Gothic fiction

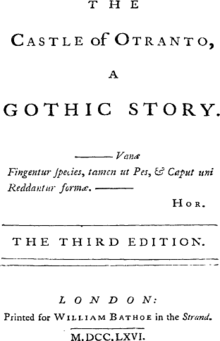

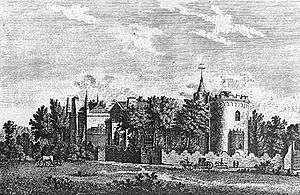

Gothic fiction, which is largely known by the subgenre of Gothic horror, is a genre or mode of literature and film that combines fiction and horror, death, and at times romance. Its origin is attributed to English author Horace Walpole, with his 1764 novel The Castle of Otranto, subtitled (in its second edition) "A Gothic Story." The effect of Gothic fiction feeds on a pleasing sort of terror, an extension of Romantic literary pleasures that were relatively new at the time of Walpole's novel. It originated in England in the second half of the 18th century and had much success in the 19th, as witnessed by Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein and the works of Edgar Allan Poe. Another well known novel in this genre, dating from the late Victorian era, is Bram Stoker’s Dracula. The name Gothic refers to the (pseudo)-medieval buildings, emulating Gothic architecture, in which many of these stories take place. This extreme form of romanticism was very popular in England and Germany. The English Gothic novel also led to new novel types such as the German Schauerroman and the French Georgia.

Early Gothic romances

The novel usually regarded as the "first Gothic novel" is Horace Walpole's The Castle of Otranto, first published in 1764. Horace Walpole's declared aim was to combine elements of the medieval romance, which he deemed too fanciful, and the modern novel, which he considered to be too confined to strict realism.[1] The basic plot created many other staple Gothic generic traits, including a threatening mystery and an ancestral curse, as well as countless trappings such as hidden passages and oft-fainting heroines. Walpole published the first edition disguised as a medieval romance from Italy discovered and republished by a fictitious translator. When Walpole admitted to his authorship in the second edition, its originally favourable reception by literary reviewers changed into rejection. The reviewers' rejection reflected a larger cultural bias: the romance was usually held in contempt by the educated as a tawdry and debased kind of writing; the genre had gained some respectability only through the works of Samuel Richardson and Henry Fielding.[2] A romance with superstitious elements, and moreover void of didactical intention, was considered a setback and not acceptable. Walpole's forgery, together with the blend of history and fiction, contravened the principles of the Enlightenment and associated the Gothic novel with fake documentation.

Clara Reeve

Clara Reeve, best known for her work The Old English Baron (1778), set out to take Walpole's plot and adapt it to the demands of the time by balancing fantastic elements with 18th-century realism. The question now arose whether supernatural events that were not as evidently absurd as Walpole's would not lead the simpler minds to believe them possible.[3]

Ann Radcliffe

Ann Radcliffe developed the technique of the explained supernatural in which every seemingly supernatural intrusion is eventually traced back to natural causes.[4] Her success attracted many imitators.[5] Among other elements, Ann Radcliffe introduced the brooding figure of the Gothic villain (A Sicilian Romance in 1790), a literary device that would come to be defined as the Byronic hero. Radcliffe's novels, above all The Mysteries of Udolpho (1794), were best-sellers. However, along with most novels at the time, they were looked down upon by many well-educated people as sensationalist nonsense.

Radcliffe also provided an aesthetic for the genre in an influential article "On the Supernatural in Poetry",[6] examining the distinction and correlation between horror and terror in Gothic fiction.[7]

Developments in continental Europe and The Monk

Romantic literary movements developed in continental Europe concurrent with the development of the Gothic novel. The roman noir ("black novel") appeared in France, by such writers as François Guillaume Ducray-Duminil, Baculard d'Arnaud and Madame de Genlis. In Germany, the Schauerroman ("shudder novel") gained traction with writers as Friedrich Schiller, with novels like The Ghost-Seer (1789), and Christian Heinrich Spiess, with novels like Das Petermännchen (1791/92). These works were often more horrific and violent than the English Gothic novel.

Matthew Gregory Lewis's lurid tale of monastic debauchery, black magic and diabolism entitled The Monk (1796) offered the first continental novel to follow the conventions of the Gothic novel. Though Lewis's novel could be read as a pastiche of the emerging genre, self-parody that had been a constituent part of the Gothic from the time of the genre's inception with Walpole's Otranto. Lewis's portrayal of depraved monks, sadistic inquisitors and spectral nuns, and by his scurrilous view of the Catholic Church, appalled some readers, but The Monk was important in the genre's development.

The Monk also influenced Ann Radcliffe in her last novel, The Italian (1797). In this book, the hapless protagonists are ensnared in a web of deceit by a malignant monk called Schedoni and eventually dragged before the tribunals of the Inquisition in Rome, leading one contemporary to remark that if Radcliffe wished to transcend the horror of these scenes, she would have to visit hell itself.[8]

The Marquis de Sade used a subgothic framework for some of his fiction, notably The Misfortunes of Virtue and Eugenie de Franval, though the Marquis himself never thought of his like this. Sade critiqued the genre in the preface of his Reflections on the novel (1800) stating that the Gothic is "the inevitable product of the revolutionary shock with which the whole of Europe resounded". Contemporary critics of the genre also noted the correlation between the French revolutionary Terror and the "terrorist school" of writing represented by Radcliffe and Lewis.[9] Sade considered The Monk to be superior to the work of Ann Radcliffe.

Germany

German gothic fiction is usually described by the term Schauerroman ("shudder novel"). However, genres of Gespensterroman/Geisterroman ("ghost novel"), Räuberroman ("robber novel"), and Ritterroman ("chivalry novel") also frequently share plot and motifs with the British "gothic novel". As its name suggests, the Räuberroman focuses on the life and deeds of outlaws, influenced by Friedrich von Schiller's drama The Robbers (1781). Heinrich Zschokke's Abällino, der grosse Bandit (1793) was translated into English by M.G. Lewis as The Bravo of Venice in 1804. The Ritterroman focuses on the life and deeds of the knights and soldiers, but features many elements found in the gothic novel, such as magic, secret tribunals, and medieval setting. Benedikte Naubert's novel Hermann of Unna (1788) is seen as being very close to the Schauerroman genre.[10]

While the term "Schauerroman" is sometimes equated with the term "Gothic novel", this is only partially true. Both genres are based on the terrifying side of the Middle Ages, and both frequently feature the same elements (castles, ghost, monster, etc.). However, Schauerroman's key elements are necromancy and secret societies and it is remarkably more pessimistic than the British Gothic novel. All those elements are the basis for Friedrich von Schiller's unfinished novel The Ghost-Seer (1786–1789). The motive of secret societies is also present in the Karl Grosse's Horrid Mysteries (1791–1794) and Christian August Vulpius's Rinaldo Rinaldini, the Robber Captain (1797).[11]

Other early authors and works included Christian Heinrich Spiess, with his works Das Petermännchen (1793), Der alte Überall and Nirgends (1792), Die Löwenritter (1794), and Hans Heiling, vierter und letzter Regent der Erd- Luft- Feuer- und Wasser-Geister (1798); Heinrich von Kleist's short story "Das Bettelweib von Locarno" (1797); and Ludwig Tieck's Der blonde Eckbert (1797) and Der Runenberg (1804).[12]

During the next two decades, the most famous author of Gothic literature in Germany was polymath E. T. A. Hoffmann. His novel The Devil's Elixirs (1815) was influenced by Lewis's novel The Monk, and even mentions it during the book. The novel also explores the motive of doppelgänger, the term coined by another German author (and supporter of Hoffmann), Jean Paul in his humorous novel Siebenkäs (1796–1797). He also wrote an opera based on the Friedrich de la Motte Fouqué's Gothic story Undine, with de la Motte Fouqué himself writing the libretto.[13] Aside from Hoffmann and de la Motte Fouqué, three other important authors from the era were Joseph Freiherr von Eichendorff (The Marble Statue, 1819), Ludwig Achim von Arnim (Die Majoratsherren, 1819), and Adelbert von Chamisso (Peter Schlemihls wundersame Geschichte, 1814).[14]

After them, Wilhelm Meinhold wrote The Amber Witch (1838) and Sidonia von Bork (1847). Also writing in the German language, Jeremias Gotthelf wrote The Black Spider (1842), an allegorical work that used Gothic themes. The last work from German writer Theodor Storm, The Rider on the White Horse (1888), also uses Gothic motives and themes.[15] In the beginning of the 20th century, many German authors wrote works influenced by Schauerroman, including Hanns Heinz Ewers.[16]

Russian Empire

Russian Gothic was not, until recently, viewed as a critical label by Russian critics. If used, the word "gothic" was used to describe (mostly early) works of Fyodor Dostoyevsky. Most critics simply used the tags such as "Romanticism" and "fantastique". Even in relatively new story collection translated as Russian 19th-Century Gothic Tales (from 1984), the editor used the name Фантастический мир русской романтической повести (The Fantastic World of Russian Romanticism Short Story/Novella).[17] However, since the mid-1980s, Russian gothic fiction was discussed in books like The Gothic-Fantastic in Nineteenth-Century Russian Literature, European Gothic: A Spirited Exchange 1760–1960, The Russian Gothic novel and its British antecedents and Goticheskiy roman v Rossii (Gothic Novel in Russia).

The first Russian author whose work can be described as gothic fiction is considered to be Nikolay Mikhailovich Karamzin. Although many of his works feature gothic elements, the first one which is considered to belong purely in the "gothic fiction" label is Ostrov Borngolm (Island of Bornholm) from 1793.[18] The next important early Russian author is Nikolay Ivanovich Gnedich with his novel Don Corrado de Gerrera from 1803, which is set in Spain during the reign of Philip II.[19]

The term "gothic" is sometimes also used to describe the ballads of Vasily Andreyevich Zhukovsky (particularly "Ludmila" (1808) and "Svetlana" (1813)). Also, the following poems are considered to belong in the gothic genre: Meshchevskiy's "Lila", Katenin's "Olga", Pushkhin's "The Bridegroom", Pletnev's "The Gravedigger" and Lermontov's "Demon".[20]

The other authors from the romanticism era include: Antony Pogorelsky (penname of Alexey Alexeyevich Perovsky), Orest Somov, Oleksa Storozhenko,[21] Alexandr Pushkin, Nikolai Alekseevich Polevoy, Mikhail Lermontov (his work Stuss) and Alexander Bestuzhev-Marlinsky.[22] Pushkin is particularly important, as his short story "The Queen of Spades" (1833) was adapted into operas and movies by both Russian and foreign artists. Some parts of Mikhail Yuryevich Lermontov's "A Hero of Our Time" (1840) are also considered to belong in the gothic genre, but they lack the supernatural elements of the other Russian gothic stories.

The key author of the transition from romanticism to realism, Nikolai Vasilievich Gogol, is also one of the most important authors of the romanticism, and has produced a number of works which qualify as gothic fiction. His works include three short story collections, of which each one features a number of stories in the gothic genre, as well as many stories with gothic elements. The collections are: Evenings on a Farm Near Dikanka (1831–1832) with the stories "St John's Eve" and "A Terrible Vengeance"; Arabesques (1835), with the story "The Portrait"; and Mirgorod (1835), with the story "Viy". The last story is probably the most famous, having inspired at least eight movie adaptations (two of which are now considered to be lost), one animated movie, two documentaries, and a video game. Gogol's work is very different from western European gothic fiction, as he is influenced by Ukrainian folklore, Cossack lifestyle and, being a very religious man, Orthodox Christianity.[23][24]

Other authors of Gogol's era included Vladimir Fyodorovich Odoevsky (The Living Corpse, written 1838, published 1844; The Ghost; The Sylphide; and other stories), Count Aleksey Konstantinovich Tolstoy (The Family of the Vourdalak, 1839, and The Vampire, 1841), Mikhail Zagoskin (Unexpected Guests), Józef Sękowski/Osip Senkovsky (Antar), and Yevgeny Baratynsky (The Ring).[22]

After Gogol, the Russian literature saw the rise of the realism, but many authors wrote stories belonging to the gothic fiction territory. Ivan Sergeyevich Turgenev, one of the world's most celebrated realists, wrote Faust (1856), Phantoms (1864), Song of the Triumphant Love (1881), and Clara Milich (1883). Another Russian realist classic, Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoyevsky, incorporated gothic elements in many of his works, although none of his novels are seen as purely gothic.[25] Grigory Petrovich Danilevsky, who wrote historical and early science fiction novels and stories, wrote Mertvec-ubiytsa (Dead Murderer) in 1879. Also, Grigori Alexandrovich Machtet wrote the story "Zaklyatiy kazak".[26]

During the last years of the Russian Empire, in the early 20th century, many authors continued to write in the gothic fiction genre. These include historian and historical fiction writer Alexander Valentinovich Amfiteatrov; Leonid Nikolaievich Andreyev, who developed psychological characterization; symbolist Valery Yakovlevich Bryusov; Alexander Grin; Anton Pavlovich Chekhov;[27] and Aleksandr Ivanovich Kuprin.[26] Nobel Prize winner Ivan Alekseyevich Bunin wrote Dry Valley (1912), which is considered to be influenced by gothic literature.[28] In her monograph on the subject, Muireann Maguire writes, "The centrality of the Gothic-fantastic to Russian fiction is almost impossible to exaggerate, and certainly exceptional in the context of world literature."[29]

The Romantics

Further contributions to the Gothic genre were seen in the work of the Romantic poets. Prominent examples include Coleridge's The Rime of the Ancient Mariner and Christabel as well as Keats' La Belle Dame sans Merci (1819) and Isabella, or the Pot of Basil (1820) which feature mysteriously fey ladies.[30] In the latter poem the names of the characters, the dream visions and the macabre physical details are influenced by the novels of premiere Gothicist Ann Radcliffe.[30] Percy Bysshe Shelley's first published work was the Gothic novel Zastrozzi (1810), about an outlaw obsessed with revenge against his father and half-brother. Shelley published a second Gothic novel in 1811, St. Irvyne; or, The Rosicrucian, about an alchemist who seeks to impart the secret of immortality.

The poetry, romantic adventures, and character of Lord Byron – characterised by his spurned lover Lady Caroline Lamb as 'mad, bad and dangerous to know' – were another inspiration for the Gothic, providing the archetype of the Byronic hero. Byron features, under the codename of 'Lord Ruthven', in Lady Caroline's own Gothic novel: Glenarvon (1816).

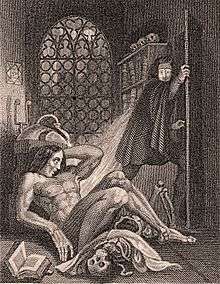

Byron was also the host of the celebrated ghost-story competition involving himself, Percy Bysshe Shelley, Mary Shelley, and John William Polidori at the Villa Diodati on the banks of Lake Geneva in the summer of 1816. This occasion was productive of both Mary Shelley's Frankenstein (1818) and Polidori's The Vampyre (1819). This latter story revives Lamb's Byronic 'Lord Ruthven', but this time as a vampire. The Vampyre has been accounted by cultural critic Christopher Frayling as one of the most influential works of fiction ever written and spawned a craze for vampire fiction and theatre (and latterly film) which has not ceased to this day. Mary Shelley's novel, though clearly influenced by the Gothic tradition, is often considered the first science fiction novel, despite the omission in the novel of any scientific explanation of the monster's animation and the focus instead on the moral issues and consequences of such a creation.

A late example of traditional Gothic is Melmoth the Wanderer (1820) by Charles Maturin, which combines themes of anti-Catholicism with an outcast Byronic hero.[31]

Victorian Gothic

By the Victorian era, Gothic had ceased to be the dominant genre and was dismissed by most critics (in fact the form's popularity as an established genre had already begun to erode with the success of the historical romance popularised by Sir Walter Scott). However, in many ways, it was now entering its most creative phase. Recently readers and critics have begun to reconsider a number of previously overlooked Penny Blood or Penny Dreadful serial fictions by such authors as G.W.M. Reynolds who wrote a trilogy of Gothic horror novels: Faust (1846), Wagner the Wehr-wolf (1847) and The Necromancer (1857).[32] Reynolds was also responsible for The Mysteries of London which has been accorded an important place in the development of the urban as a particularly Victorian Gothic setting, an area within which interesting links can be made with established readings of the work of Dickens and others. Another famous penny dreadful of this era was the anonymously authored Varney the Vampire (1847). The formal relationship between these fictions, serialised for predominantly working class audiences, and the roughly contemporaneous sensation fictions serialised in middle class periodicals is also an area worthy of inquiry.

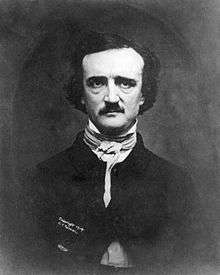

An important and innovative reinterpreter of the Gothic in this period was Edgar Allan Poe. Poe focused less on the traditional elements of gothic stories and more on the psychology of his characters as they often descended into madness. Poe's critics complained about his "German" tales, to which he replied, 'that terror is not of Germany, but of the soul'. Poe, a critic himself, believed that terror was a legitimate literary subject. His story "The Fall of the House of Usher" (1839) explores these 'terrors of the soul' while revisiting classic Gothic tropes of aristocratic decay, death, and madness.[33] The legendary villainy of the Spanish Inquisition, previously explored by Gothicists Radcliffe, Lewis, and Maturin, is based on a true account of a survivor in "The Pit and the Pendulum" (1842). The influence of Ann Radcliffe is also detectable in Poe's "The Oval Portrait" (1842), including an honorary mention of her name in the text of the story.

The influence of Byronic Romanticism evident in Poe is also apparent in the work of the Brontë sisters. Emily Brontë's Wuthering Heights (1847) transports the Gothic to the forbidding Yorkshire Moors and features ghostly apparitions and a Byronic hero in the person of the demonic Heathcliff. The Brontës' fiction is seen by some feminist critics as prime examples of Female Gothic, exploring woman's entrapment within domestic space and subjection to patriarchal authority and the transgressive and dangerous attempts to subvert and escape such restriction. Emily's Cathy and Charlotte Brontë's Jane Eyre are both examples of female protagonists in such a role.[34] Louisa May Alcott's Gothic potboiler, A Long Fatal Love Chase (written in 1866, but published in 1995) is also an interesting specimen of this subgenre.

Elizabeth Gaskell's tales "The Doom of the Griffiths" (1858) "Lois the Witch", and "The Grey Woman" all employ one of the most common themes of Gothic fiction, the power of ancestral sins to curse future generations, or the fear that they will.

The gloomy villain, forbidding mansion, and persecuted heroine of Sheridan Le Fanu's Uncle Silas (1864) shows the direct influence of both Walpole's Otranto and Radcliffe's Udolpho. Le Fanu's short story collection In a Glass Darkly (1872) includes the superlative vampire tale Carmilla, which provided fresh blood for that particular strand of the Gothic and influenced Bram Stoker's vampire novel Dracula (1897). According to literary critic Terry Eagleton, Le Fanu, together with his predecessor Maturin and his successor Stoker, form a subgenre of Irish Gothic, whose stories, featuring castles set in a barren landscape, with a cast of remote aristocrats dominating an atavistic peasantry, represent in allegorical form the political plight of colonial Ireland subjected to the Protestant Ascendancy.[35]

The genre was also a heavy influence on more mainstream writers, such as Charles Dickens, who read Gothic novels as a teenager and incorporated their gloomy atmosphere and melodrama into his own works, shifting them to a more modern period and an urban setting, including Oliver Twist (1837–8), Bleak House (1854) (Mighall 2003) and Great Expectations (1860–61). These pointed to the juxtaposition of wealthy, ordered and affluent civilisation next to the disorder and barbarity of the poor within the same metropolis. Bleak House in particular is credited with seeing the introduction of urban fog to the novel, which would become a frequent characteristic of urban Gothic literature and film (Mighall 2007). His most explicitly Gothic work is his last novel, The Mystery of Edwin Drood, which he did not live to complete and which was published in unfinished state upon his death in 1870. The mood and themes of the Gothic novel held a particular fascination for the Victorians, with their morbid obsession with mourning rituals, mementos, and mortality in general.

The 1880s saw the revival of the Gothic as a powerful literary form allied to fin de siecle, which fictionalized contemporary fears like ethical degeneration and questioned the social structures of the time. Classic works of this Urban Gothic include Robert Louis Stevenson's Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde (1886), Oscar Wilde's The Picture of Dorian Gray (1891), George du Maurier's Trilby (1894), Richard Marsh's The Beetle: A Mystery (1897), Henry James' The Turn of the Screw (1898), and the stories of Arthur Machen. Some of the works of Canadian writer Gilbert Parker also fall into the genre, including the stories in The Lane that Had No Turning (1900).[36]

The most famous Gothic villain ever, Count Dracula, was created by Bram Stoker in his novel Dracula (1897). Stoker's book also established Transylvania and Eastern Europe as the locus classicus of the Gothic.[37] Gaston Leroux's serialized novel The Phantom of the Opera (1909–1910) is another well-known example of gothic fiction from the early twentieth century.

In America, two notable writers of the end of the 19th century, in the Gothic tradition, were Ambrose Bierce and Robert W. Chambers. Bierce's short stories were in the horrific and pessimistic tradition of Poe. Chambers, though, indulged in the decadent style of Wilde and Machen, even to the extent of his inclusion of a character named 'Wilde' in his The King in Yellow.

Precursors to the Gothic

The conventions of Gothic literature did not spring from nowhere into the mind of Horace Walpole. The components that would eventually combine into Gothic literature had a rich history by the time Walpole perpetrated his literary hoax in 1764.

The Mysterious Imagination

Gothic literature is often described with words such as "wonder" and "terror."[38] This sense of wonder and terror, which provides the suspension of disbelief so important to the Gothic—which, except for when it is parodied, even for all its occasional melodrama, is typically played straight, in a self-serious manner—requires the imagination of the reader to be willing to accept the idea that there might be something "beyond that which is immediately in front of us." The mysterious imagination necessary for Gothic literature to have gained any traction had been growing for some time before the advent of the Gothic. The necessity for this came as the known world was beginning to become more explored, reducing the inherent geographical mysteries of the world. The edges of the map were being filled in, and no one was finding any dragons. The human mind required a replacement.[39] Clive Bloom theorizes that this void in the collective imagination was critical in the development of the cultural possibility for the rise of the Gothic tradition.[40]

Medievalism

The setting of most early Gothic works was a medieval one, but this had been a common theme long before Walpole. In Britain especially, there was a desire to reclaim a shared past. This obsession frequently led to extravagant architectural displays, and sometimes mock tournaments were held. It was not merely in literature that a medieval revival made itself felt, and this too contributed to a culture ready to accept a perceived medieval work in 1764.[39]

The Macabre and the Morbid

The Gothic often uses scenery of decay, death, and morbidity to achieve its effects (especially in the Italian Horror school of Gothic). However, Gothic literature was not the origin of this tradition; indeed it was far older. The corpses, skeletons, and churchyards so commonly associated with the early Gothic were popularized by the Graveyard Poets, and were also present in novels such as Daniel Defoe's Journal of the Plague Year, which contains comical scenes of plague carts and piles of plague corpses. Even earlier, poets like Edmund Spenser evoked a dreary and sorrowful mood in such poems as Epithalamion.[39]

An Emotional Aesthetic to Tie it Together

All of the aspects of pre-Gothic literature mentioned above occur to some degree in the Gothic, but even taken together, they still fall short of true Gothic.[39] What was lacking was an aesthetic, which would serve to tie the elements together. Bloom notes that this aesthetic must take the form of a theoretical or philosophical core, which is necessary to "sav[e] the best tales from becoming mere anecdote or incoherent sensationalism."[41] In this particular case, the aesthetic needed to be an emotional one, which was finally provided by Edmund Burke’s 1757 work, A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and the Beautiful, which "finally codif[ied] the gothic emotional experience."[42] Specifically, Burke's thoughts on the Sublime, Terror, and Obscurity were most applicable. These sections can be summarized thus: the Sublime is that which is or produces the "strongest emotion which the mind is capable of feeling,"; the Sublime is most often evoked by Terror; and to cause Terror we need some amount of Obscurity–we can’t know everything about that which is inducing Terror–or else "a great deal of the apprehension vanishes"; Obscurity is necessary in order to experience the Terror of the unknown.[39] Bloom asserts that Burke's descriptive vocabulary was essential to the Romantic works that eventually informed the Gothic.

Parody

The excesses, stereotypes, and frequent absurdities of the traditional Gothic made it rich territory for satire.[43] The most famous parody of the Gothic is Jane Austen's novel Northanger Abbey (1818) in which the naive protagonist, after reading too much Gothic fiction, conceives herself a heroine of a Radcliffian romance and imagines murder and villainy on every side, though the truth turns out to be much more prosaic. Jane Austen's novel is valuable for including a list of early Gothic works since known as the Northanger Horrid Novels. These books, with their lurid titles, were once thought to be the creations of Jane Austen's imagination, though later research by Michael Sadleir and Montague Summers confirmed that they did actually exist and stimulated renewed interest in the Gothic. They are currently all being reprinted.[44]

Another example of Gothic parody in a similar vein is The Heroine by Eaton Stannard Barrett (1813). Cherry Wilkinson, a fatuous female protagonist with a history of novel-reading, fancies herself as the heroine of a Gothic romance. She perceives and models reality according to the stereotypes and typical plot structures of the Gothic novel, leading to a series of absurd events culminating in catastrophe. After her downfall, her affectations and excessive imaginations become eventually subdued by the voice of reason in the form of Stuart, a paternal figure, under whose guidance the protagonist receives a sound education and correction of her misguided taste[45]

Post-Victorian legacy

Pulp

Notable English twentieth-century writers in the Gothic tradition include Algernon Blackwood, William Hope Hodgson, M. R. James, Hugh Walpole, and Marjorie Bowen. In America pulp magazines such as Weird Tales reprinted classic Gothic horror tales from the previous century, by such authors as Poe, Arthur Conan Doyle, and Edward Bulwer-Lytton and printed new stories by modern authors featuring both traditional and new horrors.[46] The most significant of these was H. P. Lovecraft who also wrote an excellent conspectus of the Gothic and supernatural horror tradition in his Supernatural Horror in Literature (1936) as well as developing a Mythos that would influence Gothic and contemporary horror well into the 21st century. Lovecraft's protégé, Robert Bloch, contributed to Weird Tales and penned Psycho (1959), which drew on the classic interests of the genre. From these, the Gothic genre per se gave way to modern horror fiction, regarded by some literary critics as a branch of the Gothic[47] although others use the term to cover the entire genre.

New Gothic Romances

Gothic Romances of this description became popular during the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s, with authors such as Phyllis A. Whitney, Joan Aiken, Dorothy Eden, Victoria Holt, Barbara Michaels, Mary Stewart, and Jill Tattersall. Many featured covers depicting a terror-stricken woman in diaphanous attire in front of a gloomy castle, often with a single lit window. Many were published under the Paperback Library Gothic imprint and were marketed to a female audience. Though the authors were mostly women, some men wrote Gothic romances under female pseudonyms. For instance the prolific Clarissa Ross and Marilyn Ross were pseudonyms for the male writer Dan Ross and Frank Belknap Long published Gothics under his wife's name, Lyda Belknap Long. Another example is British writer Peter O'Donnell, who wrote under the pseudonym Madeleine Brent. Outside of companies like Lovespell, who carry Colleen Shannon, very few books seem to be published using the term today.

Southern Gothic

The genre also influenced American writing to create the Southern Gothic genre, which combines some Gothic sensibilities (such as the grotesque) with the setting and style of the Southern United States. Examples include William Faulkner, Eudora Welty, Truman Capote, Flannery O'Connor, Davis Grubb, and Harper Lee.[48]

Other contemporary Gothic

Contemporary American writers in this tradition include Joyce Carol Oates, in such novels as Bellefleur and A Bloodsmoor Romance and short story collections such as Night-Side (Skarda 1986b) and Raymond Kennedy in his novel Lulu Incognito.

The Southern Ontario Gothic applies a similar sensibility to a Canadian cultural context. Robertson Davies, Alice Munro, Barbara Gowdy, Timothy Findley and Margaret Atwood have all produced works that are notable exemplars of this form.

Another writer in this tradition was Henry Farrell whose best-known work was the Hollywood horror novel What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? (1960). Farrel's novels spawned a subgenre of "Grande Dame Guignol" in the cinema, dubbed the "psycho-biddy" genre.

Modern horror

Many modern writers of horror (or indeed other types of fiction) exhibit considerable Gothic sensibilities—examples include the works of Anne Rice, Stella Coulson, Susan Hill, Poppy Z. Brite and Neil Gaiman as well as some of the sensationalist works of Stephen King[49][50] Thomas M. Disch's novel The Priest (1994) was subtitled A Gothic Romance, and was partly modelled on Matthew Lewis' The Monk.[51] The Romantic strand of Gothic was taken up in Daphne du Maurier's Rebecca (1938) which is considered by some to be in many respects a reworking of Charlotte Brontë's Jane Eyre.[52] Other books by du Maurier, such as Jamaica Inn (1936), also display Gothic tendencies. Du Maurier's work inspired a substantial body of "female Gothics", concerning heroines alternately swooning over or being terrified by scowling Byronic men in possession of acres of prime real estate and the appertaining droit du seigneur.

The Gothic in education

Educators in literary, cultural, and architectural studies appreciate the Gothic as an area that facilitates the investigation of the beginnings of scientific certainty. As Carol Senf has stated, "the Gothic was […] a counterbalance produced by writers and thinkers who felt limited by such a confident worldview and recognized that the power of the past, the irrational, and the violent continue to hold sway in the world."[53] As such, the Gothic helps students better understand their own doubts about the self-assurance of today's scientists. Scotland is the location of what was probably the world´s first postgraduate program to exclusively consider the genre: the MLitt in the Gothic Imagination at the University of Stirling, which first recruited in 1996.[54]

Other media

The themes of the literary Gothic have been translated into other media. The early 1970s saw a Gothic Romance comic book mini-trend with such titles as DC Comics' The Dark Mansion Of Forbidden Love and The Sinister House of Secret Love, Charlton Comics' Haunted Love, Curtis Magazines' Gothic Tales of Love, and Atlas/Seaboard Comics' one-shot magazine Gothic Romances.

There was a notable revival in 20th-century Gothic horror films such the classic Universal Horror films of the 1930s, Hammer Horror, and Roger Corman's Poe cycle.[55] In Hindi cinema, the Gothic tradition was combined with aspects of Indian culture, particularly reincarnation, to give rise to an "Indian Gothic" genre, beginning with the films Mahal (1949) and Madhumati (1958).[56] Modern Gothic horror films include Sleepy Hollow, Interview with the Vampire, Underworld, The Wolfman, From Hell, Dorian Gray, Let The Right One In and The Woman in Black.

The 1960s Gothic television series Dark Shadows borrowed liberally from the Gothic tradition and featured elements such as haunted mansions, vampires, witches, doomed romances, werewolves, obsession, and madness.

The Showtime TV series Penny Dreadful brings many classic gothic characters together in a psychological thriller that takes place in the dark corners of Victorian London (2014 debut).

Twentieth-century rock music also had its Gothic side. Black Sabbath's 1970 debut album created a dark sound different from other bands at the time and has been called the first ever "Goth-rock" record.[57] Themes from Gothic writers such as H. P. Lovecraft were also used among gothic rock and heavy metal bands, especially in black metal, thrash metal (Metallica's The Call of Ktulu), death metal, and gothic metal. For example, heavy metal musician King Diamond delights in telling stories full of horror, theatricality, satanism and anti-Catholicism in his compositions.[58]

Various video games feature Gothic horror themes and plots. For example, the Castlevania series typically involves a hero of the Belmont lineage exploring a dark, old castle, fighting vampires, werewolves, Frankenstein's monster, and other Gothic monster staples, culminating in a battle against Dracula himself. Others, such as Ghosts'n Goblins feature a campier parody of Gothic fiction.

In role-playing games, the pioneering 1983 Dungeons & Dragons adventure Ravenloft instructs the players to defeat the vampire Strahd von Zarovich, who pines for his dead lover. It has been acclaimed as one of the best role-playing adventures of all time, and even inspired an entire fictional world of the same name.

Elements of Gothic fiction

- Virginal maiden – young, beautiful, pure, innocent, kind, virtuous and sensitive. Usually starts out with a mysterious past and it is later revealed that she is the daughter of an aristocratic or noble family.

- Matilda in The Castle of Otranto – She is determined to give up Theodore, the love of her life, for her cousin’s sake. Matilda always puts others first before herself, and always believes the best in others.

- Adeline in The Romance of the Forest – "Her wicked Marquis, having secretly immured Number One (his first wife), has now a new and beautiful wife, whose character, alas! Does not bear inspection."[59] As this review states, the virginal maiden character is above inspection because her personality is flawless. Hers is a virtuous character whose piety and unflinching optimism cause all to fall in love with her.

- Older, foolish woman

- Hippolita in The Castle of Otranto – Hippolita is depicted as the obedient wife of her tyrant husband who "would not only acquiesce with patience to divorce, but would obey, if it was his pleasure, in endeavouring to persuade Isabelle to give him her hand".[60] This shows how weak women are portrayed as they are completely submissive, and in Hippolita’s case, even support polygamy at the expense of her own marriage.[61]

- Madame LaMotte in The Romance of the Forest – naively assumes that her husband is having an affair with Adeline. Instead of addressing the situation directly, she foolishly lets her ignorance turn into pettiness and mistreatment of Adeline.

- Hero

- Theodore in The Castle of Otranto – he is witty, and successfully challenges the tyrant, saves the virginal maid without expectations

- Theodore in The Romance of the Forest – saves Adeline multiple times, is virtuous, courageous and brave, self-sacrificial

- Tyrant/villain

- Manfred in The Castle of Otranto – unjustly accuses Theodore of murdering Conrad. Tries to put his blame onto others. Lies about his motives for attempting to divorce his wife and marry his late son’s fiancé.

- The Marquis in The Romance of the Forest – attempts to get with Adeline even though he is already married, attempts to rape Adeline, blackmails Monsieur LaMotte.

- Vathek – Ninth Caliph of the Abassides, who ascended to the throne at an early age. His figure was pleasing and majestic, but when angry, his eyes became so terrible that "the wretch on whom it was fixed instantly fell backwards and sometimes expired". He was addicted to women and pleasures of the flesh, so he ordered five palaces to be built: the five palaces of the senses. Although he was an eccentric man, learned in the ways of science, physics, and astrology, he loved his people. His main greed, however, was thirst for knowledge. He wanted to know everything. This is what led him on the road to damnation."[62]

- Bandits/ruffians

- They appear in several Gothic novels including The Romance of the Forest in which they kidnap Adeline from her father.

- Clergy – always weak, usually evil

- Father Jerome in The Castle of Otranto – Jerome, though not evil, is certainly weak as he gives up his son when he is born and leaves his lover.

- Ambrosio in The Monk – Evil and weak, this character stoops to the lowest levels of corruption including rape and incest.

- Mother Superior in The Romance of the Forest – Adeline fled from this convent because the sisters weren’t allowed to see sunlight. Highly oppressive environment.

- The setting

- The plot is usually set in a castle, an abbey, a monastery, or some other, usually religious edifice, and it is acknowledged that this building has secrets of its own. It is this gloomy and frightening scenery, which sets the scene for what the audience should expect. The importance of setting is noted in a London review of the Castle of Otranto, "He describes the country towards Otranto as desolate and bare, extensive downs covered with thyme, with occasionally the dwarf holly, the rosa marina, and lavender, stretch around like wild moorlands…Mr. Williams describes the celebrated Castle of Otranto as "an imposing object of considerable size…has a dignified and chivalric air. A fitter scene for his romance he probably could not have chosen." Similarly, De Vore states, "The setting is greatly influential in Gothic novels. It not only evokes the atmosphere of horror and dread, but also portrays the deterioration of its world. The decaying, ruined scenery implies that at one time there was a thriving world. At one time the abbey, castle, or landscape was something treasured and appreciated. Now, all that lasts is the decaying shell of a once thriving dwelling."[63] Thus, without the decrepit backdrop to initiate the events, the Gothic novel would not exist.

Elements found especially in American Gothic fiction include:

- Night journeys are a common element seen throughout Gothic literature. They can occur in almost any setting, but in American literature are more commonly seen in the wilderness, forest or any other area that is devoid of people.

- Evil characters are also seen in Gothic literature and especially American Gothic. Depending on the time period that the work is written about, the evil characters could be characters like Native Americans, trappers, gold miners etc.

- American Gothic novels also tend to deal with a "madness" in one or more of the characters and carry that theme throughout the novel. In his novel Edgar Huntly or Memoirs of a Sleepwalker, Charles Brockden Brown writes about two characters who slowly become more and more deranged as the novel progresses.

- Miraculous survivals are elements within American Gothic literature in which a character or characters will somehow manage to survive some feat that should have led to their demise.

- In American Gothic novels it is also typical that one or more of the characters will have some sort of supernatural powers. In Brown's Edgar Huntly or Memoirs of a Sleepwalker, the main character, Huntly, is able to face and kill not one, but two panthers.

- An element of fear is another characteristic of American Gothic literature. This is typically connected to the unknown and is generally seen throughout the course of the entire novel. This can also be connected to the feeling of despair that characters within the novel are overcome by. This element can lead characters to commit heinous crimes. In the case of Brown's character Edgar Huntly, he experiences this element when he contemplates eating himself, eats an uncooked panther, and drinks his own sweat.

- Psychological overlay is an element that is connected to how characters within an American Gothic novel are affected by things like the night and their surroundings. An example of this would be if a character was in a maze-like area and a connection was made to the maze that their minds represented.

Role of architecture and setting in the Gothic novel

Gothic literature is intimately associated with the Gothic Revival architecture of the same era. In a way similar to the Gothic revivalists' rejection of the clarity and rationalism of the neoclassical style of the Enlightened Establishment, the literary Gothic embodies an appreciation of the joys of extreme emotion, the thrills of fearfulness and awe inherent in the sublime, and a quest for atmosphere.

The ruins of Gothic buildings gave rise to multiple linked emotions by representing the inevitable decay and collapse of human creations – thus the urge to add fake ruins as eyecatchers in English landscape parks. English Gothic writers often associated medieval buildings with what they saw as a dark and terrifying period, characterized by harsh laws enforced by torture, and with mysterious, fantastic, and superstitious rituals. In literature such Anti-Catholicism had a European dimension featuring Roman Catholic institutions such as the Inquisition (in southern European countries such as Italy and Spain).

Just as elements of Gothic architecture were borrowed during the Gothic Revival period in architecture, ideas about the Gothic period and Gothic period architecture were often used by Gothic novelists. Architecture itself played a role in the naming of Gothic novels, with many titles referring to castles or other common Gothic buildings. This naming was followed up with many Gothic novels often set in Gothic buildings, with the action taking place in castles, abbeys, convents and monasteries, many of them in ruins, evoking "feelings of fear, surprise, confinement". This setting of the novel, a castle or religious building, often one fallen into disrepair, was an essential element of the Gothic novel. Placing a story in a Gothic building served several purposes. It drew on feelings of awe, it implied the story was set in the past, it gave an impression of isolation or being cut off from the rest of the world and it drew on the religious associations of the Gothic style. This trend of using Gothic architecture began with The Castle of Otranto and was to become a major element of the genre from that point forward.[4]

Besides using Gothic architecture as a setting, with the aim of eliciting certain associations from the reader, there was an equally close association between the use of setting and the storylines of Gothic novels, with the architecture often serving as a mirror for the characters and the plot lines of the story.[64] The buildings in the Castle of Otranto, for example, are riddled with underground tunnels, which the characters use to move back and forth in secret. This secret movement mirrors one of the plots of the story, specifically the secrets surrounding Manfred’s possession of the castle and how it came into his family.[65] The setting of the novel in a Gothic castle was meant to imply not only a story set in the past but one shrouded in darkness.

In William Thomas Beckford's The History of the Caliph Vathek, architecture was used to both illustrate certain elements of Vathek's character and also warn about the dangers of over-reaching. Vathek’s hedonism and devotion to the pursuit of pleasure are reflected in the pleasure wings he adds on to his castle, each with the express purpose of satisfying a different sense. He also builds a tall tower in order to further his quest for knowledge. This tower represents Vathek's pride and his desire for a power that is beyond the reach of humans. He is later warned that he must destroy the tower and return to Islam or else risk dire consequences. Vathek’s pride wins out and, in the end, his quest for power and knowledge ends with him confined to Hell.[66]

In the Castle of Wolfenbach the castle that Matilda seeks refuge at while on the run is believed to be haunted. Matilda discovers it is not ghosts but the Countess of Wolfenbach who lives on the upper floors and who has been forced into hiding by her husband, the Count. Matilda’s discovery of the Countess and her subsequent informing others of the Countess's presence destroys the Count's secret. Shortly after Matilda meets the Countess the Castle of Wolfenbach itself is destroyed in a fire, mirroring the destruction of the Count's attempts to keep his wife a secret and how his plots throughout the story eventually lead to his own destruction.[67]

The major part of the action in the Romance of the Forest is set in an abandoned and ruined abbey and the building itself served as a moral lesson, as well as a major setting for and mirror of the action in the novel. The setting of the action in a ruined abbey, drawing on Burke’s aesthetic theory of the sublime and the beautiful established the location as a place of terror and of safety. Burke argued the sublime was a source of awe or fear brought about by strong emotions such as terror or mental pain. On the other end of the spectrum was the beautiful, which were those things that brought pleasure and safety. Burke argued that the sublime was the more preferred to the two. Related to the concepts of the sublime and the beautiful is the idea of the picturesque, introduced by William Gilpin, which was thought to exist between the two other extremes. The picturesque was that which continued elements of both the sublime and the beautiful and can be thought of as a natural or uncultivated beauty, such as a beautiful ruin or a partially overgrown building. In Romance of the Forest Adeline and the La Mottes live in constant fear of discovery by either the police or Adeline’s father and, at times, certain characters believe the castle to be haunted. On the other hand, the abbey also serves as a comfort, as it provides shelter and safety to the characters. Finally, it is picturesque, in that it was a ruin and serves as a combination of both the natural and the human. By setting the story in the ruined abbey, Radcliffe was able to use architecture to draw on the aesthetic theories of the time and set the tone of the story in the minds of the reader. As with many of the buildings in Gothic novels, the abbey also has a series of tunnels. These tunnels serve as both a hiding place for the characters and as a place of secrets. This was mirrored later in the novel with Adeline hiding from the Marquis de Montalt and the secrets of the Marquis, which would eventually lead to his downfall and Adeline's salvation.[68]

Architecture served as an additional character in many Gothic novels, bringing with it associations to the past and to secrets and, in many cases, moving the action along and foretelling future events in the story.

The female Gothic and the supernatural explained

Characterized by its castles, dungeons, gloomy forests and hidden passages, from the Gothic novel genre emerged the Female Gothic. Guided by the works of authors such as Ann Radcliffe, Mary Shelley and Charlotte Brontë, the Female Gothic permitted the introduction of feminine societal and sexual desires into Gothic texts. It has been said that medieval society, on which some Gothic texts are based, granted women writers the opportunity to attribute "features of the mode [of Gothicism] as the result of the suppression of female sexuality, or else as a challenge to the gender hierarchy and values of a male-dominated culture".[69]

Significantly, with the development of the Female Gothic came the literary technique of explaining the supernatural. The Supernatural Explained – as this technique was aptly named – is a recurring plot device in Radcliffe’s The Romance of the Forest. The novel, published in 1791, is among Radcliffe’s earlier works. The novel sets up suspense for horrific events, which all have natural explanations.

An eighteenth-century response to the novel from the Monthly Review reads: "We must hear no more of enchanted forests and castles, giants, dragons, walls of fire and other ‘monstrous and prodigious things;’ – yet still forests and castles remain, and it is still within the province of fiction, without overstepping the limits of nature, to make use of them for the purpose of creating surprise."[70]

Radcliffe’s use of Supernatural Explained is characteristic of the Gothic author. The female protagonists pursued in these texts are often caught in an unfamiliar and terrifying landscape, delivering higher degrees of horror. The end result, however, is the explained supernatural, rather than terrors familiar to women such as rape or incest, or the expected ghosts or haunted castles.

In Radcliffe’s The Romance of the Forest, one may follow the female protagonist, Adeline, through the forest, hidden passages and abbey dungeons, "without exclaiming, ‘How these antique towers and vacant courts/ chill the suspended soul, till expectation wears the cast of fear!"[70]

The decision of Female Gothic writers to supplement true supernatural horrors with explained cause and effect transforms romantic plots and Gothic tales into common life and writing. Rather than establish the romantic plot in impossible events Radcliffe strays away from writing "merely fables, which no stretch of fancy could realize."[71]

English scholar Chloe Chard’s published introduction to The Romance of the Forest refers to the "promised effect of terror". The outcome, however, "may prove less horrific than the novel has originally suggested". Radcliffe sets up suspense throughout the course of the novel, insinuating a supernatural or superstitious cause to the mysterious and horrific occurrences of the plot. However, the suspense is relieved with the Supernatural Explained.

For example, Adeline is reading the illegible manuscripts she found in her bedchamber’s secret passage in the abbey when she hears a chilling noise from beyond her doorway. She goes to sleep unsettled, only to awake and learn that what she assumed to be haunting spirits were actually the domestic voices of the servant, Peter. La Motte, her caretaker in the abbey, recognizes the heights to which her imagination reached after reading the autobiographical manuscripts of a past murdered man in the abbey.

- "‘I do not wonder, that after you had suffered its terrors to impress your imagination, you fancied you saw specters, and heard wondrous noises.’ La Motte said.

- ‘God bless you! Ma’amselle,’ said Peter.

- ‘I’m sorry I frightened you so last night.’

- ‘Frightened me,’ said Adeline; ‘how was you concerned in that?’

He then informed her, that when he thought Monsieur and Madame La Motte were asleep, he had stolen to her chamber door... that he had called several times as loudly as he dared, but receiving no answer, he believed she was asleep... This account of the voice she had heard relieved Adeline’s spirits; she was even surprised she did not know it, till remembering the perturbation of her mind for some time preceding, this surprise disappeared."[72]

While Adeline is alone in her characteristically Gothic chamber, she detects something supernatural, or mysterious about the setting. However, the "actual sounds that she hears are accounted for by the efforts of the faithful servant to communicate with her, there is still a hint of supernatural in her dream, inspired, it would be seem, by the fact that she is on the spot of her father’s murder and that his unburied skeleton is concealed in the room next hers".[73]

The supernatural here is indefinitely explained, but what remains is the "tendency in the human mind to reach out beyond the tangible and the visible; and it is in depicting this mood of vague and half-defined emotion that Mrs. Radcliffe excels".[73]

Transmuting the Gothic novel into a comprehensible tale for the imaginative eighteenth-century woman was useful for the Female Gothic writers of the time. Novels were an experience for these women who had no outlet for a thrilling excursion. Sexual encounters and superstitious fantasies were idle elements of the imagination. However, the use of Female Gothic and Supernatural Explained, are a "good example of how the formula [Gothic novel] changes to suit the interests and needs of its current readers".

In many respects, the novel’s "current reader" of the time was the woman who, even as she enjoyed such novels, would feel that she had to "[lay] down her book with affected indifference, or momentary shame,"[74] according to Jane Austen, author of Northanger Abbey. The Gothic novel shaped its form for female readers to "turn to Gothic romances to find support for their own mixed feelings".[75]

Following the characteristic Gothic Bildungsroman-like plot sequence, the Female Gothic allowed its readers to graduate from "adolescence to maturity,"[76] in the face of the realized impossibilities of the supernatural. As female protagonists in novels like Adeline in The Romance of the Forest learn that their superstitious fantasies and terrors are replaced with natural cause and reasonable doubt, the reader may understand the true position of the heroine in the novel:

"The heroine possesses the romantic temperament that perceives strangeness where others see none. Her sensibility, therefore, prevents her from knowing that her true plight is her condition, the disability of being female."[76]

Another text in which the heroine of the Gothic novel encounters the Supernatural Explained is The Castle of Wolfenbach (1793) by Gothic author Eliza Parsons. This Female Gothic text by Parsons is listed as one of Catherine Morland's Gothic texts in Austen's Northanger Abbey. The heroine in The Castle of Wolfenbach, Matilda, seeks refuge after overhearing a conversation in which her Uncle Weimar speaks of plans to rape her. Matilda finds asylum in the Castle of Wolfenbach: a castle inhabited by old married caretakers who claim that the second floor is haunted. Matilda, being the courageous heroine, decides to explore the mysterious wing of the Castle.

Bertha, wife of Joseph, (caretakers of the castle) tells Matilda of the "other wing": "Now for goodness sake, dear madam, don't go no farther, for as sure as you are alive, here the ghosts live, for Joseph says he often sees lights and hears strange things."[77]

However, as Matilda ventures through the castle, she finds that the wing is not haunted by ghosts and rattling chains, but rather, the Countess of Wolfenbach. The supernatural is explained, in this case, ten pages into the novel, and the natural cause of the superstitious noises is a Countess in distress. Characteristic of the Female Gothic, the natural cause of terror is not the supernatural, but rather female disability and societal horrors: rape, incest and the threatening control of the male antagonist.

See also

Notes

- ↑ Punter (2004), p. 178

- ↑ Fuchs (2004), p. 106

- ↑ Scott, Walter (1870). Clara Reeve from Lives of the Eminent Novelists and Dramatists. London: Frederick Warne. pp. 545–550.

- 1 2 Dr. Lillia Melani. "Ann Radcliffe" (PDF). Retrieved May 3, 2012.

- ↑ David Cody, "Ann Radcliffe: An Evaluation", The Victorian Web: An Overview, July 2000.

- ↑ The New Monthly Magazine 7, 1826, pp 145–52

- ↑ Wright (2019) pp35-56

- ↑ Birkhead (1921).

- ↑ Wright (2008) pp 57–73

- ↑ Cussack, Barry, p. 10-16

- ↑ Cussack, Barry, p. 10-17

- ↑ Hogle, p. 65-69

- ↑ Hogle, p. 105-122

- ↑ Cussack, Barry, p. 91. 118–123

- ↑ Cussack, Barry, p. 26

- ↑ Cussack, Barry, p. 23

- ↑ Cornwell (1999). Introduction

- ↑ Cornwell (1999). Derek Offord: Karamzin's Gothic Tale, p. 37-58

- ↑ Cornwell (1999). Alessandra Tosi: At the origins of the Russian gothic novel, p. 59-82

- ↑ Cornwell (1999).Michael Pursglove: Does Russian gothic verse exist, p. 83-102

- ↑ Krys Svitlana, “Folklorism in Ukrainian Gotho-Romantic Prose: Oleksa Storozhenko’s Tale About Devil in Love (1861).” Folklorica: Journal of the Slavic and East European Folklore Association 16 (2011): pp. 117-138

- 1 2 Horner (2002). Neil Cornwell: European gothic and the 19th-century gothic literature , p. 59-82

- ↑ Simpson, circa p. 21

- ↑ Cornwell (1999). Neil Cornwell, p. 189-234

- ↑ Cornwell (1999). p. 211-256

- 1 2 Butuzov

- ↑ Cornwell (1999). p. 257

- ↑ Peterson, p. 36

- ↑ Muireann Maguire, Stalin's Ghosts: Gothic Themes in Early Soviet Literature (Peter Lang Publishing, 2012; ISBN 3-0343-0787-X), p. 14.

- 1 2 Skarda and Jaffe 1981: 33–5, 132–3

- ↑ Varma 1986

- ↑ Baddeley (2002) pp143-4)

- ↑ (Skarda and Jaffe (1981) pp181-2

- ↑ Jackson (1981) pp123-29)

- ↑ Eagleton, 1995.

- ↑ Rubio, Jen (2015). "Introduction" to The Lane that Had No Turning, and Other Tales Concerning the People of Pontiac. Oakville, ON: Rock's Mills Press. pp. vii – viii. ISBN 978-0-9881293-7-5.

- ↑ Mighall, 2003.

- ↑ "Terror and Wonder the Gothic Imagination". The British Library. British Library. Retrieved 26 March 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Early and Pre-Gothic Literary Conventions & Examples". Spooky Scary Skeletons Literary and Horror Society. Spooky Scary Society. 31 October 2015. Retrieved 26 March 2016.

- ↑ Bloom, Clive (2010). Gothic Histories: The Taste for Terror, 1764 to Present. London: Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 2.

- ↑ Bloom, Clive (2010). Gothic Histories: The Taste for Terror, 1764 to Present. London: Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 8.

- ↑ "Early and Pre-Gothic Literary Conventions & Examples". Spooky Scary Skeletons Literary and Horror Society. Spooky Scary Society. 31 October 2016. Retrieved 26 March 2016.

- ↑ Skarda 1986

- ↑ Wright (2007) pp29-32).

- ↑ Skarda (1986)

- ↑ Goulart (1986)

- ↑ (Wisker (2005) pp232-33)

- ↑ Skarda and Jaffe (1981) pp418-56)

- ↑ Skarda and Jaffe (1981) pp464-5, p478

- ↑ Davenport-Hines (1998) pp357-8).

- ↑ Linda Parent Lesher, The Best Novels of the Nineties: A Reader's Guide. McFarland, 2000 ISBN 0-7864-0742-5, (p. 267).

- ↑ Yardley, Jonathan (16 March 2004). "Du Maurier's 'Rebecca,' A Worthy 'Eyre' Apparent". The Washington Post.

- ↑ Carol Senf, "Why We Need the Gothic in a Technological World," in: Humanistic Perspectives in a Technological World, ed. Richard Utz, Valerie B. Johnson, and Travis Denton (Atlanta: School of Literature, Media, and Communication, Georgia Institute of Technology, 2014), pp. 31–32.

- ↑ Hughes, William (2012). Historical Dictionary of Gothic Literature. Scarecrow Press.

- ↑ Davenport-Hines (1998) pp355-8)

- ↑ Mishra, Vijay (2002). Bollywood cinema: temples of desire. Routledge. pp. 49–57. ISBN 0-415-93014-6

- ↑ Baddeley (2002) p264

- ↑ Baddeley (2002) p265

- ↑ Lang, Andrew (July 1900). "Mrs. Radcliffe's Novels". Cornhill Magazine (9:49).

- ↑ Walpole, Horace (1764). The Castle of Otranto. Penguin.

- ↑ "How are Women Depicted and Treated in Gothic Novels".

- ↑ Melville, Lewis (27 November 1909). "Vathek". Athenaeum (4283).

- ↑ De Vore, David. "The Gothic Novel". The Gothic Novel.

- ↑ Bayer-Berenbaum, L. 1982. The Gothic Imagination: Expansion in Gothic Literature and Art. Rutherford: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press.

- ↑ Walpole, H. 1764 (1968). The Castle of Otranto. Reprinted in Three Gothic Novels. London: Penguin Press

- ↑ Beckford, W. 1782 (1968). The History of the Caliph Vathek. Reprinted in Three Gothic Novels. London: Penguin Press.

- ↑ Parsons, E. 1793 (2006). The Castle of Wolfenbach. Chicago: Valencourt Press.

- ↑ Radcliffe, A. 1791 (2009). The Romance of the Forest. Chicago: Valencourt Press.

- ↑ M.H. Abrams, A Glossary of Literary Terms, Ninth Edition, Wadsworth Cengage Learning, 2009.

- 1 2 Hookham "The Romance of the Forest: interspersed with some Pieces of Poetry." Monthly Review, p.82, May 1973.

- ↑ Hay-Market's Belle Assemblee; or Court and fashionable magazine, p. 39, July 1809.

- ↑ Radcliffe The Romance of the Forest, Oxford University Press, 1986.

- 1 2 McIntyre "Were the "Gothic Novels" Gothic?" PMLA, vol. 36, No. 4, 1921.

- ↑ "Austen's Northanger Abbey", Second Edition, Broadview, 2002.

- ↑ Ronald "Terror Gothic: Nightmare and Dream in Ann Radcliffe and Charlotte Bronte", The Female Gothic, Ed. Fleenor, Eden Press Inc, 1983.

- 1 2 Nichols "Place and Eros in Radcliffe", Lewis and Bronte, The Female Gothic, Ed. Fleenor, Eden Press Inc., 1983.

- ↑ Parsons. The Castle of Wolfenbach, Valancourt Books, Kansas City, 2007.

References

- Baddeley, Gavin (2002). Goth Chic. London: Plexus. ISBN 978-0-85965-382-4.

- Baldick, Chris (1993)Introduction, in The Oxford Book of Gothic Tales. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Birkhead, Edith (1921). The Tale of Terror.

- Bloom, Clive (2007). Gothic Horror: A Guide for Students and Readers. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Botting, Fred (1996). Gothic. London: Routledge.

- Brown, Marshall (2005). The Gothic Text. Stanford, CA: Stanford UP.

- Butuzov, A.E. (2008). Russkaya goticheskaya povest XIX Veka.

- Charnes, Linda (2010). Shakespeare and the Gothic Strain. Vol. 38, pp. 185

- Clery, E.J. (1995). The Rise of Supernatural Fiction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Cornwell, Neil (1999), The Gothic-Fantastic in Nineteenth-Century Russian Literature, Amsterdam; Atlanta, GA: Rodopi, Studies in Slavic Literature and Poetics, volume 33.

- Cook, Judith (1980). Women in Shakespeare. London: Harrap & Co. Ltd.

- Cusack A.,Barry M. (2012). Popular Revenants: The German Gothic and Its International Reception, 1800–2000. Camden House

- Davenport-Hines, Richard (1998) Gothic: 400 Years of Excess, Horror, Evil and Ruin. London: Fourth Estate.

- Davison, Carol Margaret (2009) Gothic Literature 1764–1824. Cardiff: University of Wales Press.

- Drakakis, John & Dale Townshend (2008). Gothic Shakespeares. New York: Routledge.

- Eagleton, Terry (1995). Heathcliff and the Great Hunger. NY: Verso.

- Fuchs, Barbara, (2004), Romance. London: Routledge.

- Gamer, Michael, (2006), Romanticism and the Gothic. Genre, Reception and Canon Formation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Gibbons, Luke, (2004), Gaelic Gothic. Galway: Arlen House.

- Gilbert, Sandra and Susan Gubar (1979). The Madwoman in the Attic. ISBN 0-300-08458-7

- Goulart, Ron (1986) "The Pulps" in Jack Sullivan (ed) The Penguin Encyclopedia of Horror and the Supernatural: 337-40.

- Grigorescu, George (2007) . Long Journey Inside The Flesh. Bucharest, Romania ISBN 978-0-8059-8468-2

- Hadji, Robert (1986) "Jean Ray" in The Penguin Encyclopedia of Horror and the Supernatural edited by Jack Sullivan.

- Haggerty, George (2006). Queer Gothic. Urbana, IL: Illinois UP.

- Halberstam, Judith (1995). Skin Shows. Durham, NC: Duke UP.

- Hogle, J.E. (2002). The Cambridge Companion to Gothic Fiction. Cambridge University Press

- Horner, Avril & Sue Zlosnik (2005). Gothic and the Comic Turn. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Horner, Avril (2002). European Gothic: A Spirited Exchange 1760–1960, Manchester & New York: Manchester University Press

- Hughes, William, Historical Dictionary of Gothic Literature. Scarecrow Press, 2012

- Jackson, Rosemary (1981). Fantasy: The Literature of Subversion.

- Kilgour, Maggie, (1995). The Rise of the Gothic Novel. London: Routledge.

- Jürgen Klein, (1975), Der Gotische Roman und die Ästhetik des Bösen, Darmstadt: Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft.

- Jürgen Klein, Gunda Kuttler (2011), Mathematik des Begehrens", Hamburg: Shoebox House Verlag.

- Korovin, Valentin I. (1988). Fantasticheskii mir russkoi romanticheskoi povesti.

- Medina, Antoinette, (2007). A Vampires Vedas.

- Mighall, Robert, (2003), A Geography of Victorian Gothic Fiction: Mapping History's Nightmares. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Mighall, Robert, (2007), "Gothic Cities", in C. Spooner and E. McEvoy, eds, The Routledge Companion to Gothic. London: Routledge, pp. 54–72.

- O'Connell, Lisa (2010). The Theo-political Origins of the English Marriage Plot, Novel: A Forum on Fiction. Vol. 43, Issue 1, pp. 31–37.

- Peterson, Dale, The Slavic and East European Journal, Vol. 31, No. 1 (Spring, 1987), pp. 36–49

- Punter, David, (1996), The Literature of Terror. London: Longman. (2 vols).

- Punter, David, (2004), The Gothic, London: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Sabor, Peter & Paul Yachnin (2008). Shakespeare and the Eighteenth Century. Ashgate Publishing Ltd.

- Salter, David (2009). This demon in the garb of a monk: Shakespeare, the Gothic and the discourse of anti-Catholicism. Vol. 5, Issue 1, pp. 52–67.

- Sedgwick, Eve Kosofsky (1986). The Coherence of Gothic Conventions. NY: Methuen.

- Shakespeare, William (1997). The Riverside Shakespeare: Second Edition. Boston, NY: Houghton Mifflin Co.

- Simpson, Mark S. (1986) The Russian Gothic Novel and its British Antecedents, Slavica Publishers

- Skarda, Patricia L., and Jaffe, Norma Crow (1981) Evil Image: Two Centuries of Gothic Short Fiction and Poetry. New York: Meridian.

- Skarda, Patricia, (1986) "Gothic Parodies" in Jack Sullivan ed. (1986) The Penguin Encyclopedia of Horror and the Supernatural: 178-9.

- Skarda, Patricia, (1986b) "Oates, Joyce Carol" in Jack Sullivan ed. (1986) The Penguin Encyclopedia of Horror and the Supernatural: 303-4.

- Stevens, David (2000). The Gothic Tradition. ISBN 0-521-77732-1

- Sullivan, Jack, ed. (1986). The Penguin Encyclopedia of Horror and the Supernatural.

- Summers, Montague (1938). The Gothic Quest.

- Townshend, Dale (2007). The Orders of Gothic.

- Varma, Devendra (1957). The Gothic Flame.

- Varma, Devendra, (1986) "Maturin, Charles Robert" in Jack Sullivan (ed) The Penguin Encyclopedia of Horror and the Supernatural: 285-6.

- Wisker, Gina (2005). Horror Fiction: An Introduction. Continuum: New York.

- Wright, Angela (2007). Gothic Fiction. Basingstoke: Palgrave.

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Gothic Fiction at the British Library

- Key motifs in Gothic Fiction – a British Library film

- Gothic Fiction Bookshelf at Project Gutenberg

- Irish Journal of Gothic and Horror Studies

- Gothic Author Biographies

- The Gothic Imagination