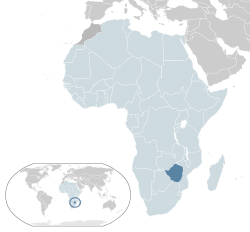

Hinduism in Zimbabwe

|

Part of a series on

|

Hinduism in Zimbabwe came with indentured servants brought by the colonial British administrators in late 19th and early 20th-century to what was then called British South Africa Company and later Rhodesia.[1] This Hindu migration was different from those in East African countries such as Kenya and Uganda where Hindus arrived voluntarily for jobs but without restrictive contracts; it was quite similar to the arrival of Indian workers in South Africa, Mauritius, Guyana, Trinidad and Tobago with slave-like contract restrictions for plantation work owned by Europeans, particularly the British.[1][2] Most Hindus who arrived for these indentured plantation work were originally from Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Gujarat, Maharashtra and Tamil Nadu, people escaping from major repetitive famines in colonial British India from 1860s to 1910s. These laborers came for a fixed period irrevocable contract of exclusive servitude, with an option to either go back to India with plantation paid return fare, or stay in a local settlement after the contract ended.[2] Most chose to stay and continue working for a salary.[1]

- Ancient and medieval history

Archaeological studies in Zimbabwe and the Swahili coast have revealed evidence that suggests that Indian traders had a small presence and sporadic interaction with the African people during the Roman Empire period (early 1st millennium CE) and thereafter, long pre-dating the European colonial era.[1][3][4] Similarly, genetic studies suggest a direct ancient African-Indian trade and cooperation because by the 1st millennium BCE African crops were adopted in India, and Indian crops as well as the domesticated zebu cow (Bos indicus) were adopted in Africa, but these were missing from north Africa, the northeastern horn of Africa and Arabia during that age.[5] The development of gold mining and processing methods among the Shona people in Zimbabwe highlands increased its trading activity with India before the 12th century, particularly through the city of Sofala.[6] However, these traders did not engage in religious missionary activity and Hinduism was limited to the traders.[6][7]

- Colonial era migration

Hinduism came with indentured laborers brought to Zimbabwe, and they were a part of a global movement of workers during the colonial era, to help with plantation and mining related projects when local skilled labor was unavailable, to build infrastructure projects, establish services, retail markets and for administrative support.[8][9][10] The immigrants, some educated and skilled but mostly poor and struggling in famine prone areas of India, came to escape starvation and work in plantations owned by the Europeans.[9]

According to Ezra Chitando, the 19th- and early 20th-century encounters between European Christians with both Hinduism and African Traditional Religions in Zimbabwe were complex, generally demonizing and dehumanizing both Hinduism and African religions, but the Christian missionaries never totally condemn Hinduism or African religions.[11] The Christian officials identified some positive elements in both, but states Chitando, then called upon the Hindu Indian workers and local Africans to "abandon their traditions and embrace their [Christian] version of reality".[11] In contrast to Christian missionary approach, neither Hinduism nor African Traditional Religions were missionary in their approach or goals.[11]

- Contemporary Hindu community

Hindus are a tiny minority in modern era Zimbabwe.[12] The "Hindu Religious and Cultural Institute" of Harare discusses Sanatana Dharma with children born into Hindu families of Zimbabwe, and welcomes non-Hindus. The major centers of Hindu community of about 3,000 in Harare include various schools, the Goanese Association, the Hindu Society, the Tamil Sangam, the Brahma Kumaris yoga centers and the Ramakrishna Vedanta Society all of which are in Harare.[13][14][15] The Krishna-oriented ISKCON has a centre at Marondera.

References

- 1 2 3 4 Constance Jones; James D. Ryan (2006). Encyclopedia of Hinduism. Infobase Publishing. pp. 10–11. ISBN 978-0-8160-7564-5.

- 1 2 "Forced Labour: A New System of Slavery?". The National Archives. Government of the United Kingdom. 2007. Retrieved 2016-10-17.

- ↑ Alexis Catsambis; Ben Ford; Donny L. Hamilton (2011). The Oxford Handbook of Maritime Archaeology. Oxford University Press. pp. 479–480, 514–523. ISBN 978-0-19-537517-6.

- ↑ Lionel Casson (1974), Rome's Trade with the East: The Sea Voyage to Africa and India, Transactions of the American Philological Association, The Johns Hopkins University Press, Vol. 110 (1980), pp. 21-36

- ↑ Edward A. Alpers (2014). The Indian Ocean in World History. Oxford University Press. pp. 24–26, 30–39. ISBN 978-0-19-533787-7.

- 1 2 Hromnik, Cyril A. (1991). "Dravidian Gold Mining and Trade in Ancient Komatiland". Journal of Asian and African Studies. 26 (3-4): 283–290. doi:10.1177/002190969102600309. Retrieved 2016-10-17.

- ↑ Craig A. Lockard (2014). Societies, Networks, and Transitions: A Global History. Cengage. pp. 273–274. ISBN 978-1-305-17707-9.

- ↑ Sushil Mittal; Gene Thursby (2009). Studying Hinduism: Key Concepts and Methods. Routledge. pp. 87–88. ISBN 978-1-134-41829-9.

- 1 2 Kim Knott (2016). Hinduism: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press. pp. 91–92. ISBN 978-0-19-874554-9.

- ↑ DAVID LEVINSON; KAREN CHRISTENSEN (2003). Encyclopedia of Community: From the Village to the Virtual World. Sage Publications. p. 592. ISBN 978-0-7619-2598-9.

- 1 2 3 Klaus Koschorke; Jens Holger Schjørring (2005). African Identities and World Christianity in the Twentieth Century. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. pp. 185–187. ISBN 978-3-447-05331-0.

- ↑ Religious groups in Zimbabwe, IRF 2006

- ↑ The Hindoo Society Newsletter, Harare, Zimbabwe; Current Archives

- ↑ Modern Temple Rises Out of Zimbabwe Soil, Hinduism Today (1991)

- ↑ The Hindoo Society, Harare, Zimbabwe, Official Website

Further reading

- Steven Vertovec (2013). The Hindu Diaspora: Comparative Patterns. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-136-36712-0.

- Richard Carver (1990). Where Silence Rules: The Suppression of Dissent in Malawi. Human Rights Watch. ISBN 978-0-929692-73-9.

External links

- Harare Hindu Society

- Hindus in Zimbabwe

- Hindu Associations in Zimbabwe

- Brahma Kumaris Centres in Zimbabwe