Yarkant County

| Shache (Yarkant) County 莎车县 • يەكەن ناھىيىسى | |

|---|---|

| County | |

|

A street in Yarkant | |

.png) Yarkant County (red) within Kashgar Prefecture (yellow) and Xinjiang | |

Yarkant Location in Xinjiang | |

| Coordinates: 38°25′N 77°15′E / 38.417°N 77.250°ECoordinates: 38°25′N 77°15′E / 38.417°N 77.250°E | |

| Country | China |

| Region | Xinjiang |

| Prefecture | Kashgar |

| Area | |

| • Total | 8,969 km2 (3,463 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 1,232 m (4,042 ft) |

| Population (2002) | |

| • Total | 650,000 |

| • Density | 72/km2 (190/sq mi) |

| Time zone | China Standard (UTC+8) |

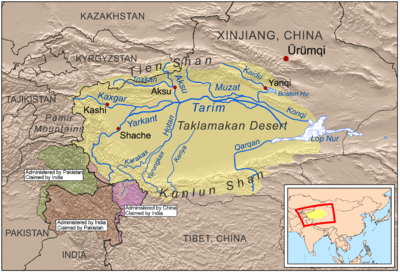

Shache (Yarkant) County or Yarkand County (lit. Cliff city[1]) is a county in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, China, located on the southern rim of the Taklamakan desert in the Tarim Basin. It is one of 11 counties administered under Kashgar Prefecture. Yarkant, usually written Yarkand in English, was the seat of an ancient Buddhist kingdom on the southern branch of the Silk Road. The county sits at an altitude of 1,189 metres (3,901 ft) and as of 2003 had a population of 373,492.

The fertile oasis is fed by the Yarkand River which flows north down from the Karakorum mountains and passes through Kunlun Mountains known historically as Congling mountains (lit. 'Onion Mountains' - from the abundance of wild onions found there). The oasis now covers 3,210 square kilometres (1,240 sq mi), but was likely far more extensive before a period of desiccation affected the region from the 3rd century CE onwards.

Today, Yarkant is a predominantly Uyghur settlement. The irrigated oasis farmland produces cotton, wheat, corn, fruits (especially pomegranates, pears and apricots), and walnuts. Yak and sheep graze in the highlands. Mineral deposits include petroleum, natural gas, gold, copper, lead, bauxite, granite and coal.

| Yarkant County | |||||||||||

|

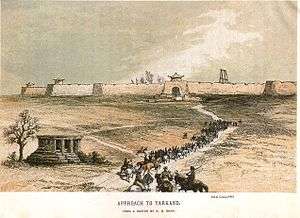

Street scene in Yarkand in the 1870s | |||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Chinese | 莎車縣 | ||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 莎车县 | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Uyghur name | |||||||||||

| Uyghur |

يەكەن ناھىيىسى | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

History

Han dynasty

The territory of Yārkand is first mentioned in the Book of Han (1st century BCE) as "Shache" (Old Chinese, approximately, *s³a(j)-ka), which is probably related to the name of the Iranian Saka tribes.[1]

Descriptions in the Hou Hanshu ('History of the Later Han') contain insights into the complex political situation China faced in attempting to open up the "Silk Routes" to the West in the 1st century CE. According to the "Chapter on the Western Regions" in the Hou Hanshu:

- "Going west from the kingdom of Suoju (Yarkand), and passing through the countries of Puli (Tashkurghan) and Wulei (centred on Sarhad in the Wakhan), you arrive among the Da Yuezhi (Kushans). To the east, it is 10,950 li (4,553 km) from Luoyang.

- The Chanyu (Khan) of the Xiongnu took advantage of the chaos caused by Wang Mang (9-24 CE) and invaded the Western Regions. Only Yan, the king of Suoju, who was more powerful than the others, did not consent to being annexed. Previously, during the time of Emperor Yuan (48-33 BCE), he was a hostage prince and grew up in the capital. He admired and loved the Middle Kingdom and extended the rules of Chinese administration to his own country. He ordered all his sons to respectfully serve the Han dynasty generation by generation, and to never turn their backs on it. Yan died in the fifth Tianfeng year (18 CE). He was awarded the posthumous title of 'Faithful and Martial King'. His son, Kang, succeeded him on the throne.

- At the beginning of Emperor Guangwu's reign (25-57 CE), Kang led the neighbouring kingdoms to resist the Xiongnu. He escorted, and protected, more than a thousand people including the officers, the soldiers, the wife and children of the former Protector General. He sent a letter to Hexi (Chinese territory west of the Yellow River) to inquire about the activities of the Middle Kingdom, and personally expressed his attachment to, and admiration for, the Han dynasty.

- In the fifth Jianwu year (29 CE) the General-in-Chief of Hexi, Dou Rong, following Imperial instructions, bestowed on Kang the titles of: “King of Chinese Suoju, Performer of Heroic Deeds Who Cherishes Virtue [and] Commandant-in-Chief of the Western Regions.” The fifty-five kingdoms were all made dependencies after that.

- In the ninth year (33 CE) Kang died. He was awarded the posthumous title of “Greatly Accomplished King.” His younger brother, Xian, succeeded him on the throne. Xian attacked and conquered the kingdoms of Jumi (Keriya) and Xiye (Karghalik). He killed both their kings, and installed two sons of his elder brother, Kang, as the kings of Jumi and Xiye.

- In the fourteenth year (38 CE), together with An, the king of Shanshan (the Lop Nor region), he sent envoys to the Imperial Palace to offer tribute. Following this, the Western Regions were (again) in communication with China. All the kingdoms to the east of the Congling (Pamirs) were dependent on Xian.

- In the seventeenth year (41 CE), Xian again sent an envoy to present offerings [to the Emperor], and to ask that a Protector General be appointed. The Son of Heaven questioned the Excellency of Works, Dou Rong, about this. He was of the opinion that Xian, and his sons and brothers who had pledged to serve the Han were truly sincere. Therefore, [he suggested that] it would be appropriate to give him higher rank to maintain order and security.

- The Emperor then, using the same envoy that Xian had sent to him, bestowed upon him the seal and ribbon of “Protector General of the Western Regions,” and gave him chariots, standards, gold, brocades and embroideries.

"Pei Zun, the Administrator of Dunhuang, wrote saying that foreigners should not be allowed to employ such great authority and that these decrees would cause the kingdoms to despair. An Imperial decree then ordered that the seal and ribbons of “Protector General” be recovered, and replaced with the seal and ribbon of “Great Han General.” Xian’s envoy refused to make the exchange, and (Pei) Zun took them by force.

- Consequently, Xian became resentful. Furthermore, he falsely named himself “Great Protector General,” and sent letters to all the kingdoms. They all submitted to him, and bestowed the title of Chanyu on him. Xian gradually became arrogant making heavy demands for duties and taxes. Several times he attacked Qiuci (Kucha) and the other kingdoms. All the kingdoms were anxious and fearful.

- In the winter of the twenty-first year (45 CE), eighteen kings, including the king of Nearer Jushi (Turpan), Shanshan, Yanqi (Karashahr), and others, sent their sons to enter the service of the Emperor and offered treasure. As a result, they were granted audience when they circulated weeping, prostrating with their foreheads to the ground, in the hope of obtaining a Protector General. The Son of Heaven, considering that the Middle Kingdom was just beginning to return to peace and that the northern frontier regions were still unsettled, returned all the hostage princes with generous gifts.

- At the same time, Xian, infatuated with his military power, wanted to annex the Western Regions, and greatly increased his attacks. The kingdoms, informed that no Protector General would be sent, and that the hostage princes were all returning, were very worried and frightened. Therefore, they sent a letter to the Administrator of Dunhuang to ask him to detain their hostage sons with him, so that they could point this out to the [king of] Suoju (Yarkand), and tell him that their young hostage sons were detained because a Protector General was to be sent. Then he [the king of Yarkand] would stop his hostilities. Pei Zun sent an official report informing the Emperor [of this proposal], which he approved.

- In the twenty-second year (46 CE Xian, aware that no Protector General was coming, sent a letter to An, king of Shanshan, ordering him to cut the route to the Han. An did not accept [this order], and killed the envoy. Xian was furious and sent soldiers to attack Shanshan. An gave battle but was defeated and fled into the mountains. Xian killed or captured more than a thousand men, and then withdrew.

- That winter (46 CE), Xian returned and attacked Qiuci (Kucha), killed the king, and annexed the kingdom. The hostage princes of Shanshan, and then Yanqi (Karashahr) and the other kingdoms, were detained a long time at Dunhuang and became worried, so they fled and returned [to their kingdoms].

- The king of Shanshan wrote a letter to the Emperor expressing his desire to return his son to enter the service of the Emperor, and again pleaded for a Protector General, saying that if a Protector General were not sent, he would be forced to obey the Xiongnu. The Son of Heaven replied:

- “We are not able, at the moment, to send out envoys and Imperial troops so, in spite of their good wishes, each kingdom [should seek help], as they please, wherever they can, to the east, west, south, or north.”

- Following this, Shanshan, and Jushi (Turpan/Jimasa) again submitted to the Xiongnu. Meanwhile, Xian became increasingly violent.

- The king of Guisai, reckoning that his kingdom was far enough away, killed Xian’s envoy. Xian then attacked and killed him. He appointed a nobleman from that country, Sijian, king of Guisai. Furthermore, Xian appointed his own son, Zeluo, to be king of Qiuci (Kucha). Xian, taking account of the youth of Zeluo, detached a part of the territory from Qiuci (Kucha) from which he made the kingdom of Wulei (Yengisar). He transferred Sijian to the post of king of Wulei, and appointed another noble to the post of king of Guisai.

- Several years later, the people of the kingdom of Qiuci (Kucha), killed Zeluo and Sijian, and sent envoys to the Xiongnu to ask them to appoint a king to replace them. The Xiongnu established a nobleman of Qiuci (Kucha), Shendu, to be king of Qiuci (Kucha), making it dependent on the Xiongnu.

- Because Dayuan (Ferghana) had reduced their tribute and taxes, Xian personally took command of several tens of thousands of men taken from several kingdoms, and attacked Dayuan (Ferghana). Yanliu, the king of Dayuan, came before him to submit. Xian took advantage of this to take him back to his own kingdom. Then he transferred Qiaosaiti, the king of Jumi (Keriya), to the post of king of Dayuan (Ferghana). Then Kangju (Tashkent plus the Chu, Talas, and middle Jaxartes basins) attacked him there several times and Qiaosaiti fled home [to Keriya] more than a year later. Xian appointed him king of Jumi (Keriya) and sent Yanliu back to Dayuan again, ordering him to bring the customary tribute and offerings.

- Xian also banished the king of Yutian (Khotan), Yulin, to be king of Ligui and set up his younger brother, Weishi, as king of Yutian.

- More than a year later Xian became suspicious that the kingdoms wanted to rebel against him. He summoned Weishi, and the kings of Jumi (Keriya), Gumo (Aksu), and Zihe (Shahidulla), and killed them all. He didn’t set up any more kings, he just sent generals to maintain order and guard these kingdoms. Rong, the son of Weishi, fled and made submission to the Han, who named him: “Marquis Who Maintains Virtue.” A general from Suoju (Yarkand), named Junde, had been posted to Yutian (Khotan), and tyrannised the people there who became indignant.

- In the third Yongping year (60 CE), during the reign of Emperor Ming, a high official of this country, called Dumo, had left town when he saw a wild pig. He wanted to shoot it, but the pig said to him: “Do not shoot me, I will undertake to kill Junde for you.” Following this, Dumo plotted with his brothers and killed Junde. However, another high official, Xiumo Ba, plotted, in his turn, with a Chinese man, Han Rong, and others, to kill Dumo and his brothers, then he named himself king of Yutian (Khotan). Together with men from the kingdom of Jumi (Keriya), he attacked and killed the Suoju (Yarkand) general who was at Pishan (modern Pishan or Guma). He then returned with the soldiers.

- Then Xian sent his Heir Apparent, and his State Chancellor, leading 20,000 soldiers from several kingdoms, to attack Xiumo Ba. [Xiumo] Ba came to meet them and gave battle, defeating the soldiers of Suoju (Yarkand) who fled, and more than 10,000 of them were killed.

- Xian again fielded several tens of thousands of men from several kingdoms, and personally led them to attack Xiumo Ba. [Xiumo] Ba was again victorious and beheaded more than half of the enemy. Xian escaped and fled, returning to his kingdom. Xiumo Ba advanced and encircled Suoju (Yarkand), but he was hit and killed by an arrow, and his soldiers retreated to Yutian (Khotan).

- Suyule, State Chancellor [of Khotan], and others, appointed Guangde, the son of Xiumo Ba’s elder brother, king. The Xiongnu, with Qiuci (Kucha) and the other kingdoms, attacked Suoju (Yarkand), but were unable to take it.

- Later, Guangde recognising of the exhaustion of Suoju (Yarkand), sent his younger brother, the Marquis who Supports the State, Ren, commanding an army, to attack Xian. As he had suffered war continuously, Xian sent an envoy to make peace with Guangde. Guangde's father had previously been detained for several years in Suoju (Yarkand). Xian returned Guangde's father and also gave one of his daughters in marriage and swore brotherhood to Guangde, so the soldiers withdrew and left.

- In the following year (61 CE), Qieyun, the Chancellor of Suoju (Yarkand), and others, worried by Xian's arrogance, plotted to get the town to submit to Yutian (Khotan). Guangde, the king of Yutian (Khotan), then led 30,000 men from several kingdoms to attack Suoju (Yarkand). Xian stayed in the town to defend it and sent a messenger to say to Guangde: “I have given you your father and a wife. Why are you attacking me?” Guangde replied to him: “O king, you are the father of my wife. It has been a long time since we met. I want us to meet, each of us escorted by only two men, outside the town wall to make an alliance.”

- Xian consulted Qieyun about this. Qieyun said to him: “Guangde, your son-in-law is a very close relation; you should go out to see him.” Xian then rashly went out. Guangde advanced and captured him. In addition, Qieyun and his colleagues let the soldiers of Yutian (Khotan) into the town to capture Xian’s wife and children. (Guangde) annexed his kingdom. He put Xian in chains, and took him home with him. More than a year later, he killed him.

- When the Xiongnu heard that Guangde had defeated Suoju (Yarkand), they sent five generals leading more than 30,000 men from fifteen kingdoms including Yanqi (Karashahr), Weili (Korla), and Qiuci (Kucha), to besiege Yutian (Khotan). Guangde asked to submit. He sent his Heir Apparent as a hostage and promised to give felt carpets each year. In winter, the Xiongnu ordered soldiers to take Xian’s son, Bujuzheng, who was a hostage with them, to appoint him king of Suoju (Yarkand).

- Guangde then attacked and killed [Bujuzheng], and put his younger brother, Qili, on the throne. This was in the third Yuanhe year (86 CE) of Emperor Zhang.

- At this time Chief Clerk Ban Chao brought the troops of several kingdoms to attack Suoju (Yarkand). He soundly defeated Suoju (Yarkand) so it submitted to Han."[2]

In 90 CE the Yuezhi or Kushans invaded the region with an army of reportedly 70,000 men, under their Viceroy, Xian, but they were forced to withdraw without a battle after Ban Chao instigated a "burnt earth" policy.[3]

After the Yuanchu period (114-120 CE), when the Yuezhi or Kushans placed a hostage prince on the throne of Kashgar:

- "... Suoju [Yarkand] followed by resisting Yutian [Khotan], and put themselves under Shule [Kashgar]. Thus Shule [Kashgar], became powerful and a rival to Qiuci [Kucha] and Yutian [Khotan]."[4]

- "In the second Yongjian year [127 CE] of the reign of Emperor Shun, [Ban] Yong once again attacked and subdued Yanqi [Karashahr]; and then Qiuci [Kucha], Shule [Kashgar], Yutian [Khotan], Suoju [Yarkand], and other kingdoms, seventeen altogether, came to submit. Following this, the Wusun [Ili River Basin and Issyk Kul], and the countries of the Congling [Pamir Mountains], put an end to their disruptions to communications with the west."[5]

In 130 CE, Yarkand, along with Ferghana and Kashgar, sent tribute and offerings to the Chinese Emperor.[6]

Later history

There is very little information on Yarkant's history for many centuries, apart from a couple of brief references in Tang dynasty (618-907) histories and it appears to have been of less note then than the oasis of Kharghalik (see Yecheng and Yecheng County) to its south.[7]

It was possibly captured by the Muslims soon after they subdued Kashgar in the early 10/11th century.

The area became the main base in the region for Chagatai Khan (died 1241), who inherited Kashgaria (and also much of the land between the Oxus (Amu Darya) and Jaxartes (Syr Darya) rivers) after his father, Genghis Khan, died in 1227.

Marco Polo described Yarkant in 1273, but said only that this "province" (of Kublai Khan's nephew, Kaidu, d. 1301) was, "five days' journey in extent. The inhabitants follow the law of Mahomet, and there are also some Nestorian Christians. They are subject to the Great Khan's nephew. It is amply stocked with the means of life, especially cotton."[8]

At the end of the 16th century Yarkant was incorporated into the Khanate of Kashgar and became its capital. The Jesuit Benedict Göez, who sought a route from the Mughal Empire to Cathay (which, according to his superiors, may or may not have been the same place as China), arrived in Yarkant with a caravan from Kabul in late 1603. He remained there for about a year, making a short trip to Khotan during that time. He reported:

- "Hiarchan [Yarkant], the capital of the kingdom of Cascar, is a mart of much note, both for the great concourse of merchants, and for the variety of wares. At this capital the caravan of Kabul merchants reaches its terminus; and a new one is formed for the journey to Cathay. The command of this caravan is sold by the king, who invests the chiefs with a kind of royal authority over the merchants for the whole journey. A twelvemonth passed away however before the new company was formed, for the way is long and perilous, and the caravan is not formed every year, but only when a large number arrange to join it, and when it is known that they will be allowed to enter Cathay."[9]

During his journey, Göez also noted the presence of large marble quarries in the area, leading him to write that amongst native travellers from Yarkant to Cathay:

- "no article of traffic is more valuable or more generally adopted as an investment for this journey than lumps of a certain transparent kind of marble called by the Chinese "jusce" (jade). They carry these to the Emperor of Cathay, attracted by the high prices which he deems it obligatory on his dignity to give ; and such pieces as the Emperor does not fancy they are free to dispose of to private individuals."[10]

Yarkent Khanate

Yarkent served as capital for the Yarkent Khanate also known as Yarkent State from the establishment of Yarkent Khanate to the fall (1514–1677).

Qing dynasty

The Qing dynasty gained control of the region in the middle of the 18th century.

By the 19th century, due to its active trade with Ladakh, and an influx of foreign merchants, it became "the largest and most populous of all the States of Káshghar."(Kashgar).[11] Yakub Beg (1820–1877) conquered Khotan, Aksu, Kashgar, and neighbouring towns with the help of the Russians in the 1860s. He made Yarkant his capital, where he received embassies from England in 1870 and 1873. The Qing dynasty defeated Yakub at Turpan in 1877 after which he committed suicide. Thus ended the Kingdom of Kashgaria, and the region returned to Qing Chinese control.

Chinese merchants and soldiers, foreigners like Russians, foreign Muslims, and other Turki merchants all engaged in temporary marriages with Turki (Uyghur) women, since a lot of foreigners lived in Yarkand, temporary marriage flourished there more than it did towards areas with fewer foreigners like areas towards Kucha's east.[12] The Earl of Dunmore wrote in 1894:

Almost every Chinaman in Yarkand, soldier or civilian, takes unto himself a temporary wife, dispensing entirely with the services of the clergy, as being superfluous, and most of the high officials also give way to the same amiable weakness, their mistresses being in almost all cases natives of Khotan, which city enjoys the unenviable distinction of supplying every large city in Turkestan with courtesans.When a Chinaman is called back to his own home in China proper, or a Chinese soldier has served his time in Turkestan and has to return to his native city of Pekin or Shanghai, he either leaves his temporary wife behind to shift for herself, or he sells her to a friend. If he has a family he takes the boys with him~—if he can afford it—failing that, the sons are left alone and unprotected to fight the battle of life, While in the case of daughters, he sells them to one of his former companions for a trifling sum.

The natives, although all Mahammadans, have a strong predilection for the Chinese, and seem to like their manners and customs, and never seem to resent this behaviour to their womankind, their own manners, customs, and morals (?) being of the very loosest description.[13][14]

Twentieth century

The Battle of Yarkand took place in Yarkant county, in April 1934. Ma Zhancang's Chinese Muslim army defeated the Turkic Uighur and Kirghiz army, and the Afghan volunteers sent by king Mohammed Zahir Shah, and exterminated them all. The emir Abdullah Bughra was killed and beheaded, his head was sent to Idgah mosque.[15][16]

Almost all the ancient buildings of the old city were destroyed during the Cultural Revolution (1966–1968) with only the central mosque, the main gate of the old palace and the royal cemetery surviving.[17]

Following riots around Yarkant in summer 2014, many scores of people, including Hans and Uyghurs, died, with estimates ranging from the state media total of 96 to over 1,000 according to some residents and Rebiya Kadeer, president of the Germany-based World Uyghur Congress (WUC).[18][19] In August 2015, it was reported by Chinese media that the amount of farmland per capita was increased, which would imply a sudden decrease in population, assuming farmland remained level.[20]

Geography

| Yarkant | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate chart (explanation) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Yarkant is strategically located about half way between Kashgar and Khotan, at the junction of a branch road north to Aksu. It also was the terminus for caravans coming from Kashmir via Ladakh and then over the Karakoram Pass to the oasis of Niya in the Tarim Basin.[21] The Xinjiang-Tibet Highway China National Highway 219, built in 1956 commences in Yecheng/Yarkant and heads south and west, across the Ladakh plateau and into central Tibet.

From Yarkant another important route headed southwest via Tashkurgan Town to the Wakhan corridor from where travellers could cross the relatively easy Baroghil Pass and Badakshan.

Climate

As with much of southern Xinjiang, Yarkant has a temperate zone, continental (Köppen BWk), with a mean total of only 53 millimetres (2.09 in) of precipitation per annum. As spring and autumn are short, winter and summer are the main seasons. The monthly daily average temperature ranges from −5.5 °C (22.1 °F) in January to 25.4 °C (77.7 °F) in July; the annual mean is 11.70 °C (53.1 °F). The diurnal temperature variation is not particularly large for a desert, averaging 13.4 °C (24.1 °F) annually. With monthly percent possible sunshine ranging from 56% in March to 75% in October, the county seat receives 2,860 hours of bright sunshine annually.

| Climate data for Yarkhant (1971−2000) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 0.6 (33.1) |

5.7 (42.3) |

14.2 (57.6) |

23.0 (73.4) |

27.3 (81.1) |

31.2 (88.2) |

32.7 (90.9) |

30.9 (87.6) |

26.7 (80.1) |

20.0 (68) |

10.8 (51.4) |

1.9 (35.4) |

18.8 (65.8) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −10.8 (12.6) |

−5.9 (21.4) |

1.6 (34.9) |

8.7 (47.7) |

13.0 (55.4) |

16.5 (61.7) |

18.6 (65.5) |

16.8 (62.2) |

11.5 (52.7) |

4.2 (39.6) |

−2.4 (27.7) |

−8.1 (17.4) |

5.3 (41.6) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 1.1 (0.043) |

1.8 (0.071) |

3.6 (0.142) |

4.3 (0.169) |

8.1 (0.319) |

9.6 (0.378) |

6.7 (0.264) |

9.5 (0.374) |

3.9 (0.154) |

2.3 (0.091) |

1.4 (0.055) |

.9 (0.035) |

53.2 (2.095) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 1.7 | 1.6 | 1.2 | 1.1 | 2.4 | 3.2 | 3.5 | 3.2 | 1.5 | .9 | .3 | 1.5 | 22.1 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 66 | 57 | 48 | 40 | 44 | 43 | 49 | 58 | 60 | 59 | 63 | 72 | 54.9 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 181.6 | 182.8 | 205.0 | 231.4 | 262.9 | 303.6 | 296.6 | 268.2 | 257.7 | 261.4 | 222.8 | 186.3 | 2,860.3 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 60 | 61 | 56 | 59 | 60 | 69 | 66 | 64 | 69 | 75 | 74 | 63 | 64.7 |

| Source: China Meteorological Administration | |||||||||||||

Transportation

Yarkant is served by China National Highway 315 and the Kashgar-Hotan Railway.

The closest airport is Kashgar Airport, located 192 km (119 mi) (a 4.5 hour drive) northwest of the city. It is served by flights to Ürümqi, Shanghai and Beijing.

See also

Footnotes

- 1 2 P. Lurje, “Yārkand”, Encyclopædia Iranica, online edition

- ↑ Hill (2015) Vol. I, pp. 39, 41.

- ↑ Chavannes, Édouard (1906). "Trois généraux Chinois de la dynastie des Han Orientaux." T'oung pao 7, pp. 232-233.

- ↑ Hill (2015) Vol. I, p. 43.

- ↑ Hill (2015), Vol. I, p. 11.

- ↑ Hill (2015) Vol. I, pp. 180-181.

- ↑ Stein, Aurel M. 1907. Ancient Khotan: Detailed report of archaeological explorations in Chinese Turkestan, 2 vols., p. 87. Clarendon Press. Oxford.

- ↑ The Travels of Marco Polo. Translated by Ronald Latham. Abaris Books, New York (1982), p. 66. ISBN 0-89835-058-1

- ↑ (From: The Travels of Benedict Göez)

- ↑ "Eastern Turkestan". Pall Mall Gazette. British Newspaper Archive. 8 June 1871. Retrieved 8 August 2014. (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ Forsyth (1875), p. 34.

- ↑ Ildikó Bellér-Hann (2008). Community Matters in Xinjiang, 1880-1949: Towards a Historical Anthropology of the Uyghur. BRILL. pp. 267–. ISBN 90-04-16675-0.

- ↑ Charles Adolphus Murray Earl of Dunmore (1894). The Pamirs: Being a Narrative of a Year's Expedition on Horseback and on Foot Through Kashmir, Western Tibet, Chinese Tartary, and Russian Central Asia. J. Murray. pp. 328–.

- ↑ Ildikó Bellér-Hann (2008). Community Matters in Xinjiang, 1880-1949: Towards a Historical Anthropology of the Uyghur. BRILL. pp. 267–. ISBN 90-04-16675-0.

- ↑ Andrew D. W. Forbes (1986). Warlords and Muslims in Chinese Central Asia: a political history of Republican Sinkiang 1911–1949. Cambridge, England: CUP Archive. pp. 123, 303. ISBN 0-521-25514-7. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ Christian Tyler (2004). Wild West China: the taming of Xinjiang. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press. p. 314. ISBN 0-8135-3533-6. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

- ↑ Dorje (2009), p. 453.

- ↑ http://www.rfa.org/english/news/uyghur/yarkand-08052014150547.html

- ↑ http://news.sky.com/story/1328589/rare-visit-to-town-at-centre-of-massacre-claims

- ↑ "心系群众实际困难 提高服务群众能力" (in (Chinese)). 9 August 2015. Archived from the original on 3 May 2016.

- ↑ "The Most Important Findings of Niya in Taklamakan". The Silk Road. Retrieved 2007-07-21.

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Yarkand. |

- Dorje, Gyurme (2009). Tibet Handbook. 4th Edition. Footprint, Bath, England. ISBN 978-1-906098-32-2.

- Sir Thomas Douglas Forsyth (1875). Report of a mission to Yarkund in 1873, under command of Sir T. D. Forsyth: with historical and geographical information regarding the possessions of the ameer of Yarkund. Printed at the Foreign department press. p. 573. Retrieved 2011-01-23.

- Forsyth, T. D. Report on A Mission to Yarkund in 1873. Foreign Department Press, Calcutta, 1875. Downloadable from: https://archive.org/details/reportamissiont00forsgoog.

- Gordon, T. E. 1876. The Roof of the World: Being the Narrative of a Journey over the high plateau of Tibet to the Russian Frontier and the Oxus sources on Pamir. Edinburgh. Edmonston and Douglas. Reprint: Ch’eng Wen Publishing Company. Taipei. 1971.

- Hill, John E. (2015). Through the Jade Gate - China to Rome: A Study of the Silk Routes 1st to 2nd Centuries CE. Volumes I and II. CreateSpace, Charleston, SC. ISBN 978-1500696702 and ISBN 978-1503384620.

- Hulsewé, A. F. P. and Loewe, M. A. N. 1979. China in Central Asia: The Early Stage 125 BC – AD 23: an annotated translation of chapters 61 and 96 of the History of the Former Han Dynasty. E. J. Brill, Leiden.

- Puri, B. N. Buddhism in Central Asia, Motilal Banarsidass Publishers Private Limited, Delhi, 1987. (2000 reprint).

- Shaw, Robert. 1871. Visits to High Tartary, Yarkand and Kashgar. Reprint with introduction by Peter Hopkirk, Oxford University Press, 1984. ISBN 0-19-583830-0.

- Stein, Aurel M. 1907. Ancient Khotan: Detailed report of archaeological explorations in Chinese Turkestan, 2 vols. Clarendon Press. Oxford.

- Stein, Aurel M. 1921. Serindia: Detailed report of explorations in Central Asia and westernmost China, 5 vols. London & Oxford. Clarendon Press. Reprint: Delhi. Motilal Banarsidass. 1980.

External links

- Introduction to Yarkent County, official website of Kashgar Prefecture government

- Yarkand Pictures

- Travels of Benedict Göez Washington University

- The Silk Road Seattle website contains many useful resources including a number of full-text historical works)