Fort Anne

View of Annapolis Basin from Fort Anne | |

| Established | 1629 |

|---|---|

| Location | Annapolis Royal, Nova Scotia, Canada |

| Website | |

| Official name | Fort Anne National Historic Site of Canada |

| Designated | 1920 |

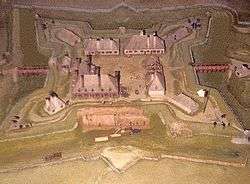

Fort Anne is a four-star fort built to protect the harbour of Annapolis Royal, Nova Scotia. The fort repelled all French attacks during the early stages of King George's War.

Now designated a National Historic Site of Canada, it is managed by Parks Canada. The 1797 officer's quarters was renovated in the 1930s and now house the museum with exhibits about the fort's history and historic artifacts from the area.

A 1/2 km trail runs along the fort's earthen walls, and provides a view of the Annapolis River and basin.

History

The site has been fortified since 1629, when the Scots came to colonize Nova Scotia (New Scotland) and built Charles Fort. The region was reverted to French control in the 1630s and Charles de Menou d'Aulnay began work on the first of four forts on the same site, then known as Port Royal. In 1702, the French began construction of the current Vauban earthwork that is found there today.

Queen Anne's War

During Queen Anne's War, the fort fell to British and New England troops after a week-long siege in 1710 which marked the British conquest of Acadia. A British governor and garrison replaced the French at the fort renaming the Port Royal settlement Annapolis Royal after Queen Anne. With the Treaty of Utrecht three years later, the British gained full control of mainland Nova Scotia and kept Annapolis Royal as the capital until the founding of Halifax in 1749. The 40th Regiment of Foot was raised at Fort Anne in 1717.

Father Rale's War

Blockade of Annapolis Royal (1722)

During Father Rale's War,[1] in July 1722 the Abenaki and Mi'kmaq attempted to create a blockade of Annapolis Royal, with the intent of starving the capital. The natives captured 18 fishing vessels and prisoners from present-day Yarmouth to Canso. They also seized prisoners and vessels from the Bay of Fundy.

In response to the New England attack on Father Rale at Norridgewock in March 1722, 165 Mi'kmaq and Maliseet troops gathered at Minas to lay siege to the Lt. Governor of Nova Scotia at Annapolis Royal.[2] Under potential siege, in May 1722, Lieutenant Governor John Doucett took 22 Mi'kmaq hostage at Annapolis Royal to prevent the capital from being attacked.[3] Massachusetts Governor Samuel Shute declared war on the Abenaki.

New Englanders retrieved some of the vessels and prisoners after the Battle at Winnepang (Jeddore Harbour) in which thirty-five natives and five New-Englanders were killed. Other vessels and prisoners were retrieved at Malagash Harbour after a ransom was paid.[4]

Raid on Annapolis Royal (1724)

During Father Rale's War, the worst moment of the war for the capital came in early July 1724 when a group of sixty Mikmaq and Maliseets raided Annapolis Royal. They killed and scalped a sergeant and a private, wounded four more soldiers, and terrorized the village. They also burned houses and took prisoners.[5] The British responded on July 8 by executing one of the Mi'kmaq hostages on the same spot the sergeant was killed. They also burned three Acadian houses in retaliation.[6]

As a result of the raid, three blockhouses were built to protect the town. The Acadian church was moved closer to the fort so that it could be more easily monitored.[7]

King George's War

During King George's War, the French launched three expeditions against the capital to regain the fort with no success, the most famous being the Duc d'Anville Expedition.

Father Le Loutre's War

During Father Le Loutre's War, the capital of Acadia was moved from Annapolis Royal to Halifax. Fort Edward, Fort Lawrence and Fort Anne were all supplied by and dependent on the arrival of Captains Cobb, Rogers or Taggart, in one of the government sloops. These vessels took the annual or semi-annual relief to their destination. They carried the officers and their families to and fro, as required.[8]

On 15 August 1752, commander John Handfield, Esq., widower, married Miss Mary Handfield. (Handfield's first wife was Acadian.)

French and Indian War

During the French and Indian War, the British engaged in the Bay of Fundy Campaign (1755) and deported the Acadians living in the area. With the fall of Quebec in 1759, the fort no longer held the same military importance.

It was however still used as an outpost during the American Revolution, where the 84th Regiment of Foot (Royal Highland Emigrants) was stationed, and the War of 1812 in defence of the town from American privateers.

The fort acquired the name Fort Anne in the 19th century.

Commanding Officers

- John Doucett (1717-1726)

- Lawrence Armstrong

- Alexander Cosby

- Paul Mascarene

- Henry Daniel (military officer)

- John Handfield (1752-1755)

Fort Anne National Historic Site

In 1917, Fort Anne was acquired by the Dominion Parks Branch, the predecessor of Parks Canada, and designated the second national historic park, bearing the name Fort Anne National Park (Fort Howe in Saint John, New Brunswick had been the first historical park).[9] Two years later, a new program of National Historic Sites was established in 1919 to replace the incipient system of historic parks, and Fort Anne was designated a National Historic Site in 1920.[10]

Although Fort Anne was neither the first National Historic Park (Fort Howe was designated three years earlier), nor was it the first site designated under the replacement National Historic Site program, it is nonetheless sometimes referred to as Canada's "first national historic site" or the "first administered national historic site", because it was the first site acquired by the federal government for national historic purposes that has subsequently remained under Parks Canada administration (Fort Howe was eventually conveyed to the municipality).[11]

Legacy

On 28 June 1985 Canada Post issued 'Fort Anne, N.S., circa 1763.' one of the 20 stamps in the “Forts Across Canada Series” (1983 & 1985). The stamps are perforated 12½ x 13 and were printed by Ashton-Potter Limited based on the designs by Rolf P. Harder.[12]

See also

References

- ↑ The Nova Scotia theatre of the Drummer War is named the "Mi'kmaq-Maliseet War" by John Grenier. The Far Reaches of Empire: War in Nova Scotia 1710-1760 University of Oklahoma Press. 2008.

- ↑ John Grenier. First Way of War. 2003. p. 47; Grenier. 2008, p. 56

- ↑ Grenier, p. 56

- ↑ Murdoch, Beamish A history of Nova-Scotia, or Acadie. Volume 1, p. 399.

- ↑ Faragher, John Mack, A Great and Noble Scheme New York; W. W. Norton & Company, 2005. pp. 164-165.; Beamish Murdoch. A History of Nova Scotia or Acadie. Vol. 1. pp. 408-409

- ↑ Brenda Dunn, p. 123

- ↑ Brenda Dunn, pp. 124-125

- ↑ Beamish Murdoch. a History of Nova Scotia Vol 2, p. 232.

- ↑ Taylor, C.J. (1990). Negotiating the Past: The Making of Canada's National Historic Parks and Sites. Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen's University Press. 28-9. ISBN 0-7735-0713-2.

- ↑ Fort Anne National Historic Site of Canada. Canadian Register of Historic Places. Retrieved 30 September 2012.

- ↑ "Canada's Oldest National Historic Site". Fort Anne National Historic Site of Canada. Parks Canada. Retrieved 30 September 2012.

- ↑ http://data4.collectionscanada.ca/netacgi/nph-brs?s1=1008&l=20&d=POST&p=1&u=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.collectionscanada.ca%2Farchivianet%2F020117%2F020117030306_e.html&r=1&f=G&SECT3=POST Canada Post issued 'Fort Anne, N.S., circa 1763.'

Further reading

- Brenda Dunn, A History of Port Royal/Annapolis Royal: 1605-1800, Halifax: Nimbus, 2004

- Parks Canada, Fort Anne National Historic Site brochure, undated (2001 ?).

External links

- Parks Canada - Fort Anne National Historic Site of Canada

- Fort Anne Bronze Cannon

- Canadian Encyclopedia entry

Coordinates: 44°44′28.05″N 65°31′7.88″W / 44.7411250°N 65.5188556°W