Billy Mitchell

| William L. "Billy" Mitchell | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

December 29, 1879 Nice, France |

| Died |

February 19, 1936 (aged 56) New York City, New York |

| Buried at | Forest Home Cemetery, Milwaukee, Wisconsin |

| Allegiance |

|

| Service/branch |

|

| Years of service | 1898–1926 |

| Rank |

|

| Commands held | Air Service, Third Army – AEF |

| Battles/wars | |

| Awards |

Distinguished Service Cross Distinguished Service Medal World War I Victory Medal Congressional Gold Medal (posthumous) |

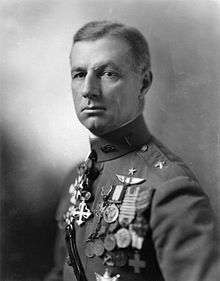

William Lendrum "Billy" Mitchell (December 29, 1879 – February 19, 1936) was a United States Army general who is regarded as the father of the United States Air Force.[1]

Mitchell served in France during World War I and, by the conflict's end, commanded all American air combat units in that country. After the war, he was appointed deputy director of the Air Service and began advocating increased investment in air power, believing that this would prove vital in future wars. He argued particularly for the ability of bombers to sink battleships and organized a series of bombing runs against stationary ships designed to test the idea.

He antagonized many administrative leaders of the Army with his arguments and criticism and, in 1925, was returned from appointment as a brigadier general to his permanent rank of colonel due to his insubordination. Later that year, he was court-martialed for insubordination after accusing Army and Navy leaders of an "almost treasonable administration of the national defense"[2] for investing in battleships instead of aircraft carriers. He resigned from the service shortly afterward.

Mitchell received many honors following his death, including a commission by President Franklin D. Roosevelt as a major general. He is also the only individual for whom an American military aircraft design, the North American B-25 Mitchell, is named.

Early life

.jpg)

Born in Nice, France, to John L. Mitchell, a wealthy Wisconsin senator[3] and his wife Harriet. Mitchell grew up on an estate in what is now the Milwaukee suburb of West Allis, Wisconsin. His grandfather Alexander Mitchell, a Scotsman, was the wealthiest man in Wisconsin for his generation and established what became the Milwaukee Road railroad and the Marine Bank of Wisconsin. Mitchell Park and the shopping precinct of Mitchell Street were named in honor of Alexander. Mitchell's sister Ruth fought with the Chetniks in Yugoslavia during World War II and later wrote a book about her brother, My Brother Bill.

Billy Mitchell graduated from Columbian College of George Washington University, where he was a member of Phi Kappa Psi Fraternity.[4] He then enlisted as a private at age 18 in Company M of the 1st Wisconsin Infantry Regiment on May 14, 1898, early in the Spanish–American War. Quickly gaining a commission due to his father's influence, he joined the U.S. Army Signal Corps.

Following the cessation of hostilities, Mitchell remained in the Army. He predicted as early as 1906, while an instructor at the Army's Signal School in Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, that future conflicts would take place in the air, not on the ground.

A member of one of Milwaukee's most prominent families, Billy Mitchell was probably the first person with ties to Wisconsin to see the Wright Brothers plane fly. In 1908, when a young Signal Corps officer, Mitchell observed Orville Wright's flying demonstration at Fort Myer, Virginia. Mitchell took flight lessons at the Curtiss Aviation School at Newport News, Virginia.

In March 1912, after assignments in the Philippines and Alaska Territory that saw him tour battlefields of the Russo-Japanese War and conclude that war with Japan was inevitable one day, Mitchell was one of 21 officers selected to serve on the General Staff—at the time, its youngest member at age 32. Ironically, he appeared in August 1913 at legislative hearings considering a bill to make Army aviation a branch separate from the Signal Corps and testified against the bill. As the only Signal Corps officer on the General Staff, he was chosen as temporary head of the Aviation Section, U.S. Signal Corps, a predecessor of the present day United States Air Force, in May 1916, when its head was reprimanded and relieved of duty for malfeasance in the section. Mitchell administered the section until the new head, Lieutenant Colonel George O. Squier, arrived from attaché duties in London, England, where World War I was in progress, then became his permanent assistant. In June, he took private flying lessons at the Glenn Curtiss Aviation School because he was proscribed by law from aviator training by age and rank, at an expense to himself of $1,470 (approximately $33,000 in 2015).[5] In July 1916, he was promoted to major and appointed Chief of the Air Service of the First Army.[6]

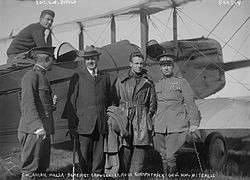

World War I

When the United States declared war on Germany on April 6, 1917, Mitchell was in Spain en route to France as an observer.[3] He arrived in Paris on April 10, and set up an office for the Aviation Section from which he collaborated extensively with British and French air leaders such as General Hugh Trenchard, studying their strategies as well as their aircraft. On April 24, he made the first flight by an American officer over German lines, flying with a French pilot. Before long, Mitchell had gained enough experience to begin preparations for American air operations. Mitchell rapidly earned a reputation as a daring, flamboyant, and tireless leader. In May, he was promoted to lieutenant colonel. He was promoted to the temporary rank of colonel on October 10, 1917 to rank from August 5.

In September 1918, he planned and led nearly 1,500 British, French, and Italian aircraft in the air phase of the Battle of Saint-Mihiel, one of the first coordinated air-ground offensives in history.[3] He was elevated to the rank of (temporary) brigadier general on October 14, 1918 and commanded all American air combat units in France. He ended the war as Chief of Air Service, Group of Armies, and became Chief of Air Service, Third Army after the armistice.

Recognized as one of the top American combat airmen of the war alongside aces such as his good friend, Eddie Rickenbacker, he was probably the best-known American in Europe. He was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross, the Distinguished Service Medal, the World War I Victory Medal with eight campaign clasps, and several foreign decorations. Despite his superb leadership and his fine combat record, he alienated many of his superiors during and after his 18 months of service in France.[3]

Post-war advocate of air power

Return from Europe

Returning to the United States in January 1919, it had been widely expected throughout the Air Service that Mitchell would receive the post-war assignment of Director of Air Service. Instead, he returned to find that Maj. Gen. Charles T. Menoher, an artilleryman who had commanded the Rainbow Division in France, had been appointed director on the recommendation of his classmate General Pershing, to maintain operational control of aviation by the ground forces.[9]

Mitchell received appointment on February 28, 1919, as Director of Military Aeronautics,[10] to head the flying component of the Air Service, but that office was in name only as it was a wartime agency that would expire six months after the signing of a peace treaty. Menoher instituted a reorganization of the Air Service based on the divisional system of the AEF, eliminating the DMA as an organization, and Mitchell was assigned as Third Assistant Executive, in charge of the Training and Operations Group, Office of Director of Air Service (ODAS), in April 1919. He maintained his temporary wartime rank of brigadier general until June 18, 1920, when he was reduced to lieutenant colonel, Signal Corps (Menoher was reduced to brigadier general in the same orders).[11]

When the Army was reorganized by Congress on June 4, 1920, the Air Service was recognized as a combatant arm of the line, third in size behind the Infantry and Artillery. On July 1, 1920, Mitchell was promoted to the Regular Army (i.e., permanent) rank of colonel in the Signal Corps, but also received a recess appointment (as did Menoher) on July 16 to become Assistant Chief of Air Service with the rank of brigadier general. On July 30, 1920, he was transferred and promoted to the permanent rank of colonel, Air Service, with date of rank from July 1, placing him first in seniority among all Air Service branch officers. On March 4, 1921, Mitchell was appointed Assistant Chief of Air Service by new President Warren G. Harding with consent of the Senate. On April 27, Mitchell was reappointed as a brigadier general with date of rank retroactive to July 2, 1920.[10]

Mitchell did not share in the common belief that World War I would be the war to end war. "If a nation ambitious for universal conquest gets off to a flying start in a war of the future," he said, "it may be able to control the whole world more easily than a nation has controlled a continent in the past."[12]

He returned from Europe with a fervent belief that within a near future, possibly within ten years, air power would become the predominant force of war, and that it should be united entirely in an independent air force equal to the Army and Navy. He found encouragement in a number of bills before Congress proposing a Department of Aeronautics that included an air force separate from either the Army or Navy, primarily legislation introduced concurrently in August 1919 by Senator Harry New of Indiana and Representative Charles F. Curry of California, influenced by the recommendations of a fact-finding commission sent to Europe under the direction of Assistant Secretary of War Benedict Crowell in early 1919 that contradicted the findings of Army boards and advocated an independent air force.

Friction with the Navy

Mitchell believed that the use of floating bases was necessary to defend the nation against naval threats, but the Chief of Naval Operations, Admiral William S. Benson, had dissolved Naval Aeronautics as an organization early in 1919, a decision later reversed by Assistant Secretary of the Navy, Franklin D. Roosevelt. However, senior Naval Aviators feared that land-based aviators in a "unified" independent air force would no more understand the requirements of sea-based aviation than ground forces commanders understood the capabilities and potential of air power, and vigorously resisted any alliance with Mitchell.

The Navy's civilian leadership was equally opposed, if for other reasons. On April 3, Mitchell met with Assistant Secretary of the Navy Franklin D. Roosevelt and a board of admirals to discuss aviation, and Mitchell urged the development of naval aviation because of the growing obsolescence of the surface fleet. His assurances that the Air Service could develop whatever bomb was needed to sink a battleship, and that a national defense organization of land, sea, and air components was essential and inevitable, were met with cool hostility. Mitchell found his ideas publicly denounced as "pernicious" by Roosevelt.[13] Convinced that within as soon as ten years strategic bombardment would become a threat to the United States and make the Air Service the nation's first line of defense instead of the Navy, he began to set out to prove that aircraft were capable of sinking ships to reinforce his position.[14][15][16]

His relations with superiors continued to sour as he began to attack both the War and Navy Departments for being insufficiently farsighted regarding airpower.[3] He advocated the development of a number of aircraft innovations, including bombsights, sled-runner landing gear for winter operations, engine superchargers, and aerial torpedoes. He ordered the use of aircraft in fighting forest fires and border patrols, and encouraged the staging of a transcontinental air race, a flight around the perimeter of the United States. He also encouraged Army pilots to challenge speed, endurance and altitude records. In short, he encouraged anything that would further develop the use of aircraft, and that would keep aviation in the news.

Project B: Anti-ship bombing demonstration

In February 1921, at the urging of Mitchell, who was anxious to test his theories of destruction of ships by aerial bombing, Secretary of War Newton Baker and Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels agreed to a series of joint Army-Navy exercises, known as Project B, to be held that summer in which surplus or captured ships could be used as targets.

Mitchell was concerned that the building of dreadnoughts was taking precious defense dollars away from military aviation. He was convinced that a force of anti-shipping airplanes could defend a coastline with more economy than a combination of coastal guns and naval vessels. A thousand bombers could be built at the same cost as one battleship, and could sink that battleship.[17] Mitchell infuriated the Navy by claiming he could sink ships "under war conditions", and boasted he could prove it if he were permitted to bomb captured German battleships.

The Navy reluctantly agreed to the demonstration after news leaked of its own tests. To counter Mitchell, the Navy had sunk the old battleship Indiana near Tangier Island, Virginia, on November 1, 1920, using its own airplanes. Daniels had hoped to squelch Mitchell by releasing a report on the results written by Captain William D. Leahy stating that, "The entire experiment pointed to the improbability of a modern battleship being either destroyed or completely put out of action by aerial bombs." When the New-York Tribune revealed that the Navy's "tests" were done with dummy sand bombs and that the ship was actually sunk using high explosives placed on the ship, Congress introduced two resolutions urging new tests and backed the Navy into a corner.[18]

In the arrangements for the new tests, there was to be a news blackout until all data had been analyzed at which point only the official news report would be released; Mitchell felt that the Navy was going to bury the results. The Chief of the Air Corps attempted to have Mitchell dismissed a week before the tests began, reacting to Navy complaints about Mitchell's criticisms, but the new Secretary of War John W. Weeks backed down when it became apparent that Mitchell had widespread public and media support.[19]

1st Provisional Air Brigade

On May 1, 1921, Mitchell assembled the 1st Provisional Air Brigade, an air and ground crew of 125 aircraft and 1,000 men at Langley Field in Hampton, Virginia, using six squadrons from the Air Service:

- Air Service Field Officers School, Langley Field, Virginia, (SE-5 fighters)

- 50th Squadron (Observation) (later 431st Bomb Squadron)

- 88th Squadron (later 436th Bomb Squadron)

- 2nd Bombardment Group (later 2nd Bomb Group), Kelly Field, Texas (SE-5 fighters, Martin NBS-1, Handley-Page O/400, and Caproni CA-5 bombers)

- 7th Observation Group (Second Corps Area), (now the 7th Operations Group), Mitchel Field, New York (DH-4 and Douglas O-2 observation planes)

Mitchell took command on 27 May after testing bombs, fuses, and other equipment at Aberdeen Proving Ground and began training in anti-ship bombing techniques. Alexander Seversky, a veteran Russian pilot who had bombed German ships in the Great War, joined the effort, suggesting the bombers aim near the ships so that expanding water pressure from the underwater blasts would stave in and separate hull plates. Further discussion with Captain Alfred Wilkinson Johnson, Commander, Naval Air Force U.S. Atlantic Fleet aboard USS Shawmut, confirmed that near-miss bombs would inflict more damage than direct hits; near-misses would cause an underwater concussive effect against the hull.[19][20]

Rules of engagement

The Navy and the Air Service were at cross purposes regarding the tests. Supported by General Pershing, the Navy set rules and conditions that enhanced the survivibility of the targets, stating that the purpose of the tests was to determine how much damage ships could withstand. The ships had to be sunk in at least 100 fathoms of water (so as not to become navigational hazards), and the Navy chose an area 50 mi (80 km) off the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay rather than either of two possible closer areas, minimizing the effective time the Army's bombers would have in the target area. The planes were forbidden from using aerial torpedoes, would be permitted only two hits on the battleship using their heaviest bombs, and would have to stop between hits so that a damage assessment party could go aboard. Smaller ships could not be struck by bombs larger than 600 pounds, and also were subject to the same interruptions in attacks.[21][22]

Mitchell held to the Navy's restrictions for the tests of June 21, July 13 and 18, and successfully sank the ex-German destroyer G-102 and the ex-German light cruiser Frankfurt in concert with Navy aircraft. On each of these demonstrations the ships were first attacked by SE-5 fighters strafing and bombing the decks of the ships with 25-pound anti-personnel bombs to simulate suppression of antiaircraft fire, followed by attacks from Martin NBS-1 (Martin MB-2) twin-engine bombers using high explosive demolition bombs. Mitchell observed the attacks from the controls of his DH-4 aircraft, nicknamed The Osprey.

Sinking of the Ostfriesland

_-_NH_57483.jpg)

_in_camouflage_coat%2C_1918_edit.jpg)

On July 20, 1921, the Navy brought out the ex-German World War I battleship, Ostfriesland. One day of scheduled 230, 550, and 600 lb (270 kg) bomb attacks by Navy, Marine Corps, and Army aircraft settled the Ostfriesland three feet by the stern with a five-degree list to port. She was taking on water. Further bombing was delayed a day, the Navy claiming due to rough seas that prevented their Board of Observers from going aboard, the Air Service countering that as the Army bombers approached, they were ordered not to attack. Mitchell's bombers were forced to circle for 47 minutes, as a result of which they dropped only half their bombs, and none of their large bombs.[23]

On the morning of July 21, in accordance with a strictly orchestrated schedule of attacks, five NBS-1 bombers led by 1st Lt. Clayton Bissell dropped a single 1,100 lb bomb each, scoring three direct hits. The Navy stopped further drops, although the Army bombers had nine bombs remaining, to assess damage. By noon, Ostfriesland had settled two more feet by the stern and one foot by the bow.

At this point, Capt. Walter R. Lawson's flight of bombers, consisting of two Handley-Page O/400 and six NBS-1 bombers loaded with 2,000 lb (910 kg) bombs, was dispatched.[24] One Handley Page dropped out for mechanical reasons, but the NBS-1s dropped six bombs in quick succession between 12:18 pm and 12:31 pm. Bomb aiming points were for the water near the ship. Mitchell described Lawson's attack, "Four bombs hit in rapid succession, close along side the Ostfriesland. We could see her rise eight to ten feet between the terrific blows from under water. On the fourth shot, Capt Streett, sitting in the back seat of my plane stood up and waving both arms shouted, "She is gone!" [24] There were no direct hits but at least three of the bombs landed close enough to rip hull plates as well as cause the ship to roll over. The ship sank at 12:40 pm, 22 minutes after the first bomb, with a seventh bomb dropped by the Handley Page on the foam rising up from the sinking ship.[25] Nearby the site, observing, were various foreign and domestic officials aboard the USS Henderson.

Although Mitchell had stressed "war-time conditions", the tests were under static conditions and the sinking of the Ostfriesland was accomplished by violating rules agreed upon by General Pershing that would have allowed Navy engineers to examine the effects of smaller munitions. Navy studies of the wreck of the Ostfriesland show she had suffered little topside damage from bombs and was sunk by progressive flooding that might have been stemmed by a fast-acting damage control party on board the vessel. Mitchell used the sinking for his own publicity purposes, though his results were downplayed in public by General of the Armies John J. Pershing who hoped to smooth Army/Navy relations.[23] The efficacy of the tests remain in debate to this day.

Nevertheless, the test was highly influential at the time, causing budgets to be redrawn for further air development and forcing the Navy to look more closely at the possibilities of naval airpower.[26] Despite the advantages enjoyed by the bombers in the artificial exercise, Mitchell's report stressed points which would later be highly influential in war:

...sea craft of all kinds, up to and including the most modern battleships, can be destroyed easily by bombs dropped from aircraft, and further, that the most effective means of destruction are bombs. [They] demonstrated beyond a doubt that, given sufficient bombing planes—in short an adequate air force—aircraft constitute a positive defense of our country against hostile invasion.[27]

The fact of battleship sinking was indisputable, and Mitchell repeated the performance twice in tests conducted with like results on the obsolete U.S. pre-dreadnought battleship Alabama in September 1921, and the battleships Virginia and New Jersey in September 1923.[28] The latter two ships were subjected to teargas attacks and hit with specially designed 4,300 lb (2,000 kg) demolition bombs.[29]

Aftermath of the bombing tests

The bombing tests had several immediate and turbulent results. Almost immediately the Navy and President Harding were incensed by an apparent demonstration of naval weakness just after Harding had announced on July 10 invitations to other naval powers to gather in Washington for a conference on the limitation of naval armaments. Statements asserting the obsolescence of the battleship by disarmament proponents in Congress such as Senator William Borah heightened official anxiety. Both services tried to defuse the results by reports from the Joint Board and General Pershing dismissing Mitchell's claims and suppressing his report, but the latter was leaked to the press.[30]

In September, General Charles T. Menoher forced a showdown over Mitchell as the bombing tests continued. Menoher confronted Secretary Weeks and demanded that Weeks either relieve Mitchell as Assistant Chief of Air Corps or he would resign. On October 4, Weeks allowed Menoher to resign and return to the ground forces "for personal reasons". A reciprocal resignation offer from Mitchell was refused.[31]

Major General Mason Patrick was again chosen by Pershing to sort out a mess in the Air Service and became the new Chief on October 5. Patrick made it clear to Mitchell that although he would accept Mitchell's expertise as counsel, all decisions would be made by Patrick. When Mitchell soon got into a minor but embarrassing protocol rift with Rear Admiral William A. Moffett at the start of the naval arms limitation conference, Patrick assigned him to an inspection tour of Europe with Alfred V. Verville and Lieutenant Clayton Bissell that lasted the duration of the conference over the winter of 1921–22.[31][32]

West Virginia

Mitchell was dispatched by President Harding to West Virginia to stop the warfare that had broken out between the United Mine Workers, Stone Mountain Coal Company, the Baldwin-Felts Detective Agency, and other groups after the Matewan Massacre.[33] Miners outraged by the ambush slaying of Matewan Police Chief Sid Hatfield by agents for the coal company marched on Mingo and Logan County leading to the Battle of Blair Mountain, August 25 to September 2, 1921. On August 26, Mitchell commanded Army bombers from Maryland to Charleston, West Virginia. Mitchell told the press that Army bombers alone could end the "Mingo War" by dropping tear gas on the miners. A private army of 3,000 led by Sheriff Don Chafin and financed by the Coal Operators Association engaged in gun battles and used private planes to drop dynamite charges and World War I surplus gas and explosive bombs against an estimated 13,000 miners. Neither side responded to President Harding's August 30 proclamation to cease hostilities. In the last days of the civil disturbance, Mitchell's bombers flew several reconnaissance missions but did not engage in combat; one bomber crashed on a return flight, killing three crew members. On September 3, surrounded by 2,000 Army troops, Chafin's force dispersed and most miners went home although some surrendered to the Army. Later, Mitchell cited the "Mingo War" as an example of the potential for air power in civil disturbances.[34]

Promoting air power

The day has passed when armies on the ground or navies on the sea can be the arbiter of a nation's destiny in war. The main power of defense and the power of initiative against an enemy has passed to the air. – November 1918[35]

In 1922, while in Europe for General Patrick, Mitchell met the Italian air power theorist Giulio Douhet and soon afterwards an excerpted translation of Douhet's The Command of the Air began to circulate in the Air Service. In 1924, Gen. Patrick again dispatched him on an inspection tour, this time to Hawaii and Asia, to get him off the front pages. Mitchell came back with a 324-page report that predicted future war with Japan, including the attack on Pearl Harbor. Of note, Mitchell discounted the value of aircraft carriers in an attack on the Hawaiian Islands, believing they were of little practical use because they were incapable of operating effectively on the high seas, nor capable of delivering "sufficient aircraft in the air at one time to insure a concentrated operation."[36] Mitchell believed instead, a surprise attack on the Hawaiian Islands would be conducted by land-based aircraft operating from islands in the Pacific.[37] His report, published in 1925 as the book Winged Defense, foretold wider benefits of an investment in air power, believing it at the time, and for the future, " a dominating factor in the world's development", both for national defense and economic benefit.[38] Winged Defense sold only 4,500 copies between August 1925 and January 1926, the months surrounding the publicity of the court martial, and so Mitchell did not reach a wide audience.[39]

Friction and demotion

Mitchell experienced difficulties within the Army, notably with his superiors when he appeared before the Lampert Committee of the U.S. House of Representatives and sharply castigated Army and Navy leadership.[3] The War Department had endorsed a proposal to establish a "General Headquarters Air Force" as a vehicle for modernization and expansion of the Air Service, to be funded through shared appropriations for aviation with the Navy, but shelved the plan when the Navy refused, incensing Mitchell.

In March 1925, when Mitchell's term as Assistant Chief of the Air Service expired, he reverted to his permanent rank of colonel and was transferred to San Antonio, Texas, as air officer to a ground forces corps.[3] Although such demotions were not unusual in demobilizations (Patrick himself had gone from major general to colonel upon returning to the Army Corps of Engineers in 1919), the move was widely seen as punishment and exile,[3] since Mitchell had petitioned to remain as Assistant Chief when his term expired, and his transfer to an assignment with no political influence at a relatively unimportant Army base had been directed by Secretary of War John Weeks.

Court-martial

In response to the Navy's first helium-filled rigid airship Shenandoah crashing in a storm in September 1925, killing 14 of the crew, and the loss of three seaplanes on a flight from the West Coast to Hawaii, Mitchell issued a statement accusing senior leaders in the Army and Navy of incompetence and "almost treasonable administration of the national defense."[40] In October 1925, a charge with eight specifications was proffered against Mitchell on the direct order of President Calvin Coolidge, accusing him of violation of the 96th Article of War, an omnibus article that Mitchell's chief counsel, Congressman Frank Reid, declared to be "unconstitutional" as a violation of free speech.[41] The court martial began in early November and lasted for seven weeks.

The youngest of the 12 judges was Major General Douglas MacArthur, who later described the order to sit on Mitchell's court-martial as "one of the most distasteful orders I ever received."[42] Of the thirteen judges, none had aviation experience and three were removed by defense challenges for bias, including Major General Charles P. Summerall, the president of the court. The case was then presided over by Major General Robert Lee Howze.[43] Among those who testified for Mitchell were Eddie Rickenbacker, Hap Arnold, Carl Spaatz and Fiorello La Guardia. The trial attracted significant interest, and public opinion supported Mitchell.[44]

However, the court found the truth or falsity of Mitchell's accusations to be immaterial to the charge and on December 17, 1925, found him "guilty of all specifications and of the charge". The court suspended him from active duty for five years without pay, which President Coolidge later amended to half-pay.[3] The generals ruling in the case wrote, "The Court is thus lenient because of the military record of the Accused during the World War."[45] MacArthur (who himself in 1951 was removed from duty for similar reasons) later said he had voted to acquit, and Fiorello La Guardia said that MacArthur's "not guilty" ballot had been found in the judges' anteroom.[46] MacArthur felt "that a senior officer should not be silenced for being at variance with his superiors in rank and with accepted doctrine."[42]

Later life

Mitchell resigned instead on February 1, 1926, and spent the next decade writing and preaching air power to all who would listen.[3] However, his departure from the service sharply reduced his ability to influence military policy and public opinion.

Mitchell viewed the election of his one-time antagonist Franklin D. Roosevelt as advantageous for air power, and met with him early in 1932 to brief him on his concepts for a unification of the military in a Department of Defense. His ideas intrigued and interested Roosevelt. Mitchell believed he might receive an appointment as Assistant Secretary of War for Air or perhaps even Secretary of War in a Roosevelt administration, but neither prospect materialized.[3]

In 1926, Mitchell made his home with his wife Elizabeth at the 120-acre (0.49 km2) Boxwood Farm in Middleburg, Virginia, which remained his primary residence until his death.[47] He died of a variety of ailments, including a bad heart and an extreme case of influenza,[3] in a hospital in New York City on February 19, 1936, at the age of 56, and was buried at Forest Home Cemetery in Milwaukee, Wisconsin.[48]

Mitchell's son, John, joined the Army in 1941. Promoted to First Lieutenant in the 4th Armored Division, he died from a blood infection in 1942.[49] Mitchell's first cousin, the Canadian George Croil, went on to secure an autonomous status for the Royal Canadian Air Force and in 1938 became its first Chief of the Air Staff.[50]

Military and civilian awards

Note – Incomplete list. The dates indicate the year the award was presented and not necessarily the date it was earned.

Mitchell's military awards

|

Mitchell's civilian awards | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Military societies

General Mitchell belonged to the following military societies and veteran organizations –

- Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States

- Military Order of Foreign Wars

- Military Order of the Carabao

- National Society of the Army of the Philippines (Merged with the Veterans of Foreign Service to form the Veterans of Foreign Wars in 1914.)

- American Legion

Dates of promotion

Note – the date listed is the date the promotion was accepted by General Mitchell. The actual date of rank was usually a few days earlier. (Source – Army Register, 1926. pg. 423.)

| No pin insignia in 1898 | Private, Volunteer Army: May 14, 1898 |

| No pin insignia in 1898 | Second Lieutenant, Volunteer Army: June 8, 1898 |

| First Lieutenant, Volunteer Army: March 4, 1899 | |

| No pin insignia in 1899 | Second Lieutenant, Volunteer Army: April 18, 1899 |

| First Lieutenant, Volunteer Army: June 11, 1900 | |

| First Lieutenant, Regular Army: April 26, 1901 | |

| Captain, Regular Army: March 2, 1903 | |

| Major, Regular Army: July 1, 1916 | |

| Lieutenant Colonel, Regular Army: May 15, 1917 | |

| Colonel, Temporary: October 10, 1917 | |

| Brigadier General, Temporary: October 14, 1918 | |

| Colonel, Regular Army: July 1, 1920 | |

| Brigadier General, Regular Army: July 16, 1920 | |

Posthumous recognition

Mitchell's uniforms on display at the National Museum of the United States Air Force |

B-25 Mitchell |

Mitchell family monument |

Obverse and reverse of the Air Force Combat Action Medal. |

Mitchell's concept of a battleship's vulnerability to air attack under "war-time conditions" would be vindicated after his death; a number of warships were sunk by air attack alone during World War II. The battleships Conte di Cavour, Arizona, Utah, Oklahoma, Prince of Wales, Roma, Musashi, Tirpitz, Yamato, Schleswig-Holstein, Lemnos, Kilkis, Marat, Ise and Hyūga were all put out of commission or destroyed by aerial attack including bombs, air-dropped torpedoes and missiles fired from aircraft. Some of these ships were destroyed by surprise attacks in harbor, others were sunk at sea after vigorous defense. However, most of the sinkings were carried out by aircraft carrier-based planes, not by land-based bombers as envisioned by Mitchell. The world's navies had responded quickly to the Ostfriesland lesson.[52][53][54]

William Sanders wrote the alternate history story "Billy Mitchell's Overt Act".[55] In the variant history depicted in the story, Mitchell managed to avoid the court-martial, and was still alive as an active service general in 1941. Being stationed in Hawaii, Mitchell correctly guessed the Japanese intentions and launched a preemptive strike on the oncoming Japanese carriers, and at the cost of his own life, several carriers were destroyed and disabled which prevented the Japanese Attack on Pearl Harbor.

- 1941: The North American B-25 Mitchell bomber, introduced in 1941, was named for Mitchell. Nearly 10,000 B-25s were produced, including the sixteen bombers which Lt. Colonel Jimmy Doolittle and his raiders used to bomb Tokyo and four other Japanese targets in April 1942.

- 1942: President Franklin Roosevelt, in recognizing Mitchell's contributions to air power, elevated him to the rank of major general (two stars) on the Army Air Corps retired list and petitioned the U.S. Congress to posthumously award Mitchell the Congressional Gold Medal, "in recognition of his outstanding pioneer service and foresight in the field of American military aviation." It was awarded in 1946.

- 1943: Walt Disney produced a film, "Victory Through Air Power", which opened with a filmed quote from General Mitchell, and is dedicated to him. The movie is based on a book by Major Alexander P. de Seversky, and is an explanation of how long range bombing and concentration of air power could shorten World War II, explaining the logistics and strategies that would give the Allies the upper hand at that time, as the Axis would be unable to develop similar aircraft and strategies due to their own issues. This film was shown to British Prime Minister Winston Churchill and U.S. President Franklin Roosevelt at a conference in Quebec, and reportedly made an impact on the planning and production of U.S. war material at the insistence of Roosevelt.[56]

- The unnamed "General" in the classic World War II movie A Guy Named Joe who gives the deceased pilot his new assignment, was "probably modeled after Billy Mitchell."[57]

- 1944: The United States Navy named a troop transport as the USS General William Mitchell (AP-114).

- 1951: The Billy Mitchell Drill Team (BMDT) was founded as an Air Force ROTC Drill Team; it is a drill, ceremony and color guard team at the University of Florida.[58]

- 1955: The Air Force Association passed a resolution calling for the voiding of Mitchell's court-martial. The Association named their Institute for Airpower Studies for the General; the current Dean of the Mitchell Institute is Lt. Gen. David A. Deptula, U.S.A.F. (Ret.).

- The motion picture The Court-Martial of Billy Mitchell, directed by Otto Preminger and starring Gary Cooper, portrays Mitchell's plight in a dramatic light.

- 1966: Mitchell was inducted into the National Aviation Hall of Fame.[59]

- 1968: The United States Board on Geographic Names officially named Mount Billy Mitchell in the Chugach Mountains, near the city of Valdez in Southcentral Alaska. This was in recognition of his central role in overseeing the construction of the Washington-Alaska Military Cable and Telegraph System (WAMCATS) while he was stationed in the District of Alaska from 1900–1904.[60]

- 1971: Pipes and Drums, the Billy Mitchell Scottish,[61] was created in Milwaukee to honor Mitchell and his ties to Scotland and Milwaukee.

- General Mitchell International Airport (has the Mitchell Gallery of Flight museum),[62] in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, is named after him as is the much smaller Billy Mitchell Airport in Cape Hatteras, North Carolina.

- Mitchell Hall, the cadet dining facility at the United States Air Force Academy, was dedicated in honor of Mitchell in 1959.[63]

- William (Billy) Mitchell High School in Colorado Springs, Colorado, and Billy Mitchell Elementary School in Lawndale, California are named after him.

- General Mitchell was honored at George Washington University in Washington, D.C., by his alma mater with the naming of a large residence building, William Mitchell Hall.

- The Civil Air Patrol cadet program includes an award called the General Billy Mitchell Award, signifying the rank of Cadet 2nd Lieutenant, and completion of several tests and essays.

- The U.S. Air Force Pipe Band, which existed as a free-standing unit within the U.S. Air Force Band between 1960 and 1970, wore a tartan created in honor of Billy Mitchell.[64]

- 1999: General Mitchell's portrait was put on a U.S. postage stamp. Although the 55-cent stamp met an airmail rate and portrayed a figure important to the development of aviation, it was not marked or issued as an airmail stamp. It also met the two-ounce first-class rate in effect at the time.

- 2004: Congress voted to reauthorize the president to posthumously commission Mitchell as a major general in the Army, which the president did in 2005.

- 2006: On May 18, the U.S. Air Force unveiled two prototypes for new service dress uniforms, referencing the service's heritage. One, modeled on the United States Army Air Service uniform, was designated the "Billy Mitchell heritage coat" (the other was named for Hap Arnold).[65] Ironically, the Air Service (including Mitchell) campaigned persistently against the high-collar blouse, which was the Army's regulation uniform coat of the time, because of its chafing effect on pilots' necks. In 1924, they succeeded and adopted the "turned-down" collar style blouse shown as the "Hap Arnold" uniform.

- 2007: The Air Force established and awarded the first Air Force Combat Action Medal (s), which is based on the insignia[66] painted on Billy Mitchell's own aircraft he flew during World War I.[67]

References

Notes

- ↑ Ott, USAF, Lt Col William. "Maj Gen William "Billy" Mitchell: A Pyrrhic Promotion" (Winter 2006). Air and Space Power Journal.

Of course these so-called adversaries did not impede Mitchell's reception of a medal of honor, but the initial efforts to promote Mitchell posthumously did come to a standstill. Senator Bass explained his motivation for reintroducing the bill years later: "He [Mitchell] was the father of the modern Air Force. ... This should be done."

- ↑ This comment is quoted as "incompetency, criminal negligence, and almost treasonable administration by the War and Navy departments" from an interview given by Gen Mitchell in San Antonio, Texas and published in the New York Times according to "The Courtmartial of Billy Mitchell (1925)" in Footnotes to American History by Harold S. Sharp, The Scarecrow Press, Inc., Metuchen, N.J., 1977, pp. 430–433.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Colonel Phillip S. Meilinger, USAF. Maxwell AFB. American Airpower Biography: Billy Mitchell

- ↑ Phi Kappa Psi (1991). Grand Catalogue of the Phi Kappa Psi Fraternity (13th ed.). Publishing Concepts, Inc. 1991. pp. 278, 466.

- ↑ Miller, Roger G. (2004). Billy Mitchell: "Stormy Petrel of the Air". Office of Air Force History: Washington, D.C., pp. 3–5. The Act of July 18, 1914 creating the Aviation Section restricted aviation training to unmarried lieutenants under the age of 30.

- ↑ Mitchell Gallery of Flight

- ↑ Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum, SPAD XVI

- ↑ Official U.S.A.F. Photo

- ↑ Hakim, Joy (1995). A History of Us: War, Peace and all that Jazz. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-509514-6.

- 1 2 "Mitchell William" (PDF). Biographical Data on Air Force General Officers, 1917–1952. AFHRA (USAF). Retrieved November 14, 2010.

- ↑ U.S. Air Service, September 1920, Vol. 4, Number 2, p. 34

- ↑ Glines, Carroll V. The Compact History of the United States Air Force, p. 111. Hawthorn Books, 1973

- ↑ Hurley, Alfred (2006). Billy Mitchell: Crusader for Air Power, Indiana University Press, ISBN 0-253-20180-2, p. 47.

- ↑ Hurley (2006), pp. 45–48.

- ↑ Futrell, Robert F. (1989). Ideas, Concepts, Doctrine: Basic Thinking in the United States Air Force, 1907–1960, Air University Press, Maxwell Air Force Base, pp. 32–36.

- ↑ Greer, Thomas H. (1985). USAF Historical Study 89, The Development of Air Doctrine in the Army Air Arm, 1917–1941 (PDF). Maxwell Air Force Base: Center For Air Force History. Retrieved November 10, 2010., pp. 24–25.

- ↑ U.S. Centennial of Flight Commission: Billy Mitchell Sinks the Ships

- ↑ John T. Correll, "Billy Mitchell and the Battleships", AIR FORCE Magazine, June 2008, pp. 64–65.

- 1 2 Correll, "Billy Mitchell and the Battleships", p.66.

- ↑ Vice Admiral Alfred Wilkinson Johnson, USN Ret. The Naval Bombing Experiments Off the Virginia Capes June and July 1921 (1959)

- ↑ Correll, "Billy Mitchell and the Battleships", pp. 65–66.

- ↑ "The US Aerial Bombing Experiment on Ships" Flight, September 15, 1921, pp. 615–618

- 1 2 Correll, "Billy Mitchell and the Battleships", p. 67.

- 1 2 "Winged Defense," William Mitchell, Originally published by G.P. Putnam's Sons, New York and London, 1925. (ISBN 0-486-45318-9) Reissued by Dover Publications, Inc., New York, 2006.

- ↑ Vice Admiral Alfred Wilkinson Johnson, USN Ret. The Naval Bombing Experiments: Bombing Operations (1959) Archived January 14, 2009, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Reid, John Alden. "Bomb the Dread Noughts!" Air Classics, 2006.

- ↑ Roger Miller, "Billy Mitchell: Stormy Petrel of the Air", DIANE Publishing, 2009, p. 33

- ↑ Craven. The Army Air Forces in World War II (1959)

- ↑ Time magazine, 23 July 1923. Thunderbolts

- ↑ New York Times, July 11, 1921, p.1

- 1 2 Tate (1998), p. 18.

- ↑ Futrell (1985), p. 39.

- ↑ Christopher M. Finan (2007). From the Palmer Raids to the Patriot Act: A History of the Fight for Free Speech in America. Beacon Press. p. 27. ISBN 978-0-8070-4428-5. Retrieved 2011-03-25.

- ↑ Clayton D. Laurie, "The United States Army and the Return to Normalcy in Labor Dispute Interventions: The Case of the West Virginia Coal Mine Wars, 1920–1921", 50 West Virginia History 1–24, 1991.

- ↑ Mitchell quotation at Call Field Memorial Museum in Wichita Falls, Texas

- ↑ Mitchell, William L. "Strategical Aspect of the Pacific Problem" as quoted in Clodfelter, Mark A. , "Molding Air Power Convictions: Development and Legacy of William Mitchell's Strategic Thought", in Melinger,Phillip S. ed., The Paths of Heaven: The Evolution of Air Power Theory, Alabama, Air University Press, 1997, pp.79–114.

- ↑ Clodfelter, Mark A. "Molding Air Power Convictions: Development and Legacy of William Mitchell's Strategic Thought", in Melinger, p.92.

- ↑ Mitchell, William. Winged Defense: The Development and Possibilities of Modern Air Power—Economic and Military (Dover Publications, 2006), p. 119. ISBN 0-486-45318-9

- ↑ Hurley, Alfred F., "Billy Mitchell: Crusader for Air Power," p. 109.

- ↑ Tate, Dr. James P., Lt Col USAF, Retired (1998). The Army and Its Air Corps: Army Policy toward Aviation, 1919–1941. Air University Press. ISBN 0-16-061379-5.

- ↑ Time Magazine, 2 November 1925. The article was a catchall, reading: "Though not mentioned in these articles, all disorders and neglect; to the prejudice of good order and military discipline, all conduct of a nature to bring discredit upon the military service and all crimes or offenses not capital, of which persons subject to military law may be guilty, shall be taken cognizance of by a general or special or summary court martial, according to the nature and degree of the offense, and punished at the discretion of the court."

- 1 2 MacArthur 1964, p. 85.

- ↑ Goldstein, Richard (December 18, 1998). "Gen. H.H. Howze, 89, Dies; Proposed Copters as Cavalry". The New York Times. Retrieved April 12, 2009.

- ↑ Maksel 2009, p. 48.

- ↑ Maksel 2009, p. 49.

- ↑ James 1970, pp. 307–310.

- ↑ "Gen. William 'Billy' Mitchell House". Aviation: From Sand Dunes to Sonic Booms – A National Register of Historic Places Travel Itinerary. National Park Service. Retrieved January 1, 2012.

- ↑ Forest Home Cemetery. Self-Guided Historical Tour

- ↑ Patterson, Michael Robert. "John Lendrum Mitchell III, First Lieutenant, United States Army". Arlington Cemetery. Retrieved January 1, 2012.

- ↑ "A–F". Air Force Association of Canada. Retrieved January 1, 2012.

- ↑ U.S. Army Center of Military History. "Medal of Honor Recipients - Authorized by Special Acts of Congress". History.army.mil. Retrieved 2014-02-21.

- ↑ Miller, Nathan (1997). The U.S. Navy: a history. Naval Institute Press. p. 200. ISBN 1-55750-595-0.

'The lesson is that we must put planes on battleships and get aircraft carriers quickly', declared Rear Admiral William A. Moffett, an articulate spokesman for naval air power.

- ↑ Mets, David R. (2008). Airpower and Technology: Smart and Unmanned Weapons. Praeger Security International Series. ABC-CLIO. p. 15. ISBN 0-275-99314-0.

- ↑ McBride, William M. (April 19, 2001). "Technological Change and the U.S. Navy" (PDF). MIT Program XIII—A Centennial. MIT. Retrieved December 11, 2010.

- ↑ Among the stories in the anthology "Alternate Generals", edited by Harry Turtledove, Baen Books, 1998

- ↑ Lawrence, John S.; Jewett, Robert (2002). The Myth Of The American Superhero. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. p. 191. ISBN 0-8028-4911-3.

- ↑ Horton, Andrew; McDougal, Stuart Y. (1998). Play It Again, Sam: Retakes on Remakes. University of California Press. p. 127. ISBN 0-520-20593-6.

- ↑ "The Billy Mitchell Drill Team BMDT". GatorConnect. Retrieved June 30, 2014.

- ↑ "William "Billy" Mitchell". National Aviation Hall of Fame. Retrieved April 5, 2011.

- ↑ "Mount Billy Mitchell". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved July 25, 2012.

- ↑ The Billy Mitchell Scottish of Milwaukee WI. at www.billymitchellscottish.org

- ↑ Mitchell Gallery of Flight

- ↑ "Mitchell Hall". 10th Force Support Squadron, USAFA. Retrieved November 15, 2010.

- ↑ Wilkinson, Todd. "the United States Air Force Tartans". Scottish Tartans Museum. Retrieved November 15, 2010.

- ↑ New service dress prototypes pique interest at www.af.mil.

- ↑ Mitchell Gallery of Flight Retrieved April 24, 2016

- ↑ For Today's Air Force, a New Symbol of Valor by John Kelly, June 13, 2007. Washington Post, p. B03. Retrieved June 13, 2007.

Bibliography

- Borch, Fred L. "Lore of the Corps: The Trial by Court-Martial of Colonel William 'Billy' Mitchell". Army Lawyer, January 2012, pp. 1–5

- Cooke, James J. The U.S. Air Service in the Great War: 1917–1919. Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers, 1996. ISBN 0-275-94862-5.

- Cooke, James J. Billy Mitchell. Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 2002. ISBN 1588260828

- Davis, Burke. The Billy Mitchell Affair. New York: Random House, 1967. OCLC 369301

- Hurley, Alfred H. Billy Mitchell: Crusader for Air Power (revised edition). Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1975. ISBN 0-253-31203-5, ISBN 0-253-20180-2.

- Kennett, Lee. The First Air War, 1914–1918. New York: Free Press, 1991. ISBN 0-684-87120-3.

- Levine, Isaac Don. Mitchell Pioneer of Air Power Duell, Sloan and Pearce, New York, first edition, 1943. OCLC 254425324

- Maksel, Rebecca. "The Billy Mitchell Court-Martial". Air & Space, Vol. 24, No. 2, 46–49. Also online (as of June 28, 2009) at http://www.airspacemag.com/history-of-flight/The-Billy-Mitchell-Court-Martial.html.

- O'Neil, William D. Mitchell, Billy. American National Biography Online, Feb. 2000, Revised Oct. 2007. http://www.anb.org/articles/06/06-00441.html.

- O'Neil, William D. "Transformation, Billy Mitchell Style," Proceedings, U.S. Naval Institute 128, No. 3 (Mar 2002): 100-04. Also online at http://analysis.williamdoneil.com/Transformation%20Billy%20Mitchell%20Style%203-02.pdf

- Waller, Douglas C. A Question of Loyalty: Gen. Billy Mitchell and the Court-Martial That Gripped the Nation (2004) excerpt and text search

- Wildenberg, Thomas. "Billy Mitchell Takes on the Navy", Naval History (2013) 27#5

- Wildenberg, Thomas. Billy Mitchell's War with the Navy: The Interwar Rivalry Over Air Power. Naval Institute Press, 2013. ISBN 9780870210389

Primary sources

- Mitchell, William. Memoirs of World War I: From Start to Finish of Our Greatest War. New York: Random House, 1960.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to William Lendrum Mitchell. |

- "Court Martial", TIME Magazine, November 2, 1925

- "Court Martial", TIME Magazine, November 9, 1925

- "Guilty", TIME Magazine, December 28, 1925

- American Airpower Biography: Billy Mitchell

- "Billy Mitchell". Find a Grave. Retrieved June 20, 2010.

- The short film 15 AF HERITAGE – HIGH STRATEGY – BOMBER AND TANKERS TEAM (1980) is available for free download at the Internet Archive

- World War II Liberty Ship USS Billy Mitchell