Kinetic isotope effect

An example of the kinetic isotope effect. In the reaction of methyl bromide with cyanide, the kinetic isotope effect of the carbon in the methyl group was found to be 1.082 ± 0.008.[1][2] |

The kinetic isotope effect (KIE) is the change in the rate of a chemical reaction when one of the atoms in the reactants is substituted with one of its isotopes. Formally, it is the ratio of rate constants for the reactions involving the light (kL) and the heavy (kH) isotopically substituted reactants:

Background

The kinetic isotope effect is considered to be one of the most essential and sensitive tools for the study of reaction mechanisms, the knowledge of which allows the improvement of the desirable qualities of the corresponding reactions. For example, kinetic isotope effects can be used to reveal whether a nucleophilic substitution reaction follows a unimolecular (SN1) or bimolecular (SN2) pathway.

In the reaction of methyl bromide and cyanide (shown in the introduction), the observed methyl carbon kinetic isotope effect indicates an SN2 mechanism.[1] Depending on the pathway, different strategies may be used to stabilize the transition state of the rate-determining step of the reaction and improve the reaction rate and selectivity, which are important for industrial applications.

_(2).png)

Isotopic rate changes are most pronounced when the relative mass change is greatest, since the effect is related to vibrational frequencies of the affected bonds. For instance, changing a hydrogen atom (H) to its isotope deuterium (D) represents a 100% increase in mass, whereas in replacing carbon-12 with carbon-13, the mass increases by only 8 percent. The rate of a reaction involving a C–H bond is typically 6–10 times faster than the corresponding C–D bond, whereas a 12C reaction is only 4 percent faster than the corresponding 13C reaction (even though, in both cases, the isotope is one atomic mass unit heavier).

Isotopic substitution can modify the rate of reaction in a variety of ways. In many cases, the rate difference can be rationalized by noting that the mass of an atom affects the vibrational frequency of the chemical bond that it forms, even if the electron configuration is nearly identical. Heavier isotopes will (classically) lead to lower vibration frequencies, or, viewed quantum mechanically, will have lower zero-point energy. With a lower zero-point energy, more energy must be supplied to break the bond, resulting in a higher activation energy for bond cleavage, which in turn lowers the measured rate (see, for example, the Arrhenius equation).

Classification

Primary kinetic isotope effects

A primary kinetic isotope effect may be found when a bond to the isotopically labeled atom is being formed or broken. For the previously mentioned nucleophilic substitution reactions, primary kinetic isotope effects have been investigated for both the leaving groups, the nucleophiles, and the α-carbon at which the substitution occurs. Interpretation of the leaving group kinetic isotope effects had been difficult at first due to significant contributions from temperature independent factors. Kinetic isotope effects at the α-carbon can be used to develop some understanding into the symmetry of the transition state in SN2 reactions, although this kinetic isotope effect is less sensitive than what would be ideal, also due to contribution from non-vibrational factors.[1]

Secondary kinetic isotope effects

A secondary kinetic isotope effect is observed when no bond to the isotopically substituted atom in the reactant is broken or formed in the rate-determining step of a reaction. By its definition, secondary kinetic isotope effects tend to be much smaller than primary kinetic isotope effects; however, since kinetic isotope effects can be calculated and measured to very high precision, secondary kinetic isotope effects are still very useful for elucidating reaction mechanisms.

For the aforementioned nucleophilic substitution reactions, secondary hydrogen kinetic isotope effects at the α-carbon provide a direct means to distinguish between SN1 and SN2 reactions. It has been found that SN1 reactions typically lead to large secondary kinetic isotope effects, approaching to their theoretical maximum at about 1.22, while SN2 reactions typically yield kinetic isotope effects that are very close to or less than unity. Kinetic isotope effects that are greater than 1 are referred to as normal kinetic isotope effects, while kinetic isotope effects that are less than one are referred to as inverse kinetic isotope effects. In general, smaller force constants in the transition state are expected to yield a normal kinetic isotope effect, and larger force constants in the transition state are expected to yield an inverse kinetic isotope effect when stretching vibrational contributions dominate the kinetic isotope effect.[1]

The magnitudes of such secondary isotope effects at the α-carbon are largely determined by the Cα-H(D) vibrations. For an SN1 reaction, since the carbon is converted into an sp2 hybridized carbenium ion during the transition state for the rate-determining step with an increase in Cα-H(D) bond order, an inverse kinetic isotope effect would be expected if only the stretching vibrations were important. The observed large normal kinetic isotope effects are found to be caused by significant out-of-plane bending vibrational contributions when going from the reactants to the transition state of carbenium formation. For SN2 reactions, bending vibrations still play an important role for the kinetic isotope effect, but stretching vibrational contributions are of more comparable magnitude, and the resulting kinetic isotope effect may be normal or inverse depending on the specific contributions of the respective vibrations.[1][3][4]

Theory

The theoretical treatment of isotope effects relies heavily on transition state theory, which assumes a single potential energy surface for the reaction, and a barrier between the reactants and the products on this surface, on top of which resides the transition state.[5][6] The kinetic isotope effect arises largely from the changes which the isotopic perturbation produces along the minimum energy pathway on this reaction energy surface, which may only be accounted for with quantum mechanical treatments of the system. Depending on the mass and energy of the reacting species, quantum mechanical tunneling may also make a large contribution to an observed kinetic isotope effect.[5]

Of the various theoretical treatments of kinetic isotope effects, Bigeleisen's seems to be the most popular. His basic general equation for the hydrogen/deuterium kinetic isotope effects is given below, neglecting tunnelling contributions which can be introduced as a separate factor. The subscripts H and D refer to hydrogen and deuterium substituted substrates, respectively.[4]

The S factors are the symmetry numbers for the reactants and transition states. The M factors are the molecular masses of the corresponding species, and the I factors are the moments of inertia about the three principal axes. The ui factors are determined from the corresponding vibrational frequencies, νi, through ui = h νi/kT. N and N‡ are the number of atoms in the reactants and the transition states, respectively.[4] The complicated expression given above can be represented as the product of four separate factors, as shown below, from which some possible simplifications for hydrogen/deuterium kinetic isotope effects can be more easily seen.[4]

The S factor is the ratio of the symmetry numbers for the various species. These symmetry numbers do not lead to isotopic fractionation, so the S factor can be set to be 1.000. The MMI factor refers to the ratio of the molecular masses and the moments of inertia. Since hydrogen and deuterium tend to be much lighter compared to most reactants and transition states, the MMI factor is usually also approximated as unity. The EXC factor corrects for the kinetic isotope effect caused by the reactions of vibrationally excited molecules. The contribution of this factor is also negligible when the reactions are carried out at or near room temperature. Hence, for hydrogen/deuterium kinetic isotope effects, the observed values are typically governed by the zero-point energy contributions, which can be represented as follows:[4]

If the zero-point energy difference between the stretching vibrations of a carbon-hydrogen and carbon-deuterium bond is allowed to disappear in the transition state, the expression given above predicts a maximum for kH/kD as 6.9. If the weakening of two bending vibrations are also taken into account, kH/kD values as large as 15-20 can be predicted. Bending frequencies are very unlikely to vanish in the transition state, however, and quite few kH/kD values exceed 7-8 near room temperature. Furthermore, it is often found that tunneling is a major factor when they do exceed such values. Hence, more often than not, weakening of bending frequencies is not an important cause of large kinetic isotope effects.

For isotope effects involving elements other than hydrogen, most of these simplifications are not valid, and may depend largely on some of the neglected factors. In many cases and especially for hydrogen-transfer reactions, contributions to kinetic isotope effects from tunneling are significant (see below).

As mentioned, especially for hydrogen/deuterium substitution, most kinetic isotope effects arise from the difference in zero-point energy (ZPE) between the reactants and the transition state of the isotopologues in question, and this difference can be understood qualitatively with the following description: within the Born–Oppenheimer approximation, the potential energy curve is the same for both isotopic species. However, a quantum-mechanical treatment of the energy introduces discrete vibrational levels onto this curve, and the lowest possible energy state of a molecule corresponds to the lowest vibrational energy level, which is slightly higher in energy than the minimum of the potential energy curve. This difference, referred to as the zero-point energy, is a manifestation of the Heisenberg uncertainty principle that necessitates an uncertainty in the C-H or C-D bond length. Since the heavier (in this case the deuterated) species behaves more "classically," its vibrational energy levels are closer to the classical potential energy curve, and it has a lower zero-point energy. The zero-point energy differences between the two isotopic species, at least in most cases, diminish in the transition state, since the bond force constant decreases during bond breaking. Hence, the lower zero-point energy of the deuterated species translates into a larger activation energy for its reaction, as shown in the following figure,leading to a normal kinetic isotope effect.[7]

The following simple expressions relating deuterium and tritium kinetic isotope effects, which are also known as the Swain equation (or the Swain-Schaad-Stivers equations), can be derived from the general expression given above using some simplifications:[5][8]

i.e.,

In deriving these expressions, symmetry terms are omitted. The subscript "s" refers to these "semiclassical" kinetic isotope effects, which disregard quantum tunneling. Tunneling contributions must be treated separately as a correction factor.

Tunneling

In some cases, an additional rate enhancement is seen for the lighter isotope, possibly due to quantum mechanical tunnelling. This is typically only observed for reactions involving bonds to hydrogen atoms. Tunneling occurs when a molecule penetrates through a potential energy barrier rather than over it.[9][10] Although not allowed by the laws of classical mechanics, particles can pass through classically forbidden regions of space in quantum mechanics based on wave–particle duality.[11]

Analysis of tunneling can be made using Bell's modification of the Arrhenius equation, which includes the addition of a tunneling factor, Q:

where A is the Arrhenius parameter, E is the barrier height and

where and

Examination of the β term shows exponential dependency on the mass of the particle. As a result, tunneling is much more likely for a lighter particle such as hydrogen. Simply doubling the mass of a tunneling proton by replacing it with its deuterium isotope drastically reduces the rate of such reactions. As a result, very large kinetic isotope effects are observed that can not be accounted for by differences in zero point energies.

In addition, the β term depends linearly with barrier width, 2a. As with mass, tunneling is greatest for small barrier widths. Optimal tunneling distances of protons between donor and acceptor atom is 0.4 Å.[13]

Tunneling is a quantum mechanical effect tied to the laws of wave mechanics, not kinetics. Therefore, tunneling tends to become more important at low temperatures, where even the smallest kinetic energy barriers may not be overcome but can be tunneled through.[9]

Peter S. Zuev et al. reported rate constants for the ring expansion of 1-methylcyclobutylfluorocarbene to be 4.0 x 10−6/s in nitrogen and 4.0 x 10−5/s in argon at 8 kelvin. They calculated that at 8 kelvin, the reaction would proceed via a single quantum state of the reactant so that the reported rate constant is temperature independent and the tunneling contribution to the rate was 152 orders of magnitude greater than the contribution of passage over the transition state energy barrier.[14]

So despite the fact that conventional chemical reactions tend to slow down dramatically as the temperature is lowered, tunneling reactions rarely change at all. Particles that tunnel through an activation barrier are a direct result of the fact that the wave function of an intermediate species, reactant or product is not confined to the energy well of a particular trough along the energy surface of a reaction but can "leak out" into the next energy minimum. In light of this, tunneling should be temperature independent.[9][15]

For the hydrogen abstraction from gaseous n-alkanes and cycloalkanes by hydrogen atoms over the temperature range 363–463 K, the H/D kinetic isotope effect data were characterized by small preexponential factor ratios AH/AD ranging from 0.43 to 0.54 and large activation energy differences from 9.0 to 9.7 kJ/mol. Basing their arguments on transition state theory, the small A factor ratios associated with the large activation energy differences (usually about 4.5 kJ/mol for C–H(D) bonds) provided strong evidence for tunneling. For the purpose of this discussion, it is important is that the A factor ratio for the various paraffins they used was approximately constant throughout the temperature range.[16]

The observation that tunneling is not entirely temperature independent can be explained by the fact that not all molecules of a certain species occupy their vibrational ground state at varying temperatures. Adding thermal energy to a potential energy well could cause higher vibrational levels other than the ground state to become populated. For a conventional kinetically driven reaction, this excitation would only have a small influence on the rate. However, for a tunneling reaction, the difference between the zero point energy and the first vibrational energy level could be huge. The tunneling correction term Q is linearly dependent on barrier width and this width is significantly diminished as the number vibrational modes on the Morse potential increase. The decrease of the barrier width can have such a huge impact on the tunneling rate that even a small population of excited vibrational states would dominate this process.[9][15]To determine if tunneling is involved in KIE of a reaction with H or D, a few criteria are considered:

1.Δ(EaH-EaD) > Δ(ZPEH-ZPED) (Ea=activation energy; ZPE=zero point energy)

2.Reaction still proceeds at lower temperatures.

3.The Arrhenius pre-exponential factors AD/AH is not equal to 1.

4.A large negative entropy of activation.

5.The geometries of the reactants and products are usually very similar.[9]

Also for reactions where isotopes include H, D and T, a criterion of tunneling is the Swain-Schaad relations which compare the rate constants (k) of the reactions where H,D or T are exchanged:

kH/kT=(kD/kT)X and kH/kT=(kH/kD)Y

In organic reactions, this proton tunneling effect has been observed in such reactions as the deprotonation and iodination of nitropropane with hindered pyridine base[17] with a reported KIE of 25 at 25 °C:

and in a 1,5-sigmatropic hydrogen shift[18] although it is observed that it is difficult to extrapolate experimental values obtained at elevated temperatures to lower temperatures:[19][20]

It has long been speculated that high efficiency of enzyme catalysis in proton or hydride ion transfer reactions could be due partly to the quantum mechanical tunneling effect. Environment at the active site of an enzyme positions the donor and acceptor atom close to the optimal tunneling distance, where the amino acid side chains can "force" the donor and acceptor atom closer together by electrostatic and noncovalent interactions. It is also possible that the enzyme and its unusual hydrophobic environment inside a reaction site provides tunneling-promoting vibration.[21] Studies on ketosteroid isomerase have provided experimental evidence that the enzyme actually enhances the coupled motion/hydrogen tunneling by comparing primary and secondary kinetic isotope effects of the reaction under enzyme catalyzed and non-enzyme catalyzed conditions.[22]

Many examples exist for proton tunneling in enzyme catalyzed reactions that were discovered by KIE. A well studied example is methylamine dehydrogenase, where large primary KIEs of 5–55 have been observed for the proton transfer step.[23]

Another example of tunneling contribution to proton transfer in enzymatic reactions is the reaction carried out by alcohol dehydrogenase. Competitive KIEs for the hydrogen transfer step at 25 °C resulted in 3.6 and 10.2 for primary and secondary KIEs, respectively.[24]

Transient kinetic isotope effect

Isotopic effect expressed with the equations given above only refer to reactions that can be described with first-order kinetics. In all instances in which this is not possible, transient kinetic isotope effects should be taken into account using the GEBIK and GEBIF equations.[25]

Kinetic isotope effect experiments

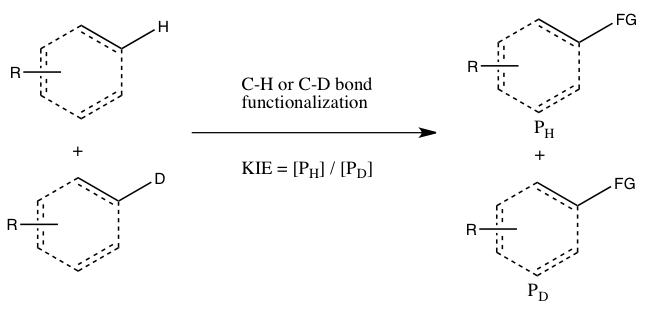

Simmons and Hartwig refer to the following three cases as the main types of kinetic isotope effect experiments involving C-H bond functionalization:[26]

- A) KIE determined from absolute rates of two parallel reactions

In this experiment, the rate constants for the normal substrate and its isotopically labeled analogue are determined independently, and the KIE is obtained as a ratio of the two. The accuracy of the measured KIE is severely limited by the accuracy with which each of these rate constants can be measured. Furthermore, reproducing the exact conditions in the two parallel reactions can be very challenging. Nevertheless, this measurement of the kinetic isotope effect is the only one that may tell that C-H bond cleavage occurs in the rate-determining step without a doubt.

- B) KIE determined from an intermolecular competition

In this type of experiment, the same substrates that are used in Experiment A are employed, but they are allowed in to react in the same container, instead of two separate containers. The kinetic isotope effect from this experiment is determined by the relative amount of products formed from C-H versus C-D functionalization (or it can be inferred from the relative amounts of unreacted starting materials). It is necessary to quench the reaction before it goes to completion to observe the kinetic isotope effect (see the Evaluation section below). This experiment type ensures that both C-H and C-D bond functionalizations occur under exactly the same conditions, and the ratio of products from C-H and C-D bond functionalizations can be measured with much greater precision than the rate constants in Experiment A. Moreover, only a single measurement of product concentrations from a single sample is required. However, an observed kinetic isotope effect from this experiment is more difficult to interpret, since it may either mean that C-H bond cleavage occurs during the rate-determining step or at a product-determining step ensuing the rate-determining step. The absence of a kinetic isotope effect, at least according to Simmons and Hartwig, is nonetheless indicative of the C-H bond cleavage not occurring during the rate-determining step.

- C) KIE determined from an intramolecular competition

This type of experiment is analogous to Experiment B, except this time there is an intramolecular competition for the C-H or C-D bond functionalization. In most cases, the substrate possesses a directing group (DG) between the C-H and C-D bonds. Calculation of the kinetic isotope effect from this experiment and its interpretation follow the same considerations as that of Experiment B.

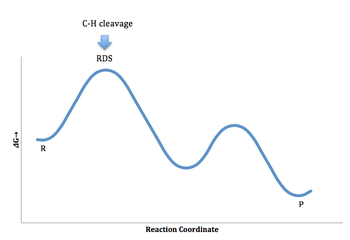

Apart from the differences in feasibility and precision between the different kinds of experiments, they may also differ in terms of the information they may provide. For example, if a reaction follows the following energy profile, all three experiments will yield a significant primary kinetic isotope effect:

On the other hand, if a reaction follows the following energy profile, in which the C-H or C-D bond cleavage is irreversible but occurs after the rate-determining step (RDS), no significant kinetic isotope effect will be observed with Experiment A, since the overall rate is not affected by the isotopic substitution. Nevertheless, the irreversible C-H bond cleavage step will give a primary kinetic isotope effect with the other two experiments, since the second step would still affect the product distribution. Therefore, with Experiments B and C, it is possible to observe the kinetic isotope effect even if C-H or C-D bond cleavage occurs not in the rate-determining step, but in the product-determining step.

A large part of the kinetic isotope effect arises from vibrational zero-point energy differences between the reactant ground state and the transition state that vary between the reactant and its isotopically substituted analogue. While it is possible to carry involved calculations of kinetic isotope effects using computational chemistry, much of the work done is of simpler order that involves the investigation of whether particular isotopic substitutions produce a detectable kinetic isotope effect or not. Vibrational changes from isotopic substitution at atoms away from the site where the reaction occurs tend to cancel between the reactant and the transition state. Therefore, the presence of a kinetic isotope effect indicates that the isotopically labeled atom is at or very near the reaction site.

The absence of an isotope effect is more difficult to interpret: It may mean that the isotopically labeled atom is away from the reaction site, but it may also mean that there are certain compensating effects that lead to the lack of an observable kinetic isotope effect. For example, the differences between the reactant and the transition state zero-point energies may be identical between the normal reactant and its isotopically labeled version. Alternatively, it may mean that the isotopic substitution is at the reaction site, but vibrational changes associated with bonds to this atom occur after the rate-determining step. Such a case is illustrated in the following example, in which ABCD represents the atomic skeleton of a molecule.

Assuming steady state conditions for the intermediate ABC, the overall rate of reaction is the following:

If the first step is rate-determining, this equation reduces to:

Or if the second step is rate-determining, the equation reduces to:

In most cases, isotopic substitution at A, especially if it is a heavy atom, will not alter k1 or k2, but it will most probably alter k3. Hence, if the first step is rate-determining, there will not be an observable kinetic isotope effect in the overall reaction with isotopic labeling of A, but there will be one if the second step is rate-determining. For intermediate cases where both steps have comparable rates, the magnitude of the kinetic isotope effect will depend on the ratio of k3 and k2.

Isotopic substitution of D will alter k1 and k2 while not affecting k3. The kinetic isotope effect will always be observable with this substitution since k1 appears in the simplified rate expression regardless of which step is rate-determining, but it will be less pronounced if the second step is rate-determining due to some cancellation between the isotope effects on k1 and k2. This outcome is related to the fact that equilibrium isotope effects are usually smaller than kinetic isotope effects.

Isotopic substitution of B will clearly alter k3, but it may also alter k1 to a lesser extent if the B-C bond vibrations are affected in the transition state of the first step. There may thus be a small isotope effect even if the first step is rate-determining.

This hypothetical consideration reveals how observing kinetic isotope effects may be used to investigate reaction mechanisms. The existence of a kinetic isotope effect is indicative of a change to the vibrational force constant of a bond associated with the isotopically labeled atom at or before the rate-controlling step. Intricate calculations may be used to learn a great amount of detail about the transition state from observed kinetic isotope effects. More commonly, though, the mere qualitative knowledge that a bond associated with the isotopically labeled atom is altered in a certain way can be very useful.[27]Evaluation of rate constant ratios from intermolecular competition reactions

In competition reactions, the kinetic isotope effect is calculated from isotopic product or remaining reactant ratios after the reaction, but these ratios depend strongly on the extent of completion of the reaction. Most commonly, the isotopic substrate will consist of molecules labeled in a specific position and their unlabeled, ordinary counterparts.[5] It is also possible in case of 13C kinetic isotope effects, as well as similar cases, to simply rely on the natural abundance of the isotopic carbon for the kinetic isotope effect experiments, eliminating the need for isotopic labeling.[28] The two isotopic substrates will react through the same mechanism, but at different rates. The ratio between the amounts of the two species in the reactants and the products will thus change gradually over the course of the reaction, and this gradual change can be treated in the following manner:[5] Assume that two isotopic molecules, A1 and A2, undergo irreversible competition reactions in the following manner:

The kinetic isotope effect for this scenario is found to be:

Where F1 and F2 refer to the fraction of conversions for the isotopic species A1 and A2, respectively.

In this treatment, all other reactants are assumed to be non-isotopic. Assuming further that the reaction is of first order with respect to the isotopic substrate A, the following general rate expression for both these reactions can be written:

Since f([B],[C],…) does not depend on the isotopic composition of A, it can be solved for in both rate expressions with A1 and A2, and the two can be equated to derive the following relations:

Where [A1]0 and [A2]0 are the initial concentrations of A1 and A2, respectively. This leads to the following kinetic isotope effect expression:

Which can also be expressed in terms of fraction amounts of conversion of the two reactions, F1 and F2, where 1-Fn=[An]/[An]0 for n = 1 or 2, as follows:

As for obtaining the kinetic isotope effects, mixtures of substrates containing stable isotopes may be analyzed using a mass spectrometer, which yields the ratios of the isotopic molecules in the initial substrate (defined here as [A2]0/[A1]0=R0), in the substrate after some conversion ([A2]/[A1]=R), or in the product ([P2]/[P1]=RP). When one of the species, e.g. 2, is a radioactive isotope, its mixture with the other species can also be analyzed by its radioactivity, which is measured in molar activities that are proportional to [A2]0 / ([A1]0+[A2]0) ≈ [A2]0/[A1]0 = R0 in the initial substrate, [A2] / ([A1]+[A2]) ≈ [A2]/[A1] = R in the substrate after some conversion, and [R2] / ([R1]+[R2]) ≈ [R2]/[R1] = RP, so that the same ratios as in the other case can be measured as long as the radioactive isotope is present in tracer amounts. Such ratios may also be determined using NMR spectroscopy.[29][30]

When the substrate composition is followed, the following kinetic isotope effect expression in terms of R0 and R can be derived:

Taking the ratio of R and R0 using the previously derived expression for F2, one gets:

Isotopic enrichment of the starting material can be calculated from the dependence of R/R0 on F1 for various kinetic isotope effects, yielding the following figure. Because of the exponential dependence, even very low kinetic isotope effects lead to large changes in isotopic composition of the starting material at high conversions.

When the products are followed, the kinetic isotope effect can be calculated using the products ratio RP along with R0 as follows:

Case studies

Primary hydrogen isotope effects

Primary hydrogen kinetic isotope effects refer to cases in which a bond to the isotopically labeled hydrogen is formed or broken in the rate-determining step of the reaction. These are the most commonly measured kinetic isotope effects, and much of the previously covered theory refers to primary kinetic isotope effects. When there is adequate evidence that transfer of the labeled hydrogen occurs in the rate-determining step of a reaction, if a fairly large kinetic isotope effect is observed, e.g. kH/kD of at least 5-6 or kH/kT about 10-13 at room temperature, it is quite likely that the hydrogen transfer is linear and that the hydrogen is fairly symmetrically located in the transition state. It is usually not possible to make comments about tunneling contributions to the observed isotope effect unless the effect is very large. If the primary kinetic isotope effect is not as large, it is generally considered to be indicative of a significant contribution from heavy-atom motion to the reaction coordinate, although it may also mean that hydrogen transfer follows a nonlinear pathway.[5]

Secondary hydrogen isotope effects

The secondary hydrogen isotope effects or secondary kinetic isotope effect (SKIE) arises in cases where the isotopic substitution is remote from the bond being broken. The remote atom, nonetheless, influences the internal vibrations of the system that via changes in the zero point energy (ZPE) affect the rates of chemical reactions.[31] Such effects are expressed as ratios of rate for the light isotope to that of the heavy isotope and can be "normal" (ratio is greater than or equal to 1) or "inverse" (ratio is less than 1) effects.[32] SKIE are defined as α,β (etc.) secondary isotope effects where such prefixes refer to the position of the isotopic substitution relative to the reaction center (see alpha and beta carbon).[33] The prefix α refers to the isotope associated with the reaction center while the prefix β refers to the isotope associated with an atom neighboring the reaction center and so on.

In physical organic chemistry, SKIE is discussed in terms of electronic effects such as induction, bond hybridization, or hyperconjugation.[34] These properties are determined by electron distribution, and depend upon vibrationally averaged bond length and angles that are not greatly affected by isotopic substitution. Thus, the use of the term "electronic isotope effect" while legitimate is discouraged from use as it can be misinterpreted to suggest that the isotope effect is electronic in nature rather than vibrational.[33]

SKIE's can be explained in terms of changes in orbital hybridization. When the hybridization of a carbon atom changes from sp3 to sp2, a number of vibrational modes (stretches, in-plane and out-of-plane bending) are affected. The in-plane and out-of-plane bending in an sp3 hybridized carbon are similar in frequency due to the symmetry of an sp3 hybridized carbon. In an sp2 hybridized carbon the in-plane bend is much stiffer than the out-of-plane bending resulting in a large difference in the frequency, the ZPE and thus the SKIE (which exists when there is a difference in the ZPE of the reactant and transition state).[9] The theoretical maximum change caused by the bending frequency difference has been calculated as 1.4.[9]

When carbon undergoes a reaction that changes its hybridization from sp3 to sp2, the out of plane bending force constant at the transition state is weaker as it is developing sp2 character and a "normal" SKIE is observed with typical values of 1.1 to 1.2.[9] Conversely, when carbon's hybridization changes from sp2 to sp3, the out of plane bending force constants at the transition state increase and an inverse SKIE is observed with typical values of 0.8 to 0.9.[9]

More generally the SKIE for reversible reactions can be "normal" one way and "inverse" the other if bonding in the transition state is midway in stiffness between substrate and product, or they can be "normal" both ways if bonding is weaker in the transition state, or "inverse" both ways if bonding is stronger in the transition state than in either reactant.[32]

An example of an "inverse" α secondary kinetic isotope effect can be seen in the work of Fitzpatrick and Kurtz who used such an effect to distinguish between two proposed pathways for the reaction of d-amino acid oxidase with nitroalkane anions.[35] Path A involved a nucleophilic attack on the coenzyme FAD, while path B involves a free-radical intermediate. As path A results in the intermediate carbon changing hybridization from sp2 to sp3 an "inverse" a SKIE is expected. If path B occurs then no SKIE should be observed as the free radical intermediate does not change hybridization. An SKIE of 0.84 was observed and Path A verified as shown in the scheme below.

Another example of a SKIE is the oxidation of benzyl alcohols by dimethyldioxirane where three transition states for different mechanisms were proposed. Again, by considering how and if the hydrogen atoms were involved in each, researchers predicted whether or not they would expect an effect of isotopic substitution of them. Then, analysis of the experimental data for the reaction allowed them to choose which pathway was most likely based on the observed isotope effect.[36]

Secondary hydrogen isotope effects from the methylene hydrogens were also used to show that Cope rearrangement in 1,5-hexadiene follow a concerted bond rearrangement pathway, and not one of the alternatively proposed allyl radical or 1,4-diyl pathways, all of which are presented in the following scheme.[37]

Alternative mechanisms for the Cope rearrangement of 1,5-hexadiene: (from top to bottom), allyl radical, synchronous concerted, and 1,4-dyil pathways. The predominant pathway is found to be the middle one, which has six delocalized π electrons corresponding to an aromatic intermediate.[37]

Steric isotope effects

|

| |

The steric isotope effect is a SKIE that does not involve bond breaking or formation. This effect is attributed to the different vibrational amplitudes of isotopologues.[38] An example of such an effect is the racemization of 9,10-dihydro-4,5-dimethylphenanthrene.[39] The smaller amplitude of vibration for deuterium as compared to hydrogen in C–H (carbon–hydrogen), C–D (carbon–deuterium) bonds results in a smaller van der Waals radius or effective size in addition to a difference in the ZPE between the two. When there is a greater effective bulk of molecules containing one over the other this may be manifested by a steric effect on the rate constant. For the example above deuterium racemizes faster than the hydrogen isotopologue resulting in a steric isotope effect.

Another example of the steric isotope effect is in the deslipping reaction of rotaxanes. The deuterium isotope, due to its smaller effective size, allows easier passage of the stoppers through the macrocycle, resulting in faster rates of deslipping for the deuterated rotaxanes.[40]

Inverse kinetic isotope effects

Reactions are known where the deuterated species reacts faster than the undeuterated analogue, and these cases are said to exhibit inverse kinetic isotope effects (IKIE). IKIE's are often observed in the reductive elimination of alkyl metal hydrides, e.g. (Me2NCH2CH2NMe2)PtMe(H). In such cases the C-D bond in the transition state, an agostic species, is highly stabilized relative to the C–H bond.

Solvent hydrogen kinetic isotope effects

For the solvent isotope effects to be measurable, a finite fraction of the solvent must have a different isotopic composition than the rest. Therefore, large amounts of the less common isotopic species must be available, limiting observable solvent isotope effects to isotopic substitutions involving hydrogen. Detectable kinetic isotope effects occur only when solutes exchange hydrogen with the solvent or when there is a specific solute-solvent interaction near the reaction site. Both such phenomena are common for protic solvents, in which the hydrogen is exchangeable, and they may form dipole-dipole interactions or hydrogen bonds with polar molecules.[5]

Carbon-13 isotope effects

Most organic reactions involve the breaking and making of bonds to a carbon; thus, it is reasonable to expect detectable carbon isotope effects. When 13C is used as the label, the change in mass of the isotope is only ~8%, though, which limits the observable kinetic isotope effects to much smaller values than the ones observable with hydrogen isotope effects.

Compensating for variations in 13C natural abundance

Often, the largest source of error in a study that depends on the natural abundance of carbon is the slight variation in natural 13C abundance itself. Such variations arise because the starting materials used in the reaction are themselves products of some other reactions that have kinetic isotope effects and corresponding isotopic enrichments in the products. To compensate for this error when NMR spectroscopy is used to determine the kinetic isotope effect, the following guidelines have been proposed:[29][30]

- Choose a carbon that is remote from the reaction center that will serve as a reference and assume it does not have a kinetic isotope effect in the reaction.

- In the starting material that has not undergone any reaction, determine the ratios of the other carbon NMR peak integrals to that of the reference carbon.

- Obtain the same ratios for the carbons in a sample of the starting material after it has undergone some reaction.

- The ratios of the latter ratios to the former ratios yields R/R0.

If these as well as some other precautions listed by Jankowski are followed, kinetic isotope effects with precisions of three decimal places can be achieved.[29][30]

Isotope effects with elements heavier than carbon

Interpretation of carbon isotope effects are usually complicated by simultaneously forming and breaking bonds to carbon. Even reactions that involve only bond cleavage from the carbon, such as SN1 reactions, involve strengthening of the remaining bonds to carbon. In many such reactions, leaving group isotope effects tend to be easier to interpret. For example, substitution and elimination reactions in which chlorine act as a leaving group are convenient to interpret, especially since chlorine acts as a monatomic species with no internal bonding to complicate the reaction coordinate, and it has two stable isotopes, 35Cl and 37Cl, both with high abundance. The major challenge to the interpretation of such isotope affects is the solvation of the leaving group.[5]

Owing to experimental uncertainties, measurement of isotope effect may entail significant uncertainty. Often isotope effects are determined through complementary studies on a series of isotopomers. Accordingly, it is quite useful to combine hydrogen isotope effects with heavy-atom isotope effects. For instance, determining nitrogen isotope effect along with hydrogen isotope effect was used to show that the reaction of 2-phenylethyltrimethylammonium ion with ethoxide in ethanol at 40oC follows an E2 mechanism, as opposed to alternative non-concerted mechanisms. This conclusion was reached upon showing that this reaction yields a nitrogen isotope effect, k14/k15, of 1.0133±0.0002 along with a hydrogen kinetic isotope effect of 3.2 at the leaving hydrogen.[5]

Similarly, combining nitrogen and hydrogen isotope effects was used to show that syn eliminations of simple ammonium salts also follow a concerted mechanism, which was a question of debate before. In the following two reactions of 2-phenylcyclopentyltrimethylammonium ion with ethoxide, both of which yield 1-phenylcyclopentene, both isomers exhibited a nitrogen isotope effect k14/k15 at 60oC. Although the reaction of the trans isomer, which follows syn elimination, has a smaller nitrogen kinetic isotope effect (1.0064) compared to the cis isomer which undergoes anti elimination (1.0108), both results are large enough to be indicative of weakening of the C-N bond in the transition state that would occur in a concerted process.

Other Examples

Since kinetic isotope effects arise from differences in isotopic masses, the largest observable kinetic isotope effects are associated with isotopic substitutions of hydrogen with deuterium (100% increase in mass) or tritium (200% increase in mass). Kinetic isotope effects from isotopic mass ratios can be as large as 36.4 using muons. They have produced the lightest hydrogen atom, 0.11H (0.113 amu), in which an electron orbits around a positive muon (μ+) "nucleus" that has a mass of 206 electrons. They have also prepared the heaviest hydrogen atom analogue by replacing one electron in helium with a negative muon (μ−) to form Heμ with an atomic mass of 4.116 amu. Since the negative muon is much heavier than an electron, it orbits much closer to the nucleus, effectively shielding one proton, making Heμ to behave as 4.1H. With these exotic species, the reaction of H with 1H2 was investigated. Rate constants from reacting the lightest and the heaviest hydrogen analogues with 1H2 were then used to calculate the k0.11/k4.1 kinetic isotope effect, in which there is a 36.4 fold difference in isotopic masses. For this reaction, isotopic substitution happens to produce an inverse kinetic isotope effect, and the authors report a kinetic isotope effect as low as 1.74 x 10−4, which is the smallest kinetic isotope effect ever reported.[41]

The kinetic isotope effect leads to a specific distribution of deuterium isotopes in natural products, depending on the route they were synthesized in nature. By NMR spectroscopy, it is therefore easy to detect whether the alcohol in wine was fermented from glucose, or from illicitly added saccharose.

Another reaction mechanisms that was elucidated using the kinetic isotope effect is the halogenation of toluene:[42]

In this particular "intramolecular KIE" study, a benzylic hydrogen undergoes radical substitution by bromine using N-bromosuccinimide as the brominating agent. It was found that PhCH3 brominates 4.86x faster than PhCD3. A large KIE of 5.56 is associated with the reaction of ketones with bromine and sodium hydroxide.[43]

In this reaction the rate-limiting step is formation of the enolate by deprotonation of the ketone. In this study the KIE is calculated from the reaction rate constants for regular 2,4-dimethyl-3-pentanone and its deuterated isomer by optical density measurements.

See also

- Effect of temperature on KIE

- Reaction mechanism

- Transient kinetic isotope fractionation

- Magnetic isotope effect

- Crossover experiment

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Westaway, Kenneth C. (2006). "Using kinetic isotope effects to determine the structure of the transition states of SN2 reactions". Advances in Physical Organic Chemistry. 41: 217–273. doi:10.1016/S0065-3160(06)41004-2.

- ↑ Lynn, K. R.; Yankwich, Peter E. (5 August 1961). Journal of the American Chemical Society. 83 (15): 3220–3223. doi:10.1021/ja01476a012. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Poirier, Raymond A.; Wang, Youliang; Westaway, Kenneth C. (March 1994). "A Theoretical Study of the Relationship between Secondary .alpha.-Deuterium Kinetic Isotope Effects and the Structure of SN2 Transition States". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 116 (6): 2526–2533. doi:10.1021/ja00085a037.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Buncel, E.; Lee, C.C. Isotopes in Organic Chemistry. Elsevier: Amsterdam, 1977, Vol. 5.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Melander, L.; Saunders, W.H., Jr. Reaction Rates of Isotopic Molecules. Wiley: New York, 1980.

- ↑ Bigeleisen, J.; Wolfsberg, M. Adv. Chem. Phys. 1958, 1, 15.

- ↑ Carpenter, B.K. Nature Chem. 2010, 2, 80.

- ↑ Swain, C. Gardner; Stivers, Edward C.; Reuwer, Joseph F.; Schaad, Lawrence J. (1 November 1958). "Use of Hydrogen Isotope Effects to Identify the Attacking Nucleophile in the Enolization of Ketones Catalyzed by Acetic Acid". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 80 (21): 5885–5893. doi:10.1021/ja01554a077.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Anslyn, E. V.; Dougherty, D. A. (2006). Modern Physical Organic Chemistry. University Science Books. pp. 428–437. ISBN 1-891389-31-9.

- ↑ Razauy, M. (2003). Quantum Theory of Tunneling. World Scientific. ISBN 981-238-019-1.

- ↑ Silbey, R. J.; Alberty, R. A.; Bawendi, M. G. (2005). Physical Chemistry. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 326–338. ISBN 0-471-21504-X.

- ↑ Borgis, D.; Hynes, J. T. (1993). "Dynamical theory of proton tunneling transfer rates in solution: General formulation". Chemical Physics. 170 (3): 315–346. Bibcode:1993CP....170..315B. doi:10.1016/0301-0104(93)85117-Q.

- 1 2 Krishtalik, L. I. (2000). "The mechanism of the proton transfer: An outline". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 1458: 6–27. doi:10.1016/S0005-2728(00)00057-8.

- ↑ Zuev, P. S. (2003). "Carbon tunneling from a single quantum state". Science. 299 (5608): 867–70. Bibcode:2003Sci...299..867Z. doi:10.1126/science.1079294. PMID 12574623.

- 1 2 Atkins, P.; de Paula, J. (2006). Atkins' Physical Chemistry. Oxford University Press. pp. 286–288, 816–818. ISBN 978-0-19-870072-2.

- ↑ Fujisaki, N.; Ruf, A.; Gaeumann, T. (1987). "Tunnel effects in hydrogen-atom-transfer reactions as studied by the temperature dependence of the hydrogen deuterium kinetic isotope effects". Journal of Physical Chemistry. 91 (6): 1602. doi:10.1021/j100290a062.

- ↑ Lewis, E. S.; Funderburk, L. (1967). "Rates and isotope effects in the proton transfers from 2-nitropropane to pyridine bases". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 89 (10): 2322–2327. doi:10.1021/ja00986a013.

- ↑ Dewar, M. J. S.; Healy, E. F.; Ruiz, J. M. (1988). "Mechanism of the 1,5-sigmatropic hydrogen shift in 1,3-pentadiene". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 110 (8): 2666–2667. doi:10.1021/ja00216a060.

- ↑ von Eggers Doering, W.; Zhao, X. (2006). "Effect on Kinetics by Deuterium in the 1,5-Hydrogen Shift of a Cisoid-Locked 1,3(Z)-Pentadiene, 2-Methyl-10-methylenebicyclo[4.4.0]dec-1-ene: Evidence for Tunneling?". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 128 (28): 9080–9085. doi:10.1021/ja057377v. PMID 16834382.

- ↑ In this study the KIE is measured by sensitive proton NMR. The extrapolated KIE at 25 °C is 16.6 but the margin of error is high

- ↑ Kohen, A.; Klinman, J. P. (1999). "Hydrogen tunneling in biology". Chemistry & Biology. 6 (7): R191–198. doi:10.1016/S1074-5521(99)80058-1. PMID 10381408.

- ↑ Wilde, T. C.; Blotny, G.; Pollack, R. M. (2008). "Experimental evidence for enzyme-enhanced coupled motion/quantum mechanical hydrogen tunneling by ketosteroid isomerase". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 130 (20): 6577–6585. doi:10.1021/ja0732330. PMID 18426205.

- ↑ Truhlar, D. G.; Gao, J.; Alhambra, C.; Garcia-Viloca, M.; Corchado, J.; Sánchez, M.; Villà, J. (2002). "The Incorporation of Quantum Effects in Enzyme Kinetics Modeling". Accounts of Chemical Research. 35 (6): 341–349. doi:10.1021/ar0100226.

- ↑ Kohen, A.; Klinman, J. P. (1998). "Enzyme Catalysis: Beyond Classical Paradigms". Accounts of Chemical Research. 31 (7): 397–404. doi:10.1021/ar9701225.

- ↑ Maggi, F.; Riley, W. J. (2010). "Mathematical treatment of isotopologue and isotopomer speciation and fractionation in biochemical kinetics". Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta. 74 (6): 1823. Bibcode:2010GeCoA..74.1823M. doi:10.1016/j.gca.2009.12.021.

- ↑ Simmons, E.M.; Hartwig, J.F. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 3066-3072.

- ↑ Buncel, E.; Lee, C.C. Isotopes in Organic Chemistry. Elsevier: Amsterdam, 1977, Vol. 3.

- ↑ Singleton, Daniel A.; Thomas, Allen A. (September 1995). "High-Precision Simultaneous Determination of Multiple Small Kinetic Isotope Effects at Natural Abundance". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 117 (36): 9357–9358. doi:10.1021/ja00141a030.

- 1 2 3 Jankowski, S. Ann. Rep. NMR Spec. 2009, 68, 149.

- 1 2 3 Kwan, Eugene. "CHEM 106 Course Notes - Lecture 14 - Computational Chemistry" (PDF). Retrieved 2 November 2013.

- ↑ Hennig, C.; Oswald, R. B.; Schmatz, S. (2006). "Secondary Kinetic Isotope Effect in Nucleophilic Substitution: A Quantum-Mechanical Approach". Journal of Physical Chemistry A. 110 (9): 3071–3079. doi:10.1021/jp0540151.

- 1 2 Cleland, W. W. (2003). "The Use of Isotope Effects to Determine Enzyme Mechanisms". Journal of Biological Chemistry. 278 (52): 51975–51984. doi:10.1074/jbc.X300005200. PMID 14583616.

- 1 2 IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 2nd ed. (the "Gold Book") (1997). Online corrected version: (2006–) "Secondary isotope effect".

- ↑ "Definition of isotope effect, secondary". Chemistry Dictionary.

- ↑ Kurtz, K. A.; Fitzpatrick, P. F. (1997). "pH and Secondary Kinetic Isotope Effects on the Reaction of D-Amino Acid Oxidase with Nitroalkane Anions: Evidence for Direct Attack on the Flavin by Carbanions". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 119 (5): 1155–1156. doi:10.1021/ja962783n.

- ↑ Angelis, Y. S.; Hatzakis, N. S.; Smonou, I.; Orfanopoulos, M. (2006). "Oxidation of benzyl alcohols by dimethyldioxirane. The question of concerted versus stepwise mechanisms probed by kinetic isotope effects". Tetrahedron Letters. 42 (22): 3753–3756. doi:10.1016/S0040-4039(01)00539-1.

- 1 2 Houk, K.N.; Gustafson, S.M.; Black, K.A. JACS 1992, 114, 8565.

- ↑ IUPAC, Compendium of Chemical Terminology, 2nd ed. (the "Gold Book") (1997). Online corrected version: (2006–) "steric isotope effect".

- ↑ Mislow, K.; Graeve, R.; Gordon, A. J.; Wahl, G. H. (1963). "A Note on Steric Isotope Effects. Conformational Kinetic Isotope Effects in The Racemization of 9,10-Dihydro-4,5-Dimethylphenanthrene". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 85 (8): 1199–1200. doi:10.1021/ja00891a038.

- ↑ Felder, T.; Schalley, C. A. (2003). "Secondary Isotope Effects on the Deslipping Reaction of Rotaxanes: High-Precision Measurement of Steric Size". Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 42 (20): 2258–2260. doi:10.1002/anie.200350903. PMID 12772156.

- ↑ Fleming, D. G.; Arseneau, D. J.; Sukhorukov, O.; Brewer, J. H.; Mielke, S. L.; Schatz, G. C.; Garrett, B. C.; Peterson, K. A.; Truhlar, D. G. (27 January 2011). "Kinetic Isotope Effects for the Reactions of Muonic Helium and Muonium with H2". Science. 331 (6016): 448–450. doi:10.1126/science.1199421. PMID 21273484.

- ↑ Wiberg, K. B.; Slaugh, L. H. (1958). "The Deuterium Isotope Effect in the Side Chain Halogenation of Toluene". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 80 (12): 3033–3039. doi:10.1021/ja01545a034.

- ↑ Lynch, R. A.; Vincenti, S. P.; Lin, Y. T.; Smucker, L. D.; Subba Rao, S. C. (1972). "Anomalous kinetic hydrogen isotope effects on the rat of ionization of some dialkyl substituted ketones". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 94 (24): 8351–8356. doi:10.1021/ja00779a012.