G. K. Chesterton

| G. K. Chesterton | |

|---|---|

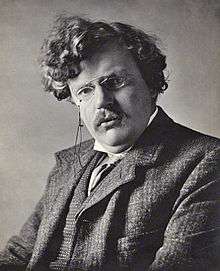

G. K. Chesterton, by E. H. Mills, 1909. | |

| Born |

Gilbert Keith Chesterton 29 May 1874 Kensington, London, England |

| Died |

14 June 1936 (aged 62) Beaconsfield, Buckinghamshire, England |

| Resting place | Roman Catholic Cemetery, Beaconsfield |

| Occupation | Journalist, novelist, essayist |

| Language | English |

| Citizenship | British |

| Education | St Paul's School (London) |

| Alma mater | Slade School of Art |

| Period | 1900–1936 |

| Genre | Essays, Fantasy, Christian apologetics, Catholic apologetics, Mystery, poetry |

| Literary movement | Catholic literary revival[1] |

| Notable works | The Napoleon of Notting Hill (1904), Charles Dickens: A Critical Study (1906), The Man Who Was Thursday (1908), Orthodoxy (1908), Father Brown stories (1910–1935), The Everlasting Man (1925) |

| Spouse | Frances Blogg |

| Relatives | Cecil Chesterton (brother) |

|

| |

| Signature |

|

Gilbert Keith Chesterton, KC*SG (29 May 1874 – 14 June 1936), better known as G. K. Chesterton, was an English writer,[2] poet, philosopher, dramatist, journalist, orator, lay theologian, biographer, and literary and art critic. Chesterton is often referred to as the "prince of paradox".[3] Time magazine has observed of his writing style: "Whenever possible Chesterton made his points with popular sayings, proverbs, allegories—first carefully turning them inside out."[4]

Chesterton is well known for his fictional priest-detective Father Brown,[5] and for his reasoned apologetics. Even some of those who disagree with him have recognised the wide appeal of such works as Orthodoxy and The Everlasting Man.[4][6] Chesterton, as a political thinker, cast aspersions on both Progressivism and Conservatism, saying, "The whole modern world has divided itself into Conservatives and Progressives. The business of Progressives is to go on making mistakes. The business of the Conservatives is to prevent the mistakes from being corrected."[7] Chesterton routinely referred to himself as an "orthodox" Christian, and came to identify this position more and more with Catholicism, eventually converting to Catholicism from High Church Anglicanism. George Bernard Shaw, Chesterton's "friendly enemy" according to Time, said of him, "He was a man of colossal genius."[4] Biographers have identified him as a successor to such Victorian authors as Matthew Arnold, Thomas Carlyle, Cardinal John Henry Newman, and John Ruskin.[8]

Early life

Chesterton was born in Campden Hill in Kensington, London, the son of Marie Louise, née Grosjean, and Edward Chesterton.[9][10] He was baptised at the age of one month into the Church of England,[11] though his family themselves were irregularly practising Unitarians.[12] According to his autobiography, as a young man Chesterton became fascinated with the occult and, along with his brother Cecil, experimented with Ouija boards.[13]

Chesterton was educated at St Paul's School, then attended the Slade School of Art to become an illustrator. The Slade is a department of University College London, where Chesterton also took classes in literature, but did not complete a degree in either subject.

Family life

Chesterton married Frances Blogg in 1901; the marriage lasted the rest of his life. Chesterton credited Frances with leading him back to Anglicanism, though he later considered Anglicanism to be a "pale imitation". He entered full communion with the Catholic Church in 1922.[14]

Career

In 1896 Chesterton began working for the London publisher Redway, and T. Fisher Unwin, where he remained until 1902. During this period he also undertook his first journalistic work, as a freelance art and literary critic. In 1902 the Daily News gave him a weekly opinion column, followed in 1905 by a weekly column in The Illustrated London News, for which he continued to write for the next thirty years.

Early on Chesterton showed a great interest in and talent for art. He had planned to become an artist, and his writing shows a vision that clothed abstract ideas in concrete and memorable images. Even his fiction contained carefully concealed parables. Father Brown is perpetually correcting the incorrect vision of the bewildered folks at the scene of the crime and wandering off at the end with the criminal to exercise his priestly role of recognition and repentance. For example, in the story "The Flying Stars", Father Brown entreats the character Flambeau to give up his life of crime: "There is still youth and honour and humour in you; don't fancy they will last in that trade. Men may keep a sort of level of good, but no man has ever been able to keep on one level of evil. That road goes down and down. The kind man drinks and turns cruel; the frank man kills and lies about it. Many a man I've known started like you to be an honest outlaw, a merry robber of the rich, and ended stamped into slime."[15]

Chesterton loved to debate, often engaging in friendly public disputes with such men as George Bernard Shaw,[16] H. G. Wells, Bertrand Russell and Clarence Darrow.[17][18] According to his autobiography, he and Shaw played cowboys in a silent film that was never released.[19]

Visual wit

Chesterton was a large man, standing 6 feet 4 inches (1.93 m) and weighing around 20 stone 6 pounds (130 kg; 286 lb). His girth gave rise to a famous anecdote. During the First World War a lady in London asked why he was not "out at the Front"; he replied, "If you go round to the side, you will see that I am."[20] On another occasion he remarked to his friend George Bernard Shaw, "To look at you, anyone would think a famine had struck England." Shaw retorted, "To look at you, anyone would think you have caused it."[21] P. G. Wodehouse once described a very loud crash as "a sound like G. K. Chesterton falling onto a sheet of tin".[22]

Chesterton usually wore a cape and a crumpled hat, with a swordstick in hand, and a cigar hanging out of his mouth. He had a tendency to forget where he was supposed to be going and miss the train that was supposed to take him there. It is reported that on several occasions he sent a telegram to his wife Frances from some distant (and incorrect) location, writing such things as "Am in Market Harborough. Where ought I to be?" to which she would reply, "Home".[23] Because of these instances of absent-mindedness and of Chesterton being extremely clumsy as a child, there has been speculation that Chesterton had undiagnosed developmental coordination disorder or attention deficit disorder.[24]

Radio

In 1931, the BBC invited Chesterton to give a series of radio talks. He accepted, tentatively at first. However, from 1932 until his death, Chesterton delivered over 40 talks per year. He was allowed (and encouraged) to improvise on the scripts. This allowed his talks to maintain an intimate character, as did the decision to allow his wife and secretary to sit with him during his broadcasts.[25]

The talks were very popular. A BBC official remarked, after Chesterton's death, that "in another year or so, he would have become the dominating voice from Broadcasting House."[26]

Death and veneration

Chesterton died of congestive heart failure on the morning of 14 June 1936, at his home in Beaconsfield, Buckinghamshire. His last known words were a greeting spoken to his wife. The homily at Chesterton's Requiem Mass in Westminster Cathedral, London, was delivered by Ronald Knox on 27 June 1936. Knox said, "All of this generation has grown up under Chesterton's influence so completely that we do not even know when we are thinking Chesterton."[27] He is buried in Beaconsfield in the Catholic Cemetery. Chesterton's estate was probated at £28,389, approximately equivalent in 2012 terms to £1.3 million.[28]

Near the end of Chesterton's life, Pope Pius XI invested him as Knight Commander with Star of the Papal Order of St. Gregory the Great (KC*SG).[29] The Chesterton Society has proposed that he be beatified.[30] He is remembered liturgically on 13 June by the Episcopal Church, with a provisional feast day as adopted at the 2009 General Convention.[31]

Writing

Chesterton wrote around 80 books, several hundred poems, some 200 short stories, 4000 essays, and several plays. He was a literary and social critic, historian, playwright, novelist, Catholic theologian[32][33] and apologist, debater, and mystery writer. He was a columnist for the Daily News, The Illustrated London News, and his own paper, G. K.'s Weekly; he also wrote articles for the Encyclopædia Britannica, including the entry on Charles Dickens and part of the entry on Humour in the 14th edition (1929). His best-known character is the priest-detective Father Brown,[5] who appeared only in short stories, while The Man Who Was Thursday is arguably his best-known novel. He was a convinced Christian long before he was received into the Catholic Church, and Christian themes and symbolism appear in much of his writing. In the United States, his writings on distributism were popularised through The American Review, published by Seward Collins in New York.

Of his nonfiction, Charles Dickens: A Critical Study (1906) has received some of the broadest-based praise. According to Ian Ker (The Catholic Revival in English Literature, 1845–1961, 2003), "In Chesterton's eyes Dickens belongs to Merry, not Puritan, England" ; Ker treats Chesterton's thought in Chapter 4 of that book as largely growing out of his true appreciation of Dickens, a somewhat shop-soiled property in the view of other literary opinions of the time.

Chesterton's writings consistently displayed wit and a sense of humour. He employed paradox, while making serious comments on the world, government, politics, economics, philosophy, theology and many other topics.[34][35]

Views and contemporaries

Chesterton's writing has been seen by some analysts as combining two earlier strands in English literature. Dickens' approach is one of these. Another is represented by Oscar Wilde and George Bernard Shaw, whom Chesterton knew well: satirists and social commentators following in the tradition of Samuel Butler, vigorously wielding paradox as a weapon against complacent acceptance of the conventional view of things.

Chesterton's style and thinking were all his own, however, and his conclusions were often opposed to those of Oscar Wilde and George Bernard Shaw. In his book Heretics, Chesterton has this to say of Wilde: "The same lesson [of the pessimistic pleasure-seeker] was taught by the very powerful and very desolate philosophy of Oscar Wilde. It is the carpe diem religion; but the carpe diem religion is not the religion of happy people, but of very unhappy people. Great joy does not gather the rosebuds while it may; its eyes are fixed on the immortal rose which Dante saw."[36] More briefly, and with a closer approximation of Wilde's own style, he writes in Orthodoxy concerning the necessity of making symbolic sacrifices for the gift of creation: "Oscar Wilde said that sunsets were not valued because we could not pay for sunsets. But Oscar Wilde was wrong; we can pay for sunsets. We can pay for them by not being Oscar Wilde."

Chesterton and Shaw were famous friends and enjoyed their arguments and discussions. Although rarely in agreement, they both maintained good will toward and respect for each other. However, in his writing, Chesterton expressed himself very plainly on where they differed and why. In Heretics he writes of Shaw:

After belabouring a great many people for a great many years for being unprogressive, Mr. Shaw has discovered, with characteristic sense, that it is very doubtful whether any existing human being with two legs can be progressive at all. Having come to doubt whether humanity can be combined with progress, most people, easily pleased, would have elected to abandon progress and remain with humanity. Mr. Shaw, not being easily pleased, decides to throw over humanity with all its limitations and go in for progress for its own sake. If man, as we know him, is incapable of the philosophy of progress, Mr. Shaw asks, not for a new kind of philosophy, but for a new kind of man. It is rather as if a nurse had tried a rather bitter food for some years on a baby, and on discovering that it was not suitable, should not throw away the food and ask for a new food, but throw the baby out of window, and ask for a new baby.[37]

Shaw represented the new school of thought, modernism, which was rising at the time. Chesterton's views, on the other hand, became increasingly more focused towards the Church. In Orthodoxy he writes: "The worship of will is the negation of will... If Mr. Bernard Shaw comes up to me and says, 'Will something', that is tantamount to saying, 'I do not mind what you will', and that is tantamount to saying, 'I have no will in the matter.' You cannot admire will in general, because the essence of will is that it is particular."[38]

This style of argumentation is what Chesterton refers to as using 'Uncommon Sense' – that is, that the thinkers and popular philosophers of the day, though very clever, were saying things that were nonsensical. This is illustrated again in Orthodoxy: "Thus when Mr. H. G. Wells says (as he did somewhere), 'All chairs are quite different', he utters not merely a misstatement, but a contradiction in terms. If all chairs were quite different, you could not call them 'all chairs'."[39] Or, again from Orthodoxy:

The wild worship of lawlessness and the materialist worship of law end in the same void. Nietzsche scales staggering mountains, but he turns up ultimately in Tibet. He sits down beside Tolstoy in the land of nothing and Nirvana. They are both helpless – one because he must not grasp anything, and the other because he must not let go of anything. The Tolstoyan's will is frozen by a Buddhist instinct that all special actions are evil. But the Nietzscheite's will is quite equally frozen by his view that all special actions are good; for if all special actions are good, none of them are special. They stand at the crossroads, and one hates all the roads and the other likes all the roads. The result is – well, some things are not hard to calculate. They stand at the cross-roads.[40]

Another contemporary and friend from schooldays was Edmund Bentley, inventor of the clerihew. Chesterton himself wrote clerihews and illustrated his friend's first published collection of poetry, Biography for Beginners (1905), which popularised the clerihew form. Chesterton was also godfather to Bentley's son, Nicolas, and opened his novel The Man Who Was Thursday with a poem written to Bentley.

Charges of anti-Semitism

Chesterton faced accusations of anti-Semitism during his lifetime, as well as posthumously.[41] An early supporter of Captain Dreyfus, by 1906 he had turned into an anti-dreyfusard.[42] From the early 20th century, both his fictional and non-fictional work included caricatures of Jews, stereotyping them as greedy, cowardly, disloyal and communists.[43]

The Marconi scandal of 1912-13 brought issues of anti-Semitism into the political mainstream, on the basis that senior ministers in the Liberal government had secretly profited from advanced knowledge of deals regarding wireless telegraphy. Some of the key players were Jewish.[44] Historian Todd Edelman identifies Catholic writers as central critics:

- "The most virulent attacks in the Marconi affair were launched by Hilaire Belloc and the brothers Cecil and G. K. Chesterton, whose hostility to Jews was linked to their opposition to liberalism, their backward-looking Catholicism, and the nostalgia for a medieval Catholic Europe that they imagined was ordered, harmonious, and homogeneous. The Jew baiting at the time of The Boer War and the Marconi scandal was linked to a broader protest, mounted in the main by the Radical wing of the Liberal Party, against the growing visibility of successful businessmen in national life and the challenges. What were seen as traditional English values.[45]

Historian Frances Donaldson says, "If Belloc's feeling against the Jews was instinctive and under some control, Chesterton's was open and vicious, and he shared with Belloc the peculiarity that the Jews were never far from his thoughts."[44][46]

In a work of 1917, titled A Short History of England, Chesterton considers the royal decree of 1290 by which Edward I expelled Jews from England, a policy that remained in place until 1655. Chesterton writes that popular perception of Jewish moneylenders could well have led Edward I's subjects to regard him as a "tender father of his people" for "breaking the rule by which the rulers had hitherto fostered their bankers' wealth". He felt that Jews, "a sensitive and highly civilized people" who "were the capitalists of the age, the men with wealth banked ready for use", might legitimately complain that "Christian kings and nobles, and even Christian popes and bishops, used for Christian purposes (such as the Crusades and the cathedrals) the money that could only be accumulated in such mountains by a usury they inconsistently denounced as unchristian; and then, when worse times came, gave up the Jew to the fury of the poor".[47][48]

In The New Jerusalem, Chesterton made it clear that he believed that there was a "Jewish Problem" in Europe, in the sense that he believed that Jewish culture (though not Jewish ethnicity) separated itself from the nationalities of Europe.[49] He argued that he was quite in favour of a Jew becoming Prime Minister or Lord Chancellor, under the condition, though, that "every Jew must be dressed like an Arab [...] The point applies to any Jew, and to our own recovery of healthier relations with him. The point is that we should know where we are; and he would know where he is, which is in a foreign land." He suggested the formation of a Jewish homeland as a solution, and was later invited to Palestine by Jewish Zionists who saw him as an ally in their cause. Later he grew out of the notion of Palestine as a Jewish homeland, and suggested somewhere in Africa instead.

Chesterton, like Belloc, openly expressed his abhorrence of Hitler's rule almost as soon as it started.[50]

In The Truth about the Tribes Chesterton blasted German race theories writing "the essence of Nazi Nationalism is to preserve the purity of a race in a continent where all races are impure."[51]

The historian Simon Mayers points out that Chesterton wrote in works such as The Crank, The Heresy of Race, and The Barbarian as Bore against the concept of racial superiority and critiqued pseudo-scientific race theories saying they were akin to a new religion.[43] In The Truth About the Tribes Chesterton wrote "The curse of race religion is that it makes each separate man the sacred image which he worships. His own bones are the sacred relics; his own blood is the blood of St. Januarius."[43]

Mayers records that despite "his hostility towards Nazi antisemitism... [it's unfortunate that he made] claims that 'Hitlerism' was a form of Judaism, and that the Jews were partly responsible for race theory."[43] In The Judaism of Hitler Chesterton wrote "Hitlerism is almost entirely of Jewish origin."[43] In A Queer Choice Chesterton maintained that the only possible source of "the Hitlerites" idea of "a Chosen Race" was "from the Jews."[43] In The Crank Chesterton went on to say "If there is one outstanding quality in Hitlerism it is its Hebraism" and "the new Nordic Man has all the worst faults of the worst Jews: jealousy, greed, the mania of conspiracy, and above all, the belief in a Chosen Race."[43]

Mayers also shows that Chesterton didn't just portray Jews as culturally and religiously distinct, but racially as well. Chesterton wrote The Feud of the Foreigner in 1920 saying that the Jew "is a foreigner far more remote from us than is a Bavarian from a Frenchman; he is divided by the same type of division as that between us and a Chinaman or a Hindoo. He not only is not, but never was, of the same race."[43]

In The Everlasting Man, while writing about human sacrifice, Chesterton suggested that medieval stories about Jews killing children might have resulted from a distortion of genuine cases of devil-worship. Chesterton wrote "The Hebrew prophets were perpetually protesting against the Hebrew race relapsing into an idolatry that involved such a war upon children; and it is probable enough that this abominable apostasy from the God of Israel has occasionally appeared in Israel since, in the form of what is called ritual murder; not of course by any representative of the religion of Judaism, but by individual and irresponsible diabolists who did happen to be Jews."[43][52] Chesterton goes on in the paragraph to speak of "the enormous [devotional] popularity of the Child Martyr of the Middle Ages" and of little St. Hugh (figures held to have been ritual victims of Jews).[52]

The American Chesterton Society has devoted a whole issue of its magazine, Gilbert, to defending Chesterton against charges of antisemitism.[53]

Opposition to Eugenics

In Eugenics and Other Evils Chesterton attacked eugenics as Britain was moving towards passage of the Mental Deficiency Act 1913. Some backing the ideas of eugenics called for the government to sterilise people deemed "mentally defective;" this view did not gain popularity but the idea of segregating them from the rest of society and thereby preventing them from reproducing did gain traction. These ideas disgusted Chesterton who wrote "It is not only openly said, it is eagerly urged that the aim of the measure is to prevent any person whom these propagandists do not happen to think intelligent from having any wife or children."[54] He blasted the proposed wording for such measures as being so vague as to apply to anyone, including "Every tramp who is sulk, every labourer who is shy, every rustic who is eccentric, can quite easily be brought under such conditions as were designed for homicidal maniacs. That is the situation; and that is the point... we are already under the Eugenist State; and nothing remains to us but rebellion."[54]

He derided such ideas as founded on nonsense "as if one had a right to dragoon and enslave one's fellow citizens as a kind of chemical experiment".[54]

Chesterton also mocked the idea that poverty was a result of bad breeding "[it is a] strange new disposition to regard the poor as a race; as if they were a colony of Japs or Chinese coolies... The poor are not a race or even a type. It is senseless to talk about breeding them; for they are not a breed. They are, in cold fact, what Dickens describes: 'a dustbin of individual accidents,' of damaged dignity, and often of damaged gentility."[54]

"Chesterbelloc"

- See also G. K.'s Weekly.

Chesterton is often associated with his close friend, the poet and essayist Hilaire Belloc.[55][56] George Bernard Shaw coined the name "Chesterbelloc"[57] for their partnership,[58] and this stuck. Though they were very different men, they shared many beliefs;[59] Chesterton eventually joined Belloc in the Catholic faith, and both voiced criticisms of capitalism and socialism.[60] They instead espoused a third way: distributism.[61] G. K.'s Weekly, which occupied much of Chesterton's energy in the last 15 years of his life, was the successor to Belloc's New Witness, taken over from Cecil Chesterton, Gilbert's brother, who died in World War I.

Legacy

Literary

- Chesterton's The Everlasting Man contributed to C. S. Lewis's conversion to Christianity. In a letter to Sheldon Vanauken (14 December 1950)[62] Lewis calls the book "the best popular apologetic I know",[63] and to Rhonda Bodle he wrote (31 December 1947)[64] "the [very] best popular defence of the full Christian position I know is GK Chesterton's The Everlasting Man". The book was also cited in a list of 10 books that "most shaped his vocational attitude and philosophy of life".[65]

- Chesterton was a very early and outspoken critic of eugenics. Eugenics and Other Evils represents one of the first book length oppositions to the Eugenics movement that began to gain momentum in England during the early 1900s.[66]

- Chesterton's 1906 biography of Charles Dickens was largely responsible for creating a popular revival for Dickens's work as well as a serious reconsideration of Dickens by scholars.[67]

- Chesterton's novel The Man Who Was Thursday inspired the Irish Republican leader Michael Collins with the idea: "If you didn't seem to be hiding nobody hunted you out."[68] Collins's favourite work of Chesterton was The Napoleon of Notting Hill, and he was "almost fanatically attached to it", according to his friend Sir William Darling who cemented their friendship in their mutual appreciation of Chesterton's work.[69]

- Etienne Gilson praised Chesterton's Aquinas volume as follows: "I consider it as being, without possible comparison, the best book ever written on Saint Thomas... the few readers who have spent twenty or thirty years in studying St. Thomas Aquinas, and who, perhaps, have themselves published two or three volumes on the subject, cannot fail to perceive that the so-called 'wit' of Chesterton has put their scholarship to shame."[70]

- Chesterton's column in the Illustrated London News on 18 September 1909 had a profound effect on Mahatma Gandhi.[71] P. N. Furbank asserts that Gandhi was "thunderstruck" when he read it,[72] while Martin Green notes that "Gandhi was so delighted with this that he told Indian Opinion to reprint it."[73]

- Archbishop Fulton J. Sheen, author of seventy books, identified Chesterton as the stylist who had the greatest impact on his own writing, stating in his autobiography Treasure in Clay "The greatest influence in writing was G. K. Chesterton who never used a useless word, who saw the value of a paradox, and avoided what was trite."[74] Chesterton wrote the introduction for Sheen's book God and Intelligence in Modern Philosophy; A Critical Study in the Light of the Philosophy of Saint Thomas.[75]

- Canadian media theorist Marshall McLuhan was heavily influenced by Chesterton; McLuhan said the book What's Wrong with the World changed his life in terms of ideas and religion.[76]

- Neil Gaiman has stated that he grew up reading Chesterton in his school's library, and that The Napoleon of Notting Hill was an important influence on his own book Neverwhere, which used a quote from it as an epigraph. Gaiman also based the character Gilbert, from the comic book The Sandman, on Chesterton,[77] and the novel he co-wrote with Terry Pratchett is dedicated to him.

- Argentine author and essayist Jorge Luis Borges cited Chesterton as a major influence on his own fiction. In an interview with Richard Burgin during the late 1960s, Borges said, "Chesterton knew how to make the most of a detective story."[78]

- Chesterton's fence is the principle that reforms should not be made until the reasoning behind the existing state of affairs is understood. The quotation is from Chesterton’s 1929 book The Thing: Why I am a Catholic, in the chapter entitled "The Drift from Domesticity": "In the matter of reforming things, as distinct from deforming them, there is one plain and simple principle; a principle which will probably be called a paradox. There exists in such a case a certain institution or law; let us say, for the sake of simplicity, a fence or gate erected across a road. The more modern type of reformer goes gaily up to it and says, “I don’t see the use of this; let us clear it away." To which the more intelligent type of reformer will do well to answer: "If you don’t see the use of it, I certainly won’t let you clear it away. Go away and think. Then, when you can come back and tell me that you do see the use of it, I may allow you to destroy it."[79]

Other

In 1974, Father Ian Boyd, C.S.B, founded The Chesterton Review, a scholarly journal devoted to Chesterton and his circle. The journal is published by the G.K. Chesterton Institute for Faith and Culture based in Seton Hall University, South Orange, New Jersey, US

- Dale Ahlquist founded the American Chesterton Society in 1996 to explore and promote his writings.[80]

- In 2008, a Catholic high school, Chesterton Academy, opened in the Minneapolis area.

- In 2012, a crater on the planet Mercury was named Chesterton after the author.[81]

- In the Fall of 2014, a Catholic high school, G.K. Chesterton Academy of Chicago, opened in Highland Park, Illinois, a suburb of Chicago.[82]

- A fictionalised GK Chesterton is the central character in the Young Chesterton Chronicles, a series of young adult adventure novels written by John McNichol, and published by Sophia Institute Press and Bezalel Books.

- A fictionalised GK Chesterton is the central character in the G K Chesterton Mystery series, a series of detective novels written by Australian Kel Richards, and published by Riveroak Publishing.[83]

- Chesterton wrote the hymn O God of Earth and Altar which was printed in The Commonwealth and then included in the English Hymnal in 1906.[84] Several lines of the hymn are sung in the beginning of the song Revelations by the British heavy metal band Iron Maiden on their 1983 album Piece of Mind.[85] Lead singer Bruce Dickinson in an interview stated "I have a fondness for hymns. I love some of the ritual, the beautiful words, Jerusalem and there was another one, with words by G.K. Chesterton O God of Earth and Altar – very fire and brimstone: 'Bow down and hear our cry'. I used that for an Iron Maiden song, Revelations. In my strange and clumsy way I was trying to say look it's all the same stuff."[86]

Major works

| Library resources about G. K. Chesterton |

| By G. K. Chesterton |

|---|

- Chesterton, Gilbert Keith (1904), Ward, M, ed., The Napoleon of Notting Hill, UK: DMU.

- ——— (1905), Heretics, Project Gutenberg, ISBN 978-0-7661-7476-4.

- ——— (1906), Charles Dickens: A Critical Study.

- ——— (1908a), The Man Who Was Thursday.

- ——— (1908b), Orthodoxy.

- ——— (6 July 2008) [1911a], The Innocence of Father Brown, Project Gutenberg's.

- ——— (1911b), Ward, M, ed., The Ballad of the White Horse, UK: DMU.

- ——— (1912), Manalive.

- ———, Father Brown (short stories) (detective fiction).

- ——— (1920), Ward, M, ed., The New Jerusalem, UK: DMU.

- ——— (1922), Eugenics and Other Evils.

- ——— (1923), Saint Francis of Assisi.

- ——— (1925), The Everlasting Man.

- ——— (1933), Saint Thomas Aquinas.

- ——— (1936), The Autobiography.

- ——— (1950), Ward, M, ed., The Common Man, UK: DMU.

Articles

|

|

|

Short stories

- "The Crime of the Communist," Collier's Weekly, July 1934.

- "The Three Horsemen," Collier's Weekly, April 1935.

- "The Ring of the Lovers," Collier's Weekly, April 1935.

- "A Tall Story," Collier's Weekly, April 1935.

- "The Angry Street – A Bad Dream," Famous Fantastic Mysteries, February 1947.

Miscellany

- Elsie M. Lang, Literary London, with an introduction by G. K. Chesterton. London: T. Werner Laurie, 1906.

- George Haw, From Workhouse to Westminster, with an introduction by G.K. Chesterton. London: Cassell & Company, 1907.

- Darrell Figgs, A Vision of Life with an introduction by G.K. Chesterton. London: John Lane, The Bodley Head, 1909.

- C. Creighton Mandell, Hilaire Belloc: The Man and his Work, with an introduction by G. K. Chesterton. London: Methuen & Co., 1916.

- Harendranath Maitra, Hinduism: The World-Ideal, with an introduction by G. K. Chesterton. London: Cecil Palmer & Hayward, 1916.

- Maxim Gorki, Creatures that Once Were Men, with an introduction by G. K. Chesterton. New York: The Modern Library, 1918.

- Sibyl Bristowe, Provocations, with an introduction by G.K. Chesterton. London: Erskine Macdonald, 1918.

- W.J. Lockington, The Soul of Ireland, with an introduction by G.K. Chesterton. New York: The Macmillan Company, 1920.

- Arthur J. Penty, Post-Industrialism, with a preface by G. K. Chesterton. New York: The Macmillan Company, 1922.

- Leonard Merrick, The House of Lynch, with an introduction by G.K. Chesterton. London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1923.

- Henri Massis, Defence of the West, with a preface by G. K. Chesterton. London: Harcourt, Brace & Co., 1928.

- Francis Thompson, The Hound of Heaven and other Poems, with an introduction by G.K. Chesterton. Boston: International Pocket Library, 1936.

Notes

- ↑ Ian Ker, The Catholic Revival in English Literature (1845–1961): Newman, Hopkins, Belloc, Chesterton, Greene, Waugh (University of Notre Dame Press, 2003).

- ↑ "Obituary", Variety, 17 June 1936

- ↑ Douglas, J. D. (24 May 1974). "G.K. Chesterton, the Eccentric Prince of Paradox". Christianity Today. Retrieved 8 July 2014.

- 1 2 3 "Orthodoxologist", Time, 11 October 1943, retrieved 24 October 2008.

- 1 2 O'Connor, John. Father Brown on Chesterton, Frederick Muller Ltd., 1937.

- ↑ Douglas 1974: "Like his friend Ronald Knox he was both entertainer and Christian apologist. The world never fails to appreciate the combination when it is well done; even evangelicals sometimes give the impression of bestowing a waiver on deviations if a man is enough of a genius."

- ↑ "The Blunders of Our Parties", Illustrated London News, 19 April 1924.

- ↑ Ker, Ian (2011). G. K, Chesterton: A Biography. Oxford University Press, p. 485.

- ↑ John Simkin. "G. K. Chesterton". Spartacus Educational.

- ↑ Haushalter, Walter M. (1912). "Gilbert Keith Chesterton," The University Magazine, Vol. XI, p. 236.

- ↑ Ker (2011), p. 1.

- ↑ Ker (2011), p. 13.

- ↑ Chesterton 1936, Chapter IV.

- ↑ "GK Chesterton's Conversion Story", Socrates 58 (World Wide Web log), Google, March 2007.

- ↑ Chesterton, G. K. (1911). "The Flying Stars." In: The Innocence of Father Brown. London: Cassell & Company, Ltd., p. 118.

- ↑ Do We agree? A Debate between G. K. Chesterton and Bernard Shaw, with Hilaire Belloc in the Chair. London: C. Palmer, 1928.

- ↑ "Clarence Darrow debate". American Chesterton Society. Retrieved 21 May 2014.

- ↑ "G.K. Chesterton January, 1915". Clarence Darrow digital collection. University of Minnesota Law School. Retrieved 21 May 2014.

- ↑ Autobiography. London: Hutchinson & Co., Ltd., 1936, pp. 231–235.

- ↑ Wilson, A. N. (1984). Hilaire Belloc. London: Hamish Hamilton, p. 219.

- ↑ Cornelius, Judson K. Literary Humour. Mumbai: St Paul's Books. p. 144. ISBN 81-7108-374-9.

- ↑ Wodehouse, P.G. (1972), The World of Mr. Mulliner, Barrie and Jenkins, p. 172.

- ↑ Ward 1944, chapter XV.

- ↑ Biggs, Victoria (2005), "I", Caged in Chaos, Jessica Kingsley.

- ↑ Ker (2011).

- ↑ "G.K. Chesterton - CatholicAuthors.com". catholicauthors.com.

- ↑ Lauer, Quentin (1991). G.K. Chesterton: Philosopher Without Portfolio. New York City, NY: Fordham University Press, p. 25.

- ↑ Barker, Dudley (1973). G. K. Chesterton: A Biography. New York: Stein and Day, p. 287.

- ↑ "Gilbert Keith Chesterton (1874–1936)", Catholic authors.

- ↑ Antonio, Gaspari (14 July 2009). ""Blessed" G. K. Chesterton?: Interview on Possible Beatification of English Author". Zenit: The World Seen From Rome. Rome: Innovative Media. Retrieved 18 October 2010.

- ↑ "G. K. Chesterton". satucket.com.

- ↑ Bridges, Horace J. (1914). "G. K. Chesterton as Theologian." In: Ethical Addresses. Philadelphia: The American Ethical Union, pp. 21–44.

- ↑ Caldecott, Stratford (1999). "Was G.K. Chesterton a Theologian?," The Chesterton Review. (Rep. by CERC: Catholic Education Research Center.)

- ↑ Douglas, J. D. "G.K. Chesterton, the Eccentric Prince of Paradox," Christianity Today, 8 January 2001.

- ↑ Gray, Robert. "Paradox Was His Doxy," The American Conservative, 23 March 2009.

- ↑ Chesterton 1905, chapter 7.

- ↑ Chesterton 1905, chapter 4.

- ↑ Chesterton 1905, chapter 20.

- ↑ Chesterton 1908b, chapter 3.

- ↑ "The Suicide of Thought>". dmu.ac.uk.

- ↑ "Last orders", The Guardian, 9 April 2005.

- ↑ Chesterton, Gilbert. G.K. Chesterton to the Editor. The Nation, 18 March 1911.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Simon Mayers (2013). Chesterton's Jews: Stereotypes and Caricatures in the Literature and Journalism of G.K. Chesterton. pp. 85–87.

- 1 2 Frances Donaldson (2011). The Marconi Scandal. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 51.

- ↑ Todd M. Endelman (2002). The Jews of Britain, 1656 to 2000. p. 9.

- ↑ Dean Rapp, "The Jewish response to GK Chesterton's antisemitism, 1911–33." Patterns of Prejudice 24#2-4, (1990): 75-86. online

- ↑ Julius, Anthony (2010), Trials of the Diaspora: A History of Anti-Semitism in England, Oxford University Press, p. 422.

- ↑ Chesterton, G. K. (1917), A Short History of England, Chatto and Windus, pp. 108–109

- ↑ Chesterton 1920, Chapter 12.

- ↑ Pearce, Joseph (2005). Literary Giants, Literary Catholics. San Francisco: Ignatius Press. p. 95. ISBN 1-58617-077-5.

- ↑ The Collected Works of G.K. Chesterton, Volume 5, Ignatius Press, 1987, page 593

- 1 2 G. K. Chesterton (2007). The Everlasting Man. Mineola, NY: Dover publications. p. 117.

- ↑ "Was G.K. Chesterton Anti-Semitic?," by Dale Ahlquist.

- 1 2 3 4 Gilbert Keith Chesterton (1922). Eugenics and Other Evils. London, UK: Cassell and Company, Ltd.

- ↑ Mccarthy, John P. (1982). "The Historical Vision of Chesterbelloc," Modern Age, Vol. XXVI, No. 2, pp. 175–182.

- ↑ McInerny, Ralph. "Chesterbelloc," Catholic Dossier, May/June 1998.

- ↑ Shaw, George Bernard (1918). "Belloc and Chesterton," The New Age, Vol. II, No. 16, pp. 309–311.

- ↑ Lynd, Robert (1919). "Mr. G. K. Chesterton and Mr. Hilaire Belloc." In: Old and New Masters. London: T. Fisher Unwin Ltd., pp. 25–41.

- ↑ McInerny, Ralph. "The Chesterbelloc Thing", The Catholic Thing, 30 September 2008.

- ↑ Wells, H. G. (1908). "About Chesterton and Belloc," The New Age, Vol. II, No. 11, pp. 209–210 (Rep. in Social Forces in England and America, 1914).

- ↑ "Belloc and the Distributists," The American Review, November 1933.

- ↑ Lewis, Clive Staples, A Severe Mercy.

- ↑ Letter to Sheldon Vanauken, 14 December 1950.

- ↑ Lewis, Clive Staples, The Collected Letters, 2, p. 823.

- ↑ The Christian Century, 6 June 1962.

- ↑ "The Enemy of Eugenics", by Russell Sparkes.

- ↑ Ahlquist 2006, p. 286.

- ↑ Forester, Margery (2006). Michael Collins – The Lost Leader, Gill & MacMillan, p. 35.

- ↑ James Mackay (1996). Michael Collins: A Life. London, England: Mainstream Publishing. p. Chapter 2.

- ↑ Gilson, Etienne (1987), "Letter to Chesterton's editor", in Pieper, Josef, Guide to Thomas Aquinas, University of Notre Dame Press, pp. 6–7.

- ↑ Rajmohan Gandhi (2007). Gandhi: The Man, His People, and the Empire. Los Angeles: University of California Press. pp. 139–141.

- ↑ Furbank, PN (1974), "Chesterton the Edwardian", in Sullivan, John, GK Chesterton: A Centenary Appraisal, Harper and Row.

- ↑ Green, Martin B (2009), Gandhi: Voice of a New Age Revolution, Axios, p. 266.

- ↑ Sheen, Fulton J. (2008). Treasure in Clay. New York: Image Books/Doubleday, p. 79.

- ↑ Fulton J. Sheen. God and Intelligence. IVE Press.

- ↑ Marchand, Philip (1998). Marshall McLuhan: The Medium and the Messenger: A Biography. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, pp. 28–30.

- ↑ Bender, Hy (2000). The Sandman Companion : A Dreamer's Guide to the Award-Winning Comic Series DC Comics, ISBN 1-56389-644-3.

- ↑ Burgin, Richard (1969). Conversations with Jorge Luis Borges. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, p. 35.

- ↑ Chesterton, G. K. (1929). "The Drift from Domesticity." In: The Thing. London: Sheed & Ward, p. 35.

- ↑ "The American Chesterton Society". American Chesterton Society.

- ↑ "Chesterton", Gazetteer of Planetary Nomenclature, United States: Geological Survey, 17 September 2012.

- ↑ School built around G.K. Chesterton to open in Highland Park, United States Chicago: highlandpark suntimes, 19 March 2014.

- ↑ http://www.amazon.com/Murder-Mummys-Chesterton-Mystery-Series/dp/1589199634

- ↑ Erik Routley (2005). An English-speaking Hymnal Guide. GIA publications. p. 129.

- ↑ Jacqueline Edmondson, ed. (2013). Music in American Life: An Encyclopedia of the Songs, Styles, Stars, and Stories That Shaped Our Culture. Santa Barbara, CA: Greenwood. p. 39.

- ↑ Bruce Dickinson: Faith And Music (1999).

Further reading

- Ahlquist, Dale (2012), The Complete Thinker: The Marvelous Mind of G.K. Chesterton, Ignatius Press, ISBN 978-1-58617-675-4.

- ——— (2003), G.K. Chesterton: Apostle of Common Sense, Ignatius Press, ISBN 978-0-89870-857-8.

- Belmonte, Kevin (2011). Defiant Joy: The Remarkable Life and Impact of G.K. Chesterton. Nashville, Tenn.: Thomas Nelson.

- Blackstock, Alan R. (2012). The Rhetoric of Redemption: Chesterton, Ethical Criticism, and the Common Man. New York. Peter Lang Publishing.

- Braybrooke, Patrick (1922). Gilbert Keith Chesterton. London: Chelsea Publishing Company.

- Cammaerts, Émile (1937). The Laughing Prophet: The Seven Virtues And G. K. Chesterton. London: Methuen & Co., Ltd.

- Campbell, W. E. (1908). "G.K. Chesterton: Inquisitor and Democrat," The Catholic World, Vol. LXXXVIII, pp. 769–782.

- Campbell, W. E. (1909). "G.K. Chesterton: Catholic Apologist" The Catholic World, Vol. LXXXIX, No. 529, pp. 1–12.

- Chesterton, Cecil (1908). G.K. Chesterton: A Criticism. London: Alston Rivers (Rep. by John Lane Company, 1909).

- Clipper, Lawrence J. (1974). G.K. Chesterton. New York: Twayne Publishers.

- Coates, John (1984). Chesterton and the Edwardian Cultural Crisis. Hull University Press.

- Coates, John (2002). G.K. Chesterton as Controversialist, Essayist, Novelist, and Critic. N.Y.: E. Mellen Press

- Conlon, D. J. (1987). G.K. Chesterton: A Half Century of Views. Oxford University Press.

- Cooney, A (1999), G.K. Chesterton, One Sword at Least, London: Third Way, ISBN 0-9535077-1-8.

- Coren, Michael (2001) [1989], Gilbert: The Man who was G.K. Chesterton, Vancouver: Regent College Publishing, ISBN 9781573831956, OCLC 45190713.

- Corrin, Jay P. (1981). G.K. Chesterton & Hilaire Belloc: The Battle Against Modernity. Ohio University Press.

- Ervine, St. John G. (1922). "G.K. Chesterton." In: Some Impressions of my Elders. New York: The Macmillan Company, pp. 90–112.

- Ffinch, Michael (1986), G.K. Chesterton, Harper & Row.

- Hitchens, Christopher (2012). "The Reactionary," The Atlantic.

- Herts, B. Russell (1914). "Gilbert K. Chesterton: Defender of the Discarded." In: Depreciations. New York: Albert & Charles Boni, pp. 65–86.

- Hollis, Christopher (1970). The Mind of Chesterton. London: Hollis & Carter.

- Hunter, Lynette (1979). G.K. Chesterton: Explorations in Allegory. London: Macmillan Press.

- Jaki, Stanley (1986). Chesterton: A Seer of Science. University of Illinois Press.

- Jaki, Stanley (1986). "Chesterton's Landmark Year." In: Chance or Reality and Other Essays. University Press of America.

- Kenner, Hugh (1947). Paradox in Chesterton. New York: Sheed & Ward.

- Kimball, Roger (2011). "G. K. Chesterton: Master of Rejuvenation," The New Criterion, Vol. XXX, p. 26.

- Kirk, Russell (1971). "Chesterton, Madmen, and Madhouses," Modern Age, Vol. XV, No. 1, pp. 6–16.

- Knight, Mark (2004). Chesterton and Evil. Fordham University Press.

- Lea, F.A. (1947). "G. K. Chesterton." In: Donald Attwater (ed.) Modern Christian Revolutionaries. New York: Devin-Adair Co.

- McCleary, Joseph R. (2009). The Historical Imagination of G.K. Chesterton: Locality, Patriotism, and Nationalism. Taylor & Francis.

- McLuhan, Marshall (1936), "GK Chesterton: A Practical Mystic", Dalhousie Review, 15 (4).

- McNichol, J. (2008), The Young Chesterton Chronicles, Book One: The Tripods Attack!, Manchester, NH: Sophia Institute, ISBN 978-1-933184-26-5.

- Oddie, William (2010). Chesterton and the Romance of Orthodoxy: The Making of GKC, 1874–1908. Oxford University Press.

- Orage, Alfred Richard. (1922). "G.K. Chesterton on Rome and Germany." In: Readers and Writers (1917–1921). London: George Allen & Unwin, pp. 155–161.

- Oser, Lee (2007). The Return of Christian Humanism: Chesterton, Eliot, Tolkien, and the Romance of History. University of Missouri Press.

- Paine, Randall (1999), The Universe and Mr. Chesterton, Sherwood Sugden, ISBN 0-89385-511-1.

- Pearce, Joseph (1997), Wisdom and Innocence – A Life of GK Chesterton, Ignatius Press, ISBN 978-0-89870-700-7.

- Peck, William George (1920). "Mr. G.K. Chesterton and the Return to Sanity." In: From Chaos to Catholicism. London: George Allen & Unwin, pp. 52–92.

- Raymond, E. T. (1919). "Mr. G.K. Chesterton." In: All & Sundry. London: T. Fisher Unwin, pp. 68–76.

- Schall, James V. (2000). Schall on Chesterton: Timely Essays on Timeless Paradoxes. Catholic University of America Press.

- Scott, William T. (1912). Chesterton and Other Essays. Cincinnati: Jennings & Graham.

- Seaber, Luke (2011). G.K. Chesterton's Literary Influence on George Orwell: A Surprising Irony. New York: Edwin Mellen Press.

- Sheed, Wilfrid (1971). "Chesterbelloc and the Jews," The New York Review of Books, Vol. XVII, No. 3.

- Shuster, Norman (1922). "The Adventures of a Journalist: G.K. Chesterton." In: The Catholic Spirit in Modern English Literature. New York: The Macmillan Company, pp. 229–248.

- Slosson, Edwin E. (1917). "G.K. Chesterton: Knight Errant of Orthodoxy." In: Six Major Prophets. Boston: Little, Brown and Company, pp. 129–189.

- Smith, Marion Couthouy (1921). "The Rightness of G.K. Chesterton," The Catholic World, Vol. CXIII, No. 678, pp. 163–168.

- Stapleton, Julia (2009). Christianity, Patriotism, and Nationhood: The England of G.K. Chesterton. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books.

- Sullivan, John (1974), G.K. Chesterton: A Centenary Appraisal, London: Paul Elek, ISBN 0-236-17628-5.

- Tonquédec, Joseph de (1920). G.K. Chesterton, ses Idées et son Caractère, Nouvelle Librairie National.

- Ward, Maisie (1944), Gilbert Keith Chesterton, Sheed & Ward.

- Ward, Maisie (1952). Return to Chesterton, London: Sheed & Ward.

- West, Julius (1915). G.K. Chesterton: A Critical Study. London: Martin Secker.

- Williams, Donald T (2006), Mere Humanity: G.K. Chesterton, CS Lewis, and JRR Tolkien on the Human Condition.

External links

| Wikilivres has original media or text related to this article: |

- G. K. Chesterton at DMOZ

- Works by G. K. Chesterton at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about G. K. Chesterton at Internet Archive

- Works by G. K. Chesterton at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Works by G.K. Chesterton, at HathiTrust

- "Archival material relating to G. K. Chesterton". UK National Archives.

- The American Chesterton Society, retrieved 28 October 2010.

- G. K. Chesterton: Quotidiana

- G.K. Chesterton research collection at The Marion E. Wade Center at Wheaton College

- G.K. Chesterton Archival Collection at the University of St. Michael's College at the University of Toronto