Sangharakshita

| Sangharakshita | |

|---|---|

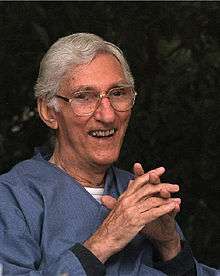

At the Western Buddhist Order men's ordination course, Guhyaloka, Spain, June 2002 | |

| Religion | Buddhism |

| Dharma names | Urgyen Sangharakshita |

| Personal | |

| Nationality | British |

| Born |

August 26, 1925 Tooting, London, England, United Kingdom |

| Senior posting | |

| Based in | Coddington, England, United Kingdom |

| Religious career | |

| Website | www.sangharakshita.org |

Sangharakshita (born August 26, 1925 as Dennis Philip Edward Lingwood) is a Buddhist teacher and writer, and founder of the Triratna Buddhist Community, which was known until 2010 as the Friends of the Western Buddhist Order, or FWBO.[1][2]

He was one of a handful of westerners to be ordained as Theravadin Bhikkhus in the period following World War II,[3] and spent over 20 years in Asia,[4] where he had a number of Tibetan Buddhist teachers.[5] In India, he was active in the conversion movement of Dalits—so-called "Untouchables"—initiated in 1956 by B. R. Ambedkar.[4] He has authored more than 60 books, including compilations of his talks, and has been described as "one of the most prolific and influential Buddhists of our era,"[6] "a skilled innovator in his efforts to translate Buddhism to the West,"[7] and as "the founding father of Western Buddhism"[8] for his role in setting up what is now the Triratna Buddhist Community,[9] but has also been criticised for having had sexual relations with Order members.[10]

Sangharakshita formally retired in 1995 and in 2000 stepped down from the movement's leadership, but he remains its dominant figure, and lives at its headquarters in Coddington, England.[11] Sangharakshita has often been regarded as a controversial teacher.[3]

Early life

Sangharakshita was born Dennis Philip Edward Lingwood in Stockwell, London, in 1925.[12] After being diagnosed with a heart condition he spent much of his childhood confined to bed, and used the opportunity to read widely.[13] His first encounter with non-Christian thought was with Madame Helena Blavatsky's Isis Unveiled,[14] upon reading which, he later said, he realised that he had never been a Christian.[15] The following year he came across two Buddhist texts—the Diamond Sutra and the Platform Sutra—and concluded that he had always been a Buddhist.[15]

As Dennis Lingwood, he joined the Buddhist Society at the age of 18,[16] and formally became a Buddhist in May 1944 by taking the Three Refuges and Five Precepts from the Burmese monk, U Thittila.[13]

He was conscripted into the army in 1943, and served in India, Sri Lanka (then known as Ceylon), and Singapore as a radio engineer[17] in the Royal Corps of Signals.[18] It was in Sri Lanka, while in contact with the swamis in the (Hindu) Ramakrishna Mission, that he developed the desire to become a monk.[19] In 1946, after the cessation of hostilities, he was transferred to Singapore, where he made contact with Buddhists and learned to meditate.[20]

India

Having been conscripted into the Army and posted to India, at the end of the war Sangharakshita handed in his rifle, left the camp where he was stationed and deserted.[20] He moved about in India for a few years,with a Bengali novice Buddhist, the future Buddharakshita, as his companion, meditating and experiencing for himself the company of eminent spiritual personalities of the times, like Mata Anandamayi, Ramana Maharishi and Swamis of Ramakrishna Mission. They spent fifteen months in 1947-48, in the Ramakrishna Mission centre at Muvattupuzha with the consent of Swami Tapasyananda and Swami Agamananda. In May 1949 he became a novice monk, or sramanera, in a ceremony conducted by the Burmese monk, U Chandramani, who was then the most senior monk in India. It was then that he was given the name Sangharakshita (Pali: Sangharakkhita), which means "protected by the spiritual community."[20] Sangharakshita took full bhikkhu ordination the following year,[18] with another Burmese bhikkhu, U Kawinda, as his preceptor (upādhyāya), and with the Ven. Jagdish Kashyap as his teacher (ācārya).[20] He studied Pali, Abhidhamma, and Logic with Jagdish Kashyap at Benares (Varanasi) University.[16] In 1950, at Kashyap's suggestion, Sangharakshita moved to the hill town of Kalimpong[14] close to the borders of India, Bhutan, Nepal. and Sikkim, and only a few miles from Tibet. Kalimpong was his base for 14 years until his return to England in 1966.[17]

During his time in Kalimpong, Sangharakshita formed a young men's Buddhist association and established an ecumenical centre for the practice of Buddhism (the Triyana Vardhana Vihara).[17] He also edited the Maha Bodhi Journal and established a magazine, Stepping Stones.[21] In 1951, Sangharakshita met the German-born Lama Govinda, who was the first Buddhist Sangharakshita had known "to declare openly the compatibility of art with the spiritual life", and who gave Sangharakshita a greater appreciation for Tibetan Buddhism.[22] Govinda had begun his explorations of Buddhism in the Theravada tradition, studying briefly under the German-born bhikkhu, Nyanatiloka Mahathera (who gave him the name Govinda), but after meeting the Gelug Lama, Tomo Geshe Rinpoche, in 1931, he turned towards Tibetan Buddhism.[23] Sangharakshita's spiritual explorations were to follow a similar trajectory.

Sangharakshita was ordained in the Theravada school, but said he became disillusioned by what he felt was the dogmatism, formalism, and nationalism of many of the Theravadin bhikkhus he met[5] and became increasingly influenced by Tibetan Buddhist teachers who had fled Tibet after the Chinese invasion in the 1950s. Two years after his meeting with Lama Govinda he began studying with the Gelug Lama, Dhardo Rinpoche.[5] Sangharakshita also received initiations and teachings from teachers who included Jamyang Khyentse, Dudjom Rinpoche, as well as Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche.[5] It was Dhardo Rinpoche who was to give Sangharakshita Mayahana ordination.[16] Later, Sangharakshita also studied with a Ch'an teacher, Yogi Chen (Chen Chien-Ming), along with another English monk, Bhikkhu Khantipalo.[24] Together, the three men turned their ongoing seminar on Buddhist theory and practice into a book, Buddhist Meditation, Systematic and Practical.[25]

In 1952, Sangharakshita met Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar[26] (1891–1956), the chief architect of the Indian constitution and India's first law minister. Ambedkar, who had been a so-called Untouchable, converted to Buddhism, along with 380,000 other Untouchables (now known as "dalits") on 14 October 1956.[27] Ambedkar and Sangharakshita had been in correspondence since 1950, and the Indian politician had encouraged the young monk to expand his Buddhist activities.[28] Ambedkar appreciated Sangharakshita's "commitment to a more critically engaged Buddhism that did not at the same time dilute the cardinal precepts of Buddhist thought".[29] Ambedkar initially invited Sangharakshita to perform his conversion ceremony, but the latter refused, arguing that U Chandramani should preside.[29] Ambedkar died six weeks later, leaving his conversion movement leaderless, and Sangharakshita, who had just arrived in Nagpur to visit dalit Buddhists,[29] continued what he felt was Ambedkar's work by lecturing to former Untouchables,[26] and presiding over a ceremony in which a further 200,000 Untouchables converted.[27] For the next decade, Sangharakshita spent much of his time visiting dalit Buddhist communities in western India.[30]

Return to the West

In 1964, Sangharakshita was invited to help with a dispute at the Hampstead Buddhist Vihara in north London,[31] where he proved to be a popular teacher.[12] His ecumenical approach and failure to conform to some of the trustees' expectations was said to contrast with the strict Theravadin-style Buddhism at the vihara.[12] Although originally planning to stay only six months, he decided to settle in England, but after he returned to India for a farewell tour, the Vihara's trustees voted to expel him.[12]

Sangharakshita returned to England and in April 1967 founded the Friends of the Western Buddhist Order.[12] The Western Buddhist Order was founded a year later, when he ordained the first dozen men and women. The first ordinations were attended by a Zen monk, a Shin priest, and two Theravadin monks.[32]

Satisfied neither with the lay-Buddhist approach of the Buddhist Society, nor the monastic approach of the Hampstead vihara—the two dominant Buddhist organisations in Britain at that time—he created what he said was a new form of Buddhism. The order would be neither lay nor monastic,[33] and members take a set of ten precepts[32] that are a traditional part of Mahayana Buddhism.[34]

Initially, Sangharakshita led all classes and conducted all ordinations.[32] He gave lectures drawing on what he felt were the essential teachings of all the major Buddhist schools.[31] He led major retreats twice a year and frequent day and weekend events.[31] As the order grew, and centres became established across Britain and in other countries, order members took more responsibility until, in August 2000, he devolved his responsibilities as the head of the Western Buddhist Order to eight men and women who formed what was called the "College of Public Preceptors."[35]

Sexual misconduct

In 1997, Sangharakshita became the focus for controversy when The Guardian newspaper published complaints concerning some of his sexual relationships with FWBO members during the 1970s and 1980s.[36] For a decade following these public revelations, he declined to give any response to concerns from within the movement that he had misused his position as a Buddhist teacher to sexually exploit young men. He later addressed the controversy, stressing that his sexual partners were, or appeared to be, willing, and expressed regret for any mistakes.[37]

Contributions and legacy

Sangharakshita has been described as "among the first Westerners who devoted their life to the practice as well as the spreading of Buddhism," and as a "prolific writer, translator, and practitioner of Buddhism."[38] As a Westerner seeking to use Western concepts to communicate Buddhism, he has been compared to Teilhard de Chardin,[39] termed "the founding father of Western Buddhism,"[8] and noted as "a skilled innovator in his efforts to translate Buddhism to the West."[7]

For Sangharakshita, as with other Buddhists, the factor that unites all Buddhist schools is not any particular teaching, but the act of "going for refuge" (sarana-gamana), which he regards "not simply as a formula but as a life-changing event"[14] and as an ongoing "reorientation of one's life away from mundane concerns to the values embodied in the Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha."[40] Any decisive act upon the spiritual path—renunciation, ordination, initiation, the attainment of Stream Entry, and the arising of the bodhicitta—are manifestations or examples of Going for Refuge.[41]

Among his distinctive views is his use of the scientific theory of evolution as a metaphor for spiritual development, referring to biological evolution as the "lower evolution" and spiritual development as being a form of self-directed "higher evolution". Though he considers women and men equally capable of Enlightenment and ordained them equally right from the start, he has also said he had "tentatively reached the conclusion that the spiritual life is more difficult for women because they are less able than men to envisage...something purely transcendental..."[42] He also criticised heterosexual nuclear relationships as tending to neuroticism. The FWBO has been accused of cult-like behaviour in the 1970s and 80s for encouraging heterosexual men to engage in sexual relationships with men in order to get over their fear of intimacy with men and obtain spiritual growth.[41] He has drawn parallels between Buddhism and the spirit of the Romantics, who believed that what art reveals has great moral and spiritual significance, and has written of "the religion of art."[43]

Including compilations of his talks, Sangharakshita has authored more than 60 books. Meanwhile, the Triratna Buddhist Community, which he founded as the FWBO, has been described as "perhaps the most successful attempt to create an ecumenical international Buddhist organization".[44] The community is one of the three largest Buddhist movements in Britain,[45] and has a presence in Europe, the Americas, Asia, and Africa. More than a fifth of all Western Buddhist Order members, as of 2006, were in India,[46] where Dr. Ambedkar's mission to convert dalits to Buddhism continues.[47] Martin Baumann, a scholar of Buddhism, has estimated that there are 100,000 people worldwide who are affiliated with the Triratna Buddhist Community.[47]

For Buddhologist Francis Brassard, Sangharakshita's major contribution is "without doubt his attempt to translate the ideas and practices of [Buddhism] into Western languages."[48] The non-denominational nature of the Triratna Buddhist Community,[32] its equal ordination for both men and women,[49] and its evolution of new forms of shared practice, such as what it calls team-based right livelihood projects, have been cited as examples of such "translation", and also as the creation of a "Buddhist society in miniature within the Western, industrialized world".[4] For Martin Baumann, the Triratna Buddhist Community serves as proof that "Western concepts, such as a capitalistic work ethos, ecological considerations, and a social-reformist perspective, can be integrated into the Buddhist tradition".[50]

Bibliography

Biography

- Anagarika Dharmapala: A Biographical Sketch

- Great Buddhists of the Twentieth Century

Books on Buddhism

- The Eternal Legacy: An Introduction to the Canonical Literature of Buddhism

- A Survey of Buddhism: Its Doctrines and Methods Through the Ages

- The Ten Pillars of Buddhism

- The Three Jewels: The Central Ideals of Buddhism

Edited seminars and lectures on Buddhism

- The Bodhisattva Ideal

- Buddha Mind

- The Buddha's Victory

- Buddhism for Today – and Tomorrow

- Creative Symbols of Tantric Buddhism

- The Drama of Cosmic Enlightenment

- The Essence of Zen

- A Guide to the Buddhist Path

- Human Enlightenment

- The Inconceivable Emancipation

- Know Your Mind

- Living with Awareness

- Living with Kindness

- The Meaning of Conversion in Buddhism

- New Currents in Western Buddhism

- Ritual and Devotion in Buddhism

- The Taste of Freedom

- The Yogi's Joy: Songs of Milarepa

- Tibetan Buddhism: An Introduction

- Transforming Self and World

- Vision and Transformation

- Who Is the Buddha?

- What Is the Dharma?

- What Is the Sangha?

- Wisdom Beyond Words

Essays and papers

- Alternative Traditions

- Crossing the Stream

- Going For Refuge

- The Priceless Jewel

- Aspects of Buddhist Morality

- Dialogue between Buddhism and Christianity

- The Journey to Il Covento

- St Jerome Revisited

- Buddhism and Blasphemy

- Buddhism, World Peace, and Nuclear War

- The Bodhisattva Principle

- The Glory of the Literary World

- A Note on The Burial of Count Orgaz

- Criticism East and West

- Dharmapala: The Spiritual Dimension

- With Allen Ginsburg In Kalimpong (1962)

- Indian Buddhists

- Ambedkar and Buddhism

Memoirs, autobiography and letters

- Facing Mount Kanchenjunga: An English Buddhist in the Eastern Himalayas

- From Genesis to the Diamond Sutra: A Western Buddhist's Encounters with Christianity

- In the Sign of the Golden Wheel: Indian Memoirs of an English Buddhist

- Moving Against the Stream: The Birth of a New Buddhist Movement

- The Rainbow Road: From Tooting Broadway to Kalimpong

- The History of My Going for Refuge

- Precious Teachers

- Travel Letters

- Through Buddhist Eyes

Poetry and art

- The Call of the Forest and Other Poems

- Complete Poems 1941–1994

- Conquering New Worlds: Selected Poems

- Hercules and the Birds

- In the Realm of the Lotus

- The Religion of Art

Polemic

- Forty Three Years Ago: Reflections on My Bhikkhu Ordination

- The FWBO and 'Protestant Buddhism': An Affirmation and a Protest

- The Meaning of Orthodoxy in Buddhism

- Was the Buddha a Bhikkhu? A Rejoinder to a Reply to 'Forty Three Years Ago'.

Translation

- The Dhammapada

See also

- Dharmachari Subhuti - Senior associate of Sangharakshita

References

- ↑ Batchelor, Stephen (1994), The Awakening of the West: The Encounter of Buddhism and Western Culture, Parallax Press, p. 333, ISBN 0-938077-69-4

- ↑ George D. Chryssides; Margaret Z. Wilkins (2006). A Reader in New Religious Movements: Readings in the Study of New Religious. London: Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 0826461670.

- 1 2 Batchelor, Stephen (1994), The Awakening of the West: The Encounter of Buddhism and Western Culture, Parallax Press, p. 326, ISBN 0-938077-69-4

- 1 2 3 Baumann, Martin (May 1998), "Working in the Right Spirit: The Application of Buddhist Right Livelihood in the Friends of the Western Buddhist Order" (PDF), Journal of Buddhist Ethics, 5: 132.

- 1 2 3 4 Batchelor, Stephen (1994), The Awakening of the West: The Encounter of Buddhism and Western Culture, Parallax Press, p. 329, ISBN 0-938077-69-4

- ↑ Smith, Huston; Novak, Philip (2004), Buddhism: A Concise Introduction, HarperCollins, p. 221, ISBN 0-06-073067-6

- 1 2 Doyle, Anita (Summer 1996), "Women, Men, and Angels (review)", Tricycle: The Buddhist Review, 5: 105

- 1 2 Berkwitz, Stephen C (2006), Buddhism in world cultures: comparative perspectives, ABC-CLIO, p. 303, ISBN 1-85109-782-1

- ↑ Kay, David N (2004), Tibetan and Zen Buddhism in Britain: transplantation, development and adaptation, Routledge, p. 25, ISBN 0-415-29765-6

- ↑ Tsomo, Karma Lekshe (2000), Innovative Buddhist women: swimming against the stream, Routledge, p. 266, ISBN 0-7007-1253-4

- ↑ "Adhisthana". Triratna Buddhist Order. Retrieved 19 February 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Chryssides, George D.; Wilkins, Margaret Z. (2006), A Reader in New Religious Movements, Continuum International Publishing Group, p. 46, ISBN 0-8264-6168-9

- 1 2 Chryssides, George D.; Wilkins, Margaret Z. (2006), A Reader in New Religious Movements, Continuum International Publishing Group, p. 47, ISBN 0-8264-6168-9

- 1 2 3 Lopez Jr, Donald S (2002), A Modern Buddhist Bible: Essential Readings from East and West, Beacon Press, p. 186, ISBN 0-8070-1243-2

- 1 2 Batchelor, Stephen (1994), The Awakening of the West: The Encounter of Buddhism and Western Culture, Parallax Press, p. 323, ISBN 0-938077-69-4

- 1 2 3 Snelling, John (1999), The Buddhist Handbook: A Complete Guide to Buddhist Schools, Teaching, Practice, and History, Inner Traditions, p. 230, ISBN 0-89281-761-5

- 1 2 3 Chryssides, George D. (1999), Exploring New Religions, Continuum International Publishing Group, p. 225, ISBN 0-8264-5959-5

- 1 2 Prebish, Charles S. (1999), Luminous passage: the practice and study of Buddhism in America, University of California Press, p. 47, ISBN 0-520-21697-0

- ↑ Chryssides, George D.; Wilkins, Margaret Z. (2006), A Reader in New Religious Movements, Continuum International Publishing Group, pp. 47–48, ISBN 0-8264-6168-9

- 1 2 3 4 Chryssides, George D.; Wilkins, Margaret Z. (2006), A Reader in New Religious Movements, Continuum International Publishing Group, p. 48, ISBN 0-8264-6168-9

- ↑ Oldmeadow, Harry (1999), Journeys East: 20th century Western encounters with Eastern religious traditions, Continuum International Publishing Group, p. 280, ISBN 0-8264-5959-5

- ↑ Batchelor, Stephen (1994), The Awakening of the West: The Encounter of Buddhism and Western Culture, Parallax Press, pp. 328–329, ISBN 0-938077-69-4

- ↑ Lopez, Donald (2002), A Modern Buddhist Bible: Essential Readings from East and West, Beacon Press, p. 98, ISBN 978-0-8070-1243-7

- ↑ Khantipalo, Laurence (2002), Noble Friendship: Travels of a Buddhist Monk, Windhorse Publications, pp. 140–142, ISBN 1-899579-46-X

- ↑ Chen, C.M. (1983), Buddhist Meditation, Systematic and Practical (Volume 42 of Hsientai fohsüeh tahsi), Mile ch'upanshe, p. xiii

- 1 2 Batchelor, Stephen (1994), The Awakening of the West: The Encounter of Buddhism and Western Culture, Parallax Press, p. 331, ISBN 0-938077-69-4

- 1 2 Chryssides, George D. (1999), Exploring New Religions, Continuum International Publishing Group, p. 226, ISBN 0-8264-5959-5

- ↑ Ganguly, debjani (2005), Caste, Colonialism, and Counter-Modernity: Notes on a Postcolonial Hermeneutics of Caste, Routledge, pp. 167–168, ISBN 0-415-34294-5

- 1 2 3 Ganguly, debjani (2005), Caste, Colonialism, and Counter-Modernity: Notes on a Postcolonial Hermeneutics of Caste, Routledge, p. 168, ISBN 0-415-34294-5

- ↑ Ganguly, debjani (2005), Caste, Colonialism, and Counter-Modernity: Notes on a Postcolonial Hermeneutics of Caste, Routledge, p. 169, ISBN 0-415-34294-5

- 1 2 3 Chryssides, George D.; Wilkins, Margaret Z. (2006), A Reader in New Religious Movements, Continuum International Publishing Group, p. 49, ISBN 0-8264-6168-9

- 1 2 3 4 Rawlinson, Andrew (1997), The Book of Enlightened Masters, Open Court, p. 503, ISBN 0-8126-9310-8

- ↑ Queen, Christopher S.; King, Sallie B. (1996), Engaged Buddhism, SUNY Press, p. 86, ISBN 0-7914-2844-3

- ↑ Keown, Damien (2003), A Dictionary of Buddhism, Oxford University Press US, p. 70, ISBN 0-8126-9310-8

- ↑ "Have Map, Can Unravel". Dharmalife.com. Retrieved 2011-06-23.

- ↑ Tsomo, Karma Lekshe (2000), Innovative Buddhist Women: Swimming Against the Stream, Routledge, pp. 266–267, ISBN 978-0-7007-1219-9

- ↑ Vajragupta (2010), The Triratna Story: Behind the Scenes of a New Buddhist Movement, Windhorse, ISBN 978-1-899579-92-1

- ↑ Brassard, Francis (2000), The Concept of Bodhicitta in Santideva's Bodhicaryavatara, SUNY Press, pp. 22–23, ISBN 978-0-7914-4575-4

- ↑ Brassard, Francis (2000), The Concept of Bodhicitta in Santideva's Bodhicaryavatara, SUNY Press, p. 23, ISBN 0-7914-4575-5

- ↑ Batchelor, Stephen (1994), The Awakening of the West: The Encounter of Buddhism and Western Culture, Parallax Press, p. 334, ISBN 0-938077-69-4

- 1 2 Batchelor, Stephen (1994), The Awakening of the West: The Encounter of Buddhism and Western Culture, Parallax Press, p. 335, ISBN 0-938077-69-4

- ↑ Transforming Self and World, 1995, p117

- ↑ McMahan, David L. (2008), The Making of Buddhist Modernism, Oxford University Press US, p. 334, ISBN 0-19-518327-4

- ↑ Oldmeadow, Harry L. (2004), Journeys East: 20th century Western encounters with Eastern religious traditions, World Wisdom, Inc, p. 280, ISBN 0-941532-57-7

- ↑ Beckerlegge, Gwilym (2001), From Sacred Text to Internet, Ashgate, p. 147, ISBN 978-0-7546-0748-9

- ↑ McAra, Sally (2007), Land of Beautiful Vision: Making a Buddhist Sacred Place in New Zealand, University of Hawaii Press, p. 18, ISBN 978-0-8248-2996-4

- 1 2 King, Sally B. (2005), Being Benevolence: The Social Ethics of Engaged Buddhism, University of Hawaii Press, p. 79, ISBN 978-0-8248-2935-3

- ↑ Brassard, Francis (2000), The Concept of Bodhicitta in Śāntideva's Bodhícaryāvatāra, SUNY Press, pp. 22–23, ISBN 978-0-7914-4575-4

- ↑ McAra, Sally (2007), Land of Beautiful Vision: Making a Buddhist Sacred Place in New Zealand, University of Hawaii Press, p. 60, ISBN 978-0-8248-2996-4

- ↑ Baumann, Martin (May 1998), "Working in the Right Spirit:The Application of Buddhist Right Livelihood in the Friends of the Western Buddhist Order", Journal of Buddhist Ethics, 5: 135.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sangharakshita. |