Galois/Counter Mode

Galois/Counter Mode (GCM) is a mode of operation for symmetric key cryptographic block ciphers that has been widely adopted because of its efficiency and performance. GCM throughput rates for state of the art, high speed communication channels can be achieved with reasonable hardware resources.[1] The operation is an authenticated encryption algorithm designed to provide both data authenticity (integrity) and confidentiality. GCM is defined for block ciphers with a block size of 128 bits. Galois Message Authentication Code (GMAC) is an authentication-only variant of the GCM which can be used as an incremental message authentication code. Both GCM and GMAC can accept initialization vectors of arbitrary length.

Different block cipher modes of operation can have significantly different performance and efficiency characteristics, even when used with the same block cipher. GCM can take full advantage of parallel processing and implementing GCM can make efficient use of an instruction pipeline or a hardware pipeline. In contrast, the cipher block chaining (CBC) mode of operation incurs significant pipeline stalls that hamper its efficiency and performance.

Basic operation

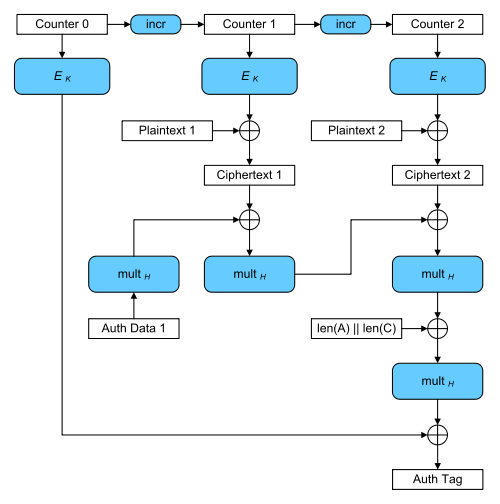

In the normal counter mode, blocks are numbered sequentially, and then this block number is encrypted with a block cipher E, usually AES. The result of this encryption is then xored with the plain text to produce a cipher text. Like all counter modes, this is essentially a stream cipher, and so it is essential that a different initialization vector is used for each stream that is encrypted.

The Galois Mult function then combines the ciphertext with an authentication code in order to produce an authentication tag that can be used to verify the integrity of the data. The encrypted text then contains the IV, cipher text, and authentication code. It therefore has similar security properties to a HMAC.

Mathematical basis

GCM combines the well-known counter mode of encryption with the new Galois mode of authentication. The key feature is that the Galois field multiplication used for authentication can be easily computed in parallel. This option permits higher throughput than the authentication algorithms, like CBC, that use chaining modes. The GF(2128) field used is defined by the polynomial

The authentication tag is constructed by feeding blocks of data into the GHASH function and encrypting the result. This GHASH function is defined by

where H is the Hash Key, a string of 128 zero bits encrypted using the block cipher, A is data which is only authenticated (not encrypted), C is the ciphertext, m is the number of 128 bit blocks in A, n is the number of 128 bit blocks in C (the final blocks of A and C need not be exactly 128 bits), and the variable Xi for i = 0, ..., m + n + 1 is defined as[2]

where v is the bit length of the final block of A, u is the bit length of the final block of C, denotes concatenation of bit strings, and len(A) and len(C) are the 64-bit representations of the bit lengths of A and C, respectively. Note that this is an iterative algorithm: each Xi depends on Xi−1 and only the final Xi is retained as output.

GCM mode was designed by John Viega and David A. McGrew as an improvement to Carter–Wegman Counter CWC mode.

In November 2007, NIST announced the release of NIST Special Publication 800-38D Recommendation for Block Cipher Modes of Operation: Galois/Counter Mode (GCM) and GMAC making GCM and GMAC official standards.[3]

Use

GCM mode is used in the IEEE 802.1AE (MACsec) Ethernet security, IEEE 802.11ad (also known as WiGig), ANSI (INCITS) Fibre Channel Security Protocols (FC-SP), IEEE P1619.1 tape storage, IETF IPsec standards,[4][5] SSH[6] and TLS 1.2.[7][8] AES-GCM is included in the NSA Suite B Cryptography. GCM mode is used in the SoftEther VPN server and client.[9]

Performance

GCM is ideal for protecting packetized data because it has minimum latency and minimum operation overhead.

GCM requires one block cipher operation and one 128-bit multiplication in the Galois field per each block (128 bit) of encrypted and authenticated data. The block cipher operations are easily pipelined or parallelized; the multiplication operations are easily pipelined and can be parallelized with some modest effort (either by parallelizing the actual operation, by adapting Horner's method as described in the original NIST submission, or both).

Intel has added the PCLMULQDQ instruction, highlighting its use for GCM.[10] This instruction enables fast multiplication over GF(2n), and can be used with any field representation.

Impressive performance results have been published for GCM on a number of platforms. Käsper and Schwabe described a "Faster and Timing-Attack Resistant AES-GCM"[11] that achieves 10.68 cycles per byte AES-GCM authenticated encryption on 64-bit Intel processors. Dai et al. report 3.5 cycles per byte for the same algorithm when using Intel's AES-NI and PCLMULQDQ instructions. Shay Gueron and Vlad Krasnov achieved 2.47 cycles per byte on the 3rd generation Intel processors. Appropriate patches were prepared for the OpenSSL and NSS libraries.[12]

When both authentication and encryption need to be performed on a message, a software implementation can achieve speed gains by overlapping the execution of those operations. Performance is increased by exploiting instruction level parallelism by interleaving operations. This process is called function stitching,[13] and while in principle it can be applied to any combination of cryptographic algorithms, GCM is especially suitable. Manley and Gregg[14] show the ease of optimizing when using function-stitching with GCM. They present a program generator that takes an annotated C version of a cryptographic algorithm and generates code that runs well on the target processor.

GCM has been criticized for example by Silicon Labs in the embedded world as the parallel processing is not suited to performant use of cryptographic hardware engines and therefore reduces the performance of encryption for some of the most performance sensitive devices.[15]

Patents

According to the authors' statement, GCM is unencumbered by patents.[16]

Security

GCM has been proven secure in the concrete security model.[17] It is secure when it is used with a block cipher that is indistinguishable from a random permutation; however, security depends on choosing a unique initialization vector for every encryption performed with the same key (see stream cipher attack). For any given key and initialization vector combination, GCM is limited to encrypting 239 − 256 bits of plain text (64 GiB). NIST Special Publication 800-38D[18] includes guidelines for initialization vector selection.

The authentication strength depends on the length of the authentication tag, as with all symmetric message authentication codes. The use of shorter authentication tags with GCM is discouraged. The bit-length of the tag, denoted t, is a security parameter. In general, t may be any one of the following five values: 128, 120, 112, 104, or 96. For certain applications, t may be 64 or 32, but the use of these two tag lengths constrains the length of the input data and the lifetime of the key. Appendix C in NIST SP 800-38D provides guidance for these constraints (for example, if t = 32 and the maximal packet size is 210 bytes, the authentication decryption function should be invoked no more than 211 times; if t = 64 and the maximal packet size is 215 bytes, the authentication decryption function should be invoked no more than 232 times).

As with any message authentication code, if the adversary chooses a t-bit tag at random, it is expected to be correct for given data with probability 2−t. With GCM, however, an adversary can choose tags that increase this probability, proportional to the total length of the ciphertext and additional authenticated data (AAD). Consequently, GCM is not well-suited for use with very short tag lengths or very long messages.

Ferguson and Saarinen independently described how an attacker can perform optimal attacks against GCM authentication, which meet the lower bound on its security. Ferguson showed that, if n denotes the total number of blocks in the encoding (the input to the GHASH function), then there is a method of constructing a targeted ciphertext forgery that is expected to succeed with a probability of approximately n⋅2−t. If the tag length t is shorter than 128, then each successful forgery in this attack increases the probability that subsequent targeted forgeries will succeed, and leaks information about the hash subkey, H. Eventually, H may be compromised entirely and the authentication assurance is completely lost.[19]

Independent of this attack, an adversary may attempt to systematically guess many different tags for a given input to authenticated decryption and thereby increase the probability that one (or more) of them, eventually, will be accepted as valid. For this reason, the system or protocol that implements GCM should monitor and, if necessary, limit the number of unsuccessful verification attempts for each key.

Saarinen described GCM weak keys.[20] This work gives some valuable insights into how polynomial hash-based authentication works. More precisely, this work describes a particular way of forging a GCM message, given a valid GCM message, that works with probability of about n⋅2−128 for messages that are n × 128 bits long. However, this work does not show a more effective attack than was previously known; the success probability in observation 1 of this paper matches that of lemma 2 from the INDOCRYPT 2004 analysis (setting w = 128 and l = n × 128). Saarinen also described a GCM variant Sophie Germain Counter Mode (SGCM), continuing the GCM tradition of including a mathematician in the name of the mode.

See also

References

- ↑ Lemsitzer, Wolkerstorfer, Felber, Braendli, Multi-gigabit GCM-AES Architecture Optimized for FPGAs. CHES '07: Proceedings of the 9th international workshop on Cryptographic Hardware and Embedded Systems, 2007.

- ↑ McGrew, David A.; Viega, John (2005). "The Galois/Counter Mode of Operation (GCM)" (PDF). p. 5. Retrieved 20 July 2013. Note that there is a typo in the formulas in the article.

- ↑ Dworkin, Morris (2007–2011). Recommendation for Block Cipher Modes of Operation: Galois/Counter Mode (GCM) and GMAC (PDF) (Technical report). NIST. 800-38D. Retrieved 2015-08-18.

- ↑ RFC 4106 The Use of Galois/Counter Mode (GCM) in IPsec Encapsulating Security Payload (ESP)

- ↑ RFC 4543 The Use of Galois Message Authentication Code (GMAC) in IPsec ESP and AH

- ↑ RFC 5647 AES Galois Counter Mode for the Secure Shell Transport Layer Protocol

- ↑ RFC 5288 AES Galois Counter Mode (GCM) Cipher Suites for TLS

- ↑ RFC 6367 Addition of the Camellia Cipher Suites to Transport Layer Security (TLS)

- ↑ https://www.softether.org/1-features

- ↑ http://software.intel.com/en-us/articles/intel-carry-less-multiplication-instruction-and-its-usage-for-computing-the-gcm-mode

- ↑ Cryptographic Hardware and Embedded Systems – CHES 2009, Lecture Notes in Computer Science 5745, Springer-Verlag (2009), pp. 1–17.

- ↑ Gueron, Shay. "AES-GCM for Efficient Authenticated Encryption – Ending the Reign of HMAC-SHA-1?" (PDF). Workshop on Real-World Cryptography. Retrieved 8 February 2013.

- ↑ Gopal, V., Feghali, W., Guilford, J., Ozturk, E., Wolrich, G., Dixon, M., Locktyukhin, M., Perminov, M.: Fast Cryptographic Computation on Intel Architecture Via Function Stitching Intel Corp. (2010)

- ↑ Raymond Manley, David Gregg, "A Program Generator for Intel AES-NI Instructions", INDOCRYPT 2010

- ↑ http://community.silabs.com/t5/Official-Blog-of-Silicon-Labs/IoT-Security-Part-6-Galois-Counter-Mode/ba-p/169191

- ↑ http://csrc.nist.gov/groups/ST/toolkit/BCM/documents/proposedmodes/gcm/gcm-nist-ipr.pdf

- ↑ The Security and Performance of the Galois/counter mode (GCM) of Operation, Proceedings of INDOCRYPT 2004, LNCS 3348 (2004)

- ↑ Morris Dworkin, Recommendation for Block Cipher Modes of Operation: Galois/Counter Mode (GCM) and GMAC, 2007-11

- ↑ Niels Ferguson, Authentication Weaknesses in GCM, 2005-05-20

- ↑ Markku-Juhani O. Saarinen (2011-04-20). "Cycling Attacks on GCM, GHASH and Other Polynomial MACs and Hashes". FSE 2012.

External links

- NIST Special Publication SP800-38D defining GCM and GMAC

- RFC 4106: The Use of Galois/Counter Mode (GCM) in IPsec Encapsulating Security Payload (ESP)

- RFC 4543: The Use of Galois Message Authentication Code (GMAC) in IPsec ESP and AH

- RFC 5288: AES Galois Counter Mode (GCM) Cipher Suites for TLS

- RFC 6367: Addition of the Camellia Cipher Suites to Transport Layer Security (TLS)

- IEEE 802.1AE – Media Access Control (MAC) Security

- IEEE Security in Storage Working Group developed the P1619.1 standard

- INCITS T11 Technical Committee works on Fibre Channel – Security Protocols project.

- AES-GCM and AES-CCM Authenticated Encryption in Secure RTP (SRTP)