William Yolland

William Yolland CB, FRS (17 March 1810 – 5 September 1885) was an English military surveyor, astronomer and engineer, and was Britain’s Chief Inspector of Railways from 1877 until his death. He was a redoubtable campaigner for railway safety, often in the face of strong opposition, at a time when railway investment was being directed towards the expansion of the networks rather than the prevention of accidents. He was a member of the three-man committee of inquiry into the Tay Bridge disaster.[1]

Career

Yolland was born in Plympton St Mary, Devon, the son of the land agent to Lord Morley, Plymouth, and his father promoted the boy’s interest in surveying and land management by enrolling him at a school specialising in mathematics.[1] He was commissioned into the Royal Engineers in 1828 and completed his technical training at the Royal School of Military Engineering in Chatham, Kent, in 1831.

After service in Britain, Ireland and Canada he was posted to the Ordnance Survey in 1838. He made such a strong impression there, particularly with his mathematical knowledge and publications on astronomy,[2] that in 1846 he was nominated to head the organisation by its departing Superintendent, General Thomas Colby.[3] He was, however, thought too young for the post and an older officer (who had no survey experience) was appointed instead. This new Superintendent, Colonel Lewis Hall, despatched Yolland to Ireland to avoid his embarrassment in commanding a more qualified officer, but the survey there was of greater importance than Hall had realised: Parliament had noticed that revenue was being lost as land assessments for tax were not up to date and Yolland’s progress there was followed with interest. In 1849 he was called to appear before a parliamentary select committee to explain how his method of mapping settlements in Ireland could be applied in England, as more detailed town maps were urgently needed to assist in the planned reforms of town sanitation. The interest in Yolland’s work in Ireland survives to this day: as a young man he appears as a leading character in Translations, a modern play set in nineteenth century Co. Donegal.[4] The account of Yolland in Brian Friel's play is fictionalized, however, as he is called George Yolland and is missing, possibly dead, at the play's end. General Colby appears as "Captain Lancey".[4]

On his return to England he was placed in charge of the Ordnance Survey’s new offices in Southampton, where amongst other things he produced a set of maps of the City itself which were recently reproduced by the City Council for purchase by the public. When Colonel Hall retired in 1854 it was expected that, at the second opportunity, Yolland would be offered the Superintendent’s post. However Hall, who had continued to resent his subordinate’s abilities, succeeded in blocking the appointment.[3] Yolland left the Ordnance Survey immediately afterwards.

The Railway Inspectorate of the Board of Trade was invariably staffed from the Royal Engineers and Yolland, although still an army officer (by then a major) had no difficulty in securing a post with that organisation. Additionally, he was appointed to a commission to report on the best methods of scientific and technical training for military officers. His findings were accepted and his report was still influencing the training of military engineers (in Britain and the United States) at the end of the twentieth century.[5]

Yolland retired from the army in 1863, with the rank of lieutenant-colonel, although he retained his position with the Railway Inspectorate. At a time when Britain’s railway mileage was expanding at a great rate, his duties included the inspection of new lines and he took full opportunity to insist that the latest safety features, such as signal interlocking and block working, should be deployed.[6] His campaign for continuous automatic brakes was initially less successful.[7] At that time the Inspectorate had no statutory powers with regard to existing lines; all too frequently Yolland found himself reporting, in his characteristic rigorous manner, the organisational failures and neglect that had led to serious accidents.

In 1877 he was appointed HM Chief Railway Inspector in succession to Henry Whatley Tyler. He died in 1885 in Atherstone, Warwickshire.

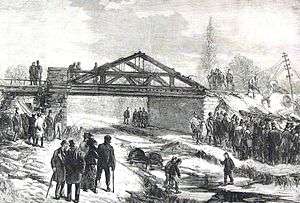

Shipton-on-Cherwell accident (1874)

One of the worst railway crashes he investigated occurred on the Great Western Railway near Oxford.[8] The accident occurred on 24 December 1874 at Shipton-on-Cherwell, just north of Kidlington when a passenger train was derailed and crashed down the embankment. The investigation led by Yolland established the root causes very quickly, and further details emerged at the public enquiry set up by the Board of Trade. By tracing the marks on the sleepers behind the derailed train, Yolland established that the small 4 wheel carriage behind the locomotive had suffered a broken wheel, which disintegrated and caused the derailment. The driver braked hard and the carriages behind cannonaded into the 4 wheeler, crushing it entirely, as well as themselves running off the track. The accident occurred near to a small bridge crossing the Oxford canal and 34 passengers died from their injuries.

1852 map of York

Yolland worked with Captain Tucker; R.E. on the 1852 "Plan of York".[9]

Tay bridge disaster (1879)

He was a member of the Board of Inquiry into the Tay Bridge disaster, with fellow members Henry Cadogan Rothery and William Henry Barlow. A train was lost on the night of 28 December 1879 while crossing the Tay estuary just south of Dundee. The centre section of the 2-mile-long bridge collapsed during a storm, with the loss of all on board the train. The inquiry sat initially in Dundee to hear eye witness accounts of the accident, and then in London for expert evidence. They produced their final report in June 1880, and concluded that the bridge was "badly designed, badly built and badly maintained". Yolland went on to report on the state of other Bouch bridges, especially a very similar structure at Montrose, the South Esk Viaduct. The bridge was in a dire state according to Yolland in his Railway Inspectorate report, and had eventually to be demolished and replaced by a safer structure.[10][11]

Honours and awards

- Fellow of the Royal Astronomical Society 1840

- Fellow of the Royal Society 1859

- Fellow of the Royal Society of Arts 1860

- Companion of the Order of the Bath 1881

Notes

- 1 2 Vetch (2004)

- ↑ "Obituary". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. London: Royal Astronomical Society. 46: 201. 1886. Bibcode:1886MNRAS..46..201.. doi:10.1093/mnras/46.4.201.

- 1 2 Owen, Tim; Pilbeam, Elaine (1992). Ordnance Survey: Map makers to Britain since 1791. Southampton, England: Ordnance Survey. pp. 44–46. ISBN 0-319-00498-8.

- 1 2 Bullock, Kurt (2000). "Possessing Wor(l)ds: Brian Friel's Translations and the Ordnance Survey". New Hibernia Review. St Pauls, MN. 4 (2). ISSN 1092-3977.

- ↑ Preston, Richard A (1980). "Perspectives in the History of Military Education and Professionalism". US Air Force Harmon Memorial Lecture. Retrieved 9 January 2007.

- ↑ Gordon, William John (1910). "Interlocking Signals". Our Home Railways. 1. London: Frederick Warne and Co. p. 198.

- ↑ Nock, O.S. (1955). The Railway Engineers. London: B.T.Batsford Ltd. p. 239.

- ↑ Yolland, William (April 1875). "Shipton-on-Cherwell Railway Accident, 24th December 1874" (PDF). Eyre & Spottiswoode.

- ↑ Plan of York, 1852 (Sheets 1 - 21): Surveyed in 1850, by Captain Tucker; R.E. Engraved in 1851, under the direction of Captain Yolland, R.E. at the Ordnance Map Office, Southampton, and Published by Lt. Colonel Hall R.E. Superintendent, 1st. Sept., 1852.

- ↑ "Site Record for Montrose, South Esk Viaduct". Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland. Retrieved 19 January 2012.

- ↑ The Building news and engineering journal. London. 39: 781. December 1880. Missing or empty

|title=(help)

References

- Simmons, Jack and Biddle, Gordon (1997): The Oxford Companion to British Railway History. Oxford University Press.

- Vetch, R. H., revised Matthew, C. G. (2004): Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. The first edition of this text is available as an article on Wikisource:

"Yolland, William". Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900.

"Yolland, William". Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900. - Peter R. Lewis, Beautiful Railway Bridge of the Silvery Tay: Reinvestigating the Tay Bridge Disaster of 1879, Tempus, 2004, ISBN 0-7524-3160-9.

- Peter R Lewis and Alistair Nisbet, "Wheels to Disaster!: The Oxford train wreck of Christmas Eve, 1874", Tempus (2008) ISBN 978-0-7524-4512-0