Buff-breasted paradise kingfisher

| Buff-breasted paradise kingfisher | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Coraciiformes |

| Family: | Alcedinidae |

| Subfamily: | Halcyoninae |

| Genus: | Tanysiptera |

| Species: | T. sylvia |

| Binomial name | |

| Tanysiptera sylvia Gould, 1850 | |

The buff-breasted paradise-kingfisher (Tanysiptera sylvia) is a bird in the tree kingfisher subfamily, Halcyoninae. It is native to Australia, New Guinea and the Bismarck Archipelago and migrates in November from New Guinea to its breeding grounds in the rainforest of North Queensland, Australia. Like all paradise-kingfishers, this bird has colourful plumage with a red bill, buff breast and distinctive long tail streamers.

Taxonomy

The buff-breasted paradise-kingfisher was first described by John Gould in 1850 as Tanysiptera sylvia from specimens supplied by naturalist John MacGillivray from Cape York, Australia.[2] The genus name is derived from the Greek tanuo meaning “long” and pteron meaning “wing”, whilst sylvia is from the Latin silva, meaning "forest".[3] Until recently the species was known as the white-tailed kingfisher. The name buff-breasted paradise-kingfisher was first used in Australia by Graham Pizzey in 1980.[4][5]

The following subspecies are recognised:

- T. sylvia sylvia (Gould, 1850),[6] the nominate species, is found in Australia and New Guinea.

- T. sylvia salvadoriana (Ramsay, 1878),[7] after Conte Salvadorii (Italian ornithologist).[3] It is found in south west New Guinea and has paler underparts.[7]

- T. sylvia leucura (Neumann, 1915)[7] from the Greek, leuko meaning "white" and oura meaning "tail".[3] It is found on Umboi Island in the Bismarck Archipelago. It is larger with paler underparts and the tail is entirely white and shorter.[8]

- T. sylvia nigriceps (Sclater, 1977)[7] from the Latin, niger meaning "black" and Greek cephs meaning "head".[3] It is found in New Britain and Duke of York Islands in the Bismarck Archipelago.[7] It is larger with black cap and scapulars, paler underparts, blue and white tail, broader streamers, longer tails and different song.[8] T. nigriceps has recently been listed by IUCN as a separate species.[9]

Other vernacular names used include white-tailed kingfisher, white-tailed Tanysiptera (used by Gould 1848),[4] Australian paradise-kingfisher, long-tailed kingfisher, silver-tailed kingfisher, racquet-tailed kingfisher, black-headed kingfisher,[7] kinghunter,[10] Tcherwal-Tcherwal (Aboriginal language).[11]

Distribution and habitat

T. sylvia occurs in the southeast peninsula of New Guinea. During the breeding season it migrates to Australia where it is distributed in coastal north-east Queensland from islands in the Torres Strait and Cape York Peninsula south to Byfield, in central Queensland. Individual sightings have been recorded at Eurimbula National Park, south of Gladstone, and on islands of the Great Barrier Reef.[12][13][14][15]

The buff-breasted paradise-kingfisher inhabits lowland monsoon rainforest, and isolated patches of hill forest in areas where active termite mounds suitable for nesting are located. They usually perch in the mid-storey and lower canopy, coming to the ground to feed. In some areas they occur alongside the common paradise kingfishers.[8]

Description

Like all paradise-kingfishers, the buff-breasted is brightly coloured with a large red bill, rich rufous-buff underparts, blue or purple cap, crown and outer tail feathers, black eye stripes running down to the nape of its neck, red feet, white lower back and rump and long white or blue-and-white tail-feathers which varies geographically.[8] The identifying feature is the white patch on the centre of the upper back.[13] The juvenile has a brown bill, yellowish feet, is duller and lacks long tail feathers.[7]

An adult male is 35 cm (14 in) in length including the tail feathers which extend 13 cm (5.1 in) beyond the rest of the tail. An adult female is 30 cm (12 in), including much shorter tail feathers, extending 8 cm (3.1 in) beyond the rest of the tail. Tails vary in length but are approximately 18 cm (7.1 in). Tail-feathers of juveniles and immatures are shorter than adults. The tail feathers are often damaged towards the end of the breeding season, most likely from entering and leaving the burrow and regrow before the next mating season.[16][17][18] The wingspan for an adult male is 35 cm (14 in) and adult female is 34 cm (13 in). They weigh 45-50g (1.59-1.77 oz).[7]

Behaviour

The species shows signs of territorial behaviour in non-breeding grounds in New Guinea where single birds defend their resources. During the breeding season in Australia territories are defended by pairs.[19]

Breeding

In Australia nests are made in small termite mounds on the ground, on rotting logs or against the base of a tree. Nests have also been recorded in mounds attached to living trees with the bases 1.5–3 m (4.9–9.8 ft) above the ground. In New Britain a nest has been recorded in a tree hole 5 m (16 ft) above the ground. In New Guinea the kingfishers use termitaria on the ground as well as trees.[8][20] Breeding season in Australia begins immediately on arrival in early November. In New Britain breeding is in May, June and possibly December whilst in New Guinea breeding is in February.[8]

Mounds are typically 40–70 cm (16–28 in) high and 40–50 cm (16–20 in) wide.[21] An entrance, usually 4 cm (1.6 in) across[15] is made in the side about 35–50 cm (14–20 in) from the ground[22] Tunnel entrances have been observed on the downhill side of the mounds.[15] On arrival the birds immediately commence work on their nests,[23] usually spending 3–4 weeks burrowing out a 15 cm (5.9 in) tunnel. The floor of the chamber is flat and smooth with a rounded chamber at the end. No nesting material is used.[24] Birds may use the same mound in subsequent years but always have to dig a fresh tunnel as termites usually fill in the hole from the previous year.[11] Not all mounds that are excavated are used as nests.[15][25] Some are left inactive although they may be used when active nests are predated.[15] After the young have left the nest, a large amount of rubbish remains, including pinfeather covers, faeces, maggots and food scraps such as beetle legs. The nest chamber is very hot and strong smelling.[25] Nests are made in mounds where termites are active which may be due to termites maintaining a constant temperature suitable for incubating the eggs[20] or termites helping to keep the tunnel intact preventing collapse.[26]

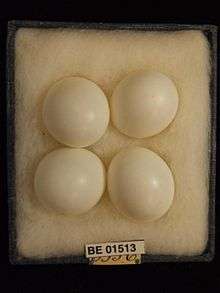

The buff-breasted paradise-kingfisher produces 1 clutch of eggs per year, producing a second clutch only if the first fails early in the breeding season.[20] The clutch is 3-4 white rounded eggs averaging 23 mm × 26 mm (0.91 in × 1.02 in).[22] They are incubated by both parents and hatch after about 23 days. Fledging is approximately 25 days and birds have been observed leaving the nest and flying directly on to a branch.[15] The average fledging success rate for a pair of kingfishers is 1.5.[20]

Diet

The buff-breasted paradise-kingfisher hunts on the ground and from the foliage in the middle to lower levels of the forest. It feeds on phasmids, earthworms, beetles, insect larvae, spiders, skinks and small frogs, snails and has been observed holding a small tortoise.[8][11] The young are fed by both parents.[20]

Migration

The subspecies T. s. sylvia breeds in north east Queensland from November to early April before migrating north to New Guinea for the non-breeding season.[8] Juveniles depart up to 3 weeks after adults.[15] The distance travelled for each population ranges between 400 to 2000 km depending on the breeding and non-breeding locations. The buff-breasted paradise-kingfisher is believed to migrate in flocks at night as large numbers of birds suddenly appear in Queensland rainforests at the start of the breeding season early in the morning.[20]

Many birds are believed to perish during the 80 km flight from New Guinea to Australia. The birds have been recorded flying close to the water and drowning in sea spray,[10] colliding with the Booby Island Lighthouse,[27] and arriving at their destination in a state of severe exhaustion.[11] Populations breeding in New Guinea and New Britain are believed to be resident.[28]

Vocalisation

Despite its bright colours, the buff-breasted paradise-kingfisher is often difficult to see in the rainforest and is best located by its distinctive calls.[8] It is usually noisier early in the season when the males are establishing territories and courting. Based on studies in New Guinea the bird calls much less frequently during the non-breeding season.[19]

The most commonly heard call has been described as an ascending ch-kow, ch-kow,[25] chop chop,[7] chuga, chuga[17] or tcherwill tcherwill[11] repeated 4-5 times. Each call is usually accompanied by continuous flicking of the tail,[19][25] often pointing their heads skyward, pulling their wings downwards and fluffing up their white feathers. A soft descending trill is often used when approaching the nest and occasionally while perched. It is regarded as a sign of uncertainty and is said to be a reassuring call to its mate.[25] Explosive shrieks can be heard when alarmed.[7] In New Britain the song is a rising and falling series of songbird-like chirps.[8] In New Guinea it is described as a soft purring trill.[13] The call of nestlings is described as a soft but constant whirring sound.[11] The birds can call with the mouth closed or when holding food in its bill.[25]

Threats

Natural predators of nest eggs include snakes and goannas, whilst a butcherbird has also been observed preying on young.[20] Land clearing and habitat loss in New Guinea have the potential to impact on the breeding populations in Australia.[19][29]

Culture

The buff-breasted paradise-kingfisher has been depicted on the 22 cent Australian stamp in 1980 and the 25 toea Papua New Guinea stamp in 1981.[30]

References

- ↑ BirdLife International (2012). "Tanysiptera sylvia". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2014.3. International Union for Conservation of Nature. Retrieved 21 March 2015.

- ↑ Yarrell, W (1850). 'July 23, 1850', Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London, 18(1), 200-7.

- 1 2 3 4 Lederer, R & Burr, C (2014). Latin for birdwatchers. Crows Nest, NSW: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 1-76-011064-7.

- 1 2 Fraser, I, Gray, J & CSIRO (Australia) (2013). Australian bird names : a complete guide. Collingwood, Vic.: CSIRO Publishing. ISBN 0-64-310469-0.

- ↑ Pizzey, G (1980). A field guide to the birds of Australia. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-00-219201-2.

- ↑ Christidis, L & Boles, WE (2008). Systematics and taxonomy of Australian birds. Collingwood, Vic.: CSIRO Publishing. ISBN 978-0-643-09602-8.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Higgins, Peter Jeffrey (1999). Handbook of Australian, New Zealand & Antarctic birds. v.4, Melbourne, Vic.: Oxford University Press. pp.1113-1122. ISBN 0 19-553071-3

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Fry, CH & Fry, K (1999). Kingfishers, bee-eaters & rollers. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. p.118-119. ISBN 0-691-04879-7.

- ↑ BirdLife International (2014). Tanysiptera nigriceps. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2014.3. <http://www.iucnredlist.org/details/summary/22725840/0>. Downloaded on 20 March 2015.

- 1 2 Chisholm, A (1932). "The White-tailed Kingfisher". Emu 32(2), 81-3.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Hollands, D (1999). Kingfishers and kookaburras : jewels of the Australian bush. Frenchs Forest, N.S.W.: Reed New Holland. p.102

- ↑ Nix, H (1984). "The buff-breasted paradise kingfisher in central Queensland". Sunbird 14(4), 77-9.

- 1 2 3 Pratt, TK, Beehler, BM, Bishop, KD, Coates, BJ, Diamond, JM, Lecroy, M, Anderton, J, Coe, J, Zimmerman (2015). Birds of New Guinea (2nd ed). Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. p.387

- ↑ Weineke, J (1988). 'The birds of Magnetic Island, North Queensland' Sunbird. 18(1) 1-22.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Black, R (2005). "Observations of buff-breasted paradise kingfisher Tanysiptera sylvia breeding in Byfield, central Queensland". Sunbird 35(2), 13

- ↑ Barnard, HG (1911). "Field notes from Cape York". Emu 11(1) 17-32.

- 1 2 Andrews, M (1993). "Further observations on nests of the Buff-breasted Paradise-kingfisher near Mackay". Sunbird 22(2), 41-3.

- ↑ Strahan, R (1994). Cuckoos, nightbirds & kingfishers of Australia. Sydney, NSW: Angus & Robertson. pp. 160-162. ISBN 0-207-18522-0

- 1 2 3 4 Legge, S, Murphy, S, Igag, P & Mack, AL (2004). "Territoriality and density of an Australian migrant, the Buff-breasted Paradise Kingfisher, in the New Guinean non-breeding grounds". Emu 104(1), 15-20.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Legge, S., Heinsohn, R (2001). "Kingfishers in paradise: the breeding biology of Tanysiptera sylvia at the Iron Range National Park, Cape York." The Australian Journal of Zoology. 49(1) 85-98.

- ↑ MacGillivray, W (1913). "Notes on some North Queensland birds". Emu 13(3), 132-86.

- 1 2 Readers Digest (2003). (2nd ed). Reader's Digest complete guide to Australian birds. Surry Hills, NSW: Reader's Digest. p.326.

- ↑ Gill, HB (1970). "Birds of Innisfail and hinterland". Emu 70(3), 105-16.

- ↑ Beruldsen, G (1980). A field guide to nests & eggs of Australian birds. Adelaide, S.A.: Rigby.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Gill, HB (1963). "The White-tailed Kingfisher, Tanysiptera sylvia. Emu 63(4), 273-6.

- ↑ Brightsmith, DJ (2000). "Use of arboreal termitaria by nesting birds in the Peruvian Amazon". The Condor 102(3) 529-38.

- ↑ Draffan, R, Garnett, S & Malone, G (1983). "Birds of the Torres Strait: an annotated list and biogeographical analysis". Emu 83(4), 207-34.

- ↑ Bell, HL (1981). "Information on New Guinean kingfishers, Alcedinidae". Ibis 123(1), 51-61.

- ↑ Sizer, N & Plouvier, D (2000). Increased investment and trade by Transnational Logging Companies in Africa, the Caribbean, and the Pacific: Implications for the sustainable management and conservation of tropical forests, World Wildlife Fund - Belgium.<http://pdf.wri.org/transnational_logging.pdf>.Downloaded on 22 March 2015.

- ↑ Birds of the World on Postage Stamps. http://www.bird-stamps.org/cspecies/8908400.htm Downloaded on 23 March 2015.

External links

| Wikispecies has information related to: Tanysiptera sylvia |