Landlocked developing countries

Landlocked developing countries (LLDC) are developing countries that are landlocked.[1] The economic and other disadvantages experienced by such countries makes the majority of landlocked countries least developed countries (LDC), with inhabitants of these countries occupying the bottom billion tier of the world's population in terms of poverty.[2] Apart from Europe, there is not a single successful highly developed landlocked country when measured with the Human Development Index (HDI) and nine of the twelve countries with the lowest HDI scores are landlocked.[3][4] Landlocked European countries are exceptions in terms of development outcomes due to their close integration with the regional European market.[4] Landlocked countries that rely on transoceanic trade usually suffer a cost of trade that is double of their maritime neighbours.[5] Landlocked countries experience economic growth 6% less of their non-landlocked countries, holding other variables constant.[6]

UN-OHRLLS

The United Nations has an Office of the High Representative for the Least Developed Countries, Landlocked Developing Countries and Small Island Developing States (UN-OHRLLS). It mainly holds the view that high transport costs due to distance and terrain result in the erosion of competitive edge for exports from landlocked countries.[7] In addition, it recognizes the constraints on landlocked countries to be mainly physical, as in lack of direct access to the sea, isolation from world markets and high transit costs due to physical distance.[7] It also attributes geographic remoteness as one of the most significant reasons as why developing landlocked nations are unable to alleviate themselves while European landlocked cases are mostly developed because of short distances to the sea through well developed transient countries.[7] One other commonly cited factor is the administrative burdens associated with border crossings as there is a heavy load of bureaucratic procedures, paperwork, custom charges, and most importantly, traffic delay due to border wait times, which affect delivery contracts.[8] Delays and inefficiency compound geographically, where a 2 to 3 week wait due to border customs between Uganda and Kenya results in the impossibility of booking ships ahead of time in Mombasa, furthering delivery contract delays.[9] Despite these explanations, it is also important to consider the transit countries that neighbour LLDCs, in which goods of LLDCs are exported via the maritime ports of these countries.

Challenges with dependency

Although Adam Smith and traditional thought hold that geography and transportation are the culprits for keeping LLDCs from realizing development gains, Faye, Sachs and Snow hold the argument that no matter the advancement of infrastructure or lack of geographic distance to a port, landlocked nations are still dependent on their neighbouring transit nations.[10] Outlying this specific relationship of dependency, Faye et al. insist that though LLDCs vary across the board in terms of HDI index scores, LLDCs almost uniformly straddle at the bottom of HDI rankings in terms of region, suggesting a correlated dependency relationship of development for landlocked countries with their respective regions.[11] In fact, HDI levels decrease as one moves inland along the major transit route that runs from the coast of Kenya, across the country before going through Uganda, Rwanda and then finally Burundi.[11] Just recently, it has been economically modeled that if the economic size of a transit country is increased by just 1%, a subsequent increase of at least 2% is experienced by the landlocked country, which shows that there is hope for LLDCs if the conditions of their transit neighbours are addressed.[12] In fact, some LLDCs are seeing the brighter side of such a relationship, with the Central Asian nations geographic location between three BRIC nations (China, Russia and India) hungry for the region's oil and mineral wealth serving to boost economic development.[13] The three major factors that LLDCs are dependent on their transit neighbours are dependence on transit infrastructure, dependence on political relations with neighbours, and dependence on internal peace and stability within transit neighbours.[14]

A good case in point is Burundi. The country has relatively good internal road networks, but it cannot export its goods using the most direct route to sea since the inland infrastructure of Tanzania is poorly connected to the port of Dar es Salaam, reflecting issues of infrastructure dependency.[15] Meanwhile, though Burundi relies on Kenya’s port of Mombasa for export to circumnavigate Tanzania’s lack of infrastructure, this route was severed briefly in the 1990s when political relations fell with Kenya.[15] Finally, reflecting dependency on internal stability of transit neighbours, Burundi’s exports could not pass through Mozambique around the same time due to violent civil conflict.[8] Thus, Burundi had to export its goods using a route that stretched for 4500 km, crossing several borders and modal changes, to use the port of Durban in South Africa.[15] Other examples of landlocked dependency are the difficulties Mali faced in order to export its goods in the 1990s as nearly all its transit neighbours (Algeria, Togo, Ghana, Sierra Leone, Liberia, Guinea and Côte d'Ivoire) were effectively engaged in civil conflict around the same time[16] and the Central African Republic, where its travel routes for export depend on the season, as during the rainy season Cameroon’s roads are too poor to travel on and during the dry season the Democratic Republic of Congo’s Oubangui River water levels are poorly maintained for adequate maritime travel.[15]

The mineral resource rich countries of Central Asia and Mongolia offer a unique set of landlocked cases to explore for further depth, as these are nations where economic growth has grown exceptionally in recent years.[13] In Central Asia, oil and coal deposits have dictated development, where Kazakhstan’s GDI per capita in purchasing power parity was five times greater than Kyrgyzstan's in 2009.[13] Despite substantial development growth, these nations are not on a stable and destined path to being well developed, as the exploitation of their natural resources translates into an overall low average income and disparity, and because their limited deposits of resources mean only short term growth, and most importantly, because dependence on unprocessed materials increases the risks of experiencing shocks due to variations in market prices.[17] And though it is widely conceived that trade openness can allow for faster economic growth,[18] Mongolia is now subjected to a new geopolitical game for the flow of its railway lines between China and Russia.[19] Russian Railways now effectively owns 50% of Mongolia’s rail infrastructure, which could mean more efficient modernization and the laying of new rail lines, but really also translates into powerful leverage to pressure the government of Mongolia to concede to unfair terms for license grants of coal and copper-gold mines.[20] Thus, it can be argued that these nations with extraordinary mineral wealth should take the path of economic diversification.[17] All of these nations do not lack education qualifications as they are inheritors of the Soviet Union’s social education system, which means that poor economic policies are the culprit for more than 40% of the labour force being bogged down in the agricultural sector instead of being potentially funneled into secondary or tertiary economic activity.[17] Yet, it cannot be ignored that Mongolia benefits exceptionally due to its proximity to two giant BRIC nations, resulting in a rapid development of railway ports along its borders, especially along the Chinese border, as the Chinese seek to direct coking coal from Mongolia for China’s northwestern industrial core as well as for transportation to Japan and South Korea, resulting in revenue generation through the port of Tianjin.[19]

Furthermore, Nepal is another interesting example of a landlocked country with extreme dependency on its transit neighbour though India does not hold poor relations with Nepal, nor lack relative transport infrastructure or internal stability. In the 1970s, Nepal suffered from large commodity concentration and a high geographic centralization in its export trade as over 98% of its trade is restricted for export into India, and it 90% of its imports comes from India.[21] This Indian monopolization of trade with Nepal and a reliance on India for transoceanic trade resulted in a poor bargaining position for Nepal in the trade relationship.[21] In the 1950s, Nepal was forced to comply with India’s external tariffs as well as the prices of India’s exports.[21] This was problematic since the two countries have different levels of development, resulting in greater gains for the country that is more advanced and bigger in terms of resources and geographic size, that being India.[21] There was a fear that a parasitic dual relationship might emerge as well since India had the advantage of having a head start in industrialization, it dominated Nepal in manufacturing, which could reduce Nepal to being more of a supplier state of primary resources.[22] These problems, combined with the inability of Nepal to develop its own infant industries as it was unable to undersell its manufacturers in competition with Indian firms[23] resulted in subsequent treaties being drafted in 1960 and 1971, with amendments to the equal tariffs conditions, and terms of trade have since progressed.[24]

Almaty Ministerial Conference

In August, 2003, the International Ministerial Conference of Landlocked and Transit Developing Countries and Donor Countries on Transit Transport Cooperation (Almaty Ministerial Conference) was held in Almaty, Kazakhstan, setting the necessities of LLDCs in a universal document whereas there were no coordinated efforts on the global scale to serve the unique needs of LLDCs in the past.[5] Other than acknowledging the main forms of dependency that must be addressed, it also acknowledged the additional dependency issue where neighbouring transit countries are often observed to export the same products as their landlocked neighbours.[5] One result of the conference was a direct call for donor countries to step in to direct aid into setting up suitable infrastructure of transit countries to alleviate the burden of supporting LLDCs in regions of poor development in general.[5] The general objectives of the Almaty Program of Action is as follows:

- Reduce customs processes and fees to minimize costs and transport delays

- Improve infrastructure with respect to existing preferences of local transport modes, where road should be focused in Africa and rail in South Asia

- Implement preferences for landlocked countries’ commodities to boost their competitiveness in the international market

- To establish relationships between donor countries with landlocked and transit countries for technical, financial and policy improvements[25]

Current LLDCs

- Africa (16 countries)

Botswana

Botswana Burkina Faso[26]

Burkina Faso[26] Burundi[26]

Burundi[26] Central African Republic[26]

Central African Republic[26] Chad[26]

Chad[26] Ethiopia[26]

Ethiopia[26] Lesotho[26]

Lesotho[26] Malawi[26]

Malawi[26] Mali[26]

Mali[26] Niger[26]

Niger[26] Rwanda[26]

Rwanda[26] South Sudan

South Sudan Swaziland

Swaziland Uganda[26]

Uganda[26] Zambia[26]

Zambia[26] Zimbabwe

Zimbabwe

- Asia (10 countries)

Afghanistan[26]

Afghanistan[26] Bhutan[26]

Bhutan[26] Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan Kyrgyzstan

Kyrgyzstan Laos[26]

Laos[26] Mongolia

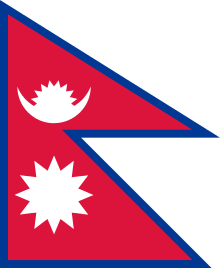

Mongolia Nepal[26]

Nepal[26] Tajikistan

Tajikistan Turkmenistan

Turkmenistan Uzbekistan

Uzbekistan

- Europe (4 countries)

- South America (2 countries)

See also

References

Notes

- ↑ http://www.unohrlls.org/en/lldc/31/

- ↑ Paudel. 2005, p. 2.

- ↑ Faye et al. 2004, p. 31-32.

- 1 2 Gallup, John Luke; Sachs, Jeffrey D.; Mellinger, Andrew D. (1999-08-01). "Geography and Economic Development". International Regional Science Review. 22 (2): 179–232. doi:10.1177/016001799761012334. ISSN 0160-0176.

- 1 2 3 4 Hagen. 2003, p. 13.

- ↑ Paudel. 2005, p. 11.

- 1 2 3 UN-OHRLLS. 2005.

- 1 2 Faye et al. 2004, p. 47.

- ↑ Faye et al. 2004, p. 48.

- ↑ Faye et al. 2004, p. 32.

- 1 2 Faye et al. 2004, p. 39.

- ↑ Paudel. 2012, p. 17.

- 1 2 3 Fara. 2012, p. 76.

- ↑ Faye et al. 2004, p. 40.

- 1 2 3 4 Faye et al. 2004, p. 44.

- ↑ Faye et al. 2004, p. 46-47.

- 1 2 3 Fara. 2012, p. 77.

- ↑ Paudel. 2012, p. 11.

- 1 2 Bulag. 2009, p. 100.

- ↑ Bulag. 2009, p. 101.

- 1 2 3 4 Jayaraman and Shrestha. 1976, p. 1114.

- ↑ Jayaraman and Shrestha. 1976, p. 1116-7.

- ↑ Jayaraman and Shrestha. 1976, p. 1117.

- ↑ Jayaraman and Shrestha. 1976, p. 1118.

- ↑ UN-OHRLLS. 2003.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 Also a Least Developed Country

Bibliography

- Bulag, U. E. (2010). Mongolia in 2009: From Landlocked to Land-linked Cosmopolitan. Asian Survey, 50(1), 97-103.

- Farra, F. (2012). OECD Presents… Unlocking Central Asia. Harvard International Review, 33(4), 76-79

- Faye, M. L., McArthur, J. W., Sachs, J. D., & Snow, T. (2004). The Challenges Facing Landlocked Developing Countries. Journal Of Human Development, 5(1), 31-68.

- Hagen, J. (2003). Trade Routes for Landlocked Countries. UN Chronicle, 40(4), 13-14.

- Jayaraman, T. K., Shrestha, O. L. (1976). Some Trade Problems of Landlocked Nepal. Asian Survey, 16(12), 1113-1123.

- Paudel R. C. (2012). Landlockedness and Economic Growth: New Evidence. Australian National University, Canberra, Australia.

- UN Office of the High Representative for the Least Developed Countries, Landlocked Developing Countries and Small Island Developing States. (2005). Landlocked Developing Countries. Retrieved from http://www.un.org/special-rep/ohrlls/lldc/default.htm

External links

- Office of the High Representative for the Landlocked Developing Countries, United Nations

- United Nations List of LLDCs