William Apess

William Apess (1798–1839) (also William Apes before 1837), was an ordained Methodist minister, writer, and activist of mixed-race descent, who was a political and religious leader in Massachusetts. After becoming ordained as a Methodist minister in 1829, he published his autobiography the same year. It is among the first autobiographies by a Native American writer. Apess was part Pequot Indian.

An itinerant preacher in New England, Apess visited the Mashpee on Cape Cod in 1833. Hearing their grievances against white overseers and settlers who stole their wood, he helped organize what was called the Mashpee Revolt of 1833-34. Their attempt to regain civil rights was covered sympathetically by the Boston Advocate, while criticized by local journals in Cape Cod. Apess published a book about the experience in 1835, which he summarized as "Indian Nullification." Apess alienated many of his supporters before dying in New York City, New York at age 41, although he has been described as "perhaps the most successful activist on behalf of Native American rights in the antebellum United States."[1]

Early life

William Apess was born in 1798 in Colrain in northwestern Massachusetts to William and Candace Apess of the Pequot tribe.

According to his autobiography, Apess' paternal grandfather was white and married a Pequot woman.[2][3] He claimed descent from King Philip through his mother, who also had European-American and African ancestry.[4] Until the age of five, Apess lived with his family, including two brothers and two sisters, near Colrain.[5]

After his parents separated, the children were cared for by their maternal grandparents, who were abusive and suffered from alcoholism. After continued abuse, a neighbor intervened with the town selectmen on behalf of the children. They were taken away for their own safety and indentured to European-American families. The then five-year-old Apess was cared for by his neighbor, Mr. Furman, for a year until he had recovered from injuries sustained while living with his grandparents. His autobiography does not mention any contact with his Pequot relatives for the rest of his childhood. He remarks that he did not see his mother for twenty years after the beating. In contrast, he grew to love his adopted family dearly, despite his status as an indentured servant. When Mrs. Furman’s mother died, he writes that “She had always been so kind to me that I missed her quite as much as her children, and I had been allowed to call her mother."[6] Apess was sent to school during the winter for six years to gain an education, while also assisting Furman at work.[5][7] Mrs. Furman, a Baptist, gave William his first memorable experience with Christianity when he was six, and she discussed with him the importance of going to heaven or hell. Even as a young child, his devotion was ardent. He describes the joy he gained from sermons, and the deep depression he suffered when Mr. Furman eventually forbade him from attending.[8]

William was brutally shocked out of this happy period of his life at age eleven, when Mr. Furman discovered his plans to run away. He never really wanted to leave, but, despite his reassurances, the family he had come to regard as his own sold him to Judge James Hillhouse, a member of the Connecticut elite. The elderly judge, being much too old to discipline an unruly and rejected child, quickly sold his indenture to Gen. William Williams, under whom Apess spent four years. It was during these four years that Apess grew increasingly close to the “noisy Methodists,” a community composed mostly of mixed-race, black, or poor people considered outcasts.[9]

Apess ran away at the age of fifteen and joined a militia in New York, fighting in the War of 1812. By the age of 16, he became an alcoholic and struggled with alcoholism for the rest of his life. From the years 1816 to 1818, he worked at various jobs in Canada.

Troubled by his alcoholism, Apess decided to return home to the Pequot and his family. Within a short period of time, he reclaimed his Pequot identity. He attended meetings of local Methodist groups and was baptized in December 1818.

Personal life

In 1821, Apess married Mary Wood, also of mixed race. The couple had one son and three daughters together.[5] After Mary died, Apess later remarried. He and his second wife settled in New York City in the late 1830s.

Career

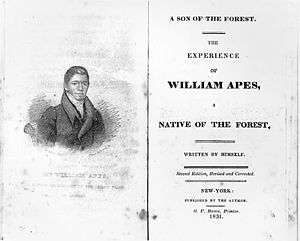

After his marriage to Mary, Apess felt his vocation was to preach. In 1829 he was ordained as a Protestant Methodist minister, a group he found less hierarchical and rule bound than the Methodist Episcopal Church.[10] In the same year he published his autobiography, A Son of the Forest: The Experience of William Apess, A Native of the Forest, Comprising a Notice of the Pequot Tribe of Indians, Written by Himself. Apess' work was one of the first autobiographies published by a Native American and was published partly in reaction to advocates of Indian Removal, including Andrew Jackson. He used the common format of the time of the spiritual conversion to comment also on European-American prejudices against Native Americans.[11]

As was the Methodist practice of the day, Apess became an itinerant preacher; he preached in meetings throughout New England to mixed congregations including Native American, European-American, and African-American audiences. While preaching in the Wampanoag dialect of the Algonquian language family, he used English language and cultural precepts to raise issues of Indian rights to European-American audiences and "to serve Indian political ends."[1] In 1833, following a visit to the town of Mashpee, the largest Native American town in Massachusetts, Apess became convinced the State was acting illegally in denying self-government to the Mashpee Wampanoag.

The Mashpee Wampanoag had a close culture and wooded land at the elbow of Cape Cod. They had been placed under supervision by white overseers, who were allowing white settlers to take their wood and permitted other incursions on their land. The Mashpee wanted to protect their grounds. Apess spoke out on their behalf at local meetings. He also participated in the so-called Mashpee Revolt of 1833-34, in which the Mashpee took action to restore their self-government: they wrote to the state government announcing their intention to rule themselves, according to their constitutional rights, and to prevent whites from taking away their wood (a recurring problem). In May 1833, the Mashpee tribe wrote to Harvard College, which administered the Williams Fund that paid for a minister to them. The tribe had never been consulted in such appointment and objected to Rev. Mr. Fish, who had long been appointed to them. They did not like his preaching, and said that he had enriched himself by appropriating hundreds of acres of woodland at the tribe's expense.[12] Lastly, they prevented a settler, William Sampson, from taking wood away from their property and unloaded his wagon. Three Indians were indicted for riot and Apess was jailed for a month as a result.[13] An attorney assisted them in successfully appealing to the legislature, but initially Governor Levi Lincoln, Jr. threatened the group with military force.

The issues were reported sympathetically by Harnett of the Boston Advocate through June and July.[14] The Mashpee protest followed the Nullification Crisis of 1832 on the national level, and the historian Barry O'Connell suggests that Apess intended to highlight the Mashpee attempt to nullify Massachusetts laws discriminating against Native peoples.[15] Apess continually drew parallels between the desire of people of color for their rights, particularly Native Americans, and the historic struggle of European-American colonists for independence. He drew from the history of relations between Native Americans and the colonists, as well as relations within the United States.

During the period 1831-1836, Apess published several of his sermons and public lectures, and became known as a powerful speaker. But, struggling with alcoholism and increasing resentment of white treatment of Natives, he gradually lost the respect in which he had been held; both white and Mashpee groups distanced themselves from him. In 1836, he gave a public lecture in the form of a memorial eulogy for King Philip, a seventeenth-century Indian leader who was assassinated by the Plymouth colonists. Apess extolled him as a leader equal to any among the European Americans. He had been killed after the colonists had poisoned his brother and violated several treaties. Philip's head was stuck on a stake and his hands cut off, given as presents to the spies that betrayed him.

After publishing his lecture, Apess disappeared from New England public life. He moved to New York City with his wife and children, trying to find work. The recession of 1837 was broadly damaging and especially affected the lower and working classes, so he struggled in New York.

Death

At the age of 41, William Apess died of a cerebral hemorrhage (stroke) on April 10, 1839 at 31 Washington Street in New York City.[16] He lived there with his second wife.

Quotes

- "I felt convinced that Christ died for all mankind – that age, sect, color, country, or situation make no difference. I felt an assurance that I was included in the plan of redemption with all my brethren." – A Son of the Forest

- "As the immortal Washington lives endeared and engraven on the hearts of every white in America, never to be forgotten in time – even such is the immortal Philip honored, as held in memory by the degraded but yet graceful descendants who appreciate his character." – Eulogy on King Philip (Metacom)

- "Is it not because there reigns in the breast of many who are leaders a most unrighteous, unbecoming, and impure black principle, and as corrupt and unholy as it can be – while these very same unfeeling, self-esteemed characters pretend to take the skin as a pretext to keep us from our unalienable and lawful rights?" – An Indian's Looking-Glass For The White Man

Bibliography

- A Son of the Forest: The Experience of William Apes, A Native of the Forest, Comprising a Notice of the Pequod Tribe of Indians, Written by Himself (1829), full text available in download, at Internet Archive.

- The Increase of the Kingdom of Christ, a Sermon (1831).

- The Experiences of Five Christian Indians of the Pequod Tribe; or An Indian's Looking-Glass for the White Man (1833), at Internet Archive.

- The Indian Nullification of the Unconstitutional Laws of Massachusetts, Relative to the Marshpee Tribe: or, The Pretended Riot Explained (1835), at Internet Archive.

- Eulogy on King Philip, as Pronounced at the Odeon, in Federal Street, Boston, by the Rev. William Apes, an Indian (1836), download at Internet Archive.

See also

Notes

- 1 2 Bizzell, Patricia. "(Native) American Jeremiad: The 'Mixedblood' Rhetoric of William Apess", in Stromberg, Ernest. ed. American Indian Rhetorics of Survivance: Word Medicine, Word Magic, Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2006

- ↑ Barry O'Connell, ed., A Son of the Forest and Other Writings, University of Massachusetts, 1997, p. 3

- ↑ O'Connell, Barry, ed. On Our Own Ground: The Complete Writings of William Apess, a Pequot, N.P.: University of Massachusetts Press, 1992, p. 314

- ↑ O'Connell, Barry, American National Biography, Vol. 1. New York: Oxford University, 1999, p. 555

- 1 2 3 Reuben, Paul P. "Chapter 3: William Apes or William Apess (Pequot) (1798-1839)", Perspectives in American Literature. 24 Dec 2010 (retrieved 13 Sept 2011)

- ↑ William Apess, "A Son of the Forest," 1829

- ↑ Barry O'Connell, ed., A Son of the Forest and Other Writings, University of Massachusetts, 1997, pp. 5-7

- ↑ William Apess, "A Son of the Forest," pp. 28, 1829

- ↑ William Apess, "A Son of the Forest," pp. 39

- ↑ O'Connell (1997), A Son of the Forest, p. 3

- ↑ O'Connell (1997), A Son of the Forest, pp. 2-3

- ↑ O'Connell (1992), "Indian Nullification," in On Our Own Ground, pp. 175-179

- ↑ O'Connell (1992), "Indian Nullification," in On Our Own Ground, p. 167

- ↑ O'Connell (1992), "Indian Nullification," in On Our Own Ground, pp. 200-201

- ↑ O'Connell (1992), "Indian Nullification," in On Our Own Ground, p. 163

- ↑ Konkle, Maureen. Writing Indian Nations: Native Intellectuals and the Politics of Historiography, 1827-1863, Chapel Hill: U of North Carolina Press, 2004, p. 106 passim

Further reading

- Brooks, Lisa. The Common Pot: The Recovery of Native Space in the Northeast, Minneapolis: U of Minnesota Press, 2008.

- Carlson, David J. Sovereign Selves: American Indian Autobiography and the Law, Urbana: U of Illinois Press, 2006.

- Doolen, Andy. Fugitive Empire: Locating Early American Imperialism, Minneapolis: U of Minnesota Press, 2005.

- Elrod, Eileen R. Piety and Dissent: Race, Gender, and Biblical Rhetoric in Early American Autobiography, Amherst: U of Massachusetts Press, 2008.

- Gura, Philip F. The Life of William Apess, Pequot (University of North Carolina Press, 2015)

- Peyer, Bernd C. The Tutor'd Mind: Indian Missionary-Writers in Antebellum America. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press,1997.

- Tiro, Karim M., "Denominated "Savage": Methodism, Writing and Identity in the Works of William Apess, A Pequot," American Quarterly, American Studies Association, 1996.