Rufous-crowned sparrow

| Rufous-crowned sparrow | |

|---|---|

| |

| Aimophila ruficeps eremoeca, in Texas | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Family: | Emberizidae |

| Genus: | Aimophila |

| Species: | A. ruficeps |

| Binomial name | |

| Aimophila ruficeps (Cassin, 1852) | |

| Subspecies | |

|

See text | |

| |

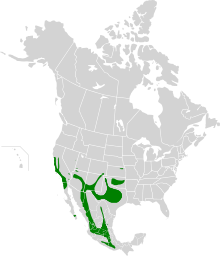

| Range of A. ruficeps resident populations | |

| Synonyms | |

The rufous-crowned sparrow (Aimophila ruficeps) is a small American sparrow. This passerine is primarily found across the Southwestern United States and much of the interior of Mexico, south to the transverse mountain range, and to the Pacific coast to the southwest of the transverse range. Its distribution is patchy, with populations often being isolated from each other. Twelve subspecies are generally recognized, though up to eighteen have been suggested. This bird has a brown back with darker streaks and gray underparts. The crown is rufous, and the face and supercilium are gray with a brown or rufous streak extending from each eye and a thick black malar streak.

These sparrows feed primarily on seeds in the winter and insects in the spring and summer. The birds are often territorial, with males guarding their territory through song and displays. Flight is awkward for this species, which prefers to hop along the ground for locomotion. They are monogamous and breed during spring. Two to five eggs are laid in the bird's nest, which is cup-shaped and well hidden. Adult sparrows are preyed upon by house cats and small raptors, while young may be taken by a range of mammals and reptiles. They have been known to live for up to three years, two months. Although the species has been classified as least concern, or unthreatened with extinction, some subspecies are threatened by habitat destruction and one may be extinct.

Taxonomy

This bird belongs to the family Emberizidae, which consists of the American sparrows and Eurasian buntings. The American sparrows are seed-eating New World birds with conical bills, brown or gray plumage, and distinctive head patterns. Birds in the genus Aimophila tend to be medium-sized at 5 to 8 inches (13 to 20 cm) in length, live in arid scrubland, have long bills and tails in proportion to their body size as well as short, rounded wings, and build cup-shaped nests.[4][5]

The rufous-crowned sparrow was described in 1852 by American ornithologist John Cassin as Ammodramus ruficeps.[2] It has also been described as belonging to the genus Peucaea, which contains several sparrows in the genus Aimophila that share characteristics, such as a larger bill and a patch of yellow under the bend of the wing, that other members of the genus do not.[3][6] However, splitting the Peucaea sparrows into a separate genus is not generally recognized.[2][7] A 2008 phylogenetic analysis of the genus Aimophila divided it into four genera, with the rufous-crowned sparrow and its two closest relatives, the Oaxaca sparrow and rusty sparrow, being maintained as the genus Aimophila.[8] In addition, this study suggested that the rufous-crowned sparrow may be more closely related to the brown towhees of the genus Pipilo than the other members of the historical genus Aimophila.[8]

The derivation of the current genus name, Aimophila, is from the Greek aimos/ἀιμος, meaning "thicket", and -philos/-φιλος, meaning "loving".[9] The specific epithet is a literal derivation of the common name, derived from the Latin rufus, meaning "reddish" or "tawny", and -ceps, from caput, meaning "head".[10] The bird is also occasionally referred to colloquially as the rock sparrow because of its preference for rocky slopes.[11]

Subspecies

Twelve subspecies are generally recognized,[2] although sometimes up to eighteen are named.[7]

- A. r. ruficeps, the nominate subspecies, was described by Cassin in 1852.[12] It is found in the coastal ranges of California and on the western slopes of the Sierra Nevada.[13] This subspecies is darker and noticeably smaller than A. r. eremoeca and has distinct rufous-brown streaking on its upperparts.[2]

- A. r. canescens was described by American ornithologist W. E. Clyde Todd in 1922,[12] and it is found in southwestern California and northeast Baja California as far east as the base of the San Pedro Mártir.[13] While the species itself is listed as of least concern, this subspecies is listed as a "species of special concern" by the California Department of Fish and Wildlife, signifying that this population is threatened with extinction.[11] It appears to be extremely similar to A. r. ruficeps but is darker.[2]

- A. r. obscura, described by Donald R. Dickey and Adriaan van Rossem in 1923,[12] is found in the Channel Islands of California on Santa Cruz, Anacapa, and formerly on Santa Catalina.[11][13] While the Santa Catalina population has not been observed since 1863, the subspecies seems to have colonized Anacapa Island.[11] No records exist of them before 1940.[14] This subspecies is similar to A. r. canescens but is darker.[2]

- A. r. sanctorum was described by van Rossem in 1947.[12] It was found on the Todos Santos Islands off the coast of northwest Baja California.[13][15] This subspecies is believed to be extinct.[16][11] This is the darkest of the coastal subspecies, especially on its underbelly.[2]

- A. r. sororia was described by Robert Ridgway in 1898,[12] and is found in the mountains of southern Baja California, specifically the Sierra de la Laguna.[13] It is the palest of the coastal subspecies.[2]

- A. r. scottii, described by George Sennett in 1888,[12] is found from northern Arizona to New Mexico south to northeastern Sonora and northwestern Coahuila.[13] It appears to be a darker gray than A. r. eremoeca and has narrower and darker rufous streaks on its breast.[2]

- A. r. rupicola was described by van Rossem in 1946.[12] It is found in the mountains of southwestern Arizona.[13] It is similar in appearance to A. r. scottii but is darker and grayer on its back.[2]

- A. r. simulans was described by van Rossem in 1934,[12] and it is found in northwestern Mexico from southeastern Sonora and southwestern Chihuahua to Nayarit and northern Jalisco.[13] It has more rufous coloration on its back and is paler on its underbelly than A. r. scottii.[2]

- A. r. eremoeca was described by N. C. Brown in 1882.[12] It is found from southeastern Colorado to New Mexico, Texas, northern Chihuahua, and central Coahuila.[13] It has grayish upperparts and a dark breast.[2]

- A. r. fusca, described by Edward William Nelson in 1897,[12] is found in western Mexico from southern Nayarit to southwestern Jalisco, northern Colima, and Michoacan.[13] It is darker and more rufous on its upperparts than A. r. australis. It also possesses a darker rufous crown which does not show a gray stripe down the middle.[2]

- A. r. boucardi was described by Philip Sclater in 1867,[12] and it is found in eastern Mexico from southern Coahuila to San Luis Potosí, northern Puebla, and southern Oaxaca.[13] This subspecies is darker than A. r. eremoeca and has dull brown, not rufous, streaking on the chest.[2]

- A. r. australis, described by Edward William Nelson in 1897,[12] occurs in southern Mexico from Guerrero to southern Puebla and Oaxaca.[13] A. r. scottii is similar in appearance, but this subspecies is smaller and has a shorter bill.[2]

The other six subspecies that are occasionally recognized are A. r. extima and A. r. pallidissima, which were described by A. R. Phillips in 1966, A. r. phillipsi, which was described by J.P. Hubbard and Crossin in 1974, and A. r. duponti, A. r. laybournae, and A. r. suttoni, which were described by J.P. Hubbard in 1975.[7]

Description

The rufous-crowned sparrow is a smallish sparrow at 5.25 inches (13.3 cm) in length, with males tending to be larger than females.[2][5][12] It ranges from 15 to 23 g (0.53 to 0.81 oz) in weight and averages about 19 g (0.67 oz).[5] It has a brown back with darker streaks and gray underparts. Its wings are short, rounded, and brown and lack wingbars, or a line of feathers of a contrasting color in the middle of the bird's wing. The sparrow's tail is long, brown, and rounded. The face and supercilium (the area above the eye) are gray with a brown or rufous streak extending from each eye and a thick black streak on each cheek.[12] The crown ranges from rufous to chestnut, a feature which gives it its common name, and some subspecies have a gray streak running through the center of the crown.[2][4] The bill is yellow and cone-shaped.[12] The sparrow's throat is white with a dark stripe. Its legs and feet are pink-gray.[2] Both sexes are similar in appearance, but the juvenile rufous-crowned sparrow has a brown crown and numerous streaks on its breast and flanks during the spring and autumn.[12]

The song is a short, fast, bubbling series of chip notes that can accelerate near the end, and the calls include a nasal chur and a thin tsi.[2] When threatened or separated from its mate, the sparrow makes a dear-dear-dear call.[17]

Distribution and habitat

This bird is found in the southwestern United States and Mexico from sea level up to 9,800 feet (3,000 m), though it tends to be found between 3,000 and 6,000 feet (910 and 1,830 m).[2][11] It lives in California, southern Arizona, southern New Mexico, Texas, and central Oklahoma south along Baja California and in western Mexico to southern Puebla and Oaxaca. In the midwestern United States, the sparrow is found as far east as a small part of western Arkansas, and also in a small region of northeastern Kansas, its most northeastern habitat. The range of this species is discontinuous and is made up of many small, isolated populations.[11] The rufous-crowned sparrow is a non-migratory species, though the mountain subspecies are known to descend to lower elevations during severe winters.[11] Male sparrows maintain and defend their territories throughout the year.[11]

This sparrow is found in open oak woodlands and dry uplands with grassy vegetation and bushes. It is often found near rocky outcroppings. The species is also known from coastal scrublands and chaparral areas.[2] The rufous-crowned sparrow thrives in open areas cleared by burning.[11]

Ecology and behavior

The average territory size of rufous-crowned sparrows in the chaparral of California ranges from 2 acres (0.81 ha) to 4 acres (1.6 ha).[11] The density of territories varies by habitat, including 2.5 to 5.8 territories per 99 acres (40 ha) of three- to five-year-old burned chaparral to 3.9 to 6.9 territories for the same amount of coastal scrubland.[11] One pair tends to be supported by a territory, although birds without a mate have been seen sharing a territory with a mated pair.[11]

This sparrow is awkward in flight and primarily uses running and hopping to move.[5] The rufous-crowned sparrow will at times forage in pairs during the breeding season, and in family-sized flocks in late summer and early autumn. During the winter they can occasionally be found in loose mixed-species foraging flocks.[11]

Predators of adult sparrows include house cats and small raptors like Cooper's and sharp-shinned hawks, American kestrels, and white-tailed kites.[18] The nests may be raided by a range of species including mammals and reptiles such as snakes, though nest predation has not yet been directly observed, and nesting sparrows have been observed using three kinds of displays to distract potential predators; the rodent run, the broken wing, and the tumbling off the bush.[11] Birds adopt a rodent run display to distract predators. The head, neck and tail are lowered, wings held out, and feathers fluffed as the bird runs rapidly and voices a continuous alarm call.[19][20] In the broken wing display, the sparrow imitates having a broken wing by dropping one to the ground and hopping away from the nest with one wing dragging, leading the predator away until the bird ceases the act and escapes the predator.[21] The adult rufous-crowned sparrow distracts a nest predator by falling from the top of a bush to attract the predator to itself in the tumbling off the bush display.[22]

The longest lifespan recorded for a rufous-crowned sparrow is three years, two months.[5] Two species of tick, Amblyomma americanum and Ixodes pacificus, are known to parasitize the sparrow.[5]

Diet

This sparrow feeds primarily on small grass and forb seeds, fresh grass stems, and tender plant shoots during autumn and winter.[11] During these seasons, insects such as ants, grasshoppers, ground beetles, and scale insects as well as spiders make up a small part of its diet. In the spring and summer, the bird's diet includes a greater quantity and variety of insects.[17]

The rufous-crowned sparrow forages slowly on or near the ground by walking or hopping under shrubs or dense grasses.[11] Though it occasionally forages in weedy areas, it is almost never observed foraging in the open. It has occasionally been observed feeding in branches and low shrubs.[17] During the breeding season, it gleans its food from grasses and low shrubs.[11] However, normally the species obtains its food by either pecking or less frequently scratching at leaf litter. This bird tends to forage in a small family group and in a limited area.[17]

It is unknown whether this species obtains all of the water it needs from its food or if it must also drink; however, it has been observed both drinking and bathing in pools of water after rain storms.[11]

Reproduction

The rufous-crowned sparrow breeds in sparsely vegetated scrubland. Males attract a mate by singing from regular positions at the edge of their territories throughout the breeding season. These birds are monogamous, taking only one mate at a time, and pairs often remain together for several years.[11] If singing males come within contact of each other, they may initially raise their crowns and face the ground to display this feature; if that fails to make the other bird leave, they stiffen their body, droop their wings, raise their tails, and stick their head straight out.[11] Males guard their territories year-round.[11]

While it is not known when precisely the breeding season starts, the earliest that a sparrow has been observed carrying nesting material was on March 2 in southern California.[11] The female bird builds a bulky, thick-walled open-cup nest typically on the ground, though occasionally in a low bush up to 18 in (46 cm) above it, from dried grasses and rootlets, sometimes with strips of bark, small twigs, and weed stems.[5][11] Nests are well hidden, as they are built near bushes or tall grasses or overhanging rock with concealing vegetation.[11] Once a sparrow chooses a nesting site, it tends to return to the site for many years.[11] It lays between two and five eggs at a time and typically only raises one brood a year, though some birds in California have been observed raising two or even three broods a year.[11][12] In case of a nesting failure, replacement clutches may be laid.[11] The eggs are an unmarked, pale bluish-white.[17] Broods of the rufous-crowned sparrow have very occasionally been observed to be parasitized by the brown-headed cowbird.[11][23]

Incubation of the eggs lasts 11 to 13 days and is performed solely by the female. The hatchlings are naked and quills do not begin to show until the third day. Only females brood the nestlings, though both parents may bring whole insects to their young. When a young rufous-crowned sparrow leaves the nest after eight or nine days, it is still incapable of flight, though it can run through the underbrush; during this time it is still fed by the parents. Juveniles tend to leave their parent's territory and move into adjacent habitat in autumn or early winter. Reproductive success varies strongly with annual rainfall and is highest in wet El Niño years, since cool rainy weather reduces the activity of snakes, the main predator of the sparrow's nests.[24]

Conservation

The rufous-crowned sparrow is treated as a species of least concern, or not threatened with extinction, by BirdLife International due to its large geographical range of about 463,323 sq mi (1,200,000 km2), estimated population of 2.4 million individuals, and lack of a 30% population decline over the last ten years.[25] In years without sufficient rains, many birds fail to breed and those that do produce fewer offspring.[18][26] Some of the local populations of this bird are threatened and declining in number.[11] The island subspecies and populations have declined in some cases: A. r. sanctorum of the Todos Santos Islands is believed to be extinct,[16] and the populations on Santa Catalina Island and Baja California's Islas de San Martin have not been observed since the early 1900s.[11] Populations of the species in southern California are also becoming more restricted in range because of urbanization and agricultural development in the region. Additionally, the sparrow is known to have been poisoned by the rodenticide warfarin, though more research is needed to determine the effects of pesticides on the rufous-crowned sparrow.[11]

References

- ↑ BirdLife International (2012). "Aimophila ruficeps". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. IUCN. 2012: e.T22721288A39944668. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2012-1.RLTS.T22721288A39944668.en. Retrieved 27 August 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 Byers, Clive; Curson, Jon; Olsson, Urban (1995). Sparrows and Buntings: A Guide to the Sparrows and Buntings of North America and the World. Pica Press. pp. 296–297. ISBN 1-873403-19-4.

- 1 2 Storer, Robert W. (1955). "A preliminary survey of the sparrows of the genus Aimophila" (PDF). The Condor. 57 (4): 193–201. doi:10.2307/1365082. JSTOR 1365082. Retrieved 13 February 2009.

- 1 2 Howell, Steve N.G.; Webb, Sophie (1995). A Guide to the Birds of Mexico and Northern Central America. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-854012-4.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Omari, Amel; Fraser, Ann (2007). "Aimophila ruficeps". Animal Diversity Web. Retrieved 12 April 2009.

- ↑ Wolf, Larry L. (1977). Species relationships in the avian genus Aimophila (PDF). Ornithological Monographs. American Ornithologists' Union.

- 1 2 3 "ITIS Standard Report Page: Aimophila ruficeps". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 12 April 2009.

- 1 2 DaCosta, Jeffrey M.; Spellman, Garth M.; Escalante, Patricia; Klicka, John (2009). "A molecular systematic review of two historically problematic songbird clades: Aimophila and Pipilo". Journal of Avian Biology. Copenhagen: Munksgaard International. 40 (2): 206–216. doi:10.1111/j.1600-048X.2009.04514.x.

- ↑ Holloway, J.E. (2003). Dictionary of Birds of the United States: Scientific and Common Names. Portland, Oregon: Timber Press. p. 17. ISBN 0-88192-600-0.

- ↑ Simpson, D.P. (1979). Cassell's Latin Dictionary (5th ed.). London: Cassell. p. 883. ISBN 0-304-52257-0.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 Thorngate, Nellie; Parsons, Monika (2005). "California Partners in Flight coastal scrub and chaparral bird conservation plan Rufous-crowned Sparrow (Aimophila ruficeps)". California Partners in Flight. Retrieved 19 January 2008.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 Gough, Gregory (28 December 2000). "Rufous-crowned sparrow Aimophila ruficeps". Patuxent Bird Identification InfoCenter. USGS Patuxent Wildlife Research Center. Retrieved 18 January 2007.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Clements, James F. (2007). The Clements Checklist of Birds of the World (6th ed.). Ithaca, NY: Comstock Publishing Associates. pp. 681–682. ISBN 978-0-8014-4501-9.

- ↑ Johnson, Ned K. (1972). "Origin and differentiation of the avifauna of the Channel Islands, California" (PDF). Condor. 74 (3): 295–315. doi:10.2307/1366591. JSTOR 1366591. Retrieved 13 February 2009.

- ↑ Howell, Alfred Brazier (June 1917). "Birds of the islands off the coast of southern California". Pacific Coast Avifauna. 12: 80. Retrieved 13 February 2009.

- 1 2 Donlan, C.J.; Tershy, B.R.; Keitt, B.S.; Wood, B.; Sanchez, J.A.; Weinstein, A.; Croll, D.A.; Alguilar, J.L. (2000). Browne, D.H.; Chaney, H.; Mitchell, K., eds. Island conservation action in northwest Mexico (PDF). Proceedings of the Fifth California Islands Symposium. Santa Barbara, California, USA: Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History. pp. 330–338. Retrieved 13 February 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Kaufman, Kenn (1996). Lives of North American Birds. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. p. 583. ISBN 0-618-15988-6.

- 1 2 Morrison, Scott A.; Bolger, Douglas T.; Sillett, Scott T. (2004). "Annual survivorship of the sedentary rufous-crowned sparrow (Aimophila ruficeps): no detectable effects of edge or rainfall in southern California". The Auk. 121 (3): 904–916. doi:10.1642/0004-8038(2004)121[0904:ASOTSR]2.0.CO;2.

- ↑ Rowley, Ian (1962). "'Rodent-run' distraction display by a passerine, the Superb Blue Wren Malurus cyaneus (L.)". Behaviour. 19: 170–176. doi:10.1163/156853961X00240. JSTOR 4533009.

- ↑ Barrows, Edward M. (2001). Animal Behavior Desk Reference (2nd ed.). CRC press. p. 177. ISBN 0-8493-2005-4.

- ↑ Hauser, Marc D. (1997). The Evolution of Communication. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. p. 588. ISBN 0-262-58155-8.

- ↑ Collins, Paul W. (1999). "Rufous-crowned Sparrow (Aimophila ruficeps)". In Poole, A.; Gill, F. The Birds of North America Online. Ithaca, NY: Cornell Lab of Ornithology. doi:10.2173/bna.472. Retrieved 11 April 2009.

- ↑ Miles, D.B. (1986). "A record of Brown-headed Cowbird Molothrus ater nest parasitism of Rufous-crowned Sparrows Aimophila ruficeps". Southwestern Naturalist. 31 (2): 253–254. doi:10.2307/3670570. JSTOR 3670570.

- ↑ Morrison, Scott A.; Bolger, Douglas T. (November 2002). "Variation in a sparrow's reproductive success with rainfall: food and predator-mediated processes". Oecologia. 133 (3): 315–324. doi:10.1007/s00442-002-1040-3. JSTOR 4223423.

- ↑ "Species factsheet: Aimophila ruficeps". BirdLife International. 2007. Retrieved 19 January 2008.

- ↑ Bolger, Douglas T.; Patten, Michael A.; Bostock, David C. (2005). "Avian reproductive failure in response to an extreme climatic event" (PDF). Oecologia. 142 (3): 398–406. doi:10.1007/s00442-004-1734-9. PMID 15549403. Retrieved 13 February 2009.

Further reading

- Baptista, L.F. (1973). "Leaf bathing in three species of emberizines" (PDF). Wilson Bulletin. 85 (3): 346–347.

- Behle, W.H. (1976). "Mojave Desert avifauna in the Virgin River Valley of Utah Nevada and Arizona USA" (PDF). Condor. 78 (1): 40–48. doi:10.2307/1366914. JSTOR 1366914.

- Bolger, D.T. (2002). "Habitat fragmentation effects on birds in southern California: Contrast to the "top-down" paradigm". Studies in Avian Biology. 25: 141–157.

- Bolger, D.T.; Scott, T.A.; Rotenberry, J.T. (1997). "Breeding bird abundance in an urbanizing landscape in coastal Southern California". Conservation Biology. 11 (2): 406–421. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1739.1997.96307.x.

- Borror, D.J. (1971). "Songs of Aimophila sparrows occurring in the United States" (PDF). Wilson Bulletin. 83 (2): 132–151.

- Carson, R.J.; Spicer, G.S. (2003). "A phylogenetic analysis of the emberizid sparrows based on three mitochondrial genes". Molecular Phylogenetics & Evolution. 29 (1): 43–57. doi:10.1016/S1055-7903(03)00110-6.

- Deviche, P.; McGraw, K.; Greiner, E.C. (2005). "Interspecific differences in hematozoan infection in Sonoran desert Aimophila sparrows". Journal of Wildlife Diseases. 41 (3): 532–541. doi:10.7589/0090-3558-41.3.532. PMID 16244063.

- Groschupf, K.D. (1983). Comparative study of the vocalizations and singing behavior of four Aimophila sparrows (Ph.D. thesis). Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University.

- Hardy, J.W. (1980). "The Oaxaca Sparrow Aimophila notosticta has a chatter vocalization". Condor. 82 (1): 111. doi:10.2307/1366802. JSTOR 1366802.

- Hubbard, J.P. (1975). "Geographic variation in non-California populations of the Rufous Crowned Sparrow". Nemouria. 15: 1–28.

- Morrison, S.A. (2001). Demography of a fragmentation-sensitive songbird: Edge and ENSO effects (Ph.D. thesis). Dartmouth College.

- Morrison, S.A.; Bolger, D.T. (2002). "Lack of an urban edge effect on reproduction in a fragmentation-sensitive sparrow". Ecological Applications. 12 (2): 398–411. doi:10.1890/1051-0761(2002)012[0398:LOAUEE]2.0.CO;2.

- Parker, S.A.; Stotz, D. (1977). "An observation on the foraging behavior of the Arizona Ridge-Nosed Rattlesnake Crotalus willardi willardi (Serpentes: Crotalidae)". Bulletin of the Maryland Herpetological Society. 13 (2): 123.

- Patten, M.A.; Bolger, D.T. (2003). "Variation in top-down control of avian reproductive success across a fragmentation gradient". Oikos. 101 (3): 479–488. doi:10.1034/j.1600-0706.2003.12515.x.

- Pulliam, H.R.; Mills, G.S. (1977). "The use of space by wintering sparrows". Ecology. 58 (6): 1393–1399. doi:10.2307/1935091. JSTOR 1935091.

- Remsen, J.V.J.; Cardiff, S. (1979). "First Records of the Race scottii of the Rufous-crowned Sparrow in California" (PDF). Western Birds. 10 (1): 45–46.

- Spicer, G.S. (1977). "Two new nasal mites of the genus Ptilonyssus Mesostigmata Rhinonyssidae from Texas USA". Acarologia. 18 (4): 594–601.

- Wimer, M.C. (1995). Song variation in insular and mainland Rufous-crowned Sparrows (M.S. thesis). Long Beach, California: California State University, Long Beach.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Aimophila ruficeps. |

| Wikispecies has information related to: Aimophila ruficeps |

- Audio recordings of Rufous-crowned sparrow on Xeno-canto.

- Rufous-crowned sparrow photo gallery at VIREO (Drexel University)

- "Rufous-crowned sparrow media". Internet Bird Collection.

- Old illustration of the "Brown-headed Finch" from Cassin's Birds of California and Texas

- "Aimophila ruficeps". Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Retrieved 24 February 2009.