo Gioacchino Raffaele Luigi Pecci |

| Born |

2 March 1810 Carpineto Romano, département of Rome, French Empire |

| Died |

20 July 1903 (aged 93) Apostolic Palace, Rome, Vatican City |

| Previous post |

|

| Coat of arms |

|

| Other popes named Leo | |

| Papal styles of Pope Leo XIII | |

|---|---|

| |

| Reference style | His Holiness |

| Spoken style | Your Holiness |

| Religious style | Holy Father |

| Posthumous style | None |

| Ordination history of Pope Leo XIII | |

|---|---|

Priestly ordination | |

| Ordained by | Carlo Odescalchi |

| Date of ordination | 31 December 1837 |

Episcopal consecration | |

| Principal consecrator | Luigi Lambruschini |

| Co-consecrators |

Fabio Maria Asquini Giuseppe Maria Castellani |

| Date of consecration | 19 February 1843 |

Cardinalate | |

| Elevated by | Pius IX |

| Date of elevation | 19 December 1853 |

Bishops consecrated by as principal consecrator | |

| Antonio Briganti | 19 November 1871 |

| Carmelo Pascucci | 19 November 1871 |

| Carlo Laurenzi | 24 June 1877 |

| Edoardo Borromeo | 19 May 1878 |

| Francesco Latoni | 1 June 1879 |

| Jean Baptiste François Pitra | 1 June 1879 |

| Bartholomew Woodlock | 1 June 1879 |

| Agostino Bausa | 24 March 1889 |

| Giuseppe Antonio Ermenegildo Prisco | 29 May 1898 |

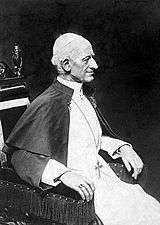

Pope Leo XIII (Italian: Leone XIII), (born Vincenzo Gioacchino Raffaele Luigi Pecci;[lower-alpha 1] 2 March 1810 – 20 July 1903, to an Italian comital family,) reigned as Pope from 20 February 1878 to his death in 1903. He was the oldest pope (reigning until the age of 93), and had the third longest pontificate, behind that of Pius IX (his immediate predecessor) and John Paul II. He is the most recent pontiff to date to take the pontifical name of "Leo" upon being elected to the pontificate.

He is well known for his intellectualism, the development of social teachings with his famous papal encyclical Rerum novarum and his attempts to define the position of the Catholic Church with regard to modern thinking. He influenced Roman Catholic Mariology and promoted both the rosary and the scapular.

Leo XIII issued a record of eleven Papal encyclicals on the rosary earning him the title as the "Rosary Pope". In addition, he approved two new Marian scapulars and was the first pope to fully embrace the concept of Mary as Mediatrix. He was the first pope to never have held any control over the Papal States, after they were dissolved by 1870. He died on 20 July 1903 at the age of 93 and was briefly buried in the grottos of Saint Peter's Basilica before his remains were later transferred to the Basilica of Saint John Lateran.

Early life

Born in Carpineto Romano, near Rome, he was the sixth of the seven sons of Count Ludovico Pecci and his wife Anna Prosperi Buzzi. His brothers included Giuseppe and Giovanni Battista Pecci. Until 1818 he lived at home with his family, "in which religion counted as the highest grace on earth, as through her, salvation can be earned for all eternity".[1] Together with his brother Giuseppe, he studied in the Jesuit College in Viterbo, where he stayed until 1824.[2] He enjoyed the Latin language and was known to write his own Latin poems at the age of eleven.

In 1824 he and his older brother Giuseppe were called to Rome where their mother was dying. Count Pecci wanted his children near him after the loss of his wife, and so they stayed with him in Rome, attending the Jesuit Collegium Romanum. In 1828, Giuseppe entered the Jesuit order, while Vincenzo decided in favour of secular clergy.[3]

He studied at the Academia dei Nobili, mainly diplomacy and law. In 1834 he gave a student presentation, attended by several cardinals, on papal judgements. For his presentation he received awards for academic excellence, and gained the attention of Vatican officials.[4] Cardinal Secretary of State Luigi Lambruschini introduced him to Vatican congregations. During a cholera epidemic in Rome he ably assisted Cardinal Sala in his duties as overseer of all the city hospitals.[5] Pope Gregory XVI appointed Pecci on 14 February 1837, as personal prelate even before he was ordained priest on 31 December 1837, by the Vicar of Rome, Cardinal Carlo Odescalchi. He celebrated his first mass together with his priest brother Giuseppe.[6] He received his doctorate in theology in 1836 and doctorates of civil and Canon Law in Rome also.

Provincial administrator

Shortly thereafter, Gregory XVI appointed Pecci as legate (provincial administrator) to Benevento. The smallest of papal provinces, Benevento included about 20,000 people.[5]

The main problems facing Pecci were a decaying local economy, insecurity because of widespread bandits, and pervasive Mafia structures, who often were allied with aristocratic families. Pecci arrested the most powerful aristocrat in Benevento, and his troops captured others, who were either killed or imprisoned by him. With the public order restored, he turned to the economy and a reform of the tax system to stimulate trade with neighboring provinces.[7]

Monsignor Pecci was first destined for Spoleto, a province with 100,000, but on 17 July 1841, he was sent to Perugia with 200,000 inhabitants.[5]

His immediate concern was to prepare the province for a papal visitation in the same year. Pope Gregory XVI visited hospitals and educational institutions for several days, asking for advice and listing questions. The fight against corruption continued in Perugia, where Pecci himself investigated several incidents. When it was claimed that a bakery was selling bread below the prescribed pound weight, he personally went there, had all bread weighed, and confiscated it if below legal weight. The confiscated bread was distributed to the poor.[8]

Nuncio to Belgium

In 1843, Pecci, only thirty-three years old, was appointed Apostolic Nuncio to Belgium,[9] a position which guaranteed the Cardinal's hat after completion of the tour.

On 27 April 1843, Pope Gregory XVI appointed Pecci Archbishop and asked his Cardinal Secretary of State Lambruschini to consecrate him.[9] Pecci developed excellent relations with the royal family and used the location to visit neighbouring Germany, where he was particularly interested in the resumed construction of the Cologne Cathedral.

Upon his initiative, a Belgian College in Rome was opened in 1844, where 102 years later, in 1946, Pope John Paul II would begin his Roman studies. He spent several weeks in England with Bishop Nicholas Wiseman, carefully reviewing the condition of the Catholic Church in that country.[10]

In Belgium, the school question was then sharply debated between the Catholic majority and the Liberal minority. Pecci encouraged the struggle for Catholic schools, yet he was able to win the good will of the Court, not only of the pious Queen Louise, but also of King Leopold I, strongly Liberal in his views. The new nuncio succeeded in uniting the Catholics.

At the end of his mission he was granted by the King the Grand Cordon in the Order of Leopold.[11]

Archbishop of Perugia

Papal assistant

Pecci was named papal assistant in 1843. He first achieved note as a popular and successful Archbishop of Perugia from 1846 to 1877. After Pope Pius IX granted unlimited freedom for the press in the Papal States in 1847,[12] Pecci, who had been highly popular in the first years of his episcopate, became the object of attacks in the media and at his residence.[13] In 1848, revolutionary movements developed throughout Western Europe, including France, Germany and Italy. Austrian, French and Spanish troops reversed the revolutionary gains, but at a price for Pecci and the Catholic Church, who could not regain their former popularity.

Provincial council

Pecci called a provincial council to reform the religious life in his dioceses. He invested in enlarging the seminary for future priests and in hiring new and prominent professors, preferably Thomists. He called on his brother Giuseppe Pecci, a noted Thomist scholar, to resign his professorship in Rome and teach in Perugia instead.[14] His own residence was next to the seminary, which facilitated his daily contacts with the students.

Charitable activities

Pecci developed several activities in support of Catholic charities. He founded homes for homeless boys and girls and for elderly women. Throughout his dioceses he opened branches of a Bank, Monte di Pietà, which focused on low-income people and provided low interest loans.[15] He created soup kitchens, which were run by the Capuchins. In the consistory of 19 December 1853, he was elevated to the College of Cardinals, as Cardinal-Priest of S. Crisogono.[9] In light of continuing earthquakes and floods, he donated all resources for festivities to the victims. Much of the public attention turned on the conflict between the Papal States and Italian nationalism, aiming at these states' annihilation so as to achieve the Unification of Italy.

Defence of the papacy

Pecci defended the papacy and its claims. When Italian authorities expropriated convents and monasteries of Catholic orders, turning them into administration or military buildings, Cardinal Pecci protested but acted moderately. When the Italian state took over Catholic schools, Pecci, fearing for his theological seminary, simply added all secular topics from other schools and opened the seminary to non-theologians.[16] The new government, in addition to the expropriations, levied taxes on the Church and issued legislation according to which all Episcopal or papal utterances were to be approved by the government before their publication.[17]

Organizing the First Vatican Council

Pope Pius IX announced an ecumenical council, which became known as the First Vatican Council, to take place in the Vatican on 8 December 1869. Pecci was likely to be well informed, since his brother Giuseppe had been named by the Pope to help prepare this event.

In his last years in Perugia, Pecci several times addressed the role of the Church in modern society. Pecci defined the Church as the mother of material civilization, because the Church upholds human dignity of working people, opposes the excesses of industrialization, and has developed large scale charities for the needy.[18]

In August 1877, on the death of Cardinal Filippo de Angelis, Pope Pius IX appointed him Camerlengo, so that he was obliged to reside in Rome.[19]

Papal conclave

Pope Pius IX died on 7 February 1878,[19] and during his closing years the Liberal press had often insinuated that the Italian Government should take a hand in the conclave and occupy the Vatican. However the Russo-Turkish War and the sudden death of Victor Emmanuel II (9 January 1878) distracted the attention of the government.

In the conclave, the questions that the cardinals faced varied and issues discussed included church-state relations in Europe specifically with Italy, divisions in the church, and the status of the First Vatican Council. It was also debated that the conclave be moved somewhere else but it was Pecci that debated otherwise, and the conclave assembled in Rome on 18 February 1878. Cardinal Pecci was elected on the third ballot of the conclave and he chose the name of Leo XIII.[19] He was announced to the people and later crowned on 3 March 1878.

Papacy

| Part of a series on the |

| Catholic social teaching |

|---|

|

| Overview |

|

|

|

|

As soon as he was elected to the papacy, Leo XIII worked to encourage understanding between the Church and the modern world. When he firmly re-asserted the scholastic doctrine that science and religion co-exist, he required the study of Thomas Aquinas[20] and opened the Vatican Secret Archives to qualified researchers, among whom was the noted historian of the Papacy Ludwig von Pastor. He also re-founded the Vatican Observatory "so that everyone might see clearly that the Church and her Pastors are not opposed to true and solid science, whether human or divine, but that they embrace it, encourage it, and promote it with the fullest possible devotion."[21]

Leo XIII was the first Pope of whom a sound recording was made. The recording can be found on a compact disc of Alessandro Moreschi's singing; a recording of his praying of the Ave Maria is available on the Web.[22] He was also the first Pope to be filmed on the motion picture camera. He was filmed by its inventor, W. K. Dickson, and blessed the camera while being filmed.[23]

Leo XIII brought normality back to the Church after the tumultuous years of Pius IX. Leo's intellectual and diplomatic skills helped regain much of the prestige lost with the fall of the Papal States. He tried to reconcile the Church with the working class, particularly by dealing with the social changes that were sweeping Europe. The new economic order had resulted in the growth of an impoverished working class who had increasing anti-clerical and socialist sympathies. Leo helped reverse this trend.

While Leo XIII was no radical in either theology or politics, his papacy did move the Catholic Church back to the mainstream of European life. Considered a great diplomat, he managed to improve relations with Russia, Prussia, Germany, France, Britain and other countries.

Pope Leo XIII was able to reach several agreements in 1896 that resulted in better conditions for the faithful and additional appointments of bishops. During the Fifth cholera pandemic in 1891 he ordered the construction of a hospice inside the Vatican. That building would be torn down in 1996 to make way for construction of the Domus Sanctae Marthae.[24]

Leo was a Vin Mariani drinker. He awarded a Vatican gold medal to the wine, and also appeared on a poster endorsing it.[25]

His favorite poets were Virgil and Dante.[26]

Foreign relations

Russia

Pope Leo XIII began his pontificate with a friendly letter to Tzar Alexander II, in which he reminded the Russian monarch of the millions of Catholics living in his empire who would like to be good Russian subjects, provided their dignity were respected.

After the assassination of Alexander II, the Pope sent a high ranking representative to the coronation of his successor. Alexander III was grateful and asked for all religious forces to unify. He asked the Pope to ensure that his bishops abstain from political agitation. Relations improved further, when Pope Leo XIII, due to Italian considerations, distanced the Vatican from the Rome-Vienna-Berlin alliance and helped to facilitate a rapprochement between Paris and St. Petersburg.

Germany

Under Otto von Bismarck, the anti-Catholic Kulturkampf in Prussia led to significant restrictions on the Catholic Church in Imperial Germany, including the Jesuits Law of 1872. During Leo's papacy compromises were informally reached and the anti-Catholic attacks subsided.[27]

The Centre Party in Germany represented Catholic interests and was a positive force for social change. It was encouraged by Leo's support for social welfare legislation and the rights of working people. Leo's forward-looking approach encouraged Catholic Action in other European countries where the social teachings of the Church were incorporated into the agenda of Catholic parties, particularly the Christian democratic parties, which became an acceptable alternative to socialist parties. Leo's social teachings were reiterated throughout the 20th century by his successors.

In his Memoirs[28] Kaiser Wilhelm II discussed the "friendly, trustful relationship that existed between me and Pope Leo XIII." During Wilhelm's third visit to Leo: "It was of interest to me that the Pope said on this occasion that Germany must be the sword of the Catholic Church. I remarked that the old Roman Empire of the German nation no longer existed, and that conditions had changed. But he adhered to his words."

France

Leo XIII was the first pope to come out strongly in favour of the French Republic, upsetting many French monarchists.

Italy

In light of climate hostile to the Church, Leo continued the policies of Pius IX towards Italy, without major modifications.[29] In his relations with the Italian state, Leo XIII continued the Papacy's self-imposed incarceration in the Vatican stance, and continued to insist that Italian Catholics should not vote in Italian elections or hold elected office. In his first consistory in 1879 he elevated his older brother Giuseppe to the cardinalate. He had to defend the freedom of the Church against what Catholics considered Italian persecutions and attacks in the area of education, expropriation and violation of Catholic Churches, legal measures against the Church and brutal attacks, culminating in anticlerical groups attempting to throw the body of the deceased Pope Pius IX into the Tiber river on 13 July 1881.[30] The Pope even considered moving his residence to Trieste or Salzburg, two cities in Austria, an idea which the Austrian monarch Franz Josef I gently rejected.[31]

United Kingdom

Among the activities of Leo XIII that were important for the English-speaking world, he restored the Scottish hierarchy in 1878. In the following year, on 12 May 1879, raised to the rank of cardinal the convert clergyman John Henry Newman, who was to be beatified by Pope Benedict XVI in 2010. In British India, too, Leo established a Catholic hierarchy in 1886, and regulated some long-standing conflicts with the Portuguese authorities. A Papal Rescript (20 April 1888) condemned the Irish Plan of Campaign and all clerical involvement in it as well as boycotting, followed in June by the Papal encyclical "Saepe Nos"[32] that was addressed to all the Irish bishops. Of outstanding significance, not least for the English-speaking world, was Leo's encyclical Apostolicae Curae on the invalidity of the Anglican orders, published in 1896.

United States

The United States at many moments in time attracted the attention and admiration of Pope Leo. He confirmed the decrees of the Third Plenary Council of Baltimore (1884), and raised James Gibbons, archbishop of that city, to the cardinalate in 1886.

American newspapers criticized Pope Leo because they claimed that he was attempting to gain control of American public schools. One cartoonist drew Leo as a fox unable to reach grapes that were labeled for American schools; the caption read "Sour grapes!"[33]

Brazil

Pope Leo XIII is also remembered for the First Plenary Council of Latin America held at Rome in 1899, and his encyclical of 1888 to the bishops of Brazil on the abolition of slavery. In 1897, he published the Apostolic Letter Trans Oceanum, which dealt with the privileges and ecclesiastical structure of the Catholic Church in Latin America.[34]

Chile

His role in South America will also be remembered, especially the pontifical benediction extended over Chilean troops on the eve of the Battle of Chorrillos during the War of the Pacific in January 1881. The Chilean soldiers thus blessed then looted the cities of Chorrillos and Barranco, including the churches, and their Chaplains headed the robbery at the Biblioteca Nacional del Perú, where the soldiers ransacked various items along with much capital, and Chilean Priests coveted rare and ancient editions of the Bible that were stored there.[35] Despite this, one year later Chilean President Domingo Santa Marìa issued the Laicist Laws, which separated the Church from the State, considered a slap in the face for the papacy.

Evangelization

Pope Leo XIII sanctioned the missions to eastern Africa. In 1879 Catholic missionaries associated with the White Father Congregation (Society of the Missionaries of Africa) came to Uganda and others went to Tanganyika (present day Tanzania) and Rwanda. In 1887 he approved the foundation of Missionaries of St. Charles which was organized by the Bishop of Piacenza, John Baptist Scalabrini. The missionaries were sent to America to do pastoral care for the Italian Immigrants often victims by labor exploitation.

Theology

The pontificate of Leo XIII was theologically influenced by the First Vatican Council (1869–1870), which had ended only eight years earlier. Leo XIII issued some 46 apostolic letters and encyclicals dealing with central issues in the areas of marriage and family and state and society. He also wrote two prayers for the intercession of Michael the Archangel after having a vision of Michael and the end times.[37]

Thomism

As pope, he used all his authority for a revival of Thomism, the theology of Thomas Aquinas. On 4 August 1879, Leo XIII promulgated the encyclical Aeterni Patris (“Eternal Father”) which, more than any other single document, provided a charter for the revival of Thomism—the medieval theological system based on the thought of Aquinas—as the official philosophical and theological system of the Catholic Church. It was to be normative not only in the training of priests at church seminaries but also in the education of the laity at universities.

Following this encyclical Pope Leo XIII created the Pontifical Academy of St. Thomas Aquinas on October 15, 1879 and ordered the publication of the critical edition, the so-called Leonine Edition, of the complete works of the doctor angelicus. The superintendence of the leonine edition was entrusted to Tommaso Maria Zigliara, professor and rector of the Collegium Divi Thomae de Urbe the future Pontifical University of Saint Thomas Aquinas, Angelicum. Leo XIII also founded the Angelicum's Faculty of Philosophy in 1882 and its Faculty of Canon Law in 1896.

Consecrations

Pope Leo XIII performed a number of consecrations, at times entering new theological territory. After he received many letters from Sister Mary of the Divine Heart, the countess of Droste zu Vischering and Mother Superior in the Convent of the Congregation of the Good Shepherd Sisters in Porto, Portugal, asking him to consecrate the entire world to the Sacred Heart of Jesus, he commissioned a group of theologians to examine the petition on the basis of revelation and sacred tradition. The outcome of this investigation was positive, and so in the encyclical letter Annum sacrum (on May 25, 1899) he decreed that the consecration of the entire human race to the Sacred Heart of Jesus should take place on June 11, 1899.

The encyclical letter also encouraged the entire Roman Catholic episcopate to promote the First Friday Devotions, established June as the Month of the Sacred Heart, and included the Prayer of Consecration to the Sacred Heart.[39] His consecration of the entire world to the Sacred Heart of Jesus presented theological challenges in consecrating non-Christians. Since about 1850, various congregations and States had consecrated themselves to the Sacred Heart, and, in 1875, this consecration was made throughout the Catholic world.

Scriptures

In his 1893 encyclical Providentissimus Deus, he described the importance of scriptures for theological study. It was an important encyclical for Catholic theology and its relation to the Bible, as Pope Pius XII pointed out fifty years later in his encyclical Divino Afflante Spiritu.[40]

Ecumenical efforts

Pope Leo XIII fostered ecumenical relations, particularly with the East. He opposed efforts to Latinize the Eastern Rite Churches, stating that they constitute a most valuable ancient tradition and symbol of the divine unity of the Catholic Church.

Theological research

Leo XIII is credited with great efforts in the areas of scientific and historical analysis. He opened the Vatican Archives and personally fostered a twenty-volume comprehensive scientific study of the Papacy by Ludwig von Pastor, an Austrian historian.[41]

Mariology

His predecessor, Pope Pius IX, became known as the Pope of the Immaculate Conception because of the dogmatization in 1854. Leo XIII, in light of his unprecedented promulgation of the rosary in eleven encyclicals, was called the Rosary Pope. In eleven encyclicals on the rosary he promulgates Marian devotion. In his encyclical on the fiftieth anniversary of the Dogma of the Immaculate Conception, he stresses her role in the redemption of humanity, mentioning Mary as Mediatrix and Co-Redemptrix.

Social teachings

Church and state

Leo XIII worked to encourage understanding between the Church and the modern world, though he preferred a cautious view on freedom of thought, stating that it "is quite unlawful to demand, defend, or to grant unconditional freedom of thought, or speech, of writing or worship, as if these were so many rights given by nature to man". Leo's social teachings are based on the Catholic premise that God is the Creator of the world and its Ruler. Eternal law commands the natural order to be maintained, and forbids that it be disturbed; men's destiny is far above human things and beyond the earth.

Rerum novarum

His encyclicals changed the Church's relations with temporal authorities, and, in the 1891 encyclical Rerum novarum, for the first time addressed social inequality and social justice issues with Papal authority, focusing on the rights and duties of capital and labour. He was greatly influenced by Wilhelm Emmanuel von Ketteler, a German bishop who openly propagated siding with the suffering working classes in his book Die Arbeiterfrage und das Christentum. Since Leo XIII, Papal teachings have expanded on the rights and obligations of workers and the limitations of private property: Pope Pius XI Quadragesimo anno, the Social teachings of Pope Pius XII on a huge range of social issues, John XXIII Mater et magistra in 1961, Pope Paul VI, the encyclical Populorum progressio on world development issues, and Pope John Paul II, Centesimus annus, commemorating the 100th anniversary of Rerum novarum. Leo XIII had argued that both capitalism and communism are flawed. Rerum novarum introduced the idea of subsidiarity, the principle that political and social decisions should be taken at a local level, if possible, rather than by a central authority, into Catholic social thought. A list of all of Leo's encyclicals can be found in the List of Encyclicals of Pope Leo XIII.

Canonizations and beatifications

Leo XIII canonized the following saints during his pontificate:

- 8 December 1881: Clare of Montefalco (d. 1308), John Baptist de Rossi (1696–1764), Lawrence of Brindisi (d. 1619), and Benedict Joseph Labre (1748–83)

- 15 January 1888: Seven Holy Founders of the Servite Order, Peter Claver (1581–1654), John Berchmans (1599–1621), and Alphonsus Rodriguez (1531–1617)

- 27 May 1897: Antonio Maria Zaccaria (1502–39) and Peter Fourier (1565–1640)

- 24 May 1900: John Baptist de la Salle (1651–1719) and Rita of Cascia (1381–1457)

Leo XIII also beatified several of his predecessors: Urban II (14 July 1881), Victor III (23 July 1887) and Innocent V (9 March 1898). He also canonized Adrian III on 2 June 1891.

He also beatified Giancarlo Melchiori on 22 January 1882, Giovanni Giovenale Ancina on 9 February 1890, Inés of Benigánim on 26 February 1888, Pompilio Maria Pirrotti on 26 January 1890, Leopoldo Croci on 12 May 1893, Antonio Baldinucci on 16 April 1893, Rodolfo Acquaviva and 4 Companions on 30 April 1893, Diego José López-Caamaño on 22 April 1894, Antonio Maria Zaccaria (whom he later canonized) on 3 January 1890, John Baptist de la Salle (whom he later canonized) on 19 February 1888, Maria Maddalena Martinengo on 3 June 1900, Dénis Berthelot of the Nativity and Redento Rodríguez of the Cross on 10 June 1900, Antonio Grassi on 30 September 1900, Gerard Majella in 1893, both Edmund Campion and Ralph Sherwin in 1886, Bernardino Realino on 12 January 1896, and Jeanne de Lestonnac on 23 September 1900. He also approved the cult of Cosmas of Aphrodisia. He also beatified several of the English martyrs in 1895.[42]

Audiences

One of the first audiences Leo XIII granted was to the professors and students of the Collegio Capranica, where in the first row knelt in front of him a young seminarian, Giacomo Della Chiesa, his eventual successor Pope Benedict XV, who would reign from 1914 to 1922.

While on a pilgrimage with her father and sister in 1887, the future Saint Thérèse of Lisieux attended a general audience with Pope Leo XIII and asked him to allow her to enter the Carmelite order. Even though she was strictly forbidden to speak to him because she was told it would prolong the audience too much, in her autobiography, Story of a Soul, she wrote that after she kissed his slipper and he presented his hand, instead of kissing it, she took it in her own hand and said through tears, "Most Holy Father, I have a great favor to ask you. In honor of your Jubilee, permit me to enter Carmel at the age of 15!" Leo XIII answered, "Well, my child, do what the superiors decide." Thérèse replied, "Oh! Holy Father, if you say yes, everybody will agree!" Finally, the Pope said, "Go... go... You will enter if God wills it" [italics hers] after which time two guards lifted Thérèse (still on her knees in front of the Pope) by her arms and carried her to the door where a third gave her a medal of the Pope. Shortly thereafter, the Bishop of Bayeux authorized the prioress to receive Thérèse, and in April 1888, she entered Carmel at the age of 15.

Death

Leo XIII was the first pope to be born in the 19th century and was also the first to die in the 20th century: he lived to the age of 93, dying on 20 July 1903,[43] the longest-lived pope. At the time of his death, Leo XIII was the second-longest reigning pope, exceeded only by his immediate predecessor, Pius IX.

Leo XIII was entombed in St. Peter's Basilica only very briefly after his funeral, but was later moved instead to the very ancient basilica of St. John Lateran, his cathedral church as the Bishop of Rome, and a church in which he took a particular interest. He was moved there in 1924.

See also

- Cardinals created by Leo XIII

- Distributism

- Prayer to Saint Michael

- Taxil hoax

- Restoration of the Scottish hierarchy

Notes

- ↑ English: Vincent Joachim Raphael Lewis Pecci

- ↑ Kühne 1880, p. 7.

- ↑ Kühne 1880, p. 12.

- ↑ Kühne 1880, p. 20.

- ↑ Kühne 1880, p. 23.

- 1 2 3 Benigni, Umberto. "Pope Leo XIII." The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 9. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1910. 28 Aug. 2014

- ↑ Kühne 1880, p. 24.

- ↑ Kühne 1880, p. 31.

- ↑ Kühne 1880, p. 37.

- 1 2 3 Miranda, Salvador. "Pecci, Gioacchino", ''The Cardinals of the Holy Roman Church

- ↑ Kühne 1880, p. 52.

- ↑ Laatste Nieuws (Het) 01-01-1910

- ↑ Kühne 62

- ↑ Kühne 1880, p. 66.

- ↑ Kühne 1880, p. 76.

- ↑ Kühne 1880, p. 78.

- ↑ Kühne 1880, p. 102.

- ↑ Kühne 1880, p. 105.

- ↑ Kühne 1880, p. 129.

- 1 2 3 O'Reilly, Bernard. Life of Leo XIII, Charles L. Webster & Company, New York, 1887

- ↑ Aeterni Patris – On the Restoration of Christian Philosophy (encyclical), Catholic forum.

- ↑ Pecci, Vincenzo Gioacchino Raffaele Luigi (March 14, 1891), Ut Mysticam (in Latin).

- ↑ Pope Leo XIII, 1810–1910, Archive.

- ↑ Abel, Richard, Encyclopedia of early cinema, p. 266, ISBN 0-415-23440-9.

- ↑ "Domus Sanctae Marthae & The New Urns Used in the Election of the Pope". EWTN. 22 February 1996. Retrieved 15 February 2010.

- ↑ Inciardi, James A. (1992). The War on Drugs II. Mayfield Publishing Company. p. 6. ISBN 1-55934-016-9.

- ↑ "Pope Leo XIII and his Household" in The Century Illustrated Monthly Magazine, p. 596

- ↑ Ross, Ronald J. (1998). The failure of Bismarck's Kulturkampf: Catholicism and state power in imperial Germany, 1871–1887. Washington: Catholic University of America Press. ISBN 0-81320894-7.

- ↑ Memoirs. pp. 204–7. Retrieved 2013-06-23.

- ↑ Schmidlin 1934, p. 409.

- ↑ Schmidlin 1934, p. 413.

- ↑ Schmidlin 1934, p. 414.

- ↑ Pecci, Vincenzo Gioacchino Raffaele Luigi, Sæpe nos (in Latin), New Advent.

- ↑ http://www.criaimages.com/detail.aspx?img=0000037708c

- ↑ Pecci, Vincenzo Gioacchino Raffaele Luigi (1897-04-18). "Trans Oceanum, Litterae apostolicae, De privilegiis Americae Latinae" [Over the Ocean, Apostolic letter on Latin American privileges] (in Latin). Rome, IT: Vatican. Retrieved 2013-06-23.

- ↑ Caivano, Tomas (1907), Historia de la guerra de América entre Chile, Perú y Bolivia [History of the American war between Chile, Peru and Bolivia] (in Spanish).

- ↑ Kühne, Benno (1880), Unser Heiliger Vater Papst Leo XIII in seinem Leben und wirken, Benzinger: Einsiedeln, p. 247.

- ↑ "Archangel Michael", Queen of Angels Foundation

- ↑ Chasle, Louis (1906), Sister Mary of the Divine Heart, Droste zu Vischering, religious of the Good Shepherd, 1863–1899, London: Burns & Oates.

- ↑ Ball, Ann (2003), Encyclopedia of Catholic Devotions and Practices, p. 166, ISBN 0-87973-910-X.

- ↑ Divino Afflante Spiritu, 1–12.

- ↑ von Pastor, Ludwig (1950), Errinnerungen (in German).

- ↑ "St. Cosmas — Saints & Angels". Catholic Online. Retrieved 15 February 2010.

- ↑ John-Peter Pham, Heirs of the Fisherman : Behind the Scenes of Papal Death and Succession, (Oxford University Press, 2004), 98.

References

In English

- Duffy, Eamon (1997), Saints and Sinners, A History of the Popes, Yale University Press.

- Thérèse of Lisieux (1996), Story of a Soul — The Autobiography of St. Thérèse of Lisieux, Clarke, John Clarke trans (3rd ed.), Washington, DC: ICS.

- Quardt, Robert, The Master Diplomat; From the Life of Leo XIII, Wolson, Ilya trans, New York: Alba House.

- O'Reilly, Bernard (1887), Life of Leo XIII — From An Authentic Memoir — Furnished By His Order, New York: Charles L Webster & Co.

In German

- Bäumer, Remigius (1992), Marienlexikon [Dictionary of Mary] (in German), et al, St Ottilien, Eos.

- Franzen, August; Bäumer, Remigius (1988), Papstgeschichte (in German), Freiburg: Herder.

- Kühne, Benno (1880), Papst Leo XIII [Pope Leo XIII] (in German), New York & St. Louis: C&N Benzinger, Einsideln.

- Quardt, Robert (1964), Der Meisterdiplomat [The Master Diplomat] (in German), Kevelaer, DE: Butzon & Bercker

- Schmidlin, Josef (1934), Papstgeschichte der neueren Zeit (in German), München.

In Italian

- Regoli, Roberto (2009). "L'elite cardinalizia dopo la fine dello stato pontificio". Archivum Historiae Pontificiae. 47: 63–87. JSTOR 23565185. (registration required (help)).

-

Wikisource has the text of the 1913 Catholic Encyclopedia article Pope Leo XIII.

Further reading

- Richard H. Clarke (1903), The Life of His Holiness Leo XIII, Philadelphia: P. W. Ziegler & Co.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Leo XIII. |

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Leo XIII |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Pope Leo XIII |

- Pecci, Vincenzo Gioacchino Raffaele Luigi, Encyclicals and other documents (Etexts).

- Pope Leo XIII (texts & biography), Vatican City: The Vatican.

- Pope Leo XIII, overview of pontificate, Catholic forum.

- Pope Leo XIII (text with concordances and frequency list), Intra text.

- Works by or about Pope Leo XIII at Internet Archive

- Works by Pope Leo XIII at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Life and Acts of Pope Leo XII (1883), Archive.

- Pope Leo XIII at Find a Grave

- Keller, Joseph Edward. The Life and Acts of Pope Leo XIII, Benziger, 1882

| Diplomatic posts | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Raffaele Fornari |

Apostolic Nuncio to Belgium 1843–1846 |

Succeeded by Innocenzo Ferrieri |

| Catholic Church titles | ||

| Preceded by Giovanni Giacomo Sinibaldi |

— TITULAR — Archbishop of Tamiathis 1843–1846 |

Succeeded by Diego Planeta |

| Preceded by Carlo Filesio Cittadini |

Archbishop1-Bishop of Perugia 1846–1878 |

Succeeded by Federico Pietro Foschi |

| Preceded by Filippo de Angelis |

Camerlengo of the Holy Roman Church 22 September 1877–20 February 1878 |

Succeeded by Camillo di Pietro |

| Preceded by Pius IX |

Pope 20 February 1878–20 July 1903 |

Succeeded by Pius X |

| Notes and references | ||

| 1. Retained Personal Title | ||