Garry Lake

| Garry Lake Hanningajuq | |

|---|---|

| |

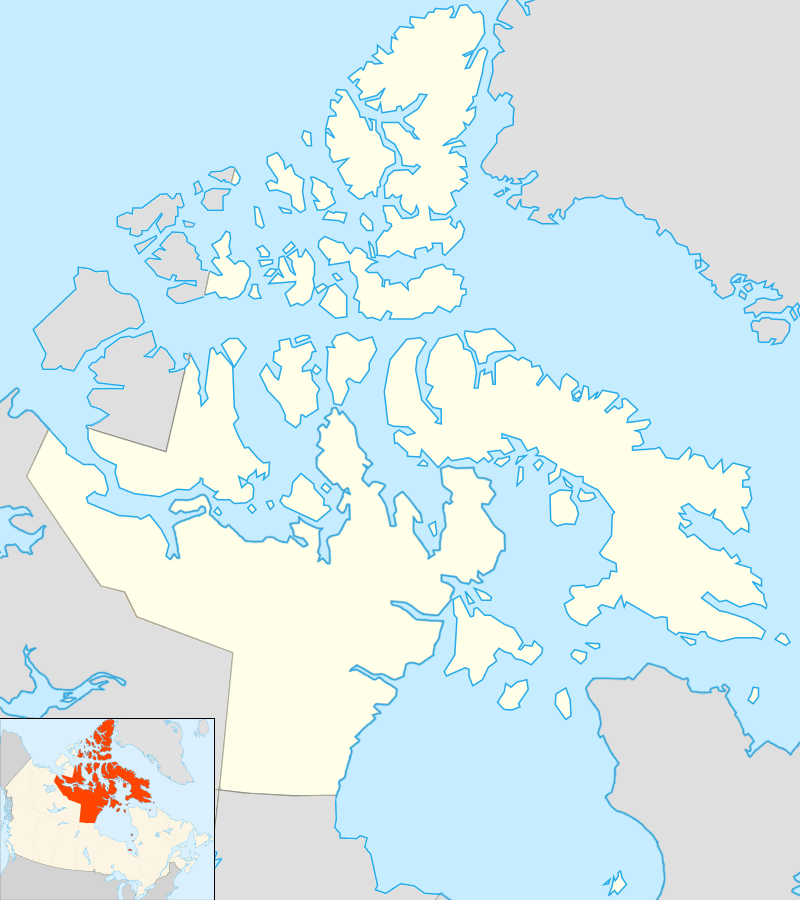

Location in Nunavut | |

| Location | Kivalliq Region, Nunavut |

| Coordinates | 65°53′N 99°51′W / 65.883°N 99.850°WCoordinates: 65°53′N 99°51′W / 65.883°N 99.850°W |

| Primary inflows | Lake Pelly |

| Primary outflows | Back River |

| Basin countries | Canada |

| Max. length | 97 km (60 mi) |

| Max. width | 61 km (38 mi) |

| Surface area | 976 km2 (377 sq mi) |

| Average depth | 6.1 m (20 ft) |

| Max. depth | 9.1 m (30 ft) |

| Surface elevation | 148 m (486 ft) |

| Islands | many |

| Settlements |

uninhabited [1] |

Garry Lake (variant: Garry Lakes; Inuktitut: Hanningajuq, meaning "sideways", or "crooked") is a lake in sub-Arctic Kivalliq Region, Nunavut, Canada. As a portion of the Back River waterway, Garry Lake originates directly east of Lake Pelly and drains to the east by the Back River. A set of rapids separate Buliard Lake (directly to the north) from Garry Lake. Two other sets of rapids separate Garry Lake's three sections (Upper Garry Lake, Garry Lake, Lower Garry Lake) which are also differentiated by elevation.[2][3][4] Garry Lakes are isolated from nearby communities.

Geography

Garry Lakes are a part of the Churchill craton—Rae craton geological province.[3] It is a low relief area including sedge/grass meadows along lake shores, and substrates of glacial silts, sands, and gravels.

Fauna

As moulting Canada geese arrive in late summer, the Canadian Wildlife Service designated the area as a Key Migratory Bird Terrestrial Habitat site.[5]

Ethnography

Hanningajuq is the Inuktitut word for both Garry Lake and the Christian cross.[4] Garry Lake was historically home to Inuit who refer to themselves as Hanningajurmiut or Hanningaruqmiut or Hanningajulinmiut {meaning "the people of the place that lies across"}. Inuit to the north (the Utkusiksalinmiut) refer to Garry Lake Inuit as Ualininmiut ("people from the area of which the sun follows east to west"). The Garry Lake Inuktitut dialect is related to Utkuhiksalik, the dialect of the Utkusiksalinmiut. Like other Caribou Inuit, Hanningajurmiut life consisted of tracking Arctic game (Beverly herd Barren-ground caribou)[6] and fishing (whitefish and lake trout).[7] They lived in igloos in the winter months, and caribou skin tents in the summer months.

Between 1948-1955, Hanningajurmiut were able to trade at Kitikmeot fur trader Stephen Angulalik's outpost located at Atanikittuq ("little connection") at Sherman Inlet.[8] A Roman Catholic mission post was established on an island in Garry Lake in 1949, staffed by Father Joseph Buliard, who disappeared in 1956. The cabin still stands in present day.[9][10] Suffering from famine in 1958 as the annual caribou migration bypassed their territorial hunting grounds, 58 Garry Lake inhabitants died. The federal government intervened by relocating the 31 survivors to Baker Lake. Most Hanningajurmiut never returned to Garry Lake on a permanent basis.[4][11][12][13][14][15]

William Noah, Community Liaison Officer for Areva Resources Canada in Nunavut toured around Garry Lake on August 11, 2009 along with Paul Atuutuva, Betsy Aksawnee, Silas Kenalugak, and David Aksawnee. The pilot was with Forest Helicopters, working on contract for Kiggavik camp for Areva Resources Uranium Camp, 80 km (50 mi) west of Baker Lake. They found a bag and some small items that were still fresh in the attic of the old Buliard mission.

Minerals

In 1981, Kidd Creek Minerals discovered 19 uraniferous boulders in a train formation, extending approximately 1.5 km (0.93 mi) along Garry Lake's north shore. In 2007, Uravan Minerals Inc. surveyed Garry Lake's uranium-rich area and made plans for a multi-phased drill program/exploration project for 2008.[16][17]

See also

References

- ↑ "Principal lakes, elevation and area, by province and territory". Statistics Canada. 2005-02-02. Retrieved 2015-03-11.

- ↑ "Garry, Lake". bartleby.com. Retrieved 2008-03-09.

- 1 2 3 "Tuhaalruuqtut Ancestral Sounds". Inuit Heritage Centre. 2005. Retrieved 2008-03-10.

- ↑ "Middle Back River Southern Nunavut". bsc.eoc.org. Retrieved 2008-03-14.

- ↑ Duquette, L. (1985). "Beverly and Kaminuriak caribou monitoring and land use controls": 38. Archived from the original on November 17, 2004. Retrieved 2008-03-14.

- ↑ Fisher, H.D. (1957). "Arctic investigations by the Fisheries Research Board of Canada, 1956-57". Arctic. 10 (4): 244–245. doi:10.14430/arctic3769. Retrieved 2008-03-14.

- ↑ "Sherman Inlet". Kitikmeot Heritage Society. Retrieved 2008-03-13.

- ↑ (Tester, 1994, p.240)

- ↑ Pick, A. (November 2007). "Paddling Back in Time". The Arctic. Retrieved 2008-03-10.

- ↑ Tester, F.J.; Kulchyski, P. (1994-01-01). Tammarniit (Mistakes), Inuit Relocation in the Eastern Arctic, 1939-63. ubcpress.ca. ISBN 978-0-7748-0452-3. Retrieved 2008-03-09.

- ↑ "Hannah Kigusiuq". spiritwrestler.com. Retrieved 2008-03-09.

- ↑ Dyck, C.J.; Briggs, J.L. (2004-05-16). "Historical developments in Utkuhiksalik phonology" (PDF). utoronto.ca. Retrieved 2008-03-09.

- ↑ "Baker Lake, Nunavut". edu.nu.ca. Retrieved 2008-03-09.

- ↑ Hamilton, J.D. (1994). Arctic revolution : social change in the Northwest Territories, 1935-1994. Toronto: Dundurn Press. p. 67. ISBN 1-55002-206-7. Retrieved 2008-03-10.

- ↑ "Update-Garry Lake Uranium Property" (PDF). uravanminerals.com. 2007-11-28. Retrieved 2008-03-09.

- ↑ "Uravan Minerals Inc. Update - Garry Lake Uranium Property". Calgary: CNW Group. 2007-11-28. Retrieved 2008-03-10.