Yankee Doodle

| "Yankee Doodle" | |

|---|---|

| Roud #4501 | |

|

The first verse and refrain of Yankee Doodle, engraved on the footpath in a park. | |

| Song | |

| Published | 1780s |

| Composer(s) | Traditional |

| Language | English |

|

1. Yankee Doodle Variations

Performed by Carrie Rehkopf 1. Yankee Doodle

Choral version by United States Army Chorus |

| Problems playing these files? See media help. | |

"Yankee Doodle" is a well-known Anglo-American song, the early versions of which date back to the Seven Years' War and the American Revolution (1775–83).[1] It is often sung patriotically in the United States today and is the state anthem of Connecticut.[2] Its Roud Folk Song Index number is 4501.

The melody is thought to be much older than both the lyrics and the subject, going back to folk songs of numerous peoples of Medieval Europe.[3][4]

Origin

The tune of Yankee Doodle is thought to be much older than the words, and many peoples knew the melody, including those of England, France, Holland (modern Netherlands), Hungary, and Spain.[3] The earliest words of "Yankee Doodle" came from a Middle Dutch harvest song (which is thought to have followed the same tune), possibly dating back as far as 15th century Holland.[5][6] It contained mostly nonsensical and out-of-place words, both in English and Dutch: "Yanker, didel, doodle down, Diddle, dudel, lanther, Yanke viver, voover vown, Botermilk und tanther."[3][4][6] Farm laborers in Holland at the time received as their wages "as much buttermilk (Botermilk) as they could drink, and a tenth (tanther) of the grain".[4][6]

The term Doodle first appeared in English in the early seventeenth century[7] and is thought to be derived from the Low German (a language close to Dutch) dudel, meaning "playing music badly" or Dödel, meaning "fool" or "simpleton". The Macaroni wig was an extreme fashion in the 1770s and became contemporary slang for foppishness.[8] Dandies were men who placed particular importance upon physical appearance, refined language, and leisure hobbies. A self-made "Dandy" was a British middle-class man from the late 18th to early 19th century who impersonated an aristocratic lifestyle. They notably wore silk strip cloth, stuck feathers in their hats, and bore two fob watch accessories simultaneously (two pocket watches with chains)—"one to tell what time it was and the other to tell what time it was not".[9] This era was the height of "dandyism" in London, when men wore striped silks upon their return from the Grand Tour, along with a feather in the hat.

The macaroni wig was an extreme example of such dandyism, popular in England at the time. The term macaroni was used to describe a fashionable man who dressed and spoke in an outlandishly affected and effeminate manner. The term pejoratively referred to a man who "exceeded the ordinary bounds of fashion"[10] in terms of clothes, fastidious eating, and gambling.

In British conversation, the term "Yankee Doodle Dandy" implied unsophisticated misappropriation of high-class fashion, as though simply sticking a feather in one's cap would make one to be noble.[11] Peter McNeil, professor of fashion studies, claims that the British were insinuating that the colonists were low-class men lacking masculinity, emphasizing that the American men were womanly.[12]

Early versions

Traditions place its origin in a pre-Revolutionary War song originally sung by British military officers to mock the disheveled, disorganized colonial "Yankees" with whom they served in the French and Indian War, apparently written c. 1755 by British Army surgeon Dr. Richard Schuckburgh while campaigning in upper New York.[13] The British troops sang it to make fun of their stereotype of the American soldier as a Yankee simpleton who thought that he was stylish if he simply stuck a feather in his cap.[1]

It was also popular among the Americans as a song of defiance.[1] As per the American Library of Congress, the Americans added additional verses to the song, mocking the British troops and hailing the Commander of the Continental army George Washington. By 1881, Yankee doodle had turned from being an insult to being a song of national pride.[14]

One version of the Yankee Doodle lyrics is generally attributed to Dr. Shuckburgh.[15] According to one story, Dr. Shuckburgh wrote the song after seeing the appearance of Colonial troops under Colonel Thomas Fitch, the son of Connecticut Governor Thomas Fitch.[16] According to Etymology Online, "The current version seems to have been written in 1776 by Edward Bangs, a Harvard sophomore who also was a Minuteman."[17]

A bill was introduced to the House of Representatives on July 25, 1999 (as referenced as H. CON. RES. 143) recognizing Billerica, Massachusetts as "America's Yankee Doodle Town". After the Battle of Lexington and Concord, a Boston newspaper reported:

"Upon their return to Boston [pursued by the Minutemen], one [Briton] asked his brother officer how he liked the tune now, — 'Dang them', returned he, 'they made us dance it till we were tired' — since which Yankee Doodle sounds less sweet to their ears."

The earliest known version of the lyrics comes from 1755 or 1758, as the date of origin is disputed:[18]

- Brother Ephraim sold his Cow

- And bought him a Commission;

- And then he went to Canada

- To fight for the Nation;

- But when Ephraim he came home

- He proved an arrant Coward,

- He wouldn't fight the Frenchmen there

- For fear of being devoured.

(Note that the sheet music which accompanies these lyrics reads, "The Words to be Sung through the Nose, & in the West Country drawl & dialect.")

The Ephraim referred to here was Ephraim Williams, a popularly known colonel in the Massachusetts militia who was killed in the Battle of Lake George. He left his land and property to the founding of a school in Western Massachusetts, now known as Williams College.

The tune also appeared in 1762 in one of America's first comic operas The Disappointment, with bawdy lyrics about the search for Blackbeard's buried treasure by a team from Philadelphia.[19]

It has been reported that the British often marched to a version believed to be about a man named Thomas Ditson of Billerica, Massachusetts. Ditson was tarred and feathered for attempting to buy a musket in Boston in March 1775, although he later fought at Concord:

- Yankee Doodle came to town,

- For to buy a firelock,

- We will tar and feather him,

- And so we will John Hancock.

For this reason, the town of Billerica is the "home" of Yankee Doodle,[20][21]

Another pro-British set of lyrics believed to have used the tune was published in June 1775 following the Battle of Bunker Hill:[22]

- The seventeen of June, at Break of Day,

- The Rebels they supriz'd us,

- With their strong Works, which they'd thrown up,

- To burn the Town and drive us.

There is another version attributed to Edward Bangs, a student at Harvard College, who wrote a ballad with fifteen verses which circulated in Boston and surrounding towns in 1775 or 1776.[23] Yankee Doodle was also played at the British surrender at Saratoga in 1777.[24]

On February 6, 1788, Massachusetts ratified the Constitution by a vote of 186 to 168. To the ringing of bells and the booming of cannon, the delegates trooped out of Brattle Street Church. Before many days had passed, the citizens sang their convention song to the tune of "Yankee Doodle." Here are the lyrics to their song:

- The vention did in Boston meet,

- The State House could not hold 'em

- So then they went to Fed'ral Street,

- And there the truth was told 'em...

- And ev'ry morning went to prayer,

- And then began disputing,

- Till oppositions silenced were,

- By arguments refuting.

- Now politicians of all kinds,

- Who are not yet decided,

- May see how Yankees speak their minds,

- And yet are not divided.

- So here I end my Fed'ral song,

- Composed of sixteen verses;

- May agriculture flourish long

- And commerce fill our purses!

Full version

| |

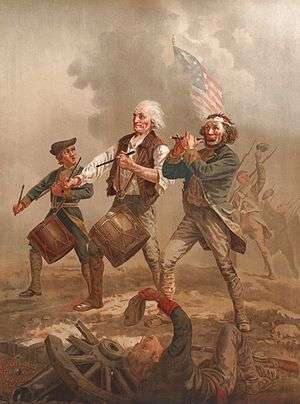

| Artist | Archibald MacNeal Willard |

|---|---|

| Year | circa 1875 |

| Type | oil |

| Dimensions | 61 cm × 45 cm (24 in × 18 in) |

| Location | United States Department of State |

The full version of the song, as it is known today, goes:[25][26]

- Yankee Doodle went to town

- A-riding on a pony,

- Stuck a feather in his cap

- And called it macaroni.

- [Chorus]

- Yankee Doodle keep it up,

- Yankee Doodle dandy,

- Mind the music and the step,

- And with the girls be handy.

- Father and I went down to camp,

- Along with Captain Gooding,

- And there we saw the men and boys

- As thick as hasty pudding.

- [Chorus]

- And there we saw a thousand men

- As rich as Squire David,

- And what they wasted every day,

- I wish it could be savéd.

- [Chorus]

- The 'lasses they eat every day,

- Would keep a house a winter;

- They have so much, that I'll be bound,

- They eat it when they've a mind to.

- [Chorus]

- And there I see a swamping gun

- Large as a log of maple,

- Upon a deuced little cart,

- A load for father's cattle.

- [Chorus]

- And every time they shoot it off,

- It takes a horn of powder,

- And makes a noise like father's gun,

- Only a nation louder.

- [Chorus]

- I went as nigh to one myself

- As 'Siah's underpinning;

- And father went as nigh again,

- I thought the deuce was in him.

- [Chorus]

- Cousin Simon grew so bold,

- I thought he would have cocked it;

- It scared me so I shrinked it off

- And hung by father's pocket.

- [Chorus]

- And Cap'n Davis had a gun,

- He kind of clapt his hand on't

- And stuck a crooked stabbing iron

- Upon the little end on't

- [Chorus]

- And there I see a pumpkin shell

- As big as mother's basin,

- And every time they touched it off

- They scampered like the nation.

- [Chorus]

- I see a little barrel too,

- The heads were made of leather;

- They knocked on it with little clubs

- And called the folks together.

- [Chorus]

- And there was Cap'n Washington,

- And gentle folks about him;

- They say he's grown so 'tarnal proud

- He will not ride without 'em.

- [Chorus]

- He got him on his meeting clothes,

- Upon a slapping stallion;

- He sat the world along in rows,

- In hundreds and in millions.

- [Chorus]

- The flaming ribbons in his hat,

- They looked so tearing fine, ah,

- I wanted dreadfully to get

- To give to my Jemima.

- [Chorus]

- I see another snarl of men

- A-digging graves, they told me,

- So 'tarnal long, so 'tarnal deep,

- They 'tended they should hold me.

- [Chorus]

- It scared me so, I hooked it off,

- Nor stopped, as I remember,

- Nor turned about till I got home,

- Locked up in mother's chamber.

- [Chorus]

Popular culture

- President John F. Kennedy from Massachusetts bought a pony for his daughter Caroline while he was in the White House. The family named it "Macaroni" after the song Yankee Doodle, although the name refers to the feathered cap rather than the pony.

Music

- Dueling Banjos, composed by Arthur "Guitar Boogie" Smith in 1955, contains riffs from Yankee Doodle.

- Alvin and the Chipmunks covered the song for their debut album Let's All Sing with The Chipmunks (1959).

Radio

- The Voice of America begins and ends all broadcasts with the interval signal of "Yankee Doodle".[27]

Sports

- TV commentator Bud Collins took note of the July 4th holiday and John McEnroe's red-white-and-blue attire at the conclusion of the 1981 Wimbledon Championships, in which American tennis star McEnroe had defeated his long-time rival Björn Borg: "Stick a feather in his cap and call him 'McEnroe-ni'!"[28]

- Hall of Fame racing jockey Tod Sloan's reputation was such that he was the "Yankee Doodle" in the George M. Cohan musical Little Johnny Jones, and the basis for Ernest Hemingway's short story My Old Man.

Television

- The PBS Kids show Barney and Friends adapts "Yankee Doodle" as its theme song.

- The children's cartoon series Roger Ramjet (1965) adapts "Yankee Doodle" as its theme song: "Roger Ramjet and his Eagles/Fighting for our freedom/Fly through in and outer space/Not to join 'em, but to beat 'em/Roger Ramjet, he's our man/Hero of our nation/For his adventures, just be sure/and stay tuned to this station". Ramjet's four child sidekicks, the "American Eagle Squadron", are named Yank, Doodle, Dan, and Dee.

- The title of the song has been parodied in the Looney Tunes Cartoons Yankee Doodle Daffy (1943) and Yankee Doodle Bugs (1954).

- The title of the song is parodied in a Tom and Jerry cartoon "Yankee Doodle Mouse" (1943).

- In a similar example to the John F. Kennedy one above, an episode of Julius Jr. featured Clancy's pony named Macaroni. This could be a reference to "Yankee Doodle".

- The song was used as title card music to the episode "Turner Back Time" of The Fairly OddParents.

- A Sesame Street parody of the song was done by music writer Don Music, who centered the song around cooking macaroni. In the song, Yankee Doodle stayed at home and cooked macaroni in a pot for his pony.

- Plastic Man sings the song in Batman: The Brave and the Bold

- The song is staged in a school presentation in "The Play's The Thing," the 8th episode of 6th season of Full House. Michelle Tanner wanted to play Yankee Doodle but her colleagues sang it better, so she got the part of the Statue of Liberty.

- In Turn: Washington's Spies season 3 episode 8 "Mended," the song is sung in parody by English Tories using alternate lyrics.

- For the KIA 2016 commercial featuring the Soul Hamsters, this tune is instrumentally fused with "Oh, Susanna".

Toys and games

- Two of the children's toys called Sing-a-ma-jigs sing this song.

- The Wii video game Wii Music features this song as a playable level.

- The video game Fallout 3 plays this song regularly on the Enclave's radio station.

- Wolfenstein 3D features a parody version of this song, mixed with a parody version of The Star-Spangled Banner, as a part of background music.

See also

Notes

- 1 2 3 Mooney, Mark (14 July 2014). "'Yankee Doodle Dandy' Explained and Other Revolutionary Facts". ABC News. Retrieved 6 May 2016.

- ↑ STATE OF CONNECTICUT, Sites º Seals º Symbols; Connecticut State Register & Manual; retrieved on May 23, 2008

- 1 2 3 Johnson, Helen Kendrick. "The Meaning of Song" in The North American Review vol.138, no.330 (1884): p.491. Retrieved 17 June 2016 from www

.jstor .org /stable /25118383 - 1 2 3 Banks, Louis Albert (1898). Immortal Songs of Camp and Field: The Story of Their Inspiration, Together with Striking Anecdotes Connected with Their History. Burrows Brothers Company. p. 44.

- ↑ Yankee Doodle Dandy, The New York Times

- 1 2 3 Elson, Louis Charles (1912). University Musical Encyclopedia: A history of music. 2. p. 82.

- ↑ "doodle", n, Oxford English Dictionary; accessed April 29, 2009.

- ↑ J. Woodforde, The Strange Story of False Hair (London: Taylor & Francis, 1971), p. 40.

- ↑ Grose, Francis; Egan, Pierce (1823). Grose's Classical Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue: Revised and Corrected with the Addition of Numerous Slang Phrases Collected from Tried Authorities. London.

- ↑ The Macaroni and Theatrical Magazine, inaugural issue, 1772, quoted in Amelia Rauser, "Hair, Authenticity, and the Self-Made Macaroni", Eighteenth-Century Studies 38.1 (2004:101-117) (on-line abstract).

- ↑ R. Ross, Clothing: a global history: or, The Imperialists' new clothes (Polity, 2008), p. 51.

- ↑ Peter McNeil, That Doubtful Gender: Macaroni Dress and Male Sexualities (Fashion Theory, 1998), pp. 411-48.

- ↑ See www.etymonline.com, "Yankee Doodle".

- ↑ "Historical Period: The American Revolution, 1763-1783 - Lyrical legacy - Yankee doodle song". http://www.loc.gov/teachers/lyrical/songs/yankee_doodle.html. Library of Congress. Retrieved 6 May 2016. External link in

|website=(help) - ↑ A. Lomax, John; Lomax, Alan. American ballads and f-28276-3. p. 521.

- ↑ Sonneck, Oscar George Theodore. Report on The Star-spangled Banner, Hail Columbia, America, Yankee Doodle. New York, Dover Publications [1972]. ISBN 0-486-22237-3.

- ↑ http://www.etymonline.com, "Yankee Doodle"

- ↑ Carola, Chris (July 5, 2008). "Wish 'Yankee Doodle' a happy 250th birthday. Maybe.". Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Associated Press. Retrieved 2009-09-10.

- ↑ Bobrick, 148

- ↑ The Billerica Colonial Minute Men; The Thomas Ditson story; retrieved January 31, 2013.

- ↑ Town History and Genealogy; retrieved October 20, 2008.

- ↑ "What's the song "Yankee Doodle" all about?". The Straight Dope. 2001-01-04. Retrieved 2016-08-31.

- ↑ The Boston Yankee Doodle Ballad; retrieved on July 3, 2010

- ↑ Luzader, John F. (2008). Saratoga: A Military History of the Decisive Campaign of the American Revolution. New York: Savas Beatie. p. 335. ISBN 978-1-932714-44-9.

- ↑ Gen. George P. Morris - "Original Yankee Words", The Patriotic Anthology, Doubleday, Doran & Company, Inc. publishers, 1941. Introduction by Carl Van Doren. Literary Guild of America, Inc., New York, NY.

- ↑ Penrhyn Wingfield Coussens, editor. Poems Children Love: A Collection of Poems Arranged for Children and Young People of Various Ages. Dodge Publishing Company, New York, 1908. pp. 183-5.

- ↑ Berg, Jerome S. (1999). On the Short Waves, 1923-1945: Broadcast Listening in the Pioneer Days of Radio. McFarland. p. 104. ISBN 0-7864-0506-6.

- ↑ "ESPN Classic — McEnroe was McNasty on and off the court". Espn.go.com. Retrieved 2009-09-10.

Further reading

- Bobrick, Benson (1997). Angel in the Whirlwind. Simon & Schuster, New York. ISBN 0-684-81060-3.

External links

| Wikisource has the text of the 1879 American Cyclopædia article Yankee Doodle. |

- Library of Congress Yankee Doodle music website

- The Boston Yankee Doodle Ballad

- The free score on www.traditional-songs.com

- Writings

- Report on "The Star-Spangled Banner," "Hail Columbia," "America," "Yankee Doodle" by Oscar George Theodore Sonneck (1909) 2 3 4

- Famous American songs (1906)

- Historical Audio

- Yankee Doodle (archive.org)