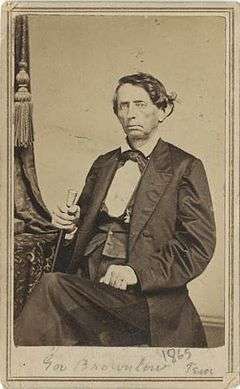

William Gannaway Brownlow

| William Gannaway Brownlow | |

|---|---|

| |

| 17th Governor of Tennessee | |

|

In office April 5, 1865 – February 25, 1869 | |

| Preceded by |

Andrew Johnson as Military Governor |

| Succeeded by | Dewitt Clinton Senter |

| United States Senator from Tennessee | |

|

In office March 4, 1869 – March 3, 1875 | |

| Preceded by | David T. Patterson |

| Succeeded by | Andrew Johnson |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

August 29, 1805 Wythe County, Virginia |

| Died |

April 29, 1877 (aged 71) Knoxville, Tennessee |

| Resting place |

Old Gray Cemetery Knoxville, Tennessee |

| Political party | Whig, American, Republican |

| Spouse(s) | Eliza O'Brien (1836) |

| Relations | Walter P. Brownlow (nephew) |

| Children | Susan, John Bell, James, Mary, Fannie, Annie, Caledonia Temple |

| Profession | Minister, newspaper editor |

| Religion | Methodist |

| Signature |

|

William Gannaway "Parson" Brownlow (August 29, 1805 – April 29, 1877) was an American newspaper editor, minister, and politician. He served as Governor of Tennessee from 1865 to 1869 and as a United States Senator from Tennessee from 1869 to 1875. Brownlow rose to prominence in the 1840s as editor of the Whig, a polemical newspaper in East Tennessee that promoted Whig Party ideals and opposed secession in the years leading up to the American Civil War. Brownlow's uncompromising and radical viewpoints made him one of the most divisive figures in Tennessee political history and one of the most controversial Reconstruction Era politicians of the United States.

Beginning his career as a Methodist circuit rider in the 1820s, Brownlow was both censured and praised by his superiors for his vicious verbal debates with rival missionaries of other sectarian Christian beliefs. And later as a newspaper publisher and editor, he was notorious for his relentless personal attacks against his religious and political opponents, sometimes to the point of being physically assaulted. At the same time, Brownlow was successfully building a large base of fiercely loyal subscribers.[1]

Brownlow returned to Tennessee in 1863 and in 1865 became the war governor with the U.S. Army behind him. He joined the Radical Republicans and spent much of his term opposing the policies of his longtime political foe Andrew Johnson.[1] His gubernatorial policies, which were both autocratic and progressive, helped Tennessee become the first former Confederate state to be readmitted to the Union in 1866.[1] Brownlow's policy of disenfranchising both ex-Confederate leaders and soldiers while utilizing state government to enfranchise African-American former slaves with the right to vote in Tennessee elections fueled the rise of the Ku Klux Klan in the late 1860s.[1]

Early life

Brownlow was born in Wythe County, Virginia, in 1805, the eldest son of Joseph Brownlow and Catherine Gannaway. Joseph Brownlow, an itinerant farmer, died in 1816, and Catherine Gannaway followed three months later, leaving William orphaned at the age of 10. Brownlow and his four siblings were split up among relatives, with Brownlow spending the remainder of his childhood on his uncle John Gannaway's farm. At age 18, Brownlow went to Abingdon where he learned the trade of carpentry from another uncle, George Winniford.[2]:1–3

In 1825, Brownlow attended a camp meeting near Sulphur Springs, Virginia, where he experienced a dramatic spiritual rebirth. He later recalled that, suddenly, "all my anxieties were at an end, all my hopes were realized, my happiness was complete."[2]:4 He immediately abandoned the carpentry trade and began studying to become a Methodist minister. In Fall 1826, he attended the annual meeting of the Holston Conference of the Methodist Church in Abingdon. He applied to join the travelling ministry (commonly called "circuit riders"), and was admitted that year by Bishop Joshua Soule.[2]:6

In 1826, Soule gave Brownlow his first assignment— the Black Mountain circuit in North Carolina. It was here that Brownlow first ran afoul of the Baptists— who were spreading quickly throughout the Southern Appalachian region— and developed an immediate dislike of them, considering them narrow-minded bigots who engaged in "dirty" rituals such as foot washing.[2]:18 The following year, Brownlow was assigned to the circuit in Maryville, Tennessee, where there was a strong Presbyterian presence, and later recalled being constantly harassed by a young Presbyterian missionary who taunted him with Calvinistic criticisms of Methodism.[2]:19

The competition in Southern Appalachia for converts and their tithes among the Baptists, Methodists, and Presbyterians was fierce, and diatribes against rival religions were commonplace among missionaries. Brownlow, however, took such debates to a whole new level, attacking not only Baptist and Presbyterian theology, but also the character of his rival missionaries. In 1828, he was sued for slander, but the suit was dismissed. In 1831, he was sued for libel by a Baptist preacher, and ordered to pay his accuser $5.[2]:22 In 1832, Brownlow was assigned to the Pickens District in South Carolina, which he claimed was "overrun with Baptists" and "nullifiers." Unable to make headway in the district, he circulated a venomous 70-page pamphlet blasting the district's Baptists, and galloped safely back into the mountains as the district's enraged residents demanded he be hanged.[2]:25 Brownlow's run-in with the nullifiers would later influence his views on secession.

In 1836, Brownlow married Eliza O'Brien, and the two settled down in her hometown of Elizabethton, Tennessee, where he took a job as a clerk at her family's iron foundry.[3] Although Brownlow left the circuit shortly thereafter, he continued his staunch defense of Methodism in later newspaper columns and books, and for the remainder of his life he was known to friend and foe alike as "Parson Brownlow."[2]

Early newspaper owner

Historian Stephen Ash says:

- What made the Parson stand out was, more than anything else, his vitriolic tongue and pen. Over the course of his long career he took up many causes. These included not only Methodism, Whiggery, and the Union, but also temperance, Know-Nothingism, and slavery. His favorite method of promoting those causes was to chastise and ridicule his opponents, and few men could do so with as much venomous wit as he. Baptists, Presbyterians, Catholics, Mormons, Democrats, Republicans, secessionists, drunks, immigrants, and abolitionists-all were at one time or another on the receiving end of Brownlow's merciless broadsides. Not surprisingly, he made many enemies. A number of them replied in kind; some tried to kill him.[4]

Brownlow gave up circuit riding and quickly settled with the family of his newly wed wife in Elizabethton during 1839, where the rising local attorney T.A.R. Nelson suggested that Brownlow should launch a newspaper to support Whig Party candidates in the upcoming elections. Brownlow partnered in Elizabethton with newspaper publisher, and former Emmerson associate, Mason R. Lyon, and the two launched the Tennessee Whig during May 1839.[5]

As Brownlow's vituperative editorial style quickly brought bitter division to Elizabethton, and he began quarreling with local Whig-turned-Democrat Landon Carter Haynes. In the mid-1830s, Brownlow wrote several anti-nullification articles for Judge Thomas Emmerson's Jonesborough, Tennessee-based paper, the Washington Republican and Farmer's Journal (Emmerson had earlier encouraged Brownlow to pursue a career in journalism). After the Whig relocated from Elizabethton and to Jonesborough in May 1840, Brownlow accosted Haynes in the street and began beating him with a sword cane, prompting Haynes to draw a pistol and shoot him in the thigh.[2]:39 Haynes was hired as editor of the Democratic Tennessee Sentinel the following year, and the two blasted each other in their respective papers for the next several years.[5]

In 1845, Brownlow ran against Andrew Johnson for the state's 1st District seat in the U.S. House of Representatives. Using the Whig to support his campaign, he accused Johnson of being illegitimate, suggested Johnson's relatives were murderers and thieves, and stated that Johnson was an atheist.[2]:121 Johnson won the election by 1,300 votes, out of just over 10,000 votes cast.[2]:117

Brownlow supported Whig policies such as a national bank, federal funding for internal improvements (more specifically, public improvements to the Moccasin Bend area of the Tennessee River near Chattanooga allowing for better steamboat transportation of goods to New Orleans), developing industries within northeast Tennessee, and a weakened presidency.[2]:111 He called Andrew Jackson the "greatest curse that ever yet befell this nation,"[6] and attacked Jackson's supporters, the Locofocos, in his 1844 book, A Political Register.[2]:113 While Brownlow steadfastly supported Whig candidates such as John Bell and James C. Jones, his true political idol was Kentucky senator Henry Clay. Clay was consistently Brownlow's first choice for the party's presidential candidate throughout the 1840s.[2]:112 Brownlow's son, John, recalled that one of the few times he ever saw his father cry was after he had received the news of Clay's defeat in the 1844 presidential election.[2]:116

In May 1849, Brownlow relocated the Whig to Knoxville, Tennessee, where he was already well known for his clashes with the Democratic Standard, which he had dubbed a "filthy lying sheet."[6] Prior to his departure, an unknown assailant clubbed Brownlow in the head, leaving him bedridden for two weeks. He blamed this act on Knoxville's newspaper interests, who feared his competition.[2]:37–44 Upon his arrival, he became embroiled in an editorial war with Knoxville Register editor John Miller McKee that lasted until McKee's departure in 1855.[7]

Brownlow joined the Sons of Temperance in 1850,[8] and promoted temperance policies in the Whig (one of his more common personal attacks was to accuse his opponents of being "drunkards"). Following the collapse of the Whig Party in the mid-1850s, he aligned himself with the Know Nothing movement, as he had long shared this movement's anti-Catholic and nativist sentiments.[2]:125 In 1856, he published a book, Americanism Contrasted with Foreignism, Romanism and Bogus Democracy, which attacked Catholicism, foreigners and Democratic politicians.

In the late 1850s, Brownlow turned his attention to Knoxville's Democratic Party leaders and their associates. He quarreled with the radical Southern Citizen, a pro-secession newspaper published by businessman William G. Swan and Irish Patriot John Mitchel (who spent time in Knoxville while in exile), and on at least one occasion, threatened Swan with a revolver.[2]:49 Following the failure of the Bank of East Tennessee in 1858, Brownlow ruthlessly assailed its directors. His attacks forced A.R. Crozier and William Churchwell to flee the state, and drove John H. Crozier from public life. Brownlow sued another director, J. G. M. Ramsey, winning a civil judgement on behalf of the bank's depositers.[9]:289–290

Partially a result of Brownlow's persistent opposition to secession within the pages of his newspapers (and partially due to his long-time feud with Confederate sympathizer, banker, and Tennessee historian J. G. M. Ramsey), he was later jailed by Confederate States military authorities (the CSA district attorney in Knoxville, Tennessee being related to J. G. M. Ramsey) in December 1861, pardoned, and subsequently forced into exile in the northern United States.

Sectarian debates

While Brownlow left the preaching circuit in the 1830s, he continued attacking critics of the Methodist faith until the Civil War. In 1843, his feud with Haynes led to Haynes being barred from the Methodist clergy.[10] That same year, J.M. Smith, editor of the Abingdon Virginian, accused Brownlow of having stolen jewelry at a camp meeting. Brownlow denied the charge, and accused Smith of being an adulterer. At a meeting of the Methodists' Holston Conference that year, Smith tried unsuccessfully to have Brownlow expelled from the church.[2]:42

In the late 1840s, Brownlow quarreled with Presbyterian minister Frederick Augustus Ross (1796–1883), who, from 1826 till 1852, was pastor of Old Kingsport Presbyterian Church in Kingsport, Tennessee, where Ross had taken up in 1818. Ross had earlier "declared war" on Methodism as a co-editor in his Calvinist Magazine, published from 1827 to 1832. Although distracted by internecine conflict within the Presbyterian church for nearly a decade, he relaunched the Calvinist Magazine in 1845. Ross argued that the Methodist Church was despotic, comparing it to a "great iron wheel" that would crush American liberty. He stated that most Methodists were descended from Revolutionary War loyalists, and accused the Methodist Church founder, John Wesley, of believing in ghosts and witches.[8]

Brownlow initially responded to Ross with a running column, "F.A. Ross' Corner," in the Jonesborough Whig. In 1847, he launched a separate paper, the Jonesborough Quarterly Review, which was dedicated to refuting Ross's attacks, and embarked on a speaking tour that summer. Brownlow argued that while it was common in Wesley's time for people to believe in ghosts, he provided evidence that many Presbyterian ministers still believed in such things. He derided Ross as a "habitual adulterer" and the son of a slave, and accused his relatives of stealing and committing indecent acts (Ross's son responded to the latter charge with a death threat). This quarrel continued until Brownlow moved to Knoxville in 1849.[8]

In 1856, James Robinson Graves, the Landmark Baptist minister of Nashville's Second Baptist Church, ripped Methodists in his book, The Great Iron Wheel, which used terminology and attacks similar to the ones Ross had used in the previous decade.[2]:67 Brownlow quickly fired back with The Great Iron Wheel Examined; Or, Its False Spokes Extracted, published that same year. He accused Graves of slandering an ex-Congressman, argued that Baptist ministers were mostly illiterate and opposed to learning, and charged that the Baptist religion was wrought with "selfishness, bigotry, intolerance, and shameful want of Christian liberality."[2]:73 Brownlow also mocked the Baptist sectarian method of baptism, Immersion.[2]:75

Slavery and secession

Brownlow's views on slavery changed over time. While his pre-Civil War writings reveal a strong pro-slavery slant, his name appears on an 1834 abolitionist petition.[11]:xiv In the early 1840s, Brownlow supported the American Colonization Society, which sought to recolonize freed slaves in Liberia.[2]:94 In subsequent years, however, he shifted to a staunchly pro-slavery stance. Brownlow's friend and colleague, Oliver Perry Temple, stated that social pressure in the 1830s pushed most abolitionist Southerners to adopt pro-slavery views. Historian Robert McKenzie, however, suggests that Brownlow's pro-slavery shift might have been rooted in the rivalry between Northern and Southern Methodists over the issue in the 1840s.[12]:38–39

By the 1850s, Brownlow was radically pro-slavery, arguing that the institution was "ordained by God."[12]:108 He gave a Scriptural defense of slavery in a speech delivered in Knoxville in 1857, and in the following year, he issued a challenge to Northern abolitionists to debate the issue. The challenge was initially accepted by Frederick Douglass, but Brownlow refused to debate him because of his race.[2]:97 The challenge was then taken up by Abram Pryne of McGrawville, New York, a clergyman with the Congregational Church, and editor of an abolitionist newspaper. At the debate, which took place in Philadelphia in September 1858, Brownlow stated in his opening argument:

Not only will I throughout this discussion openly and boldly take the ground that Slavery as it exists in America ought to be perpetuated, but that slavery is an established and inevitable condition to human society. I will maintain the ground that God always intended the relation of master and slave to exist; that Christ and the early teachers of Christianity, found slavery differing in no material respect from American slavery, incorporated into every department of society... that slavery having existed ever since the first organization of society, it will exist to the end of time.[13]

During the course of the Civil War, Brownlow would return to an anti-slavery stance, calling for emancipation.[12]:191

Brownlow was staunchly opposed to Southern secession.[2]:136 He argued that secessionists wanted to form a country governed by "purse-proud aristocrats" of the Southern planter class.[2]:135 Brownlow endorsed his friend, pro-Union candidate John Bell, for president in 1860, and in September of that year, interrupted a pro-Breckinridge rally in Knoxville to spar with the rally's keynote speaker, William Lowndes Yancey of Alabama.[12]:29 When South Carolina seceded following Lincoln's election in November 1860, Brownlow derided the state and its "miserable cabbage-leaf of a Palmetto flag" as being descended from British loyalists, thus giving it an affinity for the aristocratic types that would govern the proposed Southern Confederacy.[2]:140

By 1861, the Knoxville Whig had 14,000 subscribers,[2]:159 and was considered by secessionists the root of the stubborn pro-Union sentiment in East Tennessee (the region had resoundingly rejected a referendum on secession in February of that year). Knoxville's Democrats tried to counter Brownlow by installing radical secessionist J. Austin Sperry as editor of the Knoxville Register, touching off an editorial war that lasted throughout much of the year. Brownlow called Sperry a "scoundrel" and a "debauchee," and mocked the relatively small circulation of the Register.[9]:214

Throughout the Spring of 1861, Brownlow and his colleagues, Oliver Perry Temple, T.A.R. Nelson, and Horace Maynard, canvassed East Tennessee, giving dozens of pro-Union speeches. In May and June 1861, Brownlow represented Knox County at the East Tennessee Convention, which unsuccessfully petitioned the state legislature to allow East Tennessee to form a separate, Union-aligned state. In the weeks following Tennessee's secession in June 1861, Brownlow used the Whig to defend Unionists accused of treasonous acts by Confederate authorities. By the Fall of 1861, the Whig was the last pro-Union newspaper in the South.[12]:98

American Civil War

On October 24, 1861, Brownlow suspended publication of the Whig after announcing Confederate authorities were preparing to arrest him.[9]:254 On November 4, he left Knoxville and went into hiding in the Great Smoky Mountains to the south, where there was a strong pro-Union presence, and would spend several weeks staying with friends in Wears Valley and Tuckaleechee Cove. On November 8, pro-Union guerillas burned several railroad bridges in East Tennessee, and attacked several others. Confederate leaders immediately suspected Brownlow of complicity, but he denied any involvement in the attacks.[2]:182

Brownlow asked for permission to leave the state, which was granted by Confederate Secretary of War Judah P. Benjamin. On December 6, as he was in Knoxville preparing to leave, however, Knox County Commissioner Robert B. Reynolds and Confederate States District Attorney John Crozier Ramsey (a son of Confederate States treasury agent J. G. M. Ramsey, the elder who Brownlow earlier in that year referred to as "the vain old historian of Tennessee") arrested and jailed Brownlow on charges of treason. While jailed, Brownlow witnessed the trials and last moments of many of the condemned bridge-burners, which he recorded in a diary. He sent a letter to Benjamin protesting his incarceration, writing, "which is your highest authority, the Secretary of War, a Major General, or a dirty little drunken attorney such as J.C. Ramsey is!"[9]:318 After Benjamin threatened to pardon Brownlow, he was released in late December 1861.[2]:200

Brownlow was escorted to Nashville (which the Union Army had captured), and crossed over into Union-controlled territory on March 3, 1862. His struggle against secession had made him a celebrity in northern states, and he embarked upon a speaking tour, starting with speeches in Cincinnati and Dayton in early April. He spoke alongside Indiana governor Oliver P. Morton at Metropolitan Hall in Indianapolis on April 8, and spoke at the Merchants' Exchange in Chicago a few days later. On April 14, he addressed the Ohio state legislature in Columbus. He hosted a banquet at the Monongahela House in Pittsburgh on April 17, and spoke at Independence Hall in Philadelphia two days later.

In Philadelphia, publisher George W. Childs convinced Brownlow to write a book, Sketches of the Rise, Progress, and Decline of Secession, which was completed in May 1862. By September, the book had sold over 100,000 copies.[2]:239 Brownlow then headed to the northeast, where he addressed the New York City Chamber of Commerce on May 14, and spoke at the Academy of Music on May 15. In subsequent weeks, he spoke in Boston and various cities in New England, and later toured western New York and Illinois. In late June, he testified at the impeachment trial of West Hughes Humphreys, a Confederate judge who had denied Brownlow bail following his arrest in December.[2]:221–233

In June 1862, workers at the Colt Armory in Hartford presented a revolver to Brownlow's daughter, Susan, who had threatened to shoot two Confederate soldiers attempting to remove the American flag from the Brownlows' home in Knoxville in December of the previous year.[2]:230 Later that year, author Erastus Beadle published a dime novel, Parson Brownlow and the Unionists of East Tennessee. In 1863, Philadelphia-based music publisher Lee and Walker issued a musical score, Parson Brownlow's Quick Step.[2]:242–243

Brownlow returned to Nashville in early 1863, and followed Ambrose Burnsides's forces back to Knoxville in September. In November 1863, using proceeds from his speaking tour, he relaunched the Whig under the title, Knoxville Whig and Rebel Ventilator, and began vengefully pursuing ex-Confederates.[2]:251 He spent a portion of 1864 attempting to reorganize his church's Holston Conference and realign it with the northern Methodists.[2]:297

Reconstruction Era Governor of Tennessee

Brownlow was nominated for governor by a convention of Tennessee Unionists in January 1865. He was the only nominee. This convention also submitted state constitutional amendments outlawing slavery and repealing the Ordinance of Secession,[14] thus making his state the first of the Southern states to leave the Confederacy. The military governor, Andrew Johnson, had enacted a series of measures that essentially prevented ex-Confederates from voting, and on March 4, Brownlow was elected by a 23,352 to 35 vote, and the amendments passed by a similarly lopsided margin.[2]:261 The vote met President Lincoln's "1/10th test," which recognized elections in Southern states if the total vote was at least 1/10th the total vote in the 1860 presidential election.[2]:261

In early April 1865, Brownlow arrived in Nashville, a city which he despised, having called it a "dunghill," and stating it had a "deadly, treasonable exhalation."[15] He was sworn in April 5, and submitted the 13th Amendment for ratification the following day.[2]:265 After this amendment was ratified, Brownlow submitted a series of bills to punish former Confederates. He disfranchised for at least five years anyone who had supported the Confederacy, and, in cases of Confederate leaders, fifteen years. He later strengthened this law to require prospective voters to prove they had supported the Union. He tried to impose fines for wearing a Confederate uniform, and attempted to bar Confederate ministers from performing marriages.[2]:269

After a few months in office, Brownlow decided Johnson was too lenient toward former Confederate leaders, and aligned himself with the Radical Republicans, a group which dominated Congress and vehemently opposed Johnson. In the elections for the state's congressional seats held in August 1865, Brownlow tossed nearly one-third of the total vote to allow Radical candidate Samuel Arnell to win in the 6th District.[2]:280 A small group of state legislators, led by state Speaker of the House William Heiskell, turned against Brownlow, fearing his actions were too despotic, and aligned themselves with Johnson.[2]:309 By 1866, Brownlow had come to believe that some Southerners were plotting another rebellion, and that Andrew Johnson would be its leader.[16]

Opposition to the Klu Klux Klan

Brownlow began calling for civil rights to be extended to freed slaves, stating that "a loyal Negro was more deserving than a disloyal white man."[2]:291 In May 1866, he submitted the 14th Amendment for ratification, which the Radicals in Congress supported, but Johnson and his allies opposed. The Pro-Johnson minority in the state house attempted to flee Nashville to prevent a quorum, and the House sergeant-at-arms was dispatched to arrest them. Two were captured– Pleasant Williams and A.J. Martin– and confined to the House committee room, giving the House the necessary number of members present to establish a quorum. After the amendment passed by a 43-11 vote, Heiskell refused to sign it and resigned in protest. His successor signed it, however, and the amendment was ratified.[2]:314 In transmitting the news to Congress, Brownlow taunted Johnson, stating, "My compliments to the dead dog in the White House."[2]:315 Tennessee was readmitted to the Union shortly afterward.

The Radicals nominated Brownlow for a second term for governor in February 1867. His opponent was Emerson Etheridge, a frequent critic of the Brownlow administration. That same month, the legislature passed a bill giving the state's black residents the right to vote, and Union Leagues were organized to help freed slaves in this process. Members of these leagues frequently clashed with disfranchised ex-Confederates, including members of the burgeoning Ku Klux Klan, and Brownlow organized a state guard, led by General Joseph Alexander Cooper, to protect voters (and harass the opposition).[2]:333 With the state's ex-Confederates disfranchised, Brownlow easily defeated Etheridge, 74,848 to 22,548.[2]:339

By 1868, Klan violence had increased significantly. The organization had sent Brownlow a death threat, and had come close to assassinating Congressman Samuel Arnell.[2]:356 General Nathan B. Forrest joined the Klan, becoming its first Grand Wizard, partially in response to the disfranchisement policies of Brownlow.[16]

In an interview with the Cincinnati Commercial, Forrest stated, “I have never recognized the present government in Tennessee as having any legal existence.” He objected to Governor Brownlow calling out the militia and warned if they “committed outrages” that “they and Mr. Brownloe’s (sic) government will be swept out of existence not a Radical will be left alive.” Forrest claimed the Klan had more than 40,000 members in Tennessee and 550,000 in the southern states. He said the Klan supported the Democratic Party. Forrest suggested that a proclamation of Brownlow called for shooting members of the Klan. Forrest denied being a member of the Klan himself.[17]

Forrest and twelve other Klan members submitted a petition to Brownlow, stating they would cease their activities if Confederates were given the right to vote.[2]:360 Brownlow rejected this, however, and set about reorganizing the state guard and pressing the legislature for still greater enforcement powers.

Brownlow endorsed Ulysses S. Grant for president in 1868, and asked for federal troops to be stationed in 21 Tennessee counties to counter rising Klan activity. The state legislature granted him the power to throw out entire counties' voter registrations if he thought they included disfranchised voters. In October 1868, prior to the election, Brownlow discarded all registered voters in Lincoln County. Following the election, two of the Radicals' congressional candidates, Lewis Tillman in the 4th District and William J. Smith in the 8th District, were initially defeated. Brownlow, believing Klan intimidation to be the reason for their defeat, tossed the votes from Marshall and Coffee counties, allowing Tillman to win, and tossed the votes from Fayette and Tipton counties, allowing Smith to win.[2]:366–367

In February 1869, as Brownlow's final term was near its end, he placed nine counties under martial law, arguing it was necessary to quell rising Klan violence. He also dispatched five state guard companies to occupy Pulaski, where the Klan had been founded.[2]:372 After Brownlow left office in March, Forrest ordered the Klan to destroy its costumes and cease all activities.[16]

Later life

Following his reelection as governor in 1867, Brownlow decided he would not seek a third term, and instead sought the Senate seat that would be vacated by David T. Patterson, Andrew Johnson's son-in-law, in 1869. In October 1867, the state legislature elected Brownlow over William B. Stokes by a 63 to 39 vote.[2]:347 By the time he was sworn in on March 4, 1869, a persistent nervous disease had weakened him considerably, and the Senate clerk had to read his speeches.[2]:387 One of his speeches was a defense of Ambrose Burnside, the Union general who had liberated Knoxville from Confederate forces in 1863.[2]:390

After his Senate term ended in 1875, Brownlow returned to Knoxville. His successor as governor, DeWitt Clinton Senter, had undone most of his Radical initiatives, allowing Democrats to regain control of the state government.[18] Having sold the Whig in 1869, Brownlow purchased an interest in the Knoxville Chronicle, a Republican newspaper published by his old protégé, William Rule. The paper's name was changed to the Knoxville Whig and Chronicle.[2]:385 In 1876, Brownlow endorsed Rutherford B. Hayes for president.[2]:396 In December of the same year, he spoke at the opening of Knoxville College, which had been established for the city's African-American residents.[19]

On the night of April 28, 1877, Brownlow collapsed at his home, and died the following afternoon. The cause of death was given as "paralysis of the bowels."[2]:396 He was interred in Knoxville's Old Gray Cemetery following a funeral procession described by his colleague, Oliver Perry Temple, as the largest in the city's history up to that time.[20]

Legacy

In 1870, William Rule, who had been a journalist for the Whig, launched the Knoxville Chronicle, which he considered the Whig's pro-Republican successor. Rule continued editing this paper, which was eventually renamed the Knoxville Journal, until his death in 1928. The Knoxville Journal remained one of Knoxville's daily newspapers until it folded in 1991. Adolph Ochs, who later became publisher of the New York Times, began his career at the Chronicle in the early 1870s.[21]

William Rule wrote that Brownlow was "a master of invective and burning sarcasm, and he flourished in an age when such things were expected of a public journalist."[22] J. Austin Sperry, Brownlow's rival editor in pre-Civil War Knoxville, admitted that Brownlow was a remarkable judge of human nature.[23]

Brownlow's long-time colleague, Oliver Perry Temple, wrote of him:

It was easy for friends to persuade Mr. Brownlow to do anything that did not violate his sense of right; to force him was impossible. A child could lead him; a giant could not drive him. When his mind was once made up, it was as immovable as the mountains.[24]

Brownlow remained a divisive figure for decades after his death. In 1999, historian Stephen Ash wrote, "more than 120 years after his death, merely mentioning his name in the Volunteer State can evoke raucous laughter or bitter curses."[11]:xi Brownlow has been described as "Tennessee's worst governor," and the "most hated man in Tennessee History."[3] A 1981 poll of fifty-two Tennessee historians that ranked the state's governors on ability, accomplishments, and statesmanship, placed Brownlow dead last.[25]

Journalist Steve Humphrey argued that Brownlow was a talented newspaper editor and reporter, as evidenced by his reporting on events such as the opening of the Gayoso Hotel in Memphis and Knoxville's 1854 cholera epidemic.[23]

The Capitol Committee of the Tennessee General Assembly removed the official portrait of Governor William G. Brownlow that had only been briefly installed during April 1987 within the Legislative Library of state capitol building, upon the recommendation of Democrat Tennessee state Senator Douglas Henry.[26]

Family

Brownlow married Eliza O'Brien (1819–1914) during 1836 in Elizabethton, Tennessee. They had seven children: Susan, John Bell, James Patton, Mary, Fannie, Annie, and Caledonia Temple.[27] Eliza O'Brien Brownlow lived at the family's home on East Cumberland Avenue in Knoxville until her death in 1914 at the age of 94. In the 1890s and early 1900s, numerous visitors, including three presidents (William McKinley, Theodore Roosevelt, and William Howard Taft), called on Eliza Brownlow when visiting Knoxville.[26]

The Brownlows' older son, John Bell Brownlow (1839–1922), was a colonel in the Union Army during the Civil War. In the decades following his father's death, he helped finance the development of a Knoxville neighborhood (just north of modern Fourth and Gill) which for years was known as "Brownlow." Brownlow Elementary School, which served this neighborhood from 1913 to 1995, still stands, and has been converted into urban lofts.[28][29]

The Brownlows' younger son, James Patton Brownlow (1842–1879), was also a colonel in the Union Army during the Civil War, though he was later brevetted to brigadier general by President Andrew Johnson. He served as an adjutant general in the state guard during his father's term as governor.[30]

Walter P. Brownlow (1851–1910), a nephew of Parson Brownlow, served as a U.S. congressman from Tennessee's 1st district from 1897 until his death.[27] James Stewart Martin (1826–1907), another nephew of Parson Brownlow (the son of his sister, Nancy), served as a U.S. congressman from Illinois in the mid-1870s.[27] Louis Brownlow (1879–1963), a prominent 20th-century political scientist and city planner, was a grandson of one of Parson Brownlow's first cousins.[27] He served a tumultuous 3-year term as Knoxville's city manager in the 1920s.

Works

Newspapers

- The Whig, Brownlow's primary mouthpiece, was published under the following titles:

- Tennessee Whig (May 16, 1839 – 1840)

- The Whig (May 6, 1840 – November 3, 1841)

- Jonesborough Whig (November 10, 1841 – May 11, 1842)

- Jonesborough Whig and Independent Journal (May 18, 1842 – April 19, 1849)

- Brownlow's Knoxville Whig and Independent Journal (May 19, 1849 – April 7, 1855)

- Brownlow's Knoxville Whig (April 14, 1855 – July 27, 1861)

- Brownlow's Weekly Whig (August 3, 1861 – October 26, 1861)

- Brownlow's Knoxville Whig, and Rebel Ventilator (November 11, 1863 – February 21, 1866)

- Brownlow's Knoxville Whig (February 28, 1866 – January 27, 1869)

- Knoxville Weekly Whig (February 3, 1869 – March 1870)

- Weekly Whig and Register (c. 1870 – 1871)

- The Knoxville Whig and Chronicle (1875–1877), co-owner with William Rule

Books

- Helps to the Study of Presbyterianism: Or, An Unsophisticated Exposition of Calvinism, with Hopkinsian Modifications and Policy, with a View to a More Easy Interpretation of the Same (1834)

- Baptism Examined: Or, the True State of the Case (1842)

- A Political Register, Setting Forth the Principles of the Whig and Locofoco Parties in the United States, With the Life and Public Services of Henry Clay (1844)

- Americanism Contrasted with Foreignism, Romanism and Bogus Democracy, In the Light of Reason, History, and Scripture; In Which Certain Demagogues in Tennessee, and Elsewhere, are Shown Up in Their True Colors (1856)

- The Great Iron Wheel Examined; Or, Its False Spokes Extracted, and an Exhibition of Elder Graves, Its Builder (1856)

- Sketches of the Rise, Progress, and Decline of Secession; With a Narrative of Personal Adventures Among the Rebels (1862)

Speeches and debates

- "Speech, Being a Reply to Thomas Dog Arnold, Ass, Who Appeared Before the Invitation, On Saturday Night, the 18th of September, 1852, in the Hearing of a Large Audience, and Assailed Said Brownlow" (Knoxville, Tennessee, September 19, 1852)

- "A Sermon on Slavery: A Vindication of the Methodist Church, South: Her Position Stated" (Knoxville, Tennessee, August 9, 1857)

- "Ought American Slavery to be Perpetuated? A Debate Between Rev. W.G. Brownlow and Rev. A. Pryne Held At Philadelphia, September, 1858" (1858)

- "Speech of Parson Brownlow, of Tennessee, Against the Great Rebellion" (New York, May 15, 1862)

- "Address to the Loyal People of Tennessee" (Knoxville, Tennessee, March 18, 1868)

References

- 1 2 3 4 Forrest Conklin, William Gannaway "Parson" Brownlow. Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture, 2009. Retrieved: 18 October 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 E. Merton Coulter, William G. Brownlow: Fighting Parson of the Southern Highlands (Knoxville, Tenn.: University of Tennessee Press, 1999).

- 1 2 Jack Neely, "Requiem for Parson Brownlow," Metro Pulse, 6 April 2011. Accessed at the Internet Archive, 2 October 2015.

- ↑ Stephen V. Ash, "Introduction" in E. Merton Coulter, William G. Brownlow (Univ. of Tennessee Press, 1999) p xi

- 1 2 Paul Fink, Jonesborough: The First Century of Tennessee's First Town (Johnson City, Tenn.: Overmountain Press, 2002), pp. 140-145.

- 1 2 Jonesborough Whig and Independent Journal, 18 June 1845.

- ↑ Verton Queener, "William Gannaway Brownlow as an Editor," East Tennessee Historical Society Publications, No. 4 (1932), pp. 72-76.

- 1 2 3 Forrest Conklin and John Wittig, "Religious Warfare in the Southern Highlands: Brownlow versus Ross," Journal of East Tennessee History, Vol. 63 (1991), pp. 33-50.

- 1 2 3 4 William Gannaway Brownlow, Sketches of the Rise, Progress, and Decline of Secession (Philadelphia: G.W. Childs, 1862).

- ↑ James Bellamy, "The Political Career of Landon Carter Haynes," East Tennessee Historical Society Publications, Vol. 28 (1956), pp. 105-107.

- 1 2 Stephen Ash, Introduction to E. Merton Coulter's William G. Brownlow: Fighting Parson of the Southern Highlands (Chapel Hill, N.C.: University of North Carolina Press, 1999).

- 1 2 3 4 5 Robert McKenzie, Lincolnites and Rebels: A Divided Town in the American Civil War (New York: Oxford University Press, 2006).

- ↑ Brownlow, William Gannaway & Pryne, Abram Ought American slavery to be perpetuated?: A debate between Rev. W.G. Brownlow and Rev. A. Pryne. Held at Philadelphia, September, 1858 J.B. Lippincott & Co. (1858)

- ↑ Wilson D. Miscamble, "Andrew Johnson and the Election of William G. ('Parson') Brownlow as Governor of Tennessee," Tennessee Historical Quarterly, Vol. 37 (1978), pp. 308-320.

- ↑ Jesse Burt, Nashville: Its Life and Times (Tennessee Book Company, 1959), p. 67.

- 1 2 3 Phillip Langsdon, Tennessee: A Political History (Franklin, Tenn.: Hillsboro Press, 2000), pp. 169, 178, 190, 239.

- ↑ The Charleston Daily News. "A Talk with General Forrest." September 8, 1868: 1.

- ↑ William E. Hardy, "The Margins of William Brownlow's Words: New Perspectives on the End of Radical Reconstruction in Tennessee," Journal of East Tennessee History, Vol. 84 (2012), pp. 78-86.

- ↑ William MacArthur, Knoxville: Crossroads of the New South (Tulsa, Okla.: Continental Heritage Press, 1982), p. 49, 74.

- ↑ Oliver Perry Temple, Notable Men of Tennessee, From 1833 to 1875, Their Times and Their Contemporaries (New York: Cosmopolitan Press, 1912), p. 143.

- ↑ Doris Faber, Printer's Devil to Publisher: Adolph S. Ochs of the New York Times (New York Messner, 1963), pp. 24-25.

- ↑ William Rule, Standard History of Knoxville, Tennessee (Chicago: Lewis Publishing Company, 1900; reprinted by Kessinger Books, 2010), p. 326.

- 1 2 Stephen Humphrey, "The Man Brownlow from a Newspaper Man's Point of View," East Tennessee Historical Society Publications, Vol. 43 (1971), pp. 59-70.

- ↑ Temple, Notable Men of Tennessee, p. 282.

- ↑ Tennessee Historical Quarterly, Vol. 41, No. 1 (Spring 1982), p. 100.

- 1 2 Jack Neely, "Gov. Brownlow's Bad Reputation," Metro Pulse, 6 April 2011. Accessed at the Internet Archive, 2 October 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 Zella Armstrong, Notable Southern families, Volume 1, (Chattanooga, Tenn.: The Lookout Publishing Co., 1918), pp. 39-45. OCLC 1079125. Retrieved: 29 October 2012.

- ↑ Knox County Development Corporation, Brownlow School Redevelopment & Urban Renewal Plan, August 2007. Retrieved: 29 October 2012.

- ↑ Brownlow Lofts. Retrieved: 29 October 2012.

- ↑ Roger D. Hunt and Jack R. Brown, Brevet Brigadier Generals in Blue (Gaithersburg, Maryland: Olde Soldier Books, Inc., 1990), p. 86. ISBN 1-56013-002-4.

Further reading

- Ash, Stephen (1999), Secessionists and Scoundrels, Louisiana State University Press, ISBN 0-8071-2354-4

- Robert Booker, "Brownlow Roared Pro-Union Message, Knoxville News Sentinel, 28 June 2011.

- Coulter, E. Merton, William G. Brownlow: Fighting Parson of the Southern Highlands (1999). Appalachian Echoes. Full text online

- Downing, David C. (2007), A South Divided: Portraits of Dissent in the Confederacy. Nashville: Cumberland House, ISBN 978-1-58182-587-9

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to William Gannaway Brownlow. |

- United States Congress. "William Gannaway Brownlow (id: b000963)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

- Brownlow's Knoxville Whig and Rebel Ventilator – from the Library of Congress "Chronicling America" database; includes issues published 1863–1866

- William Gannaway Brownlow entry at the National Governors Association

- Governor William G. Brownlow Papers – Tennessee State Library and Archives

- Brownlow-related photographs in the Calvin McClung Digital Collection – includes newspaper clippings and family photos

- William Gannaway Brownlow entry at The Political Graveyard

- Works by William Gannaway Brownlow at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about William Gannaway Brownlow at Internet Archive

- William Gannaway Brownlow at Find a Grave

| Political offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Edward H. East Acting Governor |

Governor of Tennessee 1865–1869 |

Succeeded by Dewitt Clinton Senter |

| United States Senate | ||

| Preceded by David T. Patterson |

U.S. Senator (Class 1) from Tennessee 1869–1875 Served alongside: Joseph S. Fowler, Henry Cooper |

Succeeded by Andrew Johnson |