Bandung Conference

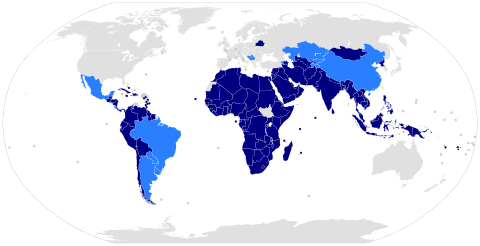

The first large-scale Asian–African or Afro–Asian Conference—also known as the Bandung Conference (Indonesian: Konferensi Asia-Afrika) —was a meeting of Asian and African states, most of which were newly independent, which took place on April 18–24, 1955 in Bandung, Indonesia. The twenty-nine countries that participated at the Bandung Conference represented nearly one-quarter of the Earth's land surface and a total population of 1.5 billion people.[1] The conference was organised by Indonesia, Burma, Pakistan, Ceylon (Sri Lanka), and India and was coordinated by Ruslan Abdulgani, secretary general of the Indonesian Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

The conference's stated aims were to promote Afro-Asian economic and cultural cooperation and to oppose colonialism or neocolonialism by any nation. The conference was an important step toward the Non-Aligned Movement.

Background

The conference of Bandung was preceded by the Bogor Conference (1949). This was the seed for the Colombo Plan and Bandung Conference. The 2nd Bogor Conference was held December 28–29, 1954.[2]

The conference reflected what the organisers regarded as a reluctance by the Western powers to consult with them on decisions affecting Asia in a setting of Cold War tensions; their concern over tension between the People's Republic of China and the United States; their desire to lay firmer foundations for China's peace relations with themselves and the West; their opposition to colonialism, especially French influence in North Africa and its colonial rule in Algeria; and Indonesia's desire to promote its case in the dispute with the Netherlands over western New Guinea (Irian Barat).

Sukarno, the first president of the Republic of Indonesia, portrayed himself as the leader of this group of states, which he later described as "NEFOS" (Newly Emerging Forces).[3] His daughter, Megawati Sukarnoputri has been head of the PDI-P party during both summit anniversaries, and the President of Indonesia Joko Widodo during the 3rd summit is a member of her party.

Plans for the conference were announced in December 1954.[4]

Anniversaries

- The 2nd Asian-African Conference Summit' took place in Jakarta and Bandung. The 2005 conference results in the NAWASILA (nine principles) and the establishment of the NAASP (New Asia-African Strategic Partnership). Of the 106 nations invited to the historic summit, 89 are represented by their heads of state or government or ministers.[2]

- The 3rd, or 60th Anniversary Conference Summit was held in Bandung and Jakarta from 21–25 April 2015, with the theme Strengthening South-South Cooperation to Promote World Peace and Prosperity. Delegates from 109 Asian and African countries, 16 observer countries and 25 international organizations participated.[2]

Discussion

Major debate centered around the question of whether Soviet policies in Eastern Europe and Central Asia should be censured along with Western colonialism. A consensus was reached in which "colonialism in all of its manifestations" was condemned, implicitly censuring the Soviet Union, as well as the West.[5] China played an important role in the conference and strengthened its relations with other Asian nations. Having survived an assassination attempt on the way to the conference, the Chinese premier, Zhou Enlai, displayed a moderate and conciliatory attitude that tended to quiet fears of some anticommunist delegates concerning China's intentions.

Later in the conference, Zhou Enlai signed on to the article in the concluding declaration stating that overseas Chinese owed primary loyalty to their home nation, rather than to China – a highly sensitive issue for both his Indonesian hosts and for several other participating countries. Zhou also signed an agreement on dual nationality with Indonesian foreign minister Sunario.

Declaration

A 10-point "declaration on promotion of world peace and cooperation," incorporating the principles of the United Nations Charter was adopted unanimously:

- Respect for fundamental human rights and for the purposes and principles of the charter of the United Nations

- Respect for the sovereignty and territorial integrity of all nations

- Recognition of the equality of all races and of the equality of all nations large and small

- Abstention from intervention or interference in the internal affairs of another country

- Respect for the right of each nation to defend itself, singly or collectively, in conformity with the charter of the United Nations

- (a) Abstention from the use of arrangements of collective defence to serve any particular interests of the big powers

(b) Abstention by any country from exerting pressures on other countries - Refraining from acts or threats of aggression or the use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any country

- Settlement of all international disputes by peaceful means, such as negotiation, conciliation, arbitration or judicial settlement as well as other peaceful means of the parties own choice, in conformity with the charter of the United Nations

- Promotion of mutual interests and cooperation

- Respect for justice and international obligations.[6]

The final Communique of the Conference underscored the need for developing countries to loosen their economic dependence on the leading industrialised nations by providing technical assistance to one another through the exchange of experts and technical assistance for developmental projects, as well as the exchange of technological know-how and the establishment of regional training and research institutes.

United States involvement

For the US, the Conference accentuated a central dilemma of its Cold War policy: by currying favor with Third World nations by claiming opposition to colonialism, it risked alienating its colonialist European allies.[7] The US security establishment also feared that the Conference would expand China's regional power.[8] In January 1955 the US formed a "Working Group on the Afro-Asian Conference" which included the Operations Coordinating Board (OCB), the Office of Intelligence Research (OIR), the Department of State, the Department of Defense, the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), and the United States Information Agency (USIA).[9] The OIR and USIA followed a course of "Image Management" for the US, using overt and covert propaganda to portray the US as friendly and to warn participants of the Communist menace.[10]

The United States, at the urging of Secretary of State John Foster Dulles, shunned the conference and was not officially represented. However, the administration issued a series of statements during the lead-up to the Conference. These suggested that the US would provide economic aid, and attempted to reframe the issue of colonialism as a threat by China and the Eastern Bloc.[11]

Representative Adam Clayton Powell, Jr. (D-N.Y.) attended the conference, sponsored by Ebony and Jet magazines instead of the U.S. government.[11] Powell spoke at some length in favor of American foreign policy there which assisted the United States's standing with the Non-Aligned. When Powell returned to the United States, he urged President Dwight D. Eisenhower and Congress to oppose colonialism and pay attention to the priorities of emerging Third World nations.[12]

African American author Richard Wright attended the conference with funding from the Congress for Cultural Freedom. Wright spent about three weeks in Indonesia, devoting a week to attending the conference and the rest of his time to interacting with Indonesian artists and intellectuals in preparation to write several articles and a book on his trip to Indonesia and attendance at the conference. Wright's essays on the trip appeared in several Congress for Cultural Freedom magazines, and his book on the trip was published as The Color Curtain: A Report on the Bandung Conference. Several of the artists and intellectuals with whom Wright interacted (including Mochtar Lubis, Asrul Sani, Sitor Situmorang, and Beb Vuyk) continued discussing Wright's visit after he left Indonesia.[13]

Outcome and legacy

The conference was followed by the Afro-Asian People's Solidarity Conference in Cairo[14] in September (1957) and the Belgrade Conference (1961), which led to the establishment of the Non-Aligned Movement.[15] In later years, conflicts between the nonaligned nations eroded the solidarity expressed at Bandung.

To mark the fiftieth anniversary of the Conference, Heads of State and Government of Asian-African countries attended a new Asian-African Summit from 20–24 April 2005 in Bandung and Jakarta. Some sessions of the new conference took place in Gedung Merdeka (Independence Building), the venue of the original conference. The conference concluded by establishing the New Asian–African Strategic Partnership (NAASP).[16]

The 2005 Asian African Summit yielded, inter-alia, the Declaration on the New Asian African Strategic Partnership (NAASP), the Joint Ministerial Statement on the New Asian African Strategic Partnership Plan of Action, and the Joint Asian African Leaders’ Statement on Tsunami, Earthquake and other Natural Disaster. The aforementioned declaration of NAASP is a manifestation of intra-regional bridge-building forming a new strategic partnership commitment between Asia and Africa, standing on three pillars, i.e. political solidarity, economic cooperation, and socio-cultural relations, within which governments, regional/sub-regional organizations, as well as peoples of Asian and African nations interact.

The 2005 Asian African Summit was attended by 106 countries, comprising 54 Asian countries and 52 African countries . The Summit concluded a follow-up mechanism for institutionalization process in the form of Summit concurrent with Business Summit every four years, Ministerial Meeting every two years, and Sectoral Ministerial as well as Technical Meeting if deemed necessary.

Participants

.svg.png) Kingdom of Afghanistan

Kingdom of Afghanistan.svg.png) Burma

Burma Kingdom of Cambodia

Kingdom of Cambodia.svg.png) Dominion of Ceylon

Dominion of Ceylon People's Republic of China

People's Republic of China.svg.png) Cyprus1

Cyprus1.svg.png) Republic of Egypt

Republic of Egypt.svg.png) Ethiopian Empire

Ethiopian Empire Gold Coast

Gold Coast India

India Indonesia

Indonesia.svg.png) Iran

Iran.svg.png) Kingdom of Iraq

Kingdom of Iraq Japan

Japan Jordan

Jordan.svg.png) Kingdom of Laos

Kingdom of Laos Lebanon

Lebanon Liberia

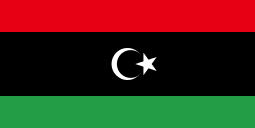

Liberia Kingdom of Libya

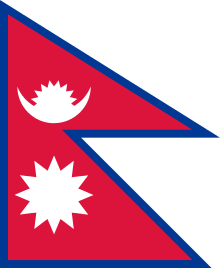

Kingdom of Libya Kingdom of Nepal

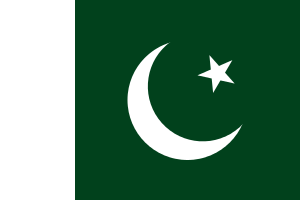

Kingdom of Nepal Dominion of Pakistan

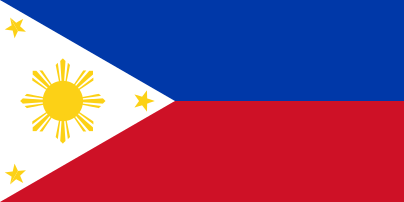

Dominion of Pakistan Philippines

Philippines.svg.png) Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia.svg.png) Syrian Republic

Syrian Republic.svg.png) Sudan

Sudan Thailand

Thailand Turkey

Turkey Democratic Republic of Vietnam

Democratic Republic of Vietnam State of Vietnam

State of Vietnam Mutawakkilite Kingdom of Yemen

Mutawakkilite Kingdom of Yemen

1 A pre-independent colonial Cyprus was represented by [the] eventual first president, Makarios III.[17]

Some nations were given "observer status". Such was the case of Brazil, who sent Ambassador Bezerra de Menezes.

See also

References

- ↑ Bandung Conference of 1955 and the resurgence of Asia and Africa, Daily News, Sri Lanka

- 1 2 3 http://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2015/04/23/asian-african-conference-timeline.html

- ↑ Cowie, H.R. (1993). Australia and Asia. A changing Relationship, 18.

- ↑ Parker, "Small Victory, Missed Chance" (2006), p. 156.

- ↑ Bandung Conference, at Encyclopædia Britannica

- ↑ Jayaprakash, N D (June 5, 2005). "India and the Bandung Conference of 1955 – II". People's Democracy - Weekly Organ of the Communist Party of India (Marxist). XXIX (23). Archived from the original on 11 March 2007. Retrieved 2007-02-07.

- ↑ Parker, "Small Victory, Missed Chance" (2006), p. 154. "... Bandung presented Washington with a geopolitical quandary. Holding the Cold War line against communism depended on the crumbling European empires. Yet U.S. support for that ancien régime was sure to earn the resentment of Third World nationalists fighting against colonial rule. The Eastern Bloc, facing no such guilt by association, thus did not face the choice Bandung presented to the United States: side with the rising Third World tide, or side with the shaky imperial structures damming it in."

- ↑ Parker, "Small Victory, Missed Chance" (2006), p. 155.

- ↑ Parker, "Small Victory, Missed Chance" (2006), pp. 157–158.

- ↑ Parker, "Small Victory, Missed Chance" (2006), p. 161. "An OCB memorandum of March 28 [...] recounts the efforts by OIR and the working group to distribute intelligence 'on Communist intentions, and [on] suggestions for countering Communist designs.' These were sent to U.S. posts overseas, with instructions to confer with invitee governments, and to brief friendly attendees. Among the latter, 'efforts will be made to exploit [the Bangkok message] through the Thai, Pakistani, and Philippine delegations.' Posts in Japan and Turkey would seek to do likewise. On the media front, the administration briefed members of the American press; '[this] appear[s] to have been instrumental in setting the public tone.' Arrangements had also been made for USIA coverage. In addition, the document refers to budding Anglo-American collaboration in the 'Image Management' effort surrounding Bandung."

- 1 2 Parker, "Small Victory, Missed Chance" (2006), p. 162.

- ↑ "Adam Clayton Powell Jr.". United States House of Representatives. Retrieved February 1, 2015.

- ↑ Roberts, Brian Russell (2013). Artistic Ambassadors: Literary and International Representation of the New Negro Era. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press. pp. 146–172. ISBN 0813933684.

- ↑ Mancall, Mark. 1984. China at the Center. p. 427

- ↑ Nazli Choucri, "The Nonalignment of Afro-Asian States: Policy, Perception, and Behaviour", Canadian Journal of Political Science / Revue canadienne de science politique, Vol. 2, No. 1.(Mar., 1969), pp. 1-17.

- ↑ "Seniors official meeting" (PDF). MFA of Indonesia. Retrieved 2012-10-01.

- ↑ Cyprus and the Non–Aligned Movement, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, (April, 2008)

Bibliography

- Parker, Jason C. "Small Victory, Missed Chance: The Eisenhower Administration, the Bandung Conference, and the Turning of the Cold War." In The Eisenhower Administration, the Third World, and the Globalization of the Cold War. Ed. Kathryn C. Statler & Andrew L. Johns. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2006. ISBN 0742553817

Further reading

- Asia-Africa Speaks From Bandung. Jakarta: Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Republic of Indonesia, 1955.

- Ampiah, Kweku. The Political and Moral Imperatives of the Bandung Conference of 1955 : the Reactions of the US, UK and Japan. Folkestone, UK : Global Oriental, 2007. ISBN 1-905246-40-4

- Kahin, George McTurnan. The Asian-African Conference: Bandung, Indonesia, April 1955. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1956.

- Lee, Christopher J., ed, Making a World After Empire: The Bandung Moment and Its Political Afterlives. Athens, OH: Ohio University Press, 2010. ISBN 978-0896802773

- Mackie, Jamie. Bandung 1955: Non-alignment and Afro-Asian Solidarity. Singapore: Editions Didier Millet, 2005. ISBN 981-4155-49-7

- Finnane, Antonia, and Derek McDougall, eds, Bandung 1955: Little Histories. Melbourne: Monash Asia Institute, 2010. ISBN 978-1-876924-73-7

External links

- Modern History Sourcebook: Prime Minister Nehru: Speech to Asian-African Conference Political Committee, 1955

- Modern History Sourcebook: President Sukarno of Indonesia: Speech at the Opening of the Asian-African Conference, 18 April 1955

- "Asian-African Conference: Communiqué; Excerpts" (PDF). Egyptian presidency website. 24 April 1955. Archived (PDF) from the original on 23 April 2011. Retrieved 23 April 2011.