Women in space

.jpg)

This article addresses the subject of human females traveling above the Kármán line. This includes orbiting in the thermosphere through to travel in outer space.

Women of many nationalities have worked in space. The first woman in space, Soviet cosmonaut Valentina Tereshkova, flew in 1963. Space programs were slow to employ women, and only began to include them from the 1980s. Most women in space have been United States citizens, primarily with missions on the Space Shuttle. Three countries maintain active space programs that include women: China, Russia, and the United States of America. In addition, a number of other countries – Canada, France, India, Iran, Italy, Japan, South Korea, and the United Kingdom – have sent women into orbit or space on Russian or US missions.

Women in space face many of the same challenges faced by men: physical difficulties from non-Earth conditions and psychological stresses of isolation and separation. Scientific studies on female amphibians and non-human mammals generally show no adverse effect from short space missions, although the effect of extended space travel on female reproduction is not known.

As of July 2014, while 24 men have journeyed to the Moon, no woman has travelled beyond low earth orbit.

Women in space programs

A number of women have traveled into space. Although the first woman flew into space in 1963, very early in crewed space exploration, it would not be until almost 20 years later that another flew.

Soviet Union (includes Russia)

The first woman in space was a Soviet cosmonaut. Valentina Tereshkova launched with the Vostok 6 mission on June 16, 1963. The first woman to walk in space was also a cosmonaut: Svetlana Savitskaya was on her second mission when she spaced-walked on July 17, 1984 as part of Salyut 7-EP2

Post-Soviet Russia

Russian Yelena V. Kondakova became the first woman to travel for both the Soyuz programme and the Space Shuttle. Yelena Serova became the first female Russian cosmonaut to visit the International Space Station on 26 September 2014.[1]

The Russian space program has also hosted international cosmonauts. Helen Sharman from the United Kingdom (1991), Claudie Haigneré from France (1996 and 2001), Anousheh Ansari from Iran (2006), Yi So-yeon of South Korea (2008) and Samantha Cristoforetti from Italy (2014) and six Amen have entered space as part of the Soyuz programme.

United States

The United States did not have a woman in space until 1983, when astronaut Sally Ride launched with the seventh Space Shuttle mission. Since then more than 40 American women have entered space. Most served on the various Space Shuttle flights from 1983 to 2010.

In addition, US rockets have launched international astronauts. Roberta Bondar and Julie Payette from Canada (in 1992 and 1999/2009), Kalpana Chawla of India (1997 and 2003), and Chiaki Mukai and Naoko Yamazaki of Japan (1994/1998 and 2010) flew as part of the US space program.

A number of other high-profile women have contributed to interest in space programs. In the early 2000s, Lori Garver initiated a project to increase the visibility and viability of commercial spaceflight with the "AstroMom" project. She aimed to fill an unused Soyuz seat bound for the International Space Station because "…creating a spacefaring civilization was one of the most important things we could do in our lifetime.”[2]

The United State's experienced the first loss of woman astronauts in 1986;Judith A. Resnick and Christa McAuliffe perished in the Space Shuttle Challenger disaster. McAuliffe was to be the first U.S. civilian and school teacher in space.[3]

China

In 2012, China became the fourth nation to send women into space. (The others are Russia, the former Soviet Union, and the United States.)

China's first female astronaut candidates, chosen in 2010 from the ranks of fighter pilots, were required to be married mothers.[4] The Chinese stated that married women were "more physically and psychologically mature" and that the rule that they had have had children was because of concerns that spaceflight would harm their reproductive organs (which includes unfertilized embryos).[4] The unknown nature of the effects of spaceflight on women was also noted.[4] However, the director of the China Astronaut Centre has stated that marriage is a preference but not a strict limitation.[5] Part of they they were so strict was because it was their first astronaught selection and they were trying be "extra cautious".[4] China's first woman astronaut, Liu Yang, was married but had no children at the time of her flight in June 2012.[6][7]

Canada

Roberta Bondar was the first Candadian in space and she received many honours including the Order of Canada, the Order of Ontario, the NASA Space Medal, over 22 honorary degrees and induction into the Canadian Medical Hall of Fame.[8]

Another Canadian woman astronaut is Julie Payette from Montreal, and she flew on Space Shuttle Discovery from May 27 to June 6, 1999, as part of the crew of STS-96. During the mission, the crew performed the first manual docking of the Shuttle to the International Space Station, and delivered four tons of logistics and supplies to the station. On Discovery, Payette served as a mission specialist. Her main responsibility was to operate the Canadarm robotic arm from the space station.[9] The

Mothers in orbit

Examples

Many human mothers have traveled in space. Anna Fisher became the first when she flew into orbit aboard Discovery with mission STS-51-A on November 8, 1984.[10][11] (Yuri Gagarin was already a father at the time of Vostok 1, his historic first flight.[12])

Valentina Tereshkova was the first female in space to become a mother (after her flight). Shannon Lucid was already a mother when selected in 1978 to be an astronaut.[13] She remembers being questioned by the press at that time on how her children would handle her being a mother in space.[13] She went on to set an American record for time spent in space.[14] During an 188-day stay in space, she sent daily emails to keep in touch with her family.[15]

The first French woman in space was Claudie Haigneré, in 1996. She is married to Jean-Pierre Haigneré (also an astronaut), and is a mother of three, with one from that marriage.[16]

Some more recent examples include astronaut and mother[17] Nicole Stott, who made history in 2009 when she sent live Twitter messages from the ISS. Karen Nyberg became the 50th woman in space in 2008, and she is has logged more than 340 hours on long-term missions in space.[17][18] Cady Coleman[17] spent Mother's day in orbit in 2011.[19][20]

Family relationships

Human mothers in space face a number of challenges related to managing family life and spaceflight.[17] By the 2010s, email and Internet phones were noted as being used for communication with families when separated.[17] One mother in space maintained a more tangible connection with her husband and son while in orbit, by talking with them over a phone and having a video conference once a week.[21] According to the New York Times, another space mother brought her son's toys into orbit.[20]

Losses

The topic of mothers in space gained prominence in 1986, when the Space Shuttle Challenger exploded less than 2 minutes after launch with the loss of all hands. One of the crew, Christa McAuliffe, was a wife and mother of two.[22][23][24][25][26] One way the disaster is linked to motherhood in space is that McAuliffe's mother had supported her dreams to be the first teacher in space,[27] and she noted that although her daughter had trained for any number of emergencies on the Shuttle, no one had anticipated a disaster of that scope.[28]

In the 2003 Space Shuttle Colombia disaster the crew was lost on re-entry including the female astronauts Kalpana Chawla (also the mission commander) and Laurel Clark[29] Laurel Clark was an astronaut mother who died in the Space Shuttle Columbia disaster, leaving behind her husband and son. Years later, her husband noted how his son helped him through the loss of his wife.[30]

Physical effects of space on women

Female astronauts are subject to the same general physical effects of space travel as men. These include physiological changes due to weightlessness such as loss of bone and muscle mass, health threats from cosmic rays, dangers due to vacuum and temperature, and psychological stress.

One particularly female biological event is menstruation (aka the "period") which does not seem to be affected by space travel, in that it continues to occur.[31] One issue that waste disposal facilities must handle human blood, or whatever else comes along with dealing with period such as blood soaked sanitary wipes.[32] Additional calculations must be made for spaceflight that take into account additional products needed for dealing with these events, as well as changes in mass due.[33] In the United States, female space travels organize details of personal hygiene with the flight surgeon for space flight.[34] On shorter spaceflight females may try to temporarily shut down their period using medication.[35] One short flights it is also possible to time the menstruation so it does not occur during the spaceflight.[36] Periods were one of the reasons NASA was slow to accept women in spaceflight;how human body let alone a woman's body was unknown it was theorized that woman could be bleed to death in micro gravity or cause other issues.[37] As the knowledge base about how the human body responds to space grew (see Skylab) it seemed plausible and the 1978 astronaut class including six woman.[38] One concern was based on the issue that in micro-gravity fluids tend to pool inside body, and it was not clear without gravity what would happen to fluids released by the body during the period.[39] A 1964 study identified that a woman's period could effect her performance.[40] NASA engineered special bags of make-up to support women in space.[41] The uterus, ovaries, and breasts are at danger like other organs from increased radiation exposure.[42] Breast cancer may be related to bacteria that live in ducts in the breast.[43] This was discovered in a study by JPL examining breast cancer, spaceflight, and nipple aspirate fluid.[44] See also List of microorganisms tested in outer space)

It is reported that bra's are still worn in microgravity in many situations, such as when exercising on a treadmill because, while free from gravity, their inertia still causes them move.[45] Another aspect to woman in space is the release of nipple aspirate fluid, which comes from the same ducts that produce breast milk but can occur even when not making a lot milk.[46]

In the United States, woman in space was was studied in 1964 in which woman went through the same tests Mercury astronauts.[47] (see Mercury Seven)

Women and their head hair has also been noted, for example in micro gravity loose hairs can float freely and hair management has also been reported on.[48]

Scientific study of pregnancy in space

Gestation

NASA has not permitted pregnant astronauts to fly in space,[53] and to public knowledge there have been no pregnant women in space.[54] However, various science experiments have dealt with some aspects of pregnancy.[54]

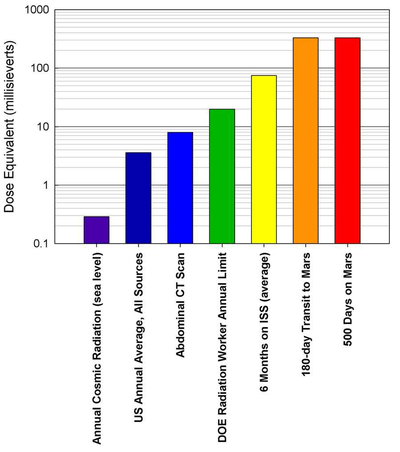

Exposure to radiation is a concern. For air travel, the United States' Federal Aviation Administration recommends a limit of 1 mSv total for a pregnancy, and no more than 0.5 mSv per month.[55] Astronauts on Apollo and Skylab missions received on average 1.2 mSv/day and 1.4 mSv/day respectively.[56] Exposures on the ISS average 0.4 mSv per day[56] (150 mSv per year), although frequent crew rotations minimize risk to individuals. A study published in 2005 in the International Journal of Impotence Research reported that short-duration missions (no longer than nine days) did not affect "the ability of astronauts to conceive and bear healthy children to term."[4] In another experiment, the frog Xenopus laevis successfully ovulated in space.[57]

Radiation shielding has been noted as an issue for space colonization because a woman's children could be sterile if she were exposed to too much ionizing radiation during the later stages of a pregnancy.[58] Ionizing radiation may destroy the egg cells of a female fetus inside a pregnant woman, rendering the offspring infertile even when grown.[58]

The lack of knowledge about pregnancy and birth control in microgravity has been noted in regards to conducting long-term space missions.[53]

While no human has gestated in space as of 2013, scientists have conducted experiments on non-human mammalian gestation.[59] Space missions that have studied "reproducing and growing mammals" includes Kosmos 1129 and 1154, as the Shuttle missions STS-66, 70, 72, and 90.[60] A Soviet experiment in 1983 showed that a rat who orbitted while pregnant later gave birth to healthy babies; the babies were "thinner and weaker than their Earth-based counterparts and lagged behind a bit in their mental development," although the developing pups eventually caught up.[54]

Childrearing

A 1998 Space Shuttle mission showed that rodent Rattus mothers were either not producing enough milk or not feeding children in space.[61] However, a later study on pregnant rats showed that the animals successfully gave birth and lactated normally.[54]

To date no human children have been born in space, nor have children gone into space.[54] Nevertheless, the idea of children in space is taken seriously enough that some have discussed how to write curriculum for children in space-colonizing families.[62]

Radiation

Like modern space-travel, air travel exposes people on aircraft to increased radiation from space as compared to sea level, including cosmic rays and from solar flare events.[55]

The United States FAA requires airlines to provide flight crew with information about cosmic radiation, and an International Commission on Radiological Protection recommendation for the general public is no more than 1 mSv per year.[55] In addition, many airlines do not allow pregnant flightcrew members, to comply with a European Directive.[55] The FAA has a recommended limit of 1 mSv total for a pregnancy, and no more than 0.5 mSv per month.[55] Information originally based on Fundamentals of Aerospace Medicine published in 2008.[55]

Massive particles are a concern for astronauts outside the earth's magnetic field who would receive solar particles from solar proton events (SPE) and galactic cosmic rays from cosmic sources. These high-energy charged nuclei are blocked by Earth's magnetic field but pose a major health concern for astronauts traveling to the moon and to any distant location beyond the earth orbit. Highly charged HZE ions in particular are known to be extremely damaging, although protons make up the vast majority of galactic cosmic rays. Evidence indicates past SPE radiation levels that would have been lethal for unprotected astronauts.[64]

A trip to Mars with current technology might be related measurments by the Mars Science Laboratory which for a 180-day journey estimated an exposure approximately 300 mSv, which would be equivalent of 24 CAT scans or "15 times an annual radiation limit for a worker in a nuclear power plant".[65] German standards for pregnant woman set a limit of 50 mSv/year for the gonads and uterus, and 150 mSv year for the breasts.[66] For pregnant woman, radiation increases the risk of childhood cancers for the fetus.[67]

Without effective shielding on spaceships, high-energy proton particles would probably sterilise any female foetus conceived in deep space and could have a profound effect on male fertility. "The present shielding capabilities would probably preclude having a pregnancy transited to Mars," said radiation biophysicist Tore Straume of Nasa's Ames Research Center in an essay for the Journal of Cosmology.— [58]

See also

- List of female astronauts

- List of space travelers by nationality

- Sex in space

- Maximum Absorbency Garment (NASA garment to help contain bodily emissions during spaceflight for men and women)

- Mercury 13

References

- ↑ "First Russian woman in International Space Station mission". BBC News. 26 September 2014. Retrieved 6 October 2014.

- ↑ Foust, Jeff (November 19, 2007). "AstroMom and Basstronaut, revisited". The Space Review.

- ↑

- 1 2 3 4 5 Brenhouse, Hillary (March 25, 2010). "China: Female Astronauts Must Be Married with Children". TIME.

- ↑ "Exclusive interview: Astronauts selection process". CCTV News. CNTV. June 16, 2012. Retrieved June 17, 2012.

- ↑ 孙兰兰 贾磊 (2012-06-13). "女航天员刘洋婆婆:希望媳妇能尽快生个孩子_资讯频道_凤凰网" [Mother-in-law of female astronaut Liu Yang: I hope daughter-in-law gives birth to a child as soon as possible]. News.ifeng.com. Retrieved 2012-06-18.

- ↑ Amos, Jonathan (June 16, 2012). "China launches space mission with first woman astronaut". BBC. Retrieved June 16, 2012.

- ↑ "Biography". Sault Ste. Marie Public Library. Retrieved 2011-04-17.

- ↑ "Inventive Women Biographies: Julie Payette".

- ↑ "Leaders Among Women in Space". Space Today Online. 2003. Retrieved 2010-02-08.

- ↑ Finneran, Michael (2012-09-19). "First Mother in Space, Mars Team to Be at NASA Langley Open House" (Press release). NASA.

- ↑ Abel, Allen. "The Family He Left Behind - Fifty years ago, Yuri Gagarin left earth. When he came back, everything changed.". http://www.airspacemag.com. Retrieved 19 May 2014. External link in

|work=(help) - 1 2 Foster, Amy E. Integrating Women Into the Astronaut Corps: Politics and Logistics at NASA, 1972-2004. Baltimore, Maryland: The Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 146. ISBN 978-1-4214-0195-9.

- ↑ Mihelich, Peggy (April 10, 2007). "Legendary astronaut still finds herself star-struck". CNN.

- ↑ Moore, Jo Ellen (2005), "Shannon Lucid - Astronaut", Spanish/English Read & Understand, Grade 3 (EMC 5309), Monterey, California: Evan-Moor Educational Publishers, p. 142

- ↑ Pearlman, Robert Z. (April 8, 2008). "For New Station Commander, Spaceflight is All in the Family". Space.com. Retrieved 2010-02-08.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Astronaut Mom Karen Nyberg Prepares for Mission and Motherhood 255 Miles Up". International Space Station. NASA. May 9, 2013.

- ↑ "Biographical Data: Karen L. Nyberg (Ph.D.), NASA Astronaut". Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center. November 2013.

- ↑ Moskowitz, Clara (May 6, 2011). "Mother's Day in Space: Astronaut Mom Connects With Son From Orbit". Space.com.

- 1 2 Kramer, A. (July 2, 2013). "Parenting From Earth's Orbit". The New York Times.

- ↑ Bolokhova, Elina (May 10, 2013). "NASA's Astronaut Mom Opens Up Before Six-Month Stint in Space". Parenting.

- ↑ Lathers, Marie (2010). Space Oddities: Women and Outer Space in Popular Film and Culture, 1960-2000. The Continuum International Publishing Group. p. 106. ISBN 978-1-4411-9049-9.

- ↑ Corrigan 2000, p. 123

- ↑ "The Crew of the Challenger Shuttle Mission in 1986". NASA. 2004-10-22. Retrieved 2009-01-09.

- ↑ Corrigan 2000, p. 40

- ↑ Burgess, Colin; Corrigan, Grace George (2000). Teacher in space: Christa McAuliffe and the Challenger legacy. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0-8032-6182-9.

- ↑ Corrigan, Grace George (2000). A Journal for Christa: Christa McAuliffe, Teacher in Space. Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0-8032-6411-9.

- ↑ Cook, D. (2005). Mothers of Influence – Inspiring Stories of Women Who Made a Difference in Their Children and Their World. Honor Books. p. 71. ISBN 1-56292-368-4.

- ↑ [https://airandspace.si.edu/stories/editorial/reflections-loss-sts-107-space-shuttle-columbia-ten-years-ago

- ↑ Dunn, Marcia (January 30, 2013). "Father and son remembers [sic] astronaut mom". Cape Canaveral, Florida: MSN News.

- ↑ [http://www.cnn.com/2016/05/11/health/space-gynecology-periods-in-microgravity/

- ↑ [http://www.cnn.com/2016/05/11/health/space-gynecology-periods-in-microgravity/

- ↑ [http://www.cnn.com/2016/05/11/health/space-gynecology-periods-in-microgravity/

- ↑ [http://www.cnn.com/2016/05/11/health/space-gynecology-periods-in-microgravity/

- ↑ [http://www.cnn.com/2016/05/11/health/space-gynecology-periods-in-microgravity/

- ↑ [http://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2016/04/menstruating-in-space/479229/

- ↑

- ↑ http://www.popsci.com/brief-history-menstruating-in-space

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑ http://www.salon.com/2013/07/02/female_astronauts_wear_bras_says_an_astronaut/ ]

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑ Kerr, Richard (31 May 2013). "Radiation Will Make Astronauts' Trip to Mars Even Riskier". Science. 340 (6136): 1031. doi:10.1126/science.340.6136.1031. Retrieved 31 May 2013.

- ↑ Zeitlin, C.; et al. (31 May 2013). "Measurements of Energetic Particle Radiation in Transit to Mars on the Mars Science Laboratory". Science. 340 (6136): 1080–1084. doi:10.1126/science.1235989. Retrieved 31 May 2013.

- ↑ Chang, Kenneth (30 May 2013). "Data Point to Radiation Risk for Travelers to Mars". New York Times. Retrieved 31 May 2013.

- ↑ Gelling, Cristy (June 29, 2013). "Mars trip would deliver big radiation dose; Curiosity instrument confirms expectation of major exposures". Science News. 183 (13): 8. Retrieved July 8, 2013.

- 1 2 Foster, p. 139.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Stierwalt, Sabrina (May 2006). "Can a human give birth in space?". Ask an Astronomer. Cornell University.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Davis, Jeffrey R.; Johnson, Robert; Stepanek, Jan; Fogarty, Jennifer A., eds. (2008). Fundamentals of Aerospace Medicine (Fourth ed.). pp. 221–230. Retrieved 2010. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - 1 2 Cucinotta, Francis A., "Table-4. Average dose (D) or dose-rate recorded by dosimetry badge and estimates of the effective doses, E received by crews in NASA programs through 2004", Space Radiation Organ Doses for Astronauts on Past and Future Missions (PDF), p. 22, retrieved 1 February 2014

- ↑ Ronca, p. 218.

- 1 2 3 Taylor, Jerome (February 14, 2011). "Why infertility will stop humans colonising space". The Independent.

- ↑ Ronca, April E., "Mammalian Development in Space", in Cogoli, Augusto, Advances in Space Biology and Medicine, 9, Elsevier Science B.V., p. 219, ISBN 0-444-51353-1

- ↑ Ronca, p. 222.

- ↑ "Nasa To Probe The Deaths Of 51 Baby Rats In Space". Chicago Tribune. April 29, 1998.

- ↑ Britton, Alan, "A school curriculum for the children of stace settlers", in Landfester, Ulrike; Remuss, Nina-Louisa; Schrogl, Kai-Uwe; Worms, Jean-Claude, Humans in Outer Space: Interdisciplinary Perspectives, p. 65

- ↑ O'Neill, Gerard K. The High Frontier: Human Colonies in Space, third edition. Apogee Books, 2000.

- ↑ "Superflares could kill unprotected astronauts". New Scientist. 21 March 2005.

- ↑ http://www.space.com/24731-mars-radiation-curiosity-rover.html

- ↑

- ↑

External links

- Women in Space from Telegraph Jobs

- 50 years of humans in space: European Women in Space (ESA)