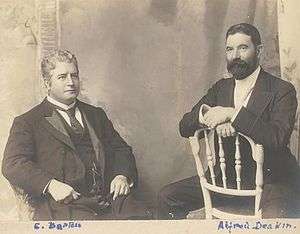

Alfred Deakin

| The Honourable Alfred Deakin | |

|---|---|

| |

| 2nd Prime Minister of Australia Elections: 1903, 1906, 1910 | |

|

In office 24 September 1903 – 27 April 1904 | |

| Governor-General |

Lord Tennyson Lord Northcote |

| Deputy | William Lyne |

| Monarch | Edward VII |

| Preceded by | Edmund Barton |

| Succeeded by | Chris Watson |

|

In office 5 July 1905 – 13 November 1908 | |

| Monarch | Edward VII |

| Governor-General |

Lord Northcote The Earl of Dudley |

| Deputy | William Lyne |

| Preceded by | George Reid |

| Succeeded by | Andrew Fisher |

|

In office 2 June 1909 – 29 April 1910 | |

| Monarch | Edward VII |

| Governor-General | The Earl of Dudley |

| Deputy | Joseph Cook |

| Preceded by | Andrew Fisher |

| Succeeded by | Andrew Fisher |

| Minister for External Affairs | |

|

In office 5 July 1905 – 13 November 1908 | |

| Prime Minister | Alfred Deakin |

| Preceded by | George Reid |

| Succeeded by | Lee Batchelor |

|

In office 24 September 1903 – 27 April 1904 | |

| Prime Minister | Alfred Deakin |

| Preceded by | Edmund Barton |

| Succeeded by | Billy Hughes |

| Leader of the Commonwealth Liberal Party | |

|

In office 26 May 1909 – 20 January 1913 | |

| Deputy | Joseph Cook |

| Succeeded by | Joseph Cook |

| Leader of the Protectionist Party | |

|

In office 24 September 1903 – 26 May 1909 | |

| Deputy |

William Lyne John Forrest |

| Preceded by | Edmund Barton |

| Succeeded by | Position Abolished |

| Attorney-General for Australia | |

|

In office 1 January 1901 – 24 September 1903 | |

| Prime Minister | Edmund Barton |

| Preceded by | Position Established |

| Succeeded by | James Drake |

| Leader of the Opposition | |

|

In office 1 July 1910 – 20 January 1913 | |

| Prime Minister | Andrew Fisher |

| Preceded by | Andrew Fisher |

| Succeeded by | Joseph Cook |

|

In office 26 May 1909 – 2 June 1909 | |

| Prime Minister | Andrew Fisher |

| Preceded by | Joseph Cook |

| Succeeded by | Andrew Fisher |

| Member of the Australian Parliament for Ballaarat | |

|

In office 30 March 1901 – 31 May 1913 | |

| Preceded by | Seat created |

| Succeeded by | Charles McGrath |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

3 August 1856 Melbourne, Victoria, British Empire |

| Died |

7 October 1919 (aged 63) Melbourne, Victoria, Australia |

| Nationality | British subject |

| Political party |

Protectionist Liberal |

| Spouse(s) | Patie Browne |

| Children | 3 |

| Education |

Melbourne Church of England Grammar School University of Melbourne |

| Religion | Australian Church |

Alfred Deakin (3 August 1856 – 7 October 1919) was a leader of the movement for Australian federation and later the second Prime Minister of Australia.[1] In the last quarter of the 19th century, Deakin was a major contributor to the establishment of liberal reforms in the colony of Victoria, including pro-worker industrial reforms. He also played a major part in establishing irrigation in Australia. It is likely that he could have been Premier of Victoria, but he chose to devote his energy to federation.

Throughout the 1890s Deakin was a participant in conferences of representatives of the Australian colonies that were established to draft a constitution for the proposed federation. He played an important role in ensuring that the draft was liberal and democratic and in achieving compromises to enable its eventual success. Between conferences, he worked to popularise the concept of federation and campaigned for its acceptance in colonial referenda. He then fought hard to ensure acceptance of the proposed constitution by the Government of the United Kingdom.

As Prime Minister, Deakin completed a significant legislative program that makes him, with Labor's Andrew Fisher, the founder of an effective Commonwealth government. He expanded the High Court, provided major funding for the purchase of ships, leading to the establishment of the Royal Australian Navy as a significant force under the Fisher government, and established Australian control of Papua. Confronted by the rising Australian Labor Party in 1909, he merged his Protectionist Party with Joseph Cook's Anti-Socialist Party to create the Commonwealth Liberal Party (known commonly as the Fusion), the main ancestor of the modern Liberal Party of Australia. The Deakin-led Liberal Party government lost to Fisher Labor at the 1910 election, which saw the first time a federal political party had been elected with a majority in either house in Federal Parliament. Deakin resigned from Parliament prior to the 1913 election, with Joseph Cook winning the Liberal Party leadership ballot.

Early life

Alfred was born on 3 August 1856. Alfred Deakin was the second child of English immigrants, William Deakin and his wife Sarah Bill, daughter of a Shropshire farmer, who had migrated to Australia in 1850 and settled in the Melbourne suburb of Collingwood in 1853. Deakin worked as a storekeeper, water-carter and general carrier and then became a partner in a coaching business and later manager of Cobb and Co in Victoria.[2][3]

Deakin was born at 90 George Street, Fitzroy, Melbourne,[4] and began his education at the age of four in a boarding school that was initially located at Kyneton, but later moved to the Melbourne suburb of South Yarra. In 1864 he became a day pupil at Melbourne Church of England Grammar School, but did not study seriously until his later school years, when he came under the influence of J. H. Thompson and the school's headmaster, John Edward Bromby, whose oratorical style Deakin admired and later partly adopted. In 1871 he graduated with good passes in history, algebra and Euclid and basic passes in English and Latin. He began evening classes in law at the University of Melbourne, while working as a schoolteacher and private tutor. He also spoke frequently at the University Debating Club founded by Charles Henry Pearson in 1874, read widely, dabbled in writing and became a lifelong spiritualist, holding the office of President of the Victorian Spiritualists' Union.[2][3][5]

Deakin graduated in 1877 and began practising as a barrister, but had difficulty in obtaining briefs. In May 1878, he met David Syme, the owner of the Melbourne daily The Age, who paid him to contribute reviews, leaders and articles on politics and literature. In 1880, he became editor of The Leader, The Age's weekly. During this period Syme converted him from supporting free trade to protectionism.[2][3] He became active in the Australian Natives' Association and began to practise vegetarianism.[6]

Victorian politics

Deakin stood for the largely rural seat of West Bourke in the Victorian Legislative Assembly in February 1879, as a supporter of Legislative Council reform, protection to encourage manufacturing and the introduction of a land tax to break up the big agricultural estates, and won by 79 votes. Due to a number of voters being disenfranchised by a shortage of voting papers, he used his maiden speech to announce his resignation; he lost the subsequent by-election by 15 votes, narrowly lost the seat in the February 1880 general election, but won it in yet another early general election in July 1880.[7] The radical Premier, Graham Berry, offered him the position of Attorney-General in August, but Deakin turned him down.[2][3]

In 1882, Deakin married Elizabeth Martha Anne ("Pattie") Browne, daughter of a well-known spiritualist. They lived with Deakin's parents until 1887, when they moved to "Llanarth", in Walsh Street, South Yarra. They had three daughters, Ivy, Stella and Vera by 1891.[8]

In 1883 Deakin became Commissioner for Public Works and Water Supply, and in 1884 he became Solicitor-General and Minister of Public Works. In 1885 Deakin secured the passage of the colony's pioneering Factories and Shops Act, enforcing regulation of employment conditions and hours of work.[8] In December 1884 he went to the United States to investigate irrigation, and presented a report in June 1885, Irrigation in Western America. Percival Serle described this report as "a remarkable piece of accurate observation, and was immediately reprinted by the United States government".[2] In June 1886, he introduced legislation to nationalise water rights and provide state-aid for irrigation works that helped establish irrigation in Australia.[3]

In 1885, Deakin became Chief Secretary and Commissioner for Water Supply and from 1890 Minister for Health and, briefly, Solicitor-General. In 1887 he led Victoria's delegation to the Imperial Conference in London, where he argued forcibly for reduced colonial payments for the defence provided by the British Navy and for improved consultation in relation to the New Hebrides. In 1889, he became the member for the Melbourne seat of Essendon and Flemington.[2][7][8]

In 1890 the government was brought down over its use of the militia to protect non-union labour during the maritime strike. In addition, Deakin lost his fortune and his father's fortune in the property crash of 1893, and had to return to the bar to restore his finances. In 1892, he unsuccessfully defended the mass murderer Frederick Bailey Deeming and assisted the defence in the 1893–94 libel trial of David Syme.[2][3]

Road to Federation

After 1890, Deakin refused all offers of cabinet posts and devoted his attention to the movement for federation. He was Victoria's delegate to the Australasian Federal Conference, convened by Sir Henry Parkes in Melbourne in 1890, which agreed to hold an intercolonial convention to draft a federal constitution. He was a leading negotiator at the Federal Conventions of 1891, which produced a draft constitution that contained much of the Constitution of Australia, as finally enacted in 1900. Deakin was also a delegate to the second Australasian Federal Convention, which opened in Adelaide in March 1897 and concluded in Melbourne in January 1898. He opposed conservative plans for the indirect election of senators, attempted to weaken the powers of the Senate, in particular seeking to prevent it from being able to defeat money bills, and supported wide taxation powers for the federal government.[3][8] Deakin often had to reconcile differences and find ways out of apparently impossible difficulties. Between and after these meetings, he travelled through the country addressing public meetings and he was partly responsible for the large majority in Victoria at each referendum.[2]

In 1900 Deakin travelled to London with Edmund Barton and Charles Kingston to oversee the passage of the federation bill through the Imperial Parliament, and took part in the negotiations with Joseph Chamberlain, the Colonial Secretary, who insisted on the right of appeal from the High Court to the Privy Council. Eventually a compromise was reached, under which constitutional (inter se) matters could be finalised in the High Court, but other matters could be appealed to the Privy Council.[3]

Deakin defined himself as an "independent Australian Briton," favouring a self-governing Australia but loyal to the British Empire. He certainly did not see federation as marking Australia's independence from Britain. On the contrary, Deakin was a supporter of closer empire unity, serving as president of the Victorian branch of the Imperial Federation League, a cause he believed to be a stepping stone to a more spiritual world unity.

Federal politics

In 1901 Deakin was elected to the first federal Parliament as MP for Ballaarat, and became Attorney-General in the ministry headed by Edmund Barton. He was active, especially in drafting bills for the Public Service, arbitration and the High Court. His second reading speech on the Immigration Restriction Bill to implement the White Australia Policy was notable in avoiding blatant racism by arguing that it was necessary to exclude the Japanese because of their good qualities, which would place them at an advantage over European Australians. His March 1902 speech in favour of the bill establishing the High Court of Australia helped overcome significant opposition to its establishment.[3]

First government 1903–04

When Barton retired to become one of the founding justices of the High Court, Deakin succeeded him as Prime Minister on 24 September 1903. His Protectionist Party did not have a majority in either House, and he held office only by courtesy of the Labor Party, which insisted on legislation more radical than Deakin was willing to accept. Deakin was the first PM to call an early election, within two months of becoming the leader, to catch his opponents off guard and take advantage of a large number of urban educated female voters who could cast a ballot for the first time.[9] In April 1904, he resigned without passing any legislation. The Labor leader Chris Watson and the Free Trade leader George Reid succeeded him, but neither could form a stable ministry.[3]

Second government 1905–08

Deakin resumed office in mid-1905, and retained it for three years. During this, the longest and most successful of his terms as Prime Minister, his government was responsible for much policy and legislation giving shape to the Commonwealth during its first decade, including bills to create an Australian currency. The Copyright Act was passed in 1905, the Bureau of Census and Statistics was established in 1906, Bureau of Meteorology was established in 1908 and the Quarantine Act was passed in 1908.[10]

In 1906 Deakin's government amended the Judiciary Act to increase the size of the High Court to five judges, as envisaged in the constitution, and appointed Isaac Isaacs and H. B. Higgins to fill the two additional seats. The first protective Federal tariff, the Australian Industries Protection Act was passed. This "New Protection" measure attempted to force companies to pay fair wages by setting conditions for tariff protection, although the Commonwealth had no powers over wages and prices.[3][10]

The Papua Act of 1905 established an Australian administration for the former British New Guinea and Deakin appointed Hubert Murray as Lieutenant-Governor of Papua in 1908, who ruled it for a 32-year period as a benevolent paternalist. His government passed a bill for the transfer of control of the Northern Territory from South Australia to the Commonwealth, which became effective in 1911.[3][10]

In December 1907, he introduced the first bill to establish compulsory military service, which was also strongly supported by Labor's Watson and Billy Hughes. He had long opposed the naval agreements to fund Royal Navy protection of Australia although Barton had agreed in 1902 that the Commonwealth would take over such funding from the colonies. In 1906 he announced that Australia would purchase destroyers, and in 1907 travelled to an Imperial Conference in London to discuss the issue, without success. In 1908 he invited Theodore Roosevelt's Great White Fleet to visit Australia, in a symbolic act of independence from Britain. The Surplus Revenue Act of 1908 provided £250,000 for naval expenditure, although these funds were first applied by the Andrew Fisher Labor government, creating the first independent navy in the British empire.[3][10]

Third government 1909–10

In 1908, Deakin was again forced from office by Labor. He then formed a coalition, the "Fusion", with his old conservative opponent George Reid, and returned to power in May 1909 at the head of Australia's first majority government. The Fusion was seen by many as a betrayal of Deakin's liberal principles, and he was called a "Judas" by Sir William Lyne. He ordered the dreadnought battle cruiser, Australia and established the financial agreement of 1909, which gave the States annual grants of 25 shillings ($2.50) per person, which was the basis of Commonwealth-state financial arrangements until 1927. In the April 1910 election his party was soundly defeated by Labor under Andrew Fisher.[3]

Retirement from politics

Deakin retired from Parliament in April 1913. He chaired the 1914 Royal Commission on Food Supplies and on Trade and Industry.[11] He was president of the Australian Commission for the Panama-Pacific International Exposition held in San Francisco in 1915 to celebrate the opening of the Panama Canal, but found his duties difficult because of severe progressive memory loss (due to dementia).[12] He was the only Australian Prime Minister to reject the title of 'Right Honourable'.[13]

He became an invalid and died in 1919 of meningoencephalitis aged only 63.[3][14] He is buried in the St Kilda Cemetery, alongside his wife, Pattie Deakin (b.1863, m.1882, d.1934).[15][16]

Journalism

Deakin continued to write prolifically throughout his career. He was a member of the Eclectic Association, fellow members included authors Theodore Fink, Arthur Topp, Arthur Patchett Martin and David Mickle.[17] Deakin wrote anonymous political commentaries for the London Morning Post even while he was Prime Minister. His account of the federation movement appeared as The Federal Story in 1944 and is a vital primary source for this history. His account of his career in Victorian politics in the 1880s was published as The Crisis in Victorian Politics in 1957. His collected journalism was published as Federated Australia in 1968.[3]

Spirituality

He was active in the Theosophical Society until 1896, when he resigned on joining the Australian Church, led by Charles Strong.[18]

Though Deakin always took pains to obscure the spiritual dimensions of his character from public gaze, he felt a strong sense of providence and destiny working in his career.[19] Like Dag Hammarskjöld much later, Deakin's sincere longing for spiritual fulfillment led him to express a sense of unworthiness in his private diaries, which mingled with his literary aspirations as a poet.[20]

His private prayer diaries, like those of Samuel Johnson, express a profound contemplative (though more ecumenical) Christian view of the importance of humility in seeking divine assistance with his career.[21] "A life, the life of Christ," Deakin wrote, "that is the one thing needful—the only revelation required is there.... We have but to live it."[22] In 1888, as an example relevant to his work for Federation, Deakin prayed: "Oh God, grant me that judgment & forsight which will enable me to serve my country—guide me and strengthen me, so that I may follow & persuade others to follow the path which shall lead to the elevation of national life & thought & permanence of well earned prosperity—give me light & truth & influence for the highest & the highest only."[23] As Walter Murdoch pointed out, "[Deakin] believed himself to be inspired, and to have a divine message and mission."[24]

Historian Manning Clark, whose History of Australia cites extensively from his studies of Deakin's private diaries in the National Library of Australia, wrote: "By reading the world's scriptures and mystics a deep peace had settled far inside [Deakin]: now he felt a 'serenity at the core of my heart.' He wanted to know whether participation in the world's affairs would disturb that serenity... he was tormented by the thought that the emptiness of the man within corresponded with the emptiness of society at large where Mammon had found a new demesne to infest."[25]

Legacy

Deakin was almost universally liked, admired and respected by his contemporaries, who called him "Affable Alfred." He made his only real enemies at the time of the Fusion, when not only Labor but also some liberals such as Sir William Lyne reviled him as a traitor.[3]

Deakin had a long and happy marriage and was survived by his wife and their three daughters:

- Ivy (1883–1970) married Herbert Brookes.

- Alfred Deakin Brookes (1920-2005) - the first head of the Australian Secret Intelligence Service

- Stella (1886–1976) married Sir David Rivett.

- Vera (1891–1978) married Sir Thomas White.

His descendants are still active in Melbourne political and business circles and he is regarded as a founding father by the modern Liberal Party. The Division of Deakin, Alfred Deakin High School, Deakin University, Deakin Avenue in the rural city of Mildura, Deakin Hall at Monash University, Deakin House at Melbourne Grammar School and the Canberra suburb of Deakin are named after him.

In 1969, Australia Post honoured him on a postage stamp bearing his portrait.[26]

See also

- First Deakin Ministry

- Second Deakin Ministry

- Third Deakin Ministry

- Fourth Deakin Ministry

- List of Prime Ministers of Australia

- Deakin University

References

- ↑ "Senators and Members". Parliament of Australia.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Serle, Percival. "Deakin, Alfred (1856–1919)". Dictionary of Australian Biography. Project Gutenberg Australia. Archived from the original on 14 February 2010. Retrieved 8 February 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 Norris, R. (1981). "Deakin, Alfred (1856–1919)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Canberra: Australian National University. Retrieved 2 October 2013.

- ↑ "Photograph, 90 George Street, Fitzroy". Picture Victoria. Retrieved 8 February 2010.

- ↑ "Alfred Deakin" (PDF). Prime Facts. Australian Prime Ministers Centre. Retrieved 8 February 2010.

- ↑ "Cheap Livers and Death Dodgers: Vegetarianism in the National Library" (PDF). NLA News. XIV (3). December 2003. Retrieved 8 February 2010.

- 1 2 "Alfred Deakin". re-member. Parliament of Victoria. Retrieved 8 February 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 "Alfred Deakin, before". Australia's Prime Ministers. National Archives of Australia. Retrieved 8 February 2010.

- ↑ Julian Fitzgerald On Message: Political Communications of Australian Prime Ministers 1901 - 2014 Clareville Press 2014 p 39

- 1 2 3 4 "Alfred Deakin, in office". Australia's Prime Ministers. National Archives of Australia. Retrieved 8 February 2010.

- ↑ National Archives of Australia: Alfted Deakin, Fact Sheet 211

- ↑ ABC Australia: Federation - Episode 3

- ↑ "National Archives of Australia Fast Facts of Australian PMs". National Archives of Australia. Retrieved 31 October 2014.

- ↑ "Alfred Deakin, afterwards". Australia's Prime Ministers. National Archives of Australia. Retrieved 8 February 2010.

- ↑ "The Visionary: Alfred Deakin (1856-1919)". St Kilda Biographies. Friends of St Kilda Cemetery. Retrieved 2 January 2014.

- ↑ "DEATH OF ALFRED DEAKIN-FUNERAL OF GENERAL BOTHA.". Sydney Mail (NSW : 1912 - 1938). NSW: National Library of Australia. 15 October 1919. p. 8. Retrieved 31 October 2014.

- ↑ Eastwood, Jill. "Topp, Arthur Manning (1844–1916)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Canberra: Australian National University. Retrieved 2 October 2013.

- ↑ "Alfred Deakin". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Retrieved 21 March 2013.

- ↑ Al Gaby. The Mystic Life of Alfred Deakin. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1992. p 2.

- ↑ Al Gaby. The Mystic Life of Alfred Deakin. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1992. p 37.

- ↑ Samuel Johnson. Doctor Johnson's Prayers Elton Trueblood (ed) SCM Press. London 1947.

- ↑ JA La Nauze. Alfred Deakin. A Biography. Angus and Robertson. Melbourne. p 79.

- ↑ Al Gaby. The Mystic Life of Alfred Deakin. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 1992. p 76 citing Deakin's Boke of Praer and Prase Prayer XLVII 12 August 1888

- ↑ Walter Murdoch. Alfred Deakin: A sketch. Constable &Co Ltd. London 1923 p 137.

- ↑ CMH Clark. A History Of Australia. Volume V. The People Make Laws 1888–1915. Melbourne University Press. Melbourne. 1981. pp302 and 275

- ↑ "Stamp". Australian Stamp and Coin Company. Retrieved 8 February 2010.

Bibliography

- 1974 - Deakin, Alfred and Murdoch, Walter / La Nauze, J A and Nurser, Elizabeth (eds) "Walter Murdoch and Alfred Deakin on 'Books and Men': Letters and Comments, 1900–1918" Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1974. ISBN 0-522-84056-6

- 1968 - Deakin, Alfred / La Nauze, J A (ed) "Federated Australia: Selections from Letters to the Morning Post 1900–1910" Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1968.

- 1957 - Deakin, Alfred / La Nauze, J A and Crawford, R M (eds) "The Crisis in Victorian Politics, 1879–1881" Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, 1957.

- 1944 - Deakin, Alfred / Brookes, Herbert (ed) "The Federal Story: The Inner History of the Federal Cause" Robertson & Mullens, Melbourne, 1944 (later editions edited by J.A. La Nauze [1963] and Stuart Macintyre [1995]).

- 1893 - Deakin, Alfred "Temple and Tomb in India" Melville, Mullen and Slade, Melbourne, 1893.

- 1893 - Deakin, Alfred "Irrigated India: An Australian View of India and Ceylon, Their Irrigation and Agriculture" W. Thacker & Co., London, 1893.

- 1885 - Deakin, Alfred "Irrigation in Western America, so Far as it has Relation to the Circumstances of Victoria" Government Printer, Melbourne, 1885.

- 1877 - Deakin, Alfred "A New Pilgrim's Progress" Terry, Melbourne, 1877.

- 1875 - Deakin, Alfred "Quentin Massys: A Drama in Five Acts" J.P. Donaldson, Melbourne, 1875.

Further reading

- Birrell, Robert (1995), A Nation of Our Own, Longman Australia, Melbourne. ISBN 0-582-87549-8

- Gabay, Al (1992), The Mystic Life of Alfred Deakin, Cambridge University Press.

- Hughes, Colin A (1976), Mr Prime Minister. Australian Prime Ministers 1901–1972, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, Victoria, Ch.22. ISBN 0-19-550471-2

- La Nauze, John A (1965), Alfred Deakin: A Biography, two volumes, Melbourne University Press, Carlton, Victoria.

- Mennell, Philip (1892). "

Deakin, Hon. Alfred". The Dictionary of Australasian Biography. London: Hutchinson & Co. Wikisource

Deakin, Hon. Alfred". The Dictionary of Australasian Biography. London: Hutchinson & Co. Wikisource - Deakin, Alfred (1944). The Federal Story: The Inner History of the Federal Cause. Robertson and Mullins.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Alfred Deakin. |

- Alfred Deakin – Australia's Prime Ministers / National Archives of Australia

- Guide to the papers of Alfred Deakin held and selectively digitised by the National Library of Australia

- Alfred Deakin Prime Ministerial Library

- Deakin University

- Alfred Deakin's personal library on LibraryThing