Golden-cheeked warbler

| Golden-cheeked warbler | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Family: | Parulidae |

| Genus: | Setophaga |

| Species: | S. chrysoparia |

| Binomial name | |

| Setophaga chrysoparia (Sclater & Salvin, 1861) | |

| |

| Range of S. chrysoparia Breeding range Winter range | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Dendroica chrysoparia Sclater & Salvin, 1861 | |

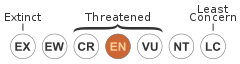

The golden-cheeked warbler (Setophaga chrysoparia [formerly Dendroica chrysoparia]), also known as the gold finch of Texas, is an endangered species of bird that breeds in Central Texas, from Palo Pinto County southwestward along the eastern and southern edge of the Edwards Plateau to Kinney County. The golden-cheeked warbler is the only bird species with a breeding range confined to Texas.

Historical Representation

The golden-cheeked warbler is very staggering because of its bright yellow cheeks that is counterposed by its black throat and back, but it is found more by its unique buzzing song emerging from the wooded canyons where it breeds.[2] Golden-cheeked warblers form in 33 counties in central Texas and are dependent on Ashe Juniper (blueberry juniper or cedar) for their fine bark stripes for nesting reasons.[3]

Habitat

The golden-cheeked warbler (GCWA) are endemic to Texas and no other quarters. Their habitat can range from moist, to dry areas around central and southern Texas. The nesting habitat in the further moist realms can be discovered in tall, closed canopy, compressed, mature stands of Ashe juniper trees along with Texas, shin, live, Lacey, and post oak trees. In the drier spheres of Texas the GCWAs can be found in upland juniper-oak woodlands off of flat topography.[4] They use Ashe juniper bark and spider webs to build their nests. Females lay three to four eggs. When migration and winter hits the habitat stays relatively similar: a variety of short-lived evergreen forests with pines between 3,300 and 8,300 feet.[5]

Behavior

Warblers only nest in Texas, primarily in juniper trees. However, they have also been found to nest in oak trees and cedar elms. During the winter warblers seek warmth in Mexico and Northern Central America.[6]

After winter habitation, adult male warblers beat their population back to central nesting grounds by about 5 days in order to prepare competing for the attention of female warblers. Male warblers win attention of the females through their “chip” sounds which they also make as a warning call during times of possible danger.[7]

Though male warblers are found either singing or searching for food, females carry the responsibility of nest building as well as keeping the eggs incubated. Warblers only nest once per season, laying between three and four eggs each time, which take an average of twelve days to hatch.[8] Female warblers are considered shy and go more unnoticed compared to the always-singing males.[9]

Warblers typically forge through grabbing insects from foliage and branches (forging strategy known as gleaning), and by resting at branch edges until the opportunity to snatch insects that fly past (strategy known as sallying).[10]

Conservation

The breeding range of the warbler ranges to an extent of only about twenty acres, so spaces for habitation are limited.[11] Many spots of warbler habitation have been cleared for the construction of houses, roads, and stores or to grow crops or grass for livestock. Juniper trees, the primary nesting place for warblers, have also been cut down and used for different timber products, especially before the 1940s.[12] Other woodlands were flooded when large lakes were constructed.[13] Sitting at the top of the endangered list (of species in North America) since May 1990, different projects are currently underway to restore the habitat of the Golden-Cheeked warbler. Efforts include The Safe Harbor agreement between Environmental Defense and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, with the goal of rebuilding and creating new, safe habitats for the warbler (along with other endangered species). The Balcones Canyonlands Conservation Plan (BCCP) is another project responsible for building warbler preserves, with the goal of eventually adding a total of 41,000 acres to the warbler's habitat .[14] These initiatives along with many others encourage landowners to learn more about the warbler (along with other species that inhabit their property) so local land owners may provide proper maintenance and protection of the warbler’s habitat.[15] A project that significantly aided habitat restoration for the Warbler includes the U.S. Army’s (Fort Hood base) success in protecting the largest patch of juniper-oak trees.[16]

Population

The most serious problems that are facing the Golden-cheeked warbler today, as the past, are the habitats that are being lost and destroyed due to their limited and specific habitat requirements.[17] Between the years of 1962 and 1974, the population estimated to an 8 to 12% drop. Based on intensive surveys and observations, it was counted that in 2015, there were 716 singing males within 39 acres in Texas.[18]

Threats

The main direct threat towards the golden-cheeked warbler is the rapid loss of habitats.[19] Their specific habitat needs place warblers at an extremely vulnerable position where urban development has taken a significant amount of the available habitat away. Over-browsing by White-tailed deer, Goat, and Ungulate are also believed to be a source of habitat destruction as they decrease the survival rate of seedling oaks and other deciduous trees, which are a key habitat for warblers. Furthermore, the Brown-headed cowbird which is a Brood parasite that lays eggs in other nests, then abandons the nest is still being looked at on how great its impact is on the Golden-cheeked Warbler population because often these warblers will raise the other young birds as well as their own.[20] As a result, the survivability of the young Golden-cheeked Warbler's is significantly reduced.

Ecology

The Golden-cheeked Warbler breeds in the juniper-oak woodlands. The bird starts to build its nest about 16–23 feet in the air around the end of March out of Ashe Juniper bark.[21] The male Warbler will use song and physical abuse against other males to establish a territory in close proximity to the previous year’s territory.[22] Warblers will stay with only one mate for the entirety of the breeding season. The female will produce 3-4 white eggs that are covered with brown and purple dots that will hatch 10–12 days later. The hatchlings grow rapidly and will leave the nest after 9–12 days. The family will stay together in their territory for up to a month, after which the hatchlings will become independent.[23]

Migration

Golden-cheeked Warblers will only remain in Texas for the breeding season, from March to June. They will migrate with other songbird species along Mexico’s Sierra Madre Oriental. By the first week of March, the Warblers will return to Texas to breed. During the winter season (November–February), Warblers will travel to Guatemala, Nicaragua, Honduras, and Mexico.[24]

Nesting

Once a female has chosen a mate, she alone builds the nest. The nest is made of strips of juniper bark, rootlets, grasses, cobwebs, cocoons, and can contain animal fur to line to the outer portions of the nest. Nearly all of warbler nests contain juniper bark, and it has been seen that females do not make a nest without the presence of the bark. Golden-cheeked warblers lay 3-4 creamy-white eggs, less than 3/4 inch long and ½ inch wide. Incubation begins one day before the last egg is laid. For approximately the 12 days, the female warbler incubates the eggs. The male is for the most part inattentive at this time, joining the female only when she forages for insects away from the nest.[25]

Location

The Golden-cheeked Warbler can be found in numerous state parks within Texas. These parks include the “Colorado Bend State Park (SP), Dinosaur Valley SP, Garner SP, Guadalupe River SP, Honey Creek State Natural Area (SNA), Hill Country SNA, Kerr Management Area, Longhorn Cavern SNA, Lost Maples SNA, Meridian SP, Pedernales Falls SP, and Possum Kingdom SP.”[26]

Feeding

The Golden-cheeked warbler is known to feed on various forms of insects and spiders, caterpillars are also noted as a primary source of food during the breeding season.[27][28] This species is completely insectivorous. The method for catching insects is by plucking them from all surfaces by being able to reach them through flight.[29]

In fiction

Susan Wittig Albert uses the golden-cheeked warbler as a plot device in her 1992 novel Thyme of Death.

See also

References

- ↑ BirdLife International (2013). "Dendroica chrysoparia". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2013.2. International Union for Conservation of Nature. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

- ↑ http://txtbba.tamu.edu/species-accounts/golden-cheeked-warbler/

- ↑ http://www.tpwd.state.tx.us/publications/pwdpubs/media/pwd_bk_w7000_0013_golden_cheeked_warbler.pdf

- ↑ http://ecos.fws.gov/speciesProfile/profile/speciesProfile.action?spcode=B07W

- ↑ http://birds.audubon.org/species/golwar4

- ↑ http://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Golden-cheeked_Warbler/lifehistory "Golden-cheeked warbler" Cornell Lab of Orinthology

- ↑ http://animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu/accounts/Dendroica_chrysoparia/"Dendroica chrysoparia golden-cheeked warbler" University of Michigan Museum of Zoology

- ↑ http://www.tpwd.state.tx.us/huntwild/wild/species/gcw/ "Golden-cheeked Warbler" Texas Parks and Wildlife.

- ↑ http://animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu/accounts/Dendroica_chrysoparia/"Dendroica chrysoparia golden-cheeked warbler" University of Michigan Museum of Zoology

- ↑ http://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Golden-cheeked_Warbler/lifehistory "Golden-cheeked warbler" Cornell Lab of Orinthology

- ↑ http://www.birdlife.org/datazone/speciesfactsheet.php? =9107 "Golden-cheeked warbler" BirdLife International

- ↑ "Golden-cheeked Warbler" Texas Parks and Wildlife.

- ↑ "Golden-cheeked Warbler" Texas Parks and Wildlife.

- ↑ http://animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu/accounts/Dendroica_chrysoparia/"Dendroica chrysoparia:golden-cheeked warbler" University of Michigan Museum of Zoology

- ↑ "Golden-cheeked Warbler" Texas Parks and Wildlife.

- ↑ http://birds.audubon.org/species/golwar4 "Golden-cheeked Warbler"

- ↑ http://www.tpwd.state.tx.us/publications/pwdpubs/media/pwd_bk_w7000_0013_golden_cheeked_warbler.pdf

- ↑ http://birds.audubon.org/species/golwar4

- ↑ http://www.tpwd.state.tx.us/publications/pwdpubs/media/pwd_bk_w7000_0013_golden_cheeked_warbler.pdf

- ↑ http://www.fws.gov/refuge/Balcones_Canyonlands/what_we_do/protecting_native_species.html

- ↑ Bird, J., Harding, M., Isherwood, I., Pople, R., Sharpe, C J, Wege, D. & Symes, A. (2014). Species factsheet: Dendroica chrysoparia. Birdlife International. Retrieved from http://www.birdlife.org/datazone/speciesfactsheet.php?id=9107

- ↑ Audubon Magazine. Golden-cheeked Warbler. Retrieved from: http://birds.audubon.org/species/golwar4

- ↑ Audubon Magazine. Golden-cheeked Warbler. Retrieved from: http://birds.audubon.org/species/golwar4

- ↑ Rappole, John H., King, David I., & Barrow Jr., Wylie C. (1999). Winter Ecology of the Endangered Golden-Cheeked Warbler. The Condor, 101-4, 762-770

- ↑ http://www.fws.gov/refuge/Balcones_Canyonlands/GCW.html

- ↑ Texas Park and Wildlife Department. (1990). Golden-cheeked Warbler. Retrieved from http://www.tpwd.state.tx.us/publications/pwdpubs/media/pwd_bk_w7000_0013_golden_cheeked_warbler.pdf

- ↑ http://www.arkive.org/golden-cheeked-warbler/dendroica-chrysoparia/

- ↑ http://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Golden-cheeked_Warbler/id

- ↑ http://birds.audubon.org/species/golwar4

Further reading

Books

- Harper SJ, Westervelt JD & Shapiro A-M. (2002). Management application of an agent-based model: Control of cowbirds at the landscape scale. In Gimblett, H Randy [Editor, Reprint Author] Integrating geographic information systems and agent-based modeling techniques for stimulating social and ecological processes:105-123, 2002. Oxford University Press, 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY, 10016.

- Ladd, C., and L. Gass. 1999. Golden-cheeked Warbler (Dendroica chrysoparia). In The Birds of North America, No. 420 (A. Poole and F. Gill, eds.). The Birds of North America, Inc., Philadelphia, PA.

- Pulich, W. M. 1976. The Golden-cheeked Warbler. Texas Parks and Wildlife Department. Austin, TX. 172pp.

- Shapiro A-MT, Harper SJ & Westervelt JD. (2004). The Fort Hood Avian Simulation Model-V: A spatially explicit population viability model for two endangered species. In Costanza, Robert [Editor, Reprint Author], Voinov, Alexey [Editor, Reprint Author] Landscape simulation modeling: A spatially explicit, dynamic approach:233-247, 2004. Springer-Verlag New York Inc., 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY, 10010-7858.

Thesis

- Reidy J.L. M.S. (2007). Golden-cheeked Warbler nest success and nest predators in urban and rural landscapes. University of Missouri, Columbia, Missouri.

- Lindsay DL. M.S. (2006). Genetic diversity of the endangered golden-cheeked warbler, Dendroica chrysoparia. University of Louisiana at Lafayette, United States, Louisiana.

- Coldren CL. Ph.D. (1998). The effects of habitat fragmentation on the golden-cheeked warbler. Texas A&M University, United States, Texas.

- Engels TM. Ph.D. (1995). The conservation biology of the golden-cheeked warbler (Dendroica chrysoparia). The University of Texas at Austin, United States, Texas.

- Hsu S-L. Ph.D. (1999). A model of environmental compromise between regulators and landowners under the Endangered Species Act. University of California, Davis, United States, California.

- Shaw DM. Ph.D. (1989). Applications of GIS and remote sensing for the characterization of habitat for threatened and endangered species. University of North Texas, United States, Texas.

- Stake MM. M.S. (2003). Golden-cheeked warbler nest predators and factors affecting nest predation. University of Missouri - Columbia, United States, Missouri.

Articles

- (1995). "Golden Cheeked Warbler" Discussed at Baylor During Academy. Baylor Business Review. vol 13, no 1. p. 17.

- Academy of Natural Sciences of P. (1999). Golden-cheeked warbler: Dendroica chrysoparia. Birds of North America. vol 0, no 420. pp. 1–23.

- Anders AD & Dearborn DC. (2004). Population trends of the endangered golden-cheeked warbler at Fort Hood, Texas, from 1992–2001. Southwestern Naturalist. vol 49, no 1. pp. 39–47.

- Anders AD & Marshall MR. (2005). Increasing the accuracy of productivity and survival estimates in assessing landbird population status. Conservation Biology. vol 19, no 1. pp. 66–74.

- Arnold KA. (2000). Texas. American Birds. vol 101, pp. 642–643.

- Bocetti CI, Hatfield JS & Beardmore CJ. (1996). Some advice and guidelines for biologists interested in conducting population viability analyses. Bulletin of the Ecological Society of America. p. PART 2) 42, 1996.

- Boice LP. (1998). Migratory bird conservation at Fort Hood. Endangered Species Update. vol 15, no 5. p. SS24.

- Bolsinger JS. (2000). Use of two song categories by Golden-cheeked Warblers. Condor. vol 102, no 3. pp. 539–552.

- Braun MJ, Braun DD & Terrill SB. (1986). Winter Records of the Golden-Cheeked Warbler Dendroica-Chrysoparia from Mexico. American Birds. vol 40, no 3. pp. 564–566.

- Cathey K. (1997). The endangered birds of Balcones Canyonlands NWR. Endangered Species Update. vol 14, no 11-12. p. SS20.

- David E. (2001). Extinction and blame. Orion. vol 20, no 3. p. 12.

- Dearborn DC & Sanchez LL. (2001). Do Golden-cheeked Warblers select nest locations on the basis of patch vegetation?. Auk. vol 118, no 4. pp. 1052–1057.

- DeBoer TS & Diamond DD. (2006). Predicting presence-absence of the endangered golden-cheeked warbler (Dendroica chrysoparia). Southwestern Naturalist. vol 51, no 2. pp. 181–190.

- Dunham AE, Akcakaya HR & Bridges TS. (2006). Using scalar models for precautionary assessments of threatened species. Conservation Biology. vol 20, no 5. pp. 1499–1506.

- Eisermann K & Schulz U. (2005). Birds of a high-altitude cloud forest in Alta Verapaz, Guatemala. Revista de Biologia Tropical. vol 53, no 3-4. pp. 577–594.

- Engels TM & Sexton CW. (1994). Negative correlation of blue jays and golden-cheeked warblers near an urbanizing area. Conservation Biology. vol 8, no 1. pp. 286–290.

- Fox JA & Nino-Murcia A. (2004). Species conservation banking: A solution to the conservation-development conflict. Ecological Society of America Annual Meeting Abstracts. vol 89, no 164.

- Gehlbach FR. (1967). New Records of Warblers in Texas. Southwestern Naturalist. vol 12, no 1. pp. 109–110.

- Graber AE, Davis CA & Leslie DM, Jr. (2006). Golden-cheeked Warbler males participate in nest-site selection. Wilson Journal of Ornithology. vol 118, no 2. pp. 247–251.

- Hunn E. (1973). Noteworthy Bird Observation from Chiapas Mexico. Condor. vol 75, no 4.

- James SM. (2002). Bridging the gap between private landowners and conservationists. Conservation Biology. vol 16, no 1. pp. 269–271.

- John HR, David K, Jeff D & Jorge Vega R. (2005). Factors Affecting Population Size in Texas' Golden-cheeked Warbler. Endangered Species Update. vol 22, no 3. p. 95.

- Johnson KW, Johnson JE, Albert RO & Albert TR. (1988). Sightings of Golden-Cheeked Warblers Dendroica-Chrysoparia in Northeastern Mexico. Wilson Bulletin. vol 100, no 1. pp. 130–131.

- Joseph ADA. (2003). Green laws threaten to surround Fort Hood. Human Events. vol 59, no 15. p. 5.

- Kroll JC. (1980). Habitat Requirements of the Golden-Cheeked Warbler Dendroica-Chrysoparia Management Implications. Journal of Range Management. vol 33, no 1. pp. 60–65.

- Lewis TJ, Ainley DG, Greenberg D & Greenberg R. (1974). A Golden-Cheeked Warbler on the Farallon Islands. Auk. vol 91, no 2. pp. 411–412.

- Lockwood MW. (1996). Courtship behavior of Golden-cheeked Warblers. Wilson Bulletin. vol 108, no 3. pp. 591–592.

- Lovette IJ & Hochachka WM. (2006). Simultaneous effects of phylogenetic niche conservatism and competition on avian community structure. Ecology. p. S) S14-S28, JUL 2006.

- Magness DR, Wilkins RN & Hejl SJ. (2006). Quantitative relationships among golden-cheeked warbler occurrence and landscape size, composition, and structure. Wildlife Society Bulletin. vol 34, no 2. pp. 473–479.

- Mike MS & Paul MC. (2001). Removal of host nestlings and fecal sacs by Brown-headed Cowbirds. The Wilson Bulletin. vol 113, no 4. p. 456.

- Ortego B. (2000). Summary of highest counts of individuals for the United States. American Birds. vol 101, pp. 661–666.

- Perrigo G, Brundage R, Barth R, Damude N, Benesh C, Fogg C & Gower J. (1990). Spring Migration Corridor of Golden-Cheeked Warblers in Tamaulipas Mexico. American Birds. vol 44, no 1. pp. 28–31.

- Peterson TR & Horton CC. (1995). ROOTED IN THE SOIL - HOW UNDERSTANDING THE PERSPECTIVES OF LANDOWNERS CAN ENHANCE THE MANAGEMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL DISPUTES. Q J Speech. vol 81, no 2. pp. 139–166.

- Petyk J. (2004). Predation of a Golden-cheeked Warbler nest by a Western Scrub-Jay. Wilson Bulletin. vol 116, no 3. pp. 269–271.

- Pulich WM. (1969). Golden-Cheeked Warbler Threatened Bird of the Cedar-G Brakes Dendroica-Chrysoparia Ecology Conservation. National Parks Magazine. vol 43, no 258. pp. 10–12.

- Quinn WJ & Penn JG. (2004). Quercus buckleyi overstory recruitment in undisturbed communities of central Texas. Ecological Society of America Annual Meeting Abstracts. vol 89, no 412.

- Rappole JH, King DI & Barrow WC, Jr. (1999). Winter ecology of the endangered Golden-cheeked Warbler. Condor. vol 101, no 4. pp. 762–770.

- Rappole JH, King DI & Diez J. (2003). Winter- vs. breeding-habitat limitation for an endangered avian migrant. Ecological Applications. vol 13, no 3. pp. 735–742.

- Rappole JH, King DI & Leimgruber P. (2000). Winter habitat and distribution of the endangered golden-cheeked warbler (Dendroica chrysoparia). Anim Conserv. vol 3, pp. 45–59.

- Rising JD. (1988). Phenetic Relationships among the Warblers in the Dendroica-Virens Complex and a Record of Dendroica-Virens from Sonora Mexico. Wilson Bulletin. vol 100, no 2. pp. 312–316.

- Shaw DM & Atkinson SF. (1990). An Introduction to the Use of Geographic Information Systems for Ornithological Research. Condor. vol 92, no 3. pp. 564–570.

- Smeins FE & Moses ME. (1994). Temporal analysis of golden-cheeked warbler habitat fragmentation using remote sensing and GIS. Bulletin of the Ecological Society of America. vol 75, no 2 PART 2. pp. 213–214.

- Stake MM. (2001). Predation by a Great Plains rat snake on an adult female Golden-cheeked Warbler. Wilson Bulletin. vol 113, no 4. pp. 460–461.

- Stake MM & Cavanagh PM. (2001). Removal of host nestlings and fecal sacs by Brown-headed Cowbirds. Wilson Bulletin. vol 113, no 4. pp. 456–459.

- Stake MM, Faaborg J & Thompson FR, III. (2004). Video identification of predators at Golden-cheeked Warbler nests. Journal of Field Ornithology. vol 75, no 4. pp. 337–344.

- Vidal RM, Macias-Caballero C & Duncan CD. (1994). The occurrence and ecology of the Golden-cheeked Warbler in the highlands of Northern Chiapas, Mexico. Condor. vol 96, no 3. pp. 684–691.

External links

- BirdLife Species Factsheet

- Balcones Canyonland Preserve with audio recordings of the two types of calls

- Golden-cheeked warblers in 2011 slideshow