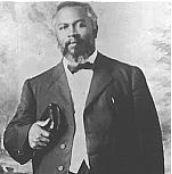

William J. Seymour

| William Joseph Seymour | |

|---|---|

|

Leader of the Azusa Street Revival | |

| Born |

May 2, 1870 Centerville, Louisiana, United States |

| Died |

September 28, 1922 (aged 52) Los Angeles, California, United States |

| Occupation | Evangelist |

| Spouse(s) | Jenny Evans Moore, 1906–1922, (his death) |

William Joseph Seymour (May 2, 1870 – September 28, 1922) was an American minister, and an initiator of the Azusa Street Revival.[1] Seymour was one of the most influential individuals in the revival movement that grew into the Pentecostal and Charismatic movements, along with other figures such as Charles Parham, Howard A. Goss, and Frank Bartleman.[2] Seymour's emphasis on racial equality drew many historically disenfranchised people to the movement, and due to his influence the revival grew very quickly.[3]

Early life and career

Seymour was born to former slaves Simon and Phyllis Salabar Seymour in Centerville, Louisiana.[4] He was baptized at the Roman Catholic Church of the Assumption in Franklin, and attended the New Providence Baptist Church in Centerville with his family.[5] The racial violence in the American South at this time — Louisiana had one of the highest rates of lynchings in the nation — would have a huge effect on Seymour's later emphasis on racial equality at the Azusa mission.[6]

In the 1890s, Seymour left the South in order to travel north, to places such as Memphis, St. Louis, and Indianapolis.[7] By doing this, he escaped the horrific violence aimed at African Americans in the south during this period. Though he would continue to face racial prejudice in the north, it was not at the violent level that he faced in the South.[8] In 1895, Seymour moved to Indianapolis, where he attended the Simpson Chapel Methodist Episcopal Church.[9] It was at this church where Seymour became a born-again Christian.[10]

During Seymour's travels, he was influenced by Daniel S. Warner's Evening Light Saints, a Holiness group dedicated to racial equality.[11] Their view of a racially egalitarian church would influence his theology for the rest of his life.[11] In 1901, Seymour moved to Cincinnati, where his views on holiness and racial integration were shaped by a Bible school he attended.[10] During this time, he contracted smallpox and subsequently went blind in his left eye. After overcoming the smallpox Seymour was ordained by the Evening Light Saints.[12] Seymour then traveled to Jackson, Mississippi, where he visited Charles Price Jones, and left the South with a very firm commitment to his beliefs.[13]

In 1906, due to the encouragement of his friend Lucy F. Farrow, Seymour joined a newly formed Bible school founded by Charles Parham in Houston, Texas.[14] Parham's teachings on the baptism of the Holy Spirit stuck with Seymour and influenced his later doctrine and theology. Seymour did not agree, however, with some of Parham's more radical views.[15] He developed a belief in glossolalia ("speaking in tongues") as a confirmation of the gifts of the Holy Spirit when he witnessed it from one of his followers. He believed this proved that the person was born-again and could then go to Heaven. Seymour did not remain at the school for very long — he spent just six weeks there, and left before his studies were complete.[16] In late January or early February 1906, Neely Terry asked Seymour to pastor a church in Los Angeles.[17] Feeling called by God, Seymour took the opportunity against Parham's wishes, and moved to Los Angeles.[17]

Azusa Street Revival

Seymour arrived in Los Angeles on February 22, 1906, and began preaching at Julia Hutchins's Holiness Church two days later.[18] Less than two weeks later, he was expelled from the mission by Hutchins, who had padlocked the church door shut due to outrage over Seymour's claims on tongue-speech.[18] Without a place to go, Seymour began staying at Edward Lee's home, and before long a prayer group began meeting at their house.[19] The group quickly grew too large, and it was moved to Richard Asberry's house. On April 9, 1906, Lee spoke in tongues after Seymour laid hands on him, and the Azusa Street Revival began.[20] Seymour himself received the Holy Spirit baptism three days later, on April 12.[3] Soon the group grew too large for the Asberry's house as well, and the weight of the attendees caused the front porch to collapse, forcing Seymour to look for a new location.[21] The mission moved to an old African Methodist Episcopal church building on Azusa Street, thus giving the movement its name.[19]

At the beginning, the movement was racially egalitarian. Blacks and whites worshiped together at the same altar, against the normal segregation of the day.[22] In September 1906, the leaders of the revival began printing the Apostolic Faith newsletter, and argued through it that the Spirit was bringing people together across all social lines and boundaries to the revival.[3] Seymour not only rejected the existing racial barriers in favor of "unity in Christ", he also rejected the then almost-universal barriers to women in any form of church leadership. Latinos soon began attending as well, after a Mexican-American worker received the Spirit baptism on April 13, 1906.[23]

From his base on Azusa Street he began to preach his doctrinal beliefs. This revival meeting extended from 1906 until 1909, and became known as the Azusa Street Revival. It became the subject of intense investigation by mainstream Protestants. Some left feeling that Seymour's views were heresy, while others accepted his teachings and returned to their own congregations to expound them. The resulting movement became widely known as "Pentecostalism", likening it to the manifestations of the Holy Spirit recorded as occurring in the first two chapters of Acts as occurring from the day of the Feast of Pentecost onwards.[24]Charles Harrison Mason, founder of the Church of God in Christ, received the baptism of the Holy Spirit at the revival.[25]

In October 1906, Parham arrived at the Azusa revival. After preaching several times, he became disgusted at the state of the revival.[26] After observing some ecstatic practices and racial mixing in worship, he went to the pulpit and began to preach that God was disgusted at the state of the revival.[27] Seymour refused to back down from the doctrines of the revival, and Parham denounced the Azusa revival as false.[28] He was subsequently removed from the revival by Glenn Cook, one of the Seymour's trustees.[28] Parham began to attack Seymour and Azusa as being from the devil shortly after. He claimed that Seymour had corrupted the teaching of tongue-speech — Parham believed that the spoken tongues had to be a recognizable human language (xenoglossy), while Seymour's theology allowed for a divine language that could not be understood by human ears (glossolalia).[29] Parham denounced these views as unscriptural.[29] Parham denounced the racial mixing of the revival, causing the egalitarian Seymour to disassociate with him.[29]

Later life

As the revival went on, issues began to pop up that would affect Seymour's leadership. It took only a couple of years before race issues within the movement started to become divisive. Seymour often chose white pastors instead of black pastors in charge whenever he left Los Angeles, causing black members to fear the mission was in danger of being taken over.[30] Unfounded accusations by some members about embezzlement weighed heavily on Seymour, and affected his influence in the mission.[31] Other missions affiliated with Azusa began to open, and drew people away from the main revival.[32] Racial segregation quickly became an issue in the movement, and the problem only grew as time went on.

On May 13, 1908, Seymour married Jennie Moore Evans.[32] This came as a shock to some in the church, who saw it as a violation of sanctification and as going against the mission's message of the end-times. After the wedding, Seymour's coeditor of the Apostolic Faith newsletter, Clara Lum, left Azusa very suddenly with the newsletter and the mailing lists in hand, and moved to Portland.[33] She refused to give control of the paper back to Seymour when he came to see her, and with no recourse left to him, he could no longer spread his ideas easily.[34] The loss of the newsletter was a crippling blow to the Azusa revival.

The biggest blow to Seymour's authority in the later movement, however, was the split between Seymour and William Durham. During one of Seymour's revival tours in 1911, he asked Durham if he would serve as the visiting preacher; he agreed, but his more extreme views on sanctification caused a schism in the budding Pentecostal church.[35] Seymour was asked to return to Azusa immediately, while his wife Jennie padlocked Durham out of the mission.[36] Durham began to attack Seymour publicly, launching an extreme polemic by claiming that Seymour was no longer following the will of God and was not fit to be a leader, devastating Seymour.[37] Even after Durham's sudden death in 1912, the Pentecostal community in Los Angeles remained split.[38]

On September 28, 1922, Seymour suffered two heart attacks, and died in his wife Jennie's arms.[39] He was buried in Evergreen Cemetery in East Los Angeles, near influential Pentecostal preacher Francisco Olazábal.[40] Jennie Seymour died on July 2, 1936, and was buried next to him.[41]

Legacy

The spirit of revival spread from Azusa all over the United States, and many missions modeled themselves after Azusa, especially the racially integrated services.[42] By 1914, Pentecostalism had spread to almost every major U.S. city.[42] The egalitarian message was very attractive to many people experiencing some sort of racial division all over the world.[43] The mission quickly spread all around the world: from Liberia, to the Middle East, to Sweden and Norway, the Pentecostal message flourished rapidly and many of the missionaries spreading the new message had themselves been at the Azusa revival.[44] Seymour's global influence spread far beyond his direct interactions with the missions.

Protestant Pentecostals trace their roots back to early leaders such as Seymour, and estimates of worldwide Pentecostal membership ranges from 115 million to 400 million.[2] Most modern Charismatic groups can claim some lineage to the Azusa Street Revival and Seymour.[2] Pentecostalism is the second largest Christian denomination in Latin America, behind Roman Catholicism, and many African churches are Pentecostal or Charismatic in practice.[45] While there were many other centers for revivals, such as Topeka, India, and Chicago, it was the socially transgressive and egalitarian message of Azusa that appealed to many converts.[46][47] Many specific doctrines taught at Azusa, such as glossolalia, are still taught today, as opposed to Parham's xenoglossy.[48] While the movement largely fractured along racial lines within a decade, the splits were in some ways less deep than the vast divide that seems often to separate many white religious denominations from their black counterparts.

References

- ↑ Corcoran, Michael. "How a humble preacher ignited the Pentecostal fire". Austin news. Retrieved November 19, 2011.

- 1 2 3 Borlase, 235.

- 1 2 3 Espinosa, 56.

- ↑ Borlase, Craig. William Seymour: A Biography. Lake Mary, FL: Charisma House, 2006. Print.

- ↑ Espinosa. WIlliam J. Seymour and the Origins of Global Pentecostalism: A Biography and Documentary History. p. 47.

- ↑ Bartleman, Azusa Street, 47, 54.

- ↑ Espinosa, 48.

- ↑ Synan, Vinson; Fox, Charles R. (2012). William J. Seymour: Pioneer of the Azusa Street Revival. Alachua, FL: Bridge Logos Foundation. p. 25.

- ↑ Espinosa, 49.

- 1 2 Lake, "Origins of the Apostolic Faith Movement," 3.

- 1 2 Synan, 47.

- ↑ Espinosa, Gaston. William J. Seymour and the Origins of Global Pentecostalism: A Biography and Documentary History. Print.

- ↑ Lake, "Origins of the Apostolic Faith Movement," 3; Irwin, "Charles Price Jones," 45.

- ↑ Espinosa, 50.

- ↑ Synan, 354.

- ↑ Robeck, Cecil M. The Azusa Street Mission and Revival: The Birth of the Global Pentecostal Movement. Nashville: Nelson Reference & Electronic, 2006. p. 4.

- 1 2 Espinosa, 51.

- 1 2 Espinosa, 53.

- 1 2 Robeck, 5.

- ↑ Espinosa, 55.

- ↑ Espinosa, 57.

- ↑ AF (December 1906): I; AF, "The Same Old Way," 3; AF, Bible Pentecost," I; Bartleman, Azusa Street, 47, 54.

- ↑ Espinosa, 59.

- ↑ Acts 2:1-4

- ↑ McGee, Gary. "William J. Seymour and the Azusa Street Revival". The Enrichment Journal. Retrieved November 19, 2011.

- ↑ Espinosa, 96.

- ↑ Espinosa, 96-97.

- 1 2 Espinosa, 97.

- 1 2 3 Espinosa, 99.

- ↑ Espinosa, 112.

- ↑ Espinosa, 112-13.

- 1 2 Espinosa, 113.

- ↑ Espinosa, 114.

- ↑ Robeck, 305.

- ↑ Robeck, 316.

- ↑ Blumhofer, "William H. Durham," in Goff and Wacker, Portraits of a Generation, 138-39.

- ↑ Espinosa, 122-23

- ↑ Espinosa, 123.

- ↑ Espinosa, 145.

- ↑ Espinosa, Gaston (1999). ""El Azteca": Francisco Olazabal and Latino Pentecostal Charisma, Power, and Faith Healing in the Borderlands". Journal of the American Academy of Religion.

- ↑ Espinosa, 148.

- 1 2 Espinosa, 70.

- ↑ AF, "Tongues as a Sign," 2.

- ↑ Robeck, 268.

- ↑ Robeck, 14.

- ↑ Creech, Joe. "Visions of Glory: The Place of the Azusa Street Revival in Pentecostal History." Church History 65.03 (1996): 408.

- ↑ Espinosa, 14.

- ↑ Espinosa, 151.