Robert Menzies

| The Right Honourable Sir Robert Menzies KT, AK, CH, FAA, FRS, QC | |

|---|---|

| |

| 12th Prime Minister of Australia Elections: 1940, 1946, 1949, 1951, 1954, 1955, 1958, 1961, 1963 | |

|

In office 26 April 1939 – 29 August 1941 | |

| Monarch | George VI |

| Governor-General | Lord Gowrie |

| Deputy |

Earle Page Archie Cameron Arthur Fadden |

| Preceded by | Earle Page |

| Succeeded by | Arthur Fadden |

|

In office 19 December 1949 – 26 January 1966 | |

| Monarch |

George VI Elizabeth II |

| Governor-General |

Sir William McKell Sir William Slim Viscount Dunrossil Viscount De L'Isle Lord Casey |

| Deputy |

Arthur Fadden John McEwen |

| Preceded by | Ben Chifley |

| Succeeded by | Harold Holt |

| Leader of the Liberal Party | |

|

In office 31 August 1945 – 26 January 1966 | |

| Deputy |

Eric Harrison Harold Holt |

| Preceded by | Position Established |

| Succeeded by | Harold Holt |

| Leader of the United Australia Party | |

|

In office 26 April 1939 – 29 August 1941 | |

| Preceded by | Joseph Lyons |

| Succeeded by | Billy Hughes |

|

In office 23 September 1943 – 31 August 1945 | |

| Deputy | Eric Harrison |

| Preceded by | Billy Hughes |

| Succeeded by | Position Abolished |

| Leader of the Opposition | |

|

In office 23 September 1943 – 19 December 1949 | |

| Prime Minister |

John Curtin Frank Forde Ben Chifley |

| Deputy | Arthur Fadden |

| Preceded by | Arthur Fadden |

| Succeeded by | Ben Chifley |

| Member of the Australian Parliament for Kooyong | |

|

In office 15 September 1934 – 16 February 1966 | |

| Preceded by | John Latham |

| Succeeded by | Andrew Peacock |

| Deputy Premier of Victoria | |

|

In office 19 May 1932 – 24 July 1934 | |

| Premier | Sir Stanley Argyle |

| Preceded by | Albert Dunstan |

| Succeeded by | Wilfrid Kent Hughes |

| Attorney-General of Victoria | |

|

In office 19 May 1932 – 24 July 1934 | |

| Premier | Sir Stanley Argyle |

| Preceded by | Ian Macfarlan |

| Succeeded by | Albert Bussau |

| Member of the Victorian Legislative Assembly for Nunawading | |

|

In office 30 November 1929 – 31 August 1934 | |

| Preceded by | Edmund Greenwood |

| Succeeded by | William Boyland |

| Member of the Victorian Legislative Council for East Yarra Province | |

|

In office 2 June 1928 – 11 November 1929 | |

| Preceded by | George Swinburne |

| Succeeded by | Clifden Eager |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Robert Gordon Menzies 20 December 1894 Jeparit, Colony of Victoria, Australia |

| Died |

15 May 1978 (aged 83) Malvern, Victoria, Australia |

| Political party |

Nationalist Party of Australia (1928–1931) United Australia Party (1931–1945) Liberal Party of Australia (1945–1966) |

| Spouse(s) | Dame Pattie Menzies (née Leckie) |

| Children | 3 |

| Parents | James Menzies |

| Education |

Wesley College, Melbourne University of Melbourne |

| Profession | Lawyer |

| Religion | Presbyterianism[1] |

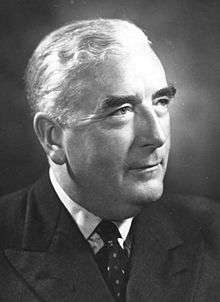

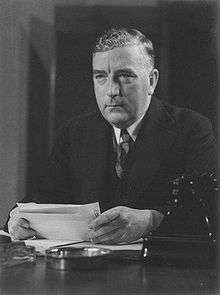

Sir Robert Gordon Menzies, KT, AK, CH, PC, QC, FAA, FRS (20 December 1894 – 15 May 1978), was the Prime Minister of Australia from 1939 to 1941 and again from 1949 to 1966. He is Australia's longest-serving prime minister, serving over 18 years in total.

Menzies studied law at the University of Melbourne and became one of Melbourne's leading lawyers. He was Deputy Premier of Victoria from 1932 to 1934, and then transferred to federal parliament, subsequently becoming Attorney-General and Minister for Industry in the government Joseph Lyons. In April 1939, following Lyons' death, Menzies was elected leader of the United Australia Party (UAP) and sworn in as prime minister. He authorised Australia's entry into World War II in September 1939, and in 1941 spent four months in England to participate in meetings of Churchill's war cabinet. On his return to Australia in August 1941, Menzies found that he had lost the support of his party and consequently resigned as prime minister. He subsequently helped to create the new Liberal Party, and was elected its inaugural leader in August 1945.

At the 1949 federal election, Menzies led the Liberal–Country coalition to victory and returned as prime minister. His appeal to the home and family, promoted via reassuring radio talks, matched the national mood as the economy grew and middle-class values prevailed, and the Labor Party's support had also been eroded by Cold War scares. After 1955, his government also received support from the Democratic Labor Party, a breakaway group from the Labor Party. Menzies won seven consecutive elections during his second term, eventually retiring as prime minister in January 1966. His legacy has been debated, but his government is remembered today for its development of Canberra (the national capital), its expanded post-war immigration scheme, its emphasis on higher education, and its national security policies, which saw Australia contribute troops to the Korean War, the Malayan Emergency, the Indonesia–Malaysia confrontation, and the Vietnam War.

Early life

Robert Gordon Menzies was born to James Menzies and Kate (née Sampson) in Jeparit, a town in the Wimmera region of northwestern Victoria, on 20 December 1894.[2] He was the fourth of six children, with one sister and three brothers.[3] His father James was a storekeeper and held agencies for farm machinery and stock agents,[4] the son of Scottish crofters who had immigrated to Australia in the mid-1850s in the wake of the Victorian gold rush. His maternal grandfather, John Sampson, was a Cornish miner from Penzance who also came to seek his fortune on the goldfields, in Ballarat.[5] His father was elected to the Victorian State Parliament for the seat of Lowan in 1911 and moved with the family to Melbourne after selling the farm.[4] One of his uncles, Hugh Menzies, had been a member of the Victorian Parliament for Stawell for two years up to 1904, while another uncle, Sydney Sampson, had represented the Division of Wimmera in the House of Representatives. His cousin, Sir Douglas Menzies, became a justice of the High Court of Australia[3] He was proud of his Highland ancestry – his enduring nickname, Ming, came from /ˈmɪŋəs/, the Scots – and his own preferred – pronunciation of Menzies. His middle name, Gordon, was given to him in honour and memory of Charles George Gordon, a British general killed in Khartoum in 1885.[6]

Menzies's formal education began at Humffray Street State School in Bakery Hill, Ballarat,[7] then later at private school in Ballarat. He attended Wesley College in Melbourne and studied law at the University of Melbourne, graduating in 1916.

When World War I began, Menzies was 19 years old and held a commission in the university's militia unit. He resigned his commission at the very time others of his age and class clamoured to enlist.[3] It was later stated that, since the family had made enough of a sacrifice to the war with the enlistment of two of three eligible brothers, Menzies should stay to finish his studies.[3] Menzies himself never explained the reason why he chose not to enlist. It should be noted that the two brothers, James and Frank, who did enlist did not do so until 1915 after the landings at Anzac which belies the alleged reason.[8][9] Subsequently, he was prominent in undergraduate activities and won academic prizes and declared himself to be a patriotic supporter of the war and conscription.[10] In 1916 he became the editor of the Melbourne University Magazine (MUM), establishing a reputation as an unusually bright and articulate member of the undergraduate community.[11]

Legal career

After graduating from the University of Melbourne in 1916 with First Class Honours in Law, Menzies was admitted to the Victorian Bar and to the High Court of Australia in 1918. Establishing his own practice in Melbourne, Menzies specialised chiefly in Constitutional law which he had read with the leading Victorian jurist and future High Court judge, Sir Owen Dixon.[12] In 1920 Menzies served as an advocate for the Amalgamated Society of Engineers which eventually took its appeal to the High Court of Australia.[12] The case became a landmark authority for the positive reinterpretation of Commonwealth powers over those of the States. The High Court's verdict raised Menzies's profile as a skilled advocate and eventually he was appointed a King's Counsel in 1929.

Personal life

On 27 September 1920, Menzies married Pattie Leckie (1899–1995) at Kew Presbyterian Church in Melbourne. Pattie Leckie was the eldest daughter of John Leckie, a Deakinite Liberal who was elected the member for Benambra in the Victorian Legislative Assembly in 1913. Soon after their marriage, the Menzies bought the house in Howard Street, Kew, which would become their family home for 25 years. They had three surviving children: Kenneth (1922–1993), Robert Jr (known by his middle name, Ian; 1923–1974)[13] and a daughter, Margery (known by her middle name, Heather; born 1928).[14] Another child died at birth.

Kenneth was born in Hawthorn on 14 January 1922. He married Marjorie Cook on 16 September 1949,[15] and had six children; Alec, Lindsay, Robert III, Diana, Donald, and Geoffrey. He died in Kooyong on 8 September 1993.[16] Ian and Heather were both born in Kew, on 12 October 1923 and 3 August 1928, respectively. Ian was afflicted with an undisclosed illness for most of his life. He never married, nor had children, and died in 1974 in East Melbourne at the age of 50.[13] Heather married Peter Henderson, a diplomat and public servant (working at the Australian Embassy in Jakarta, Indonesia at the time of their marriage, and serving as the Secretary of the Department of Foreign Affairs from 1979 to 1984), on 1 May 1955. A daughter, Roberta, named for Menzies, was born in 1956. She was instrumental in the development of Canberra and the Australian Capital Territory, and lives in Canberra with her husband.[17]

Career in Victorian state politics, 1928–1934

In 1928, Menzies entered state parliament as a member of the Victorian Legislative Council from East Yarra Province, representing the Nationalist Party of Australia. He stood for constitutional democracy, the rule of law, the sanctity of contracts and the jealous preservation of existing institutions. Suspicious of the Labor Party, Menzies stressed the superiority of free enterprise except for certain public utilities such as the railways.[18] His candidacy was nearly defeated when a group of ex-servicemen attacked him in the press for not having enlisted, but he survived this crisis. Within weeks of his entry to parliament, he was made a minister without portfolio in a new minority Nationalist State government led by Premier William McPherson. The new government had formed when the previous Labor government lost the support of the cross-bench Country Progressives.[19] The following year he shifted to the Legislative Assembly as the member for Nunawading. In 1929, he founded the Young Nationalists as his party's youth wing and served as its first president. Holding the portfolios of Attorney-General and Minister for the Railways, Menzies served as Deputy Premier of Victoria from May 1932 until July 1934.

Early career in federal politics, 1934–1939

Successfully contesting the Melbourne seat of Kooyong in the 1934 Federal election, Menzies transferred to federal politics representing the United Australia Party (UAP—the Nationalists had merged with other non-Labor groups to form the UAP during his tenure as a state parliamentarian). He was immediately appointed Attorney-General and Minister for Industry in the Lyons government. In 1937 he was appointed a Privy Counsellor. In late 1934 and early 1935 Menzies, then attorney-general, unsuccessfully prosecuted the government's highly controversial case for the attempted exclusion from Australia of Egon Kisch, a Czech Jewish communist.[20] The initial prohibition on Kisch's entry to Australia, however, had not been imposed by Menzies but by the Country Party minister for the interior Thomas Paterson.[21]

Menzies had extended discussions with British experts on Germany in 1935-35, but could not make up his mind whether Hitler was a "real German patriot" or a "mad swash-buckler." He expressed both views with an inclination to the former, says historian David Bird. In published essays in 1936 he called for a "live and let-live" attitude.[22]

In August 1938, while Attorney-General of Australia, Menzies spent several weeks on an official visit to Nazi Germany. He was strongly committed to democracy for the British peoples, but he initially thought that the Germans should take care of their own affairs. He strongly supported the appeasement policies of the Chamberlain government in London, and sincerely believed that war could and should be avoided at all costs.[23][24]

There is no doubt Menzies supported British foreign policy, including appeasement, and was initially reticent about the prospect of going to war with Germany. However, by September 1939 the unfolding crisis in Europe convinced him that the diplomatic efforts by Chamberlain and other leaders to broker a peace agreement had failed and that war was now an inevitability. In his Declaration of War broadcast on 3 September 1939, Menzies explained the dramatic turn of events over the past twelve months necessitating this change of course:

In those past 12 months, what has happened? in cold-blooded breach of the solemn obligations implied in both the statements I have quoted, Hitler has annexed the whole of the Czechoslovak state. Has, without flickering an eyelid, made a pact with Russia, a country the denouncing and reviling of which has been his chief stock-in-trade ever since he became chancellor. And has now, under circumstances which I will describe to you, invaded with armed force and in defiance of civilised opinion, the independent nation of Poland. Your own comments on this dreadful history will need no reinforcement by me. All I need say is, that whatever the inflamed ambitions of the German Führer may be, he will undoubtedly learn, as other great enemies of freedom have learned before, that no empire, no dominion, can be soundly established upon a basis of broken promises or dishonoured agreements.[25]

Menzies went on to say that if Hitler's expansionist "policy were allowed to go unchecked there could be no security in Europe and there could be no just peace for the world".[26]

Meanwhile, on the domestic front, animosity developed between Sir Earle Page and Menzies which was aggravated when Page became Acting Prime Minister during Lyons' illness after October 1938. Menzies and Page attacked each other publicly. He later became deputy leader of the UAP. His supporters said he was Lyons' natural successor; his critics accused Menzies of wanting to push Lyons out, a charge he denied. In 1938 his enemies ridiculed him as "Pig Iron Bob", the result of his industrial battle with waterside workers who refused to load scrap iron being sold to imperial Japan in the Dalfram dispute of 1938.[27] In 1939, however, he resigned from the Cabinet in protest at postponement of the national insurance scheme and insufficient expenditure on defence.

First term as prime minister, 1939–1941

With Lyons's sudden death on 7 April 1939, Page became caretaker prime minister until the UAP could elect a new leader. On 18 April 1939, Menzies was elected leader of the UAP and was sworn in as prime minister eight days later.

A crisis arose almost immediately, however, when Page refused to serve under him. In an extraordinary personal attack in the House, Page accused Menzies of cowardice for not having enlisted in the War, and of treachery to Lyons. Menzies then formed a minority government. When Page was deposed as Country Party leader a few months later, Menzies took the Country Party back into his government in a full-fledged Coalition, with Page's successor, Archie Cameron, as number-two-man in the government. On 3 September 1939 Britain and France declared war on Germany due to its invasion of Poland on 1 September, leading to the start of World War II.[17] Menzies responded immediately by also declaring Australia to be at war in support of Britain, and delivered a radio broadcast to the nation on that same day, which began "Fellow Australians. It is my melancholy duty to inform you officially that in consequence of a persistence by Germany in her invasion of Poland, Great Britain has declared war upon her and that, as a result, Australia is also at war."[18][19] A couple of days after the declaration, Menzies recalled parliament and asked for general support as the government faced the enormous responsibility of leading the nation in war time. Page and Curtin, as party leaders, pledged their support for all that needed to be done for the defense of the country.[11]

Thus Menzies at the age of 44 found himself a wartime leader of a small nation of 7 million people. He was especially worried about the military threat from Japan. Australia had very small forces, and depended on Britain for defence against the looming threat of the Japanese Empire, with its 100 million people, a very powerful Army and Navy and an aggressive foreign policy. Menzies hoped that a policy of appeasement would head off a war with Japan, and repeatedly pressured London.[28] Menzies did his best to rally the country, but the bitter memories of the disillusionment which followed World War I made his task difficult, this being compounded by Menzies's lack of a service record. Further, as attorney-general and deputy prime minister, Menzies had made an official visit to Germany in 1938, when the official policy of the Australian government, supported by the Opposition, was strong support for Neville Chamberlain's policy of Appeasement. He led the Coalition into the 1940 election and suffered an eight-seat swing, losing the slender majority he had inherited from Lyons. The result was a hung parliament, with the Coalition two seats short of a majority. Menzies managed to form a minority government with the support of two independent MPs, Arthur Coles and Alex Wilson. Labor, led by John Curtin, refused Menzies's offer to form a war coalition, and opposed using the Australian army for a European war, preferring to keep it at home to defend Australia. Labor agreed to participate in the Advisory War Council. Menzies sent the bulk of the army to help the British in the Middle East and Singapore, and told Winston Churchill the Royal Navy needed to strengthen its Far Eastern forces.[29]

From 24 January 1941 Menzies spent four months in Britain discussing war strategy with Churchill and other Empire leaders, while his position at home deteriorated. En route to the UK he took the opportunity to stop over to visit Australian troops serving in the North African Campaign. Professor David Day, an Australian historian, has posited that Menzies might have replaced Churchill as British prime minister, and that he had some support in the UK for this. Support came from Viscount Astor, Lord Beaverbrook and former WWI Prime Minister David Lloyd George,[30] who were trenchant critics of Churchill's purportedly autocratic style, and favoured replacing him with Menzies, who had some public support for staying on in the War Cabinet for the duration, which was strongly backed by Sir Maurice Hankey, former WWI Colonel and member of both the WWI and WWII War Cabinets. Writer Gerard Henderson has rejected this theory, but history professors Judith Brett and Joan Beaumont support Day, as does Menzies's daughter, Heather Henderson, who claimed Lady Astor "even offered all her sapphires if he would stay on in England".[30]

When Menzies came home, he found he had lost all support, and was forced to resign on 27 August 1941. Although the UAP had been in power for a decade, it was so bereft of leadership that it was forced to turn to the nearly 78-year-old former Prime Minister Billy Hughes as its new leader. However, Hughes was deemed too old and frail to be a wartime prime minister, and a joint UAP-Country Party conference chose Country Party leader Arthur Fadden as Coalition leader—and hence Prime Minister—even though the Country Party was nominally the junior partner in the Coalition.[31][32] Menzies was bitter about this treatment from his colleagues, and nearly left politics,[33] but was persuaded to become Minister for Defence Co-ordination in Fadden's cabinet.[34]

Formation of Liberal Party and return to power

Menzies's Forgotten People

During his time in the political wilderness Menzies built up a large popular base of support by his frequent appeals, often by radio, to ordinary non-elite working citizens whom he called 'the Forgotten People'—especially those who were not suburban and rich or members of organised labour. From November 1941, he began a series of weekly radio broadcasts reaching audiences across New South Wales, Victoria and Queensland. A selection of these talks was edited into a book bearing the title of his most famous address, The Forgotten People, delivered on 22 May 1942. In this landmark address, Menzies appealed to his support base:

I do not believe that the real life of this nation is to be found either in great luxury hotels and the petty gossip of so-called fashionable suburbs, or in the officialdom of the organised masses. It is to be found in the homes of people who are nameless and unadvertised, and who, whatever their individual religious conviction or dogma, see in their children their greatest contribution to the immortality of their race. The home is the foundation of sanity and sobriety; it is the indispensable condition of continuity; its health determines the health of society as a whole.[35]

Menzies himself described The Forgotten People collection as 'a summarized political philosophy'. Representing the blueprint of his liberal philosophy, The Forgotten People encompassed a wide range of topics including Roosevelt's Four Freedoms, the control of the war, the role of women in war and peace, the future of capitalism, the nature of democracy and especially the role of the middle class, 'the forgotten people' of the title and their importance to Australia's future as a democracy.[36] The addresses frequently emphasized the values which Menzies regarded as critical to shaping Australia's wartime and postwar polices. These were essentially the principles of liberalism: individual freedom, personal and community responsibility, the rule of law, parliamentary government, economic prosperity and progress based on private enterprise and reward for effort.[36]

Whilst Menzies was broadcasting his radio addresses, Arthur Fadden's government was defeated in Parliament in October 1941 after the two independent MPs crossed the floor, allowing Curtin to form a Labor minority government. Fadden was named as Leader of the Opposition, and Menzies moved to the backbench.[37] Labor won a crushing victory at the 1943 election, taking 49 of 74 seats and 58.2 percent of the two-party-preferred vote as well as a Senate majority. The Coalition, which had sunk into near-paralysis in opposition was knocked down to only 19 seats. Hughes, who had widely been reckoned as a stopgap leader, handed the UAP leadership back to Menzies. Fadden yielded the post of Opposition Leader back to Menzies as well.

Formation of the Liberal Party of Australia

Soon after his return in 1944, Menzies concluded that the UAP was at the end of its useful life. Menzies called a conference of parties opposed to the ruling ALP with meetings in Canberra on 13 October 1944 and again in Albury (NSW) in December 1944. At the Canberra conference, the fourteen parties decided to merge as one new non-labor party, The Liberal Party of Australia. The organisational structure and constitutional framework of the new party was formulated at the Albury Conference. Officially launched at the Sydney Town Hall on 31 August 1945, the Menzies-led Liberal Party of Australia inherited the UAP's role as senior partner in the Coalition. Curtin died in office in 1945 and was succeeded by Ben Chifley.

The reconfigured Coalition faced its first national test in the 1946 election. It won 26 of 74 seats on 45.9 percent of the two-party vote, and remained in minority in the Senate. Despite winning a seven-seat swing, the Coalition failed to make a serious dent in Labor's large majority.

1949 Election Campaign

Over the next few years, however, the anti-communist atmosphere of the early Cold War began to erode Labor's support. In 1947, Chifley announced that he intended to nationalise Australia's private banks, arousing intense middle-class opposition which Menzies successfully exploited. In addition to campaigning against Chifley's bank nationalization proposal, Menzies successfully led the 'No' case for a referendum by the Chifley government in 1948 to extend commonwealth wartime powers to control rents and prices.[38] In the election campaign of 1949, Menzies and his party were resolved to stamp out the communist movement and to fight in the interests of free enterprise against what they termed as Labor's 'socialistic measures'. If Menzies won office, he pledged to counter inflation, extend child endowment and end petrol rationing.[39] With the lower house enlarged from 74 to 121 seats, the Menzies Liberal/Country Coalition won the 1949 election with 74 House seats and 51.0 percent of the two-party vote but remained in minority in the Senate. Whatever else Menzies's victory represented, his anti-communism and advocacy for free enterprise had captured a new and formidable support base in postwar Australian society.[40]

Second term as prime minister, 1949–1966

After his election victory, Menzies returned to the office of Prime Minister on 19 December 1949. Menzies's second prime ministership lasted a record sixteen years, and was to end in his voluntary retirement on 26 January 1966 at the age of 71. Over this time he won seven general elections. Menzies second term in office was marked by extraordinary economic growth. The 'long boom' was experienced in most advanced economies, but the Menzies's government's stability, their declared policies of 'development' and their continuance of the ambition immigration programme initiated by Labor were factors in a transformation of Australian material life, as indicated by markers as various a growth in population and home ownership, the ubiquity of whitegoods, and a great jump in motor-vehicle ownership.[41]

Cold War and national security

The spectre of communism and the threat it deemed to pose to national security became the dominant preoccupation of the new government in its first phase. Menzies introduced legislation in 1951 to ban the Communist Party, hoping that the Senate would reject it and give him a trigger for a double dissolution election, but Labor let the bill pass. It was subsequently ruled unconstitutional by the High Court. But when the Senate rejected his banking bill, he called a double dissolution election. At that election, the Coalition suffered a five-seat swing, winning 69 of 121 seats and 50.7 percent of the two-party vote. However, it won six seats in the Senate, giving it control of both chambers. Later in 1951 Menzies decided to hold a referendum on the question of changing the Constitution to permit the parliament to make laws in respect of Communists and Communism where he said this was necessary for the security of the Commonwealth. If passed, this would have given a government the power to introduce a bill proposing to ban the Communist Party. Chifley died a few months after the 1951 election. The new Labor leader, Dr H. V. Evatt, campaigned against the referendum on civil liberties grounds, and it was narrowly defeated. Menzies sent Australian troops to the Korean War.

Economic conditions deteriorated in the early 1950s and Labor was confident of winning the 1954 election. Shortly before the election, Menzies announced that a Soviet diplomat in Australia Vladimir Petrov, had defected, and that there was evidence of a Soviet spy ring in Australia, including members of Evatt's staff. Evatt felt compelled to state on the floor of Parliament that he'd personally written to Soviet Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov, who assured him there were no Soviet spy rings in Australia, bringing the House into silence momentarily before both sides of Parliament laughed at Evatt's naivety.[42]

This Cold War scare was claimed by some to enable the Menzies government to win the election. The Menzies government won 64 of 121 seats and 49.3 percent of the two-party vote. Evatt accused Menzies of arranging Petrov's defection. The aftermath of the 1954 election caused a split in the Labor Party, with several anti-Communist members from Victoria defecting to form the Australian Labor Party. The new party directed its preferences to the Liberals, with the Menzies government re-elected with an increased majority at the 1955 election. Menzies was re-elected almost as easily at the 1958 election, again with the help of preferences from what had become the Democratic Labor Party. By this time the post-war economic recovery was in full swing, fuelled by massive immigration and the growth in housing and manufacturing that this produced. Prices for Australia's agricultural exports were also high, ensuring rising incomes.

Foreign policy

The Menzies era saw immense regional changes, with post-war reconstruction and the withdrawal of European Powers and the British Empire from the Far East (including independence for India and Indonesia). In response to these geopolitical developments, the Menzies government maintained strong ties with Australia's traditional allies such as Britain and the United States while also reorienting Australia's foreign policy focus towards the Asia Pacific. With his first Minister for External Affairs, Percy Spender, the Menzies government signed the ANZUS treaty in San Francisco on 1 September 1951. Menzies later told parliament that this security pact between Australia, New Zealand and the United States was 'based on the utmost good will, the utmost good faith and unqualified friendship' saying 'each of us will stand by it'.[43] At the same time as strengthening the alliance with the United States, Menzies and Spender were committed to Australia been on 'good neighbour terms' with the countries of South and South East Asia. To help forge closer ties in the region, the Menzies government initiated the Colombo Plan that would see almost 40 000 students from the region come to study in Australia over the four subsequent decades.[44] Recognising the economic potential of a burgeoning postwar Japan, Menzies, together with Trade Minister Jack McEwan and his new minister for External Affairs, Richard Casey, negotiated the Commerce Agreement with Japan in 1957. This trade agreement was followed by bilateral agreements with Malaya in 1958 and Indonesia in 1959.[45] With the Menzies government expanding Australia's diplomatic footprint in the region during its second term, a further six new high commissions and embassies were established in South East Asia from 1949 to 1966. Complementing Australia's growing diplomatic engagement in Asia, the Menzies government delivered a comprehensive aid programme to the region which comprised 0.65 per cent of Australia's Gross National Income by 1966.

While engaging Australia more closely with its neighbours in the Asia Pacific, the Menzies government maintained a strong interest in British and European affairs, especially the unfolding Suez Crisis of 1956. With the Egyptian leader Colonel Nasser's nationalization of the Suez Canal Company on 26 July 1956, Britain and France reacted angrily to Egypt's restriction on the free use of this waterway for international trade and commerce. Sympathetic to British interests, Menzies led a delegation to Egypt to try to force Nasser to compromise with the West. Although, at the time it was seen as confirming Menzies's status as a world statesman, it was of vital importance to Australia's shipping trade with Britain. Menzies publicly supported the Anglo-French invasion of Egypt during the Suez Crisis.

Elsewhere, Menzies publicly professed continued admiration for links with Britain, exemplified by his admiration for Queen Elizabeth II, and famously described himself as "British to the bootstraps". Over the decade, Australia's ardour for Britain and the monarchy faded somewhat, but Menzies's had not. At a function attended by the Queen at Parliament House, Canberra, in 1963, Menzies quoted the Elizabethan poet Thomas Ford, "I did but see her passing by, and yet I love her till I die".

Defence policy

Confronting the challenges of the Cold War, the Menzies government shifted Australia to a policy of 'forward defence' as the most effective means of dealing with the threat of communism abroad. Australia's defence policy was conducted in close cooperation with the United States under the aegis of the ANZUS treaty. The Menzies government responded to successive communist insurgencies by committing Australian troops to the Korean War of 1950–51, the Malayan Emergency from 1948 to 1960, the Borneo Confrontation of 1963 and to the escalating conflict in Vietnam in 1965. To strengthen defense ties with countries in the Asia Pacific region, the Menzies government signed the South East Asia Collective Defence Treaty (SEATO) as a South East Asian counterpart to NATO. On the domestic front, the Menzies government introduced a scheme of national service where 'call ups' were issued to 18-year-old men to undertake a period of compulsory military training. Established in 1951, the scheme ended in 1960 but was reintroduced in 1964 in the form of the National Service Lottery.

Economic policy

Throughout his second term in office, Menzies practised classical liberal economics with an emphasis on private enterprise and self-sufficiency in contrast to Labor's 'socialist objective'. Accordingly, the economic policy emphasis of the Menzies Government moved towards tax incentives to release productive capacity, boosting export markets, research and undertaking public works to provide power, water and communications.[46] As Prime Minister, Menzies presided over a period of sustained economic growth which led to nation-building and development, full employment, unprecedented opportunities for individuals and rising living standards.

Social reform

In 1949, Parliament legislated to ensure that all Aboriginal ex-servicemen should have the right to vote. In 1961 a Parliamentary Committee was established to investigate and report to the Parliament on Aboriginal voting rights and in 1962, Menzies's Commonwealth Electoral Act provided that all Indigenous Australians should have the right to enrol and vote at federal elections.[47]

In 1960, the Menzies Government introduced a new pharmaceutical benefits scheme, which expanded the range of prescribed medicines subsidised by the government. Other social welfare measures of the Menzies government included the extension of the Commonwealth Child Endowment scheme, the pensioner medical and free medicines service, the Aged Persons' Homes Assistance scheme, free provision of life-saving drugs; the provision of supplementary pensions to dependent pensioners paying rent; increased rates of pension, unemployment and sickness benefits, and rehabilitation allowances; and a substantial system of tax incentives and rewards.[48] In 1961, The Matrimonial Causes Act introduced a uniform divorce law across Australia, provided funding for marriage counselling services and made allowances for a specified period of separation as sufficient grounds for a divorce.[49]

In response to the decision by the Catholic Diocese of Goulburn in July 1962 to close its schools in protest at the lack of government assistance, the Menzies government announced a new package of state aid for independent and Catholic schools. Menzies promised five million pounds annually for the provision of buildings and equipment facilities for science teaching in secondary schools. Also promised were 10 000 scholarships to helps students stay at school for the last two years with a further 2 500 scholarships for technical schools.[50] Despite the historically firm Catholic support base of the Labor Party, the Opposition under Calwell opposed state aid before eventually supporting it with the ascension of Gough Whitlam as Labor leader.

In 1965, the Menzies Government took the decision to end open discrimination against married women in the public service, by allowing them to become permanent public servants, and allowing female officers who were already permanent public servants to retain that status after marriage.[51]

Immigration policy

The Menzies government maintained and indeed expanded the Chifley Labor government's postwar immigration scheme established by Immigration Minister, Arthur Calwell in 1947. Beginning in 1949, Immigration Minister Harold Holt decided to allow 800 non-European war refugees to remain in Australia, and Japanese war brides to be admitted to Australia.[52] In 1950 External Affairs Minister Percy Spender instigated the Colombo Plan, under which students from Asian countries were admitted to study at Australian universities, then in 1957 non-Europeans with 15 years' residence in Australia were allowed to become citizens. In a watershed legal reform, a 1958 revision of the Migration Act introduced a simpler system for entry and abolished the "dictation test" which had permitted the exclusion of migrants on the basis of their ability to take down a dictation offered in any European language. Immigration Minister, Sir Alexander Downer, announced that 'distinguished and highly qualified Asians' might immigrate. Restrictions continued to be relaxed through the 1960s in the lead up to the Holt Government's watershed Migration Act, 1966.[53]

Higher education expansion

The Menzies government extended Federal involvement in higher education and introduced the Commonwealth scholarship scheme in 1951, to cover fees and pay a generous means-tested allowance for promising students from lower socioeconomic groups.[54] In 1956, a committee headed by Sir Keith Murray was established to inquire into the financial plight of Australia's universities, and Menzies's pumped funds into the sector under conditions which preserved the autonomy of universities.[55] In its support for higher education, the Menzies government tripled Federal government funding and provided emergency grants, significant increases in academic salaries, extra funding for buildings, and the establishment of a permanent committee, from 1961, to oversee and make recommendations concerning higher education.[56]

Development of Canberra as a national capital

The Menzies government developed the city of Canberra as the national capital. In 1957, the Menzies government established the National Capital Development Commission as independent statutory authority charged with overseeing the planning and development of Canberra.[57] During Menzies time in office, the great bulk of the federal public service moved from the state capitals to Canberra.[57]

After politics

Menzies resigned as prime minister on Australia Day 1966, and resigned from Parliament on 16 February, ending 32 years in Parliament (most of them spent as either a cabinet minister or opposition frontbencher), a combined 25 years as leader of the non-Labor Coalition, and 38 years as an elected official. To date, Menzies is the last Australian prime minister to leave office on their own terms. He was succeeded as Liberal Party leader and prime minister by his former treasurer, Harold Holt. He left office at the age of 71 years, 1 month and 6 days, making him the oldest person ever to be prime minister. Although the coalition remained in power for almost another seven years (until the 1972 Federal election), it did so under four different prime ministers, largely due to his successor's death, only 22 months after taking office.

On his retirement he became the thirteenth chancellor of the University of Melbourne and remained the head of the university from March 1967 until March 1972. Much earlier, in 1942, he had received the first honorary degree of Doctor of Laws of Melbourne University. His responsibility for the revival and growth of university life in Australia was widely acknowledged by the award of honorary degrees in the Universities of Queensland, Adelaide, Tasmania, New South Wales, and the Australian National University and by thirteen universities in Canada, the United States and Britain, including Oxford and Cambridge. Many learned institutions, including the Royal College of Surgeons (Hon. FRCS) and the Royal Australasian College of Physicians (Hon. FRACP), elected him to Honorary Fellowships, and the Australian Academy of Science, for which he supported its establishment in 1954, made him a fellow (FAAS) in 1958. On 7 October 1965, Menzies was installed as the ceremonial office of Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports and Constable of Dover Castle as appointed by the Queen, which included an official residence at Walmer Castle during his annual visits to Britain. At the end of 1966 Menzies took up a scholar-in-residence position at the University of Virginia. He presented a series of lectures, published the following year as Central Power in the Australian Commonwealth. He later published two volumes of memoirs. In March 1967 he was elected Chancellor of Melbourne University, serving a five-year term.[58][59] In 1971, Menzies suffered a severe stroke and was permanently paralyzed on one side of his body for the remainder of his life. He suffered a second stroke in 1972. His official biographer, Lady McNicoll wrote after his death in The Australian that Menzies was "splendid and sharp right up until the end" also that "each morning he underwent physiotherapy and being helped to face the day." In March 1977, Menzies accepted his Order of Australia (AK) from Queen Elizabeth in a wheelchair in the Long Room of the Melbourne Cricket Ground during the Centenary Test.[60]

Death and funeral

Menzies died from a heart attack[61] while reading in his study at his Haverbrack Avenue home in Malvern, Melbourne on 15 May 1978. Tributes from across the world were sent to the Menzies family. Notably among those were from HM Queen Elizabeth II, Queen of Australia: "I was distressed to hear of the death of Sir Robert Menzies. He was a distinguished Australian whose contribution to his country and the Commonwealth will long be remembered." and from Malcolm Fraser, Prime Minister of Australia: "All Australians will mourn his passing. Sir Robert leaves an enduring mark on Australian history." Menzies was accorded a state funeral, held in Scots' Church, Melbourne on 19 May at which Prince Charles represented the Queen.[62] Other dignitaries to attend included current and former Prime Ministers of Australia Malcolm Fraser, John McEwen, John Gorton and William McMahon as well as the Governor General of Australia, Sir Zelman Cowan. Former Prime Ministers of the United Kingdom Alec Douglas-Home and Harold Wilson also attended.

The service was and is to this day one of the largest state funerals ever held in Australia, with over 100,000[63] people lining the streets of Melbourne from Scots' Church to Springvale Crematorium, where a private service was held for the Menzies family and a 19-gun salute was fired at the end of the ceremony. In July 1978, a memorial service was held for Menzies in the United Kingdom at Westminster Abbey.[64] A memorial dedicated to Sir Robert and Dame Pattie Menzies is placed in the 'Prime Ministers Garden' within the grounds of Melbourne General Cemetery.

Some of Menzies detractors also commemorated his passing in 1978, with a screen printed Poster, Pig Iron Bob / Dead at last, designed by Chips Mackinolty from the Earthworks Poster Collective.[65]

Religious views

Menzies was the son of a Presbyterian-turned-Methodist lay preacher and imbibed his father's Protestant faith and values. During his studies at the University of Melbourne, Menzies served as president of the Students' Christian Union.[66] Proud of his Scottish Presbyterian heritage with a living faith steeped in the Bible, Menzies nonetheless preached religious freedom and non-sectarianism as the norm for Australia. Indeed, his cooperation with Australian Catholics on the contentious state aid issue was recognised when he was invited as guest of honour to the annual Cardinal's Dinner in Sydney 1964, presided over by Cardinal Norman Gilroy.[67]

Legacy

Menzies was by far the longest-serving Prime Minister of Australia, in office for a combined total of 18 years, five months and 12 days. His second term of 16 years, one month and seven days is far and away the longest unbroken tenure in that office. During his second term he dominated Australian politics as no one else has ever done. He managed to live down the failures of his first term in office and to rebuild the conservative side of politics from the nadir it hit at the 1943 election. However, it can also be noted that while retaining government on each occasion, Menzies lost the two-party-preferred vote at three separate elections – in 1940, 1954 and 1961.[68][69]

He was the only Australian prime minister to recommend the appointment of four governors-general (Viscount Slim, and Lords Dunrossil, De L'Isle, and Casey). Only two other prime ministers have ever chosen more than one governor-general.[70]

The Menzies era saw Australia become an increasingly affluent society, with average weekly earnings in 1965 50% higher in real terms than in 1945. The increased prosperity enjoyed by most Australians during this period was accompanied by a general increase in leisure time, with the five-day workweek becoming the norm by the mid-Sixties, together with three weeks of paid annual leave.[71]

Several books have been filled with anecdotes about Menzies. While he was speaking in Williamstown, Victoria, in 1954, a heckler shouted, "I wouldn't vote for you if you were the Archangel Gabriel" – to which Menzies coolly replied "If I were the Archangel Gabriel, I'm afraid you wouldn't be in my constituency."[72]

Planning for an official biography of Menzies began soon after his death, but it was long delayed by Dame Pattie Menzies' protection of her husband's reputation and her refusal to co-operate with the appointed biographer. In 1991, the Menzies family appointed Professor A.W. Martin to write a biography, which appeared in two volumes, in 1993 and 1999. The National Museum of Australia in Canberra holds a significant collection of memorabilia relating to Robert Menzies, including a range of medals and civil awards received by Sir Robert such as his Jubilee and Coronation medals, Order of Australia, Companion of Honour and US Legion of Merit. There are also a number of special presentation items including a walking stick, cigar boxes, silver gravy boats from the Kooyong electorate and a silver inkstand presented by Queen Elizabeth II.[73] Robert Menzies's personal library of almost 4,000 books is held at the University of Melbourne Library.[74]

Published works

- The Forgotten People: and other studies in democracy (Sydney: Angus and Robertson, 1942)

- Speech is of Time: selected speeches and writings (London: Cassell, 1958)

- Afternoon Light: some memories of men and events (Melbourne: Cassell Australia, 1967)

- Central Power in the Australian Commonwealth: an examination of the growth of Commonwealth power in the Australian Federation (London: Cassell, 1967)

- The Measure of the Years (Melbourne: Cassell Australia, 1970)

- Dark and Hurrying Days: Menzies' 1941 diary (Canberra: National Library of Australia, 1993)

- Letters to my Daughter (Miller's Point: Murdoch Books, 2011)

Titles and honours

- In 1950 Menzies was awarded the Legion of Merit (Chief Commander) by US President Harry S. Truman for "exceptionally meritorious conduct in the performance of outstanding services 1941–1944 and December 1949 – July 1950".

- On 1 January 1951 he was appointed to the Order of the Companions of Honour (CH)[75]

- On 29 August 1952, the University of Sydney conferred the degree of Doctor of Laws (honoris causa) on Menzies.[76] Similarly, He was awarded an Honorary Doctor of Laws by the Universities of Bristol, Belfast, Melbourne, British Columbia, McGill, Montreal, Malta, Laval, Quebec, Tasmania, Cambridge, Harvard, Leeds, Adelaide, Queensland, Edinburgh, Birmingham, Drury and California.[77]

- In 1963, Menzies was appointed a Knight of the Order of the Thistle (KT),[78] the order being chosen in recognition of his Scottish heritage. He is the only Australian ever appointed to this order. He was the second of only two Australian prime ministers to be knighted during their term of office (the first prime minister, Edmund Barton, was knighted during his term in 1902).

- On 29 April 1964 Menzies was awarded the honorary degree of a Doctor of Letters (DLitt) by the University of Western Australia.[79] Menzies was also awarded with an Honorary Doctor of Science by the University of New South Wales.[77]

- In 1973 Menzies was awarded Japan's Order of the Rising Sun, Grand Cordon, First Class (other Australian prime ministers to be awarded this honour were Edmund Barton, John McEwen, Malcolm Fraser and Gough Whitlam).[80]

- On 7 June 1976, he was appointed a Knight of the Order of Australia (AK). The category of Knight of the order had been created only on 24 May, and the Chancellor and Principal Knight of the Order, the Governor-General Sir John Kerr, became the first appointee, ex officio. Menzies's was the first appointment made after this.

- In 1984, the Australian Electoral Commission proclaimed at a redistribution on 14 September 1984, the Division of Menzies for representation in the Australian House of Representatives in honour of the former prime minister. The division neighbours Menzies's old division of Kooyong in metropolitan Melbourne, Victoria.

- In 1994, the year of the centenary of Menzies' birth, the Menzies Research Centre was created as an independent public policy think tank associated with the Liberal Party.

- In 2009, during the Australia Day celebrations, the R.G. Menzies Walk was officially opened by the then Governor General of Australia, Dame Quentin Bryce. The walk runs alongside the northern shore of Lake Burley Griffin in Australia's capital, Canberra.[81]

- In 2012, a life-sized bronze statue of Menzies was erected on the R.G. Menzies Walk.[82]

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Decorations

-

1950, he was appointed a Chief Commander of the Legion of Merit

1950, he was appointed a Chief Commander of the Legion of Merit

-

1951, he was appointed a Companion of the Order of the Companions of Honour (CH)

1951, he was appointed a Companion of the Order of the Companions of Honour (CH)

-

1963, he was appointed a Knight of the Order of the Thistle (KT)

1963, he was appointed a Knight of the Order of the Thistle (KT)

-

1973, he was appointed a Grand Cordon First Class of the Order of the Rising Sun

1973, he was appointed a Grand Cordon First Class of the Order of the Rising Sun

-

1976, he was appointed a Knight of the Order of Australia (AK)

1976, he was appointed a Knight of the Order of Australia (AK)

Medals

-

1935, he was awarded the King George V Silver Jubilee Medal

1935, he was awarded the King George V Silver Jubilee Medal

-

1937, he was awarded the King George VI Coronation Medal

1937, he was awarded the King George VI Coronation Medal

-

1953, he was awarded the Queen Elizabeth II Coronation Medal

1953, he was awarded the Queen Elizabeth II Coronation Medal

Freedom of the City

- British Empire

-

18 November 1948: Edinburgh

18 November 1948: Edinburgh -

6 June 1953: Oxford

6 June 1953: Oxford -

1966: Melbourne [83]

1966: Melbourne [83]

Styles from birth

Styles and titles Menzies held from birth until death, in chronological order:

- Mr Robert Menzies (20 December 1894 – 1928)

- The Hon. Robert Menzies, MLC (1928–1929)

- The Hon. Robert Menzies, MLA (1929–1929)

- The Hon. Robert Menzies, KC, MLA (1929–1934)

- The Hon. Robert Menzies, KC, MP (1934–1937)

- The Rt Hon. Robert Menzies, KC, MP (1937–1951)

- The Rt Hon. Robert Menzies, CH, KC, MP (1951–1952)

- The Rt Hon. Robert Menzies, CH, QC, MP (1952–1958)

- The Rt Hon. Robert Menzies, CH, FAA, QC, MP (1958–1963)

- The Rt Hon. Sir Robert Menzies, KT, CH, FAA, QC, MP (1963–1965)

- The Rt Hon. Sir Robert Menzies, KT, CH, FAA, FRS, QC, MP (1965–1966)

- The Rt Hon. Sir Robert Menzies, KT, CH, FAA, FRS, QC (1966–1976)

- The Rt Hon. Sir Robert Menzies, KT, AK, CH, FAA, FRS, QC (1976 – 15 May 1978)

See also

- First Menzies Ministry

- Second Menzies Ministry

- Third Menzies Ministry

- Fourth Menzies Ministry

- Fifth Menzies Ministry

- Sixth Menzies Ministry

- Seventh Menzies Ministry

- Eighth Menzies Ministry

- Ninth Menzies Ministry

- Tenth Menzies Ministry

Actors who have played Menzies

- In the 1984 mini series The Last Bastion, Menzies was portrayed by John Wood.

- In the 1987 mini series Vietnam, he was portrayed by Noel Ferrier.

- In the 1988 mini series True Believers, he was portrayed by John Bonney.

- In the 1996 Egyptian film Nasser 56, he was portrayed by Egyptian actor Hassan Kami.

- In the 2007 film Curtin, he was portrayed by Bille Brown.

- In the 2008 television documentary Menzies and Churchill at War, he was portrayed by Matthew King.

- Max Gillies has caricatured Menzies on stage and in the comedy satire series The Gillies Report.

- In the 2015 documentary The Dalfram Dispute 1938 (Pig Iron Bob) www.pigironbob.com.authedalframdispute1938.com.au Menzies was portrayed by Bob Baines

Eponyms of Menzies

- Sir Robert Menzies Memorial Foundation

- Menzies School of Health Research Australia

- R. G. Menzies Building, Australian National University Library

- Menzies Research Centre

- Menzies College (La Trobe University)

- Robert Menzies College (Macquarie University)

- Sir Robert Menzies Building (Monash University, Clayton Campus)

- The Australian federal electoral division of Menzies.[84]

- Menzies Wing (Wesley College, Melbourne)

- Menzies Research Institute

Further reading

- Brett, Judith (1992) Robert Menzies' Forgotten People, Macmillan, (a sharply critical psychological study)

- Cook, Ian (1999), Liberalism in Australia, Oxford University Press, South Melbourne, Victoria, Ch. 7 'Robert Menzies'. ISBN 0-19-553702-5

- Day, David. (1993) Menzies and Churchill at War (Oxford University Press)

- Hazlehurst, Cameron (1979), Menzies Observed, George Allen and Unwin, Sydney, New South Wales. ISBN 0-86861-320-7

- Henderson, Anne. (2014) Menzies at War

- Hughes, Colin A (1976), Mr Prime Minister. Australian Prime Ministers 1901–1972, (Melbourne: Oxford University Press) Chs. 13 and 18. ISBN 0-19-550471-2

- Martin, A.W. (1993 and 1999) Robert Menzies: A Life, two volumes, Melbourne University Press online edition from ACLS E-Books

- Martin, Allan (2000), 'Sir Robert Gordon Menzies,' in Grattan, Michelle, "Australian Prime Ministers", New Holland Publishers, pages 174–205. (very good summary of his life and career) ISBN 1-86436-756-3

- Martin, A.W. (2000), "Menzies, Sir Robert Gordon (Bob) (1894 – 1978)", Australian Dictionary of Biography, Volume 15, Melbourne University Press, (Melbourne), pp 354–361.[38]

- Nethercote, J.R.(ed). (2016) Menzies: The Shaping of Modern Australia, Connor Court.

- Starr, Graeme (1980), The Liberal Party of Australia. A Documentary History, Drummond/Heinemann, Richmond, Victoria. ISBN 0-85859-223-1

Notes and references

- ↑ Warhurst, John. "The religious beliefs of Australia's prime ministers". eurekastreet.com.au. Retrieved 1 May 2014.

- ↑ White, F. (1979). "Robert Gordon Menzies. 20 December 1894 – 15 May 1978". Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society. 25: 445–426. doi:10.1098/rsbm.1979.0016.

- 1 2 3 4 Australia's Prime Ministers website: Robert Menzies

- 1 2 "Parliament of Victoria – Re-Member".

- ↑ Australian Academy of Science: Biographical Memoirs of Deceased Fellows: Robert Gordon Menzies 1894–1978

- ↑ Manning Clark, Manning Clark's History of Australia, Pimlico, 1995, p.468, ISBN 0-7126-6205-7. Gordon's death had stirred a lasting movement of imperialist patriotism in Australia.

- ↑ "Before office – Robert Menzies – Australia's PMs – Australia's Prime Ministers".

- ↑ "NAA: B2455, MENZIES FRANK GLADSTONE".

- ↑ http://recordsearch.naa.gov.au/scripts/Imagine.asp?B=8030675

- ↑ "Australia's Prime Ministers". Primeministers.naa.gov.au. Retrieved 4 November 2011.

- 1 2 Martin, Allan W. (1993). Robert Menzies: A Life Volume 1 1894–1943. Melbourne: Melbourne University Press. p. 285. ISBN 0-522-84442-1.

- 1 2 Martin, Allan W (2000). "Menzies, Sir Robert". Australian Dictionary of Biography.

- 1 2 http://www.menziescollection.esrc.unimelb.edu.au/biogs/E000548b.htm

- ↑ http://www.menziescollection.esrc.unimelb.edu.au/biogs/E002155b.htm

- ↑ https://www.myheritage.com/research/collection-10450/argus-melbourne-vic-sep-19-1949?itemId=28985182&action=showRecord

- ↑ http://www.menziescollection.esrc.unimelb.edu.au/biogs/E000119b.htm

- ↑ http://www.smh.com.au/entertainment/books/daughters-insights-cast-new-light-on-robert-menzies-20140307-34aow.html

- ↑ Martin. Robert Menzies. pp. 66–67.

- ↑ "Australia's PMs, Robert Menzies, Before Office".

- ↑ Peter Monteath, "The Kisch visit revisited." Journal of Australian Studies 16#34 (1992) pp: 69–81.

- ↑ "Australian Dictionary of Biography, Menzies, Sir Robert Gordon (Bob) (1894–1978)".

- ↑ David Bird (15 February 2014). Nazi Dreamtime: Australian Enthusiasts for Hitler’s Germany. Anthem Press. pp. 405–. ISBN 978-1-78308-124-0.

- ↑ Christopher Waters, "Understanding and Misunderstanding Nazi Germany: Four Australian visitors to Germany in 1938," Australian Historical Studies (2010) 41#3 pp: 369–384

- ↑ E. M. Andrews, "The Australian Government and Appeasement." Australian Journal of Politics & History 13.1 (1967): 34-46.

- ↑ Robert Menzies, Declaration of War, broadcast 3 September 1939

- ↑ Menzies, Robert (1939). Declaration of War.

- ↑ Mallory, Greg (1999). "The 1938 Dalfram Pig-iron Dispute and Wharfies Leader, Ted Roach". The Hummer. Australian Society for the Study of Labour History. 3 (2).

- ↑ David Day, Menzies and Churchill at War (1993) pp 9–26

- ↑ Paul Hasluck, The Government and the People: 1939–1941 (1951)

- 1 2 Australian Broadcasting Corporation documentary "Menzies and Churchill at War" (2008) by Film Australia.

- ↑ "After office – William Morris Hughes – Australia's PMs". Primeministers.naa.gov.au. Retrieved 17 October 2012.

- ↑ "Before office – Arthur Fadden – Australia's PMs – Australia's Prime Ministers". Primeministers.naa.gov.au. Retrieved 17 October 2012.

- ↑ Scott Brodie (1984). Australia's Prime Ministers. NSW, Australia: PR Books. ISBN 0 86777 006 6.

- ↑ "Ministries and Cabinets". parliamentary Handbook. Parliament of Australia. Retrieved 17 September 2010.

- ↑ "The Forgotten People – Speech by Robert Menzies (22 May 1942)". Liberals.net. 22 May 1942. Retrieved 4 November 2011.

- 1 2 Menzies, Robert; Kemp, David (2011). The Forgotten People and Other Studies in Democracy. Melbourne: The Liberal Party of Australia (Victorian Division). p. 12. ISBN 9780646555171.

- ↑ "In office – Robert Menzies – Australia's PMs". Primeministers.naa.gov.au. Retrieved 17 October 2012.

- 1 2 "Menzies, Sir Robert Gordon (Bob) (1894–1978) Biographical Entry – Australian Dictionary of Biography Online". Adb.online.anu.edu.au. Retrieved 16 April 2010.

- ↑ "Menzies, Sir Robert Gordon (Bob) (1894–1978)".

- ↑ "Menzies, Sir Robert Gordon (Bob) (1894–1978)".

- ↑ "Menzies, Sir Robert (Gordon) 1894–1978".

- ↑ "Royal Commission – The Petrov Affair".

- ↑ "Josh Frydenberg, 2014 Sir Robert Menzies Lecture".

- ↑ "Josh Frydenberg 2014 Sir Robert Menzies Lecture".

- ↑ "Josh Frydenberg, 2014 Sir Robert Menzies Lecture".

- ↑ Starr, Graeme (2001). "Menzies and Post-War Prosperity". Liberalism and the Australian Federation edited by John Nethercote.

- ↑ "Indigenous Vote".

- ↑ Nethercote, John (2001). Liberalism and the Australian Federation. Sydney: Federation Press. p. 191. ISBN 1862874026.

- ↑ "Australia's Prime Ministers, Robert Menzies, Timeline".

- ↑ Howard, John (2014). The Menzies Era: The Years that Shaped Modern Australia. Sydney: HarperCollins Publishers. pp. 320–321. ISBN 9780732296124.

- ↑ Howard. Menzies Era. p. 351.

- ↑ "Fact Sheet – Abolition of the "White Australia" Policy".

- ↑ "Fact Sheet – Abolition of the "White Australia" Policy".

- ↑ Henderson, Gerard (26 April 2011). "The way we were: quiet, maybe, but certainly not dull". Sydney Morning Herald.

- ↑ "Menzies, Sir Robert Gordon (Bob) (1894–1978)".

- ↑ Howard. The Menzies Era. p. 246.

- 1 2 Howard. Menzies Era. p. 350.

- ↑ "MENZIES Robert Gordon". Legal Opinions. Australian Government Solicitor. Retrieved 7 May 2014.

- ↑ "Former Office-Bearers". University Secretary's Department University Calendar. The University of Melbourne. Retrieved 7 May 2014.

- ↑ http://menziesvirtualmuseum.org.au/the-1970s/menzies-reflects-australia-matures| Menzies Research Center – Retrieved 2016-02-07

- ↑ https://www.menziesrc.org/sir-robert-menzies/history-of-sir-robert-menzies | Menzies Research Centre – Retrieved 2016-02-06

- ↑ "Prince here tomorrow – Rush trip to Menzies funeral". The Age. Melbourne. 17 May 1978. p. 1. Retrieved 12 August 2010.

- ↑ http://newsweekly.com.au/article.php?id=155| Newsweekly 2000 – Retrieved 2016-02-06

- ↑ http://primeministers.naa.gov.au/primeministers/menzies/after-office.aspx | NAA – Former Prime Ministers, Menzies after office – Retrieved 2016-02-06

- ↑ Powerhouse Museum. "Poster, 'Pig Iron Bob dead at last'". Powerhouse Museum, Australia. Retrieved 22 September 2016. The poster is part of the Di Holloway collection at the Sydney Powerhouse Museum

- ↑ Martin. Robert Menzies. pp. 22 and 23.

- ↑ Howard. Menzies Era. p. 325.

- ↑ Julia 2010: The caretaker election (1940 2PP)

- ↑ House of Representatives - Two party preferred results 1949 - present: AEC

- ↑ Governor-General of Australia

- ↑ Stuart Macintyre. A Concise History of Australia.

- ↑ In Office - Robert Menzies: NAA

- ↑ "Inkstand presented to Sir Robert Menzies in Commemoration of the Commonwealth Royal Tour 1954, National Museum of Australia". Nma.gov.au. Retrieved 4 November 2011.

- ↑ The Robert Menzies Collection: A Living Library; retrieved 18 October 2013.

- ↑ "Its an Honour: CH". Australian Government. Retrieved 15 October 2009.

- ↑ "The Right Honourable Robert Gordon Menzies". University of Sydney. Archived from the original on 18 August 2010. Retrieved 15 October 2009.

- 1 2 "University Secretary's Department – Former Office-Bearers". University of Melbourne. Retrieved 15 October 2009.

- ↑ The London Gazette: no. 42964. p. 3155. 9 April 1963. Retrieved 30 October 2008.

- ↑ "Speech by Sir Robert Menzies in Winthrop Hall, University of Western Australia". University of Western Australia. Retrieved 15 October 2009.

- ↑ Honour awarded 1973 – National Archives of Australia Archived 20 May 2009 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "R. G. Menzies Walk 'National Capital'". Retrieved 2016-03-08.

- ↑ http://www.canberratimes.com.au/act-news/permanent-place-for-menzies-in-nations-heart-20120323-1vpob.html | Permanent Place for Menzies in nations heart, Canberra Times – Retrieved 20160308

- ↑ "Freedom of city for Sir Robert". The Age. 9 April 1966. p. 3.

- ↑ Origins of Current Divisions Name – Current Divisions, Australian Electoral Commission web site

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Robert Menzies. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Robert Menzies |

- Papers of Robert Menzies, 1905–1978, National Library of Australia, approximately 82.30 m. (588 boxes) + 99 fol. boxes.

- "Robert Menzies". Australia's Prime Ministers. National Archives of Australia. Retrieved 29 June 2010.

- Martin, A. W. (2000). "Menzies, Sir Robert Gordon (Bob) (1894–1978)". Australian Dictionary of Biography. Canberra: Australian National University. Retrieved 29 June 2010.

- "Robert Menzies". National Museum of Australia. Retrieved 29 June 2010.

- The Menzies Foundation

- The Menzies Virtual Museum

- The Menzies Centre for Australian Studies, London

- The Liberal Party's Robert Menzies website

- Listen to Menzies's declaration of war on australianscreen online

- Menzies's declaration of war was added to the National Film and Sound Archive's Sounds of Australia registry in 2010

- Sir Robert Menzies at the National Film and Sound Archive

- The Robert Menzies Collection: A Living Library

- Robert Menzies Notebook Collection, The University of Melbourne

| Library resources about Robert Menzies |

- Charcoal Sketch – Menzies Collection