Yasna

| Part of a series on |

| Zoroastrianism |

|---|

Atar (fire), a primary symbol of Zoroastrianism. |

| Primary topics |

| Angels and demons |

| Scripture and worship |

|

| Accounts and legends |

| History and culture |

| Adherents |

|

|

Yasna is the Avestan language name of Zoroastrianism's principal act of worship, and it is also the name of the primary liturgical collection of Avesta texts, recited during that yasna ceremony.

The function of the yasna ceremony is, very roughly described, to strengthen the orderly spiritual and material creations of Ahura Mazda against the assault of the destructive forces of Angra Mainyu. The yasna service, that is, the recitation of the Yasna texts, culminates in the apæ zaothra, the "offering to the waters." The ceremony may also be extended by recitation of the Visperad and Vendidad texts. A normal yasna ceremony, without extensions, takes about two hours when it is recited by an experienced priest.

The Yasna texts constitute 72 chapters altogether, composed at different times and by different authors. The middle chapters include of the (linguistically) oldest texts of the Zoroastrian canon. These very ancient texts, in the very archaic and linguistically difficult Old Avestan language, include the four most sacred Zoroastrian prayers, and also 17 chapters comprising the five Gathas, hymns that are considered to have been composed by Zoroaster himself. Several sections of the Yasna include exegetical comments. Yasna chapter and verse pointers are traditionally abbreviated with Y.

The Avestan language word yasna literally means 'oblation' or 'worship'. The word is linguistically (but not functionally) equivalent to Vedic Yajna. Unlike Vedic Yajna, Zoroastrian Yasna has "to do with water rather than fire."[1][2]

The service

The theological function of the yasna ceremony, and the proper performance of it, is to further asha, that is, the ceremony aims to strengthen that which is right/true (one meaning of asha) in the existence/creation (another meaning of asha) of divine order (yet another meaning of asha). The Encyclopedia Iranica summarizes the aim of the yasna ceremony as "the maintenance of the cosmic integrity of the good creation of Ahura Mazdā."[3] Zoroastrianism's cosmological/eschatological perception of the purpose of humankind is to strengthen the orderly spiritual and material creations of Mazda against the assault of the destructive forces of Angra Mainyu. In that conflict, theologically speaking, mankind's primary weapon is the yasna ceremony, which is understood to have a direct, immediate effect: "[f]ar from being a symbolic act, the proper performance of the yasna is what prevents the cosmos from falling into chaos."[3] The culminating act of the yasna ceremony is the Ab-Zohr, the "strengthening of the waters".

The Yasna service, that is, the recitation of the Yasna texts, culminates in the Ab-Zohr, the "offering to waters". The Yasna ceremony may be extended by recitation of the Visperad and Vendidad.

A well-trained priest is able to recite the entire Yasna in about two hours.[4] With extensions, it takes about an hour longer. In its normal form, the Yasna ceremony is only to be performed in the morning.

The liturgy

Structure and organization

| The texts of the Yasna are organized into 72 chapters, known as hads or has (from Avestan ha'iti, 'cut'). The 72 threads of the Zoroastrian Kusti the sacred girdle worn around the waist - represent the 72 chapters of the Yasna.

From a literary point of view, the 72 chapters consist of two nested inner cores, and an outer envelope. The outer chapters/sections (the "envelope") are in the Younger Avestan language. The middle 27 chapters include the (linguistically) oldest texts of the Zoroastrian canon. The inner chapters/sections (excepting chapters 42.1-4,52.5-8) are in the more archaic Old Avestan language, with the four sacred formulae bracketing the innermost core. This innermost core includes the 17 chapters of the Gathas, the oldest and most sacred texts of the Zoroastrian canon.

From a ritual point of view, the liturgy can be broken into 4 major sections, each having its own internal prelude:

Some sections of the Yasna occur more than once. For instance, Yasna 5 is repeated as Yasna 37, and Yasna 63 consists of passages from Yasna 15.2, 66.2 and 38.3. The ability to recite the Yasna from memory is one of the prerequisites for Zoroastrian priesthood. |

Content summaries

- Yasna 1 opens with the praise of Ahura Mazda, enumerating his divine titles as the Creator, "radiant, glorious, the greatest, the best, the most beautiful, the most firm, the most wise, of the most perfect form, the highest in righteousness, possessed of great joy, creator, fashioner, nourisher, and the Most Holy Spirit." (Dhalla, 1936:155). Yasna 1 then enumerates the divinities, inviting them to the service.

- Yasna 2, the Barsom Yasht, presents libation and the barsom (a bundle of 23 twigs bound together, symbolizing sanctity) to the invited divinities. Yasna 2-4 complement Yasna 1. Most verses in Yasna 2-3 begin with the formula ayese yeshti …, "by means of this sacrifice, I call …", followed by the name of the divinity being invoked.

- Yasna 3-8 known collectively as the Sarosh dron, presents other offerings (zaothra). Yasna 3 draws the attention of the divinities invoked in Yasna 1, and in Yasna 4, the offerings are consecrated to the divinities. Yasna 5 is repeated in Yasna 37. Yasna 6 is almost identical to the first 10 verses of Yasna 17.

- Yasna 9-11 is the Hom Yasht, a collection of accolades to the Haoma plant and its divinity.

- Yasna 12 constitutes the Fravarane, the Zoroastrian creed and declaration of faith. It is in "Artificial" Gathic Avestan, that is, it is stylistically and linguistically aligned with the language of the Gathas, but imperfectly. The last strophe of verse 7 as well as all of verses 8 and 9 are incorporated into the Kusti ritual.

- Yasna 13-18 are comparable to Yasna 1-8 in that they too are a collection of invocations to the divinities. Chapters 14-18 serve as an introduction to the Staota Yesniia of Yasna 19-59. The first 10 verses of Yasna 17, "to the fires, waters, plants", is almost identical to Yasna 6.

- Yasna 19-21, the Bhagan Yasht, are commentaries on the three 'high prayers' of Yasna 28-53.

- Yasna 22-26 is another set of invocations to the divinities.

- Yasna 27 has the prayers referred to by Yasna 19-21. These are:

- The Ahuna Vairya invocation (also known as the Yatha Ahu Vairyo), the most sacred of all Zoroastrian prayers.

- The Ashem Vohu

- The Yenghe hatam

- Yasna 28-53 include the (linguistically) oldest texts of the Zoroastrian canon. 17 of the 26 chapters make up the Gathas, the most sacred hymns of Zoroastrianism and thought to have been composed by Zoroaster himself. The Gathas are in verse. These are structurally interrupted by a) the Yasna Haptanghaiti ("seven-chapter Yasna", #35-41), which is as old as the Gathas but in prose, b) two short chapters (#42 and #52) that are not as old as the Gathas and Yasna Haptanghaiti.

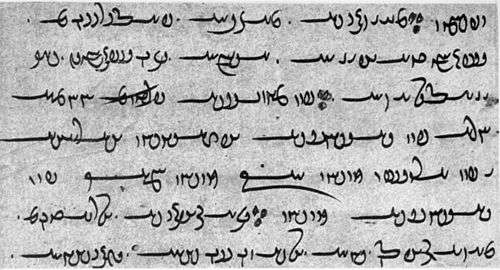

Yasna 28.1, Ahunavaiti Gatha (Bodleian MS J2)

Yasna 28.1, Ahunavaiti Gatha (Bodleian MS J2)- Yasna 28-34: Ahunavaiti Gatha

- Yasna 35-41: Yasna Haptanghaiti, the "seven-chapter Yasna", also in Gathic Avestan but in prose.

- Yasna 42: a 4 verse chapter invoking the elements.

- Yasna 43-46: Ushtavait Gatha

- Yasna 47-50: Spenta Mainyu Gatha

- Yasna 51: Vohu Khshathra Gatha

- Yasna 52: an 8 verse hymn to Ashi. Verses 52.5 - 52.8, in Younger Avestan, are a duplicate of Yasna 8.5 - 8.8.

- Yasna 53: Vahishto Ishti Gatha

- Yasna 54 has the text of the a airiiema ishiio, a prayer referred to in Yasna 27.

- Yasna 55 is a praise to the Gathas and the Staota Yesniia.

- Yasna 56 is again an invocation to the divinities, appealing for their attention.

- Yasna 57 is the Sarosh Yasht, the hymn to the divinity of religious discipline. It is closely related to, and appears to have sections borrowed from Yasht 10, the hymn to Mithra.

- Yasna 58 is again a "hidden" Yasht, here to the genius of prayer (cf. Dahman).

- Yasna 59 is a repetition of the sections from Yasna 17 and 26.

- Yasna 60 is blessing upon the house of the ashavan ('just' or 'true' man). Yasna 60.2-7 constitute the Dahma Afriti invocation, also known as the Afrinagan Dahman.

- Yasna 61 praises the anti-demonic powers imbued in the Afrinagan Dahman, Yenghe hatam and the three principal prayers of Yasna 27.

- Yasna 62 constitutes the Ataksh Nyashes, prayers to fire and its divinity.

- Yasna 63-69 constitute the prayers that accompany the Ab-Zohr, "offering to water".

- Yasna 70-72 are again a set of invocations to the divinities.

References

- Citations

- ↑ Drower 1944, p. 78.

- ↑ Boyce 1975, pp. 147-191.

- 1 2 Malandra 2006.

- ↑ Stausberg 2004, pp. 337,n131.

- Bibliography

- Boyce, Mary (1975), History of Zoroastrianism, I, Leiden: Brill, ISBN 90-04-10474-7.

- Boyce, Mary (1983), "Āb-Zōhr", Encyclopaedia Iranica, 1, Costa Mesa: Mazda Pub.

- Dhalla, Maneckji Nusservanji (1938), History of Zoroastrianism, Oxford University Press.

- Drower, Elizabeth Stephens (1944), Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, 74 (1/2): 75–89, doi:10.2307/2844296, JSTOR 2844296 Missing or empty

|title=(help);|chapter=ignored (help) - Kellens, Jean (1989), "Avesta", Encyclopaedia Iranica, 3, Costa Mesa: Mazda Pub, pp. 35–44.

- Kotwal, Firoze M.; Boyd, James W. (1991), The Yasna: A Zoroastrian High Liturgy, Cahiers de Studia Iranica, 8, Leuven: Peeters.

- Malandra, William (2006), "Yasna", Encyclopaedia Iranica, online edition, New York: iranicaonline.org.

- Stausberg, Michael (2004), Die Religion Zarathushtras (Band 3), Stuttgart: Kohlhammer, ISBN 3-17-017120-8.

Further reading

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

Translations of the Yasna liturgy now in the public domain:

- Mills, Lawrence Heyworth (1887), Avesta: Yasna, Sacred Books of the East, 31, Oxford University Press.

at avesta.org (organized by chapter). - Mills, American Edition, 1898, with select passages adopted from

Dhalla, Maneckji Nusservanji (1908), The Nyaishes Or Zoroastrian Litanies, Columbia University Press.

at sacred-texts.com (plain text).