Zhu Yu (author)

Zhu Yu (Chinese: 朱彧; Wade–Giles: Chu Yü) was an author of the Chinese Song Dynasty (960–1279 AD). He retired in Huang Gang(黄岗) of the Hubei province, bought a country house and named it "Pingzhou". He called himself "Expert Vegetable Grower of Pingzhou (萍洲老圃)". Between 1111 and 1117 AD, Zhu Yu wrote the book Pingzhou Ketan (萍洲可談; Pingzhou Table Talks), published in 1119 AD.[1] It covered a wide variety of maritime subjects and issues in China at the time. His extensive knowledge of maritime engagements, technologies, and practices were because his father, Zhu Fu, was the Port Superintendent of Merchant Shipping for Guangzhou from 1094 until 1099 AD, whereupon he was elevated to the status of governor there and served in that office until 1102 AD.[1][2]

Pingzhou Table Talks

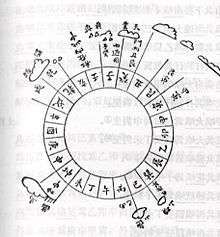

In terms of global significance, Zhu Yu's book was the first book in history to mention the use of the mariner's magnetic-needle compass for navigation at sea.[3] Although the compass needle was first described in detail by the Chinese scientist Shen Kuo (1031–1095) in his Dream Pool Essays of 1088 AD, he did not specifically outline its use for navigation at sea. The passage from Zhu Yu's Pingzhou Ketan relating to the use of the compass states:

According to government regulations concerning seagoing ships, the larger ones can carry several hundred men, and the smaller ones may have more than a hundred men on board. One of the most important merchants is chosen to be Leader (Gang Shou), another is Deputy Leader (Fu Gang Shou), and a third is Business Manager (Za Shi). The Superintendent of Merchant Shipping gives them an unofficially sealed red certificate permitting them to use the light bamboo for punishing their company when necessary. Should anyone die at sea, his property becomes forfeit to the government...The ship's pilots are acquainted with the configuration of the coasts; at night they steer by the stars, and in the day-time by the sun. In dark weather they look at the south-pointing needle (i.e. the magnetic compass). They also use a line a hundred feet long with a hook at the end which they let down to take samples of mud from the sea-bottom; by its (appearance and) smell they can determine their whereabouts.[2]

Although Zhu began writing his book in 1111 AD, it referred to events concerning various seaports of China from the year 1086 onwards.[2] Therefore, it is plausible that since the time that Shen Kuo began writing his book, the compass needle was being used for navigation.

Beyond the compass, Zhu's book described many other maritime subjects. Zhu Yu's book described the use of the for-and-aft lug, taut mat sails, and the practice of beating-to-windward.[4] Zhu also described bulkhead builds in the hulls of Chinese ships for creating watertight compartments.[4] Therefore, if a ship's hull was heavily damaged, only one compartment would fill with water while the ship could be salvaged without sinking.[5] Zhu Yu wrote that ships springing a leak could hardly be repaired from the inside, though; instead the Chinese employed expert foreign divers (people from the "Kunlun Mountains" region) that would dive into the water with chisels and oakum and mend the damage from the outside.[6] Expert divers were written of by many Chinese authors, including Song Yingxing (1587–1666) who wrote about pearl divers that used watertight leather face masks attached with breathing tubes secured with tin rings that led up to the surface, allowing them to breathe underwater for long periods of time.[7] Since at least the Tang Dynasty (618–907 AD), the Chinese also had a formula for a waterproof cream applied to silk clothes that proved useful for divers.[8]

Confirming Zhu Yu's writing on Song Dynasty ships with bulkhead hull compartments, in 1973 a 24 m (78 ft) long, 9 m (29 ft) wide Song Dynasty trade ship from circa 1277 AD was dredged from the water off the southern coast of China; this ship contained 12 bulkhead compartment rooms within its hull.[9]

See also

- Chinese literature

- History of the Song Dynasty

- Technology of the Song Dynasty

- Wujing Zongyao

- South-pointing chariot

- Alexander Neckam

Notes

References

- Ebrey, Walthall, Palais, (2006). East Asia: A Cultural, Social, and Political History. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company.

- Needham, Joseph (1986). Science and Civilization in China: Volume 4, Physics and Physical Technology, Part 1, Physics. Taipei: Caves Books Ltd.

- Needham, Joseph (1986). Science and Civilization in China: Volume 4, Physics and Physical Technology, Part 3, Civil Engineering and Nautics. Taipei: Caves Books Ltd.

- Needham, Joseph (1986). Science and Civilization in China, Volume 5, Chemistry and Chemical Technology, Part 4, Spagyrical Discovery and Invention: Apparatus, Theories and Gifts. Taipei: Caves Books Ltd.

- Sivin, Nathan (1995). Science in Ancient China: Researches and Reflections. Brookfield, Vermont: VARIORUM, Ashgate Publishing.