West Belarus

| West Belarus | |

|---|---|

|

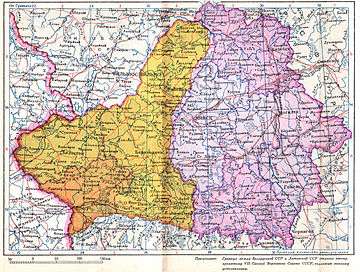

Administrative division of the Byelorussian SSR (green) before World War II with territories annexed by the USSR from Poland in 1939 (marked in shades of orange), overlaid with territory of present-day Belarus  | |

West Belarus in 1939 shown in dark green | |

| Country | Belarus, partly in Poland and Lithuania |

| Area | Historical region |

| Today part of | Hrodna, Brest, Minsk (partially) and Vitsebsk (partially); Podlasie Voivodeship (partially), South Western areas of the Republic of Lithuania including Vilnius |

West Belarus (Belarusian: Заходняя Беларусь, Zakhodnyaya Belarus) is a historical region of modern-day Belarus; comprising the territory which belonged to the Second Polish Republic during the interwar period in accordance with the international peace treaties. It used to form the northern half of the Polish Kresy Wschodnie macroregion before the 1939 Nazi-Soviet invasion of Poland (the Eastern Borderlands).[1] Following the end of World War II in Europe the territory of West Belarus was ceded to the USSR by the Allied Powers, while the city of Białystok with surroundings was returned to Poland. Until the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991 West Belarus formed a significant part of the Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republic. Today, it constitutes the western half of the sovereign Republic of Belarus.[2]

West Belarus includes Hrodna and Brest voblasts (see map), as well as parts of today's Minsk and Vitsebsk voblasts. The city of Wilno (Belarusian: Вільня, Vilnia, today's Vilnius), also included in the BSSR, was given by the USSR to the Republic of Lithuania which soon after that became the Lithuanian SSR.[3]

Background

The territories of Belarus, Poland, Ukraine, and the Baltic states were a major theatre of operations during World War One; all the while, the Bolshevik Revolution overturned the interim Russian Provisional Government and formed the Soviet Russia. The Bolsheviks withdrew from the tsarist war with the Central Powers by signing the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk,[4] and ceded Belarus to Germany for the next eight and a half months. The German high command used this window of opportunity to transfer its troops to the Western Front for the 1918 Spring Offensive, leaving behind a power vacuum.[5] The non-Russians, who inhabited the lands given by the Soviets to imperial Germany, saw the treaty as an opportunity to set up independent states under the German umbrella. Three weeks after the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk was signed on 3 March 1918 the newly-formed Belarusian Central Council declared the founding of the Belarusian People's Republic across the territory of modern-day Belarus. The idea was rejected by the Germans and by the Bolsheviks as well. For the American delegation led by Wilson, this was also unacceptable; the Americans intended to protect the territorial integrity of European Russia.[4]

The fate of the region was not settled for the following three and a half years. The Polish–Soviet War which erupted in 1919 was particularly bitter; it ended with the Treaty of Riga signed in 1921.[1] Poland and the Baltic states emerged as independent countries opposite the USSR. The territory of modern-day Belarus was split by the treaty into the Polish West Belarus and the Soviet East Belarus, with the border town in Mikaszewicze.[6][7] Notably, the peace treaty was signed with the full active participation of the Belarusian delegation on the Soviet side.[8] Poland abandoned all rights and claims to the territories of Soviet Belarus (paragraph 3), while the Soviet Russia abandoned all rights and claims to Polish Western Belarus.[8]

Rada of the Belarusian Democratic Republic in Exile

_Map_1918.jpg)

As soon as the Soviet-German peace treaty was signed in March 1918, the newly formed Rada of the Belarusian Democratic Republic laid territorial claims to Belarus based on areas specified in the Third Constituent Charter unilaterally as inhabited by the Belarusian majority. The same Rada charter also declared that the Treaty of Brest-Litowsk of March 1918 was invalid because it was signed by foreign governments partitioning territories which were not theirs.[9] Allegedly, the outline of the republic was based on the works of Belarusian ethnographers Yefim Karsky (1903) and Mitrofan Dovnar-Zapol'skiy (1919). In the Second Constituent Charter the Rada abolished the right to private ownership of land (paragraph 7) in line with the Communist Manifesto.[9] Meanwhile, by 1919 the Bolsheviks took control over large parts of Belarus and forced the Belarusian Rada into exile in Germany. The Bolsheviks formed the Soviet Socialist Republic of Belarus during the war with Poland on roughly the same territory claimed by the Belarusian Republic.[10]

The new Polish-Soviet border was internationally recognized as well as ratified by the League of Nations.[1] The peace agreement remained in place throughout the interwar period. The borders established between the two countries remained in force until the outbreak of World War II, and the 17 September 1939 Soviet invasion of Poland. They were later redrawn during the Yalta Conference and the Potsdam Conference on the insistence of Joseph Stalin.[1]

Second Polish Republic

According to the first Polish national census of 1921, there were around 1 million Belarusians in the country. There are historians who estimate the number of Belarusians in Poland at that time to be perhaps 1.7 million or even up to 2 million.

In the years that followed the Peace of Riga thousands of Poles settled in the area, many of them (including veterans of armed struggle for Poland's independence) were given land by the government (see Osadnik).[11]

In the elections of November 1922, a Belarusian party (in the Blok Mniejszości Narodowych coalition) obtained 14 seats in the Polish parliament (11 of them in the lower chamber, Sejm). In the spring of 1923, Polish prime minister Władysław Sikorski ordered a report on the situation of the Belarusian minority in Poland. That summer, a new regulation was passed allowing for the Belarusian language to be used officially both in courts and in schools. Obligatory teaching of the Belarusian language was introduced in all Polish gymnasia in areas inhabited by Belarusians in 1927.

Polonization

According to the Riga Peace Treaty, the Polish government was obliged to guarantee rights of ethnic Belarusians to develop their culture and language.[12] However, in practice these rights were constantly violated, according to Per Anders Rudling[13] and a 2015 high school course by A.A. Goloburda.[12]

A major part of the West Belarusian population received the annexation of West Belarus by Poland with apathy and scepticism.[14] The Polish military treated the local population badly.[15] The Polish administration often introduced harsh repressive measures (pacyfikacja) against the West Belarusian population.[16]

Józef Piłsudski had negotiations with the West Belarusian political leadership[17] but unlike the Soviets the Polish government eventually refused to grant the former Western part of the Belarusian People's Republic any, even symbolic, form of autonomy within the Polish national state and abandoned the earlier ideas of creating a federal state on the lands of the former Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth.[18]

Following the intentions of the majority of the Polish society of the region,[18] the Polish government introduced harsh policies of polonization and assimilation of Belarusians in West Belarus.[19] The Polish official Leopold Skulski, an advocate of polonization policies, is being quoted as saying in the Sejm: "I assure you that in some ten years you won't be able to find a single [ethnic] Belarusian [in West Belarus]"[20][21][22].

The radical and often polonization policies were inspired and influenced by the Polish nationalistic political movement National Democracy led by Roman Dmowski, who promoted the assimilation of Belarusians and Ukrainians, refusing them the right for a free national development and referring to them as the "inferior type of Poles" (Polish: gorszy gatunek Polaków).[23] Since the May Coup (Poland) the nationalists lost their influences, the radical nationalists were imprisoned in Bereza Kartuska prison.

Władysław Studnicki, an influential Polish official at the administration of the Kresy region 1919-1920, openly stated that Poland needed the Eastern regions as an object for colonization.[24]

Belarusian media in Poland faced increased pressure and censorship from the authorities.[25] Out of 23 Belarusian newspapers and magazines published in 1927, by 1933 only 8 were left five years later.[26]

There widespread cases of discrimination of the Belarusian language,[27] it was forbidden for usage in state institutions.[26]

Orthodox Christians also faced discrimination in interwar Poland.[26] This discrimination was also targeting assimilation of Eastern Orthodox Belarusians.[28] The Polish authorities were imposing Polish language in Orthodox church services and ceremonies,[28] initiated the creation of Polish Orthodox Societies in various parts of West Belarus (Slonim, Bielastok, Vaŭkavysk, Navahrudak).[28]

Belarusian Roman Catholic priests like Fr. Vincent Hadleŭski[28] who promoted Belarusian language in the church and Belarusian national awareness were also under serious pressure by the Polish regime.[28] The Polish Catholic Church issued documents to priests prohibiting the usage of the Belarusian language rather than Polish language in Churches and Catholic Sunday Schools in West Belarus. A 1921 Warsaw-published instruction of the Polish Catholic Church criticized the priests introducing the Belarusian language in religious life: "They want to switch from the rich Polish language to a language that the people themselves call simple and shabby".[29]

Before 1921, there were 514 Belarusian language schools in West Belarus.[16] In 1928, there were only 69 schools which was just 3% of all existing schools in West Belarus at that moment.[30] All of them were phased out by the Polish educational authorities by 1939,.[12][16] because the attendance was minimal due in part to lower quality of instruction. The Polish officials openly prevented the creation of Belarusian schools and were imposing Polish language in school education in West Belarus.[31] The officials explained this with the fact that the limited edition of a first-ever textbook of Belarusian grammar was written no earlier that 1918.[32] The Polish officials often treated any Belarusian demanding schooling in Belarusian language as a Soviet spy and any Belarusian social activity as a product of a communist plot.[33]

The Belarusian civil society resisted polonization and mass closure of Belarusian schools. The Belarusian Schools Society (Belarusian: Таварыства беларускай школы), led by Branisłaŭ Taraškievič and other activists, was the main organization promoting education in Belarusian language in West Belarus in 1921-1937.

According to Belarusian historians, the authoritarian Polish regime used mass arrests and tortures against the population of West Belarus[26] which has provoked protests[26] from the population and increased the loyalty of West Belarusians towards the Soviet Union. In the 1920s, Belarusian partisan units arose in many areas of West Belarus, mostly unorganized but sometimes led by activists of Belarusian left wing parties.[26] In the spring of 1922, several thousands Belarusian partisans issued a demand to the Polish government to stop the violence, to liberate political prisoners and to grant autonomy to West Belarus.[26] Protests were held in various regions of West Belarus until mid 1930s.[26]

Hramada

.svg.png)

Compared to the (larger) Ukrainian minority living in Poland, Belarusians were much less politically aware and active. The largest Belarusian political organization was the Belarusian Peasants' and Workers' Union, also refereed to as the Hramada.

Hramada received logistical help from the USSR and Comintern and was a cover for the more radical illegal Communist Party of West Belarus. It was therefore banned by the Polish authorities,[34][35] its leaders were sentenced to various terms in prison and then handed out to the USSR, where they were killed by the Soviet regime[36]

Tensions between the increasingly nationalistic Polish government and various increasingly separatist ethnic minority groups continued to grow, and the Belarusian minority was no exception. Likewise, according to Marek Jan Chodakiewicz, the USSR considered Poland to be "enemy number one".[37] During the Great Soviet Purge, the Polish Autonomous District at Dzyarzhynsk (Polish: Kojdanów) was disbanded and the Soviet NKVD undertook the so-called "Polish Operation" (from approximately August 25, 1937 to November 15, 1938) – a program of deportation and shootings that targeted Poles in East Belarus.[37] The operation caused the deaths of to 250,000 people – out of an official ethnic Polish population of 636,000 – as a result of political murder, disease or starvation.[37] Amongst these, at least 111,091 members of the Polish minority were shot by NKVD troykas.[37][38][39] Many were murdered in prison executions, according to Bogdan Musial.[38] In addition, several hundred thousand ethnic Poles from Belarus and Ukraine were deported to other parts of the USSR.[37]

The Soviets also promoted Soviet-controlled East Belarus as formally autonomous, in order to attract Belarusians living in Poland. This image was attractive to many West Belarusian national leaders and some of them, like Francišak Alachnovič or Uładzimir Žyłka emigrated from Poland to East Belarus, but very soon became victims of Soviet repression.

In 1939, the Soviet invasion of Poland was portrayed by Soviet propaganda as the "liberation of West Belarus and Ukraine". Many ethnic Belarusians initially welcomed unification with the Belorussian SSR, but changed their attitude after experiencing the Soviet system. From 1939 on, with the exception of a brief period of Nazi occupation, almost all Belarusians previously living in Poland would live in the Belorussian SSR.[40][41]

Soviet invasion of Poland

Soon after the Nazi-Soviet Invasion of Poland in September of 1939, the area of West Belarus was annexed into the Belarusian Soviet Socialist Republic following staged elections decided by the NKVD in the atmosphere of complete terror.[42] The citizens were told repeatedly that the deportations to Siberia were imminent. Their ballot envelopes were numbered so as to remain traceable.[42]

Annexation of West Belarus by the USSR

.jpg)

The Soviet occupational administration organized their elections into a National assembly of West Belarus (Belarusian: Народны сход Заходняй Беларусі) on October 22, 1939, less than two weeks after the invasion. The so-called Elections to the People's Assemblies of Western Ukraine and Western Belarus took place under total control of the NKVD secret police and the Party agents from Russia. At times, the Belarusian civilians extracted from homes were brought to the voting halls under armed escorts. Their envelopes were numbered and oftentimes already sealed.[42] On October 30, the National Assembly session held in Belastok passed the decision of West Belarus joining the USSR and its unification with the Belarusian Soviet Socialist Republic. These petitions were officially accepted by the Supreme Soviet of the USSR on November 2 and by the Supreme Soviet of the BSSR on November 12.[43]

However, the Soviet rule was short-lived. The corresponding terms of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact signed earlier in Moscow were broken, when the German Army entered the Soviet occupation zone on June 22, 1941 (see German invasion of Poland and Soviet invasion of Poland) After Operation Barbarossa, most of West Belarus became part of the Generalbezirk of Belarus, part of Reichskommissariat Ostland.

Two years later, at the insistence of Joseph Stalin during the Tehran Conference of 1943, the Allies formally agreed that most of West Belarus would remain part of the Belorussian SSR after the end of World War II in Europe. Only the region around Białystok (Belostok, Biełastok) was to be returned to Poland.

The Polish population was soon forcibly resettled.[2] West Belarus in its entirety was incorporated into the Byelorussian SSR (BSSR).

It was initially planned to move the capital of the Byelorussian SSR to Vilnius. However, the same year Joseph Stalin ordered that the city and surrounding region be transferred to Lithuania, which some months later was annexed by the Soviet Union and became a new Soviet Republic. Minsk therefore was proclaimed the capital of the enlarged BSSR. The borders of the BSSR were again altered somewhat after the war (notably the area around the city of Białystok (Belastok Voblast) was returned to Poland) but in general they coincide with the borders of the modern Republic of Belarus.

Collectivization, deportations and ethnic cleansing

The Belarusian political parties and the society in West Belarus often lacked information about repressions in the USSR and was under strong influence of Soviet propaganda.[28] Because of bad economic conditions and national discrimination of Belarusian in Poland, much of the population of West Belarus welcomed the annexation by the USSR.[28]

However, soon after the annexation of West Belarus by the USSR, the Belarusian political activists had no illusions as to the friendliness of the Soviet regime.[28] The population grew less loyal as the economic conditions became even worse and as the new regime carried out mass repressions and deportations that targeted Belarusians as well as ethnic Poles.[28]

Immediately after the annexation, the Soviet authorities carried out the nationalization of agricultural land owned by large landowners in West Belarus.[28] Collectivization and the creation of collective farms (kolkhoz) was planned to be carried out on a more slow pace than in East Belarus in the 1920s.[28] By 1941, in the western regions of the BSSR the number of individual farms decreased only by 7%; 1115 collective farms were created.[28] At the same time, pressure and even repressions against larger farmers (called by the Soviet propaganda, kulaki) began: the size of agricultural land for one individual farm was limited to 10ha, 12ha and 14ha dependind on quality of the land.[28] It was forbidden to hire workers and to lease land.[28]

Under the Soviet occupation, the Western Belarusian citizenry, particularly the Poles faced a "filtration" procedure by the NKVD apparatus, which resulted in over 100,000 people forcibly deported to eastern parts of the USSR (i.e. Siberia) in the very first wave of expulsions.[44] In total, during the next two years some 1.7 million Polish citizens were put on freight trains and sent from the Polish Kresy to labour camps in the Gulag.[45]

Legacy

Presently, Belarus unofficially celebrates September 17 as the Day of reunification of West Belarus and the BSSR. Nevertheless, there are different opinions regarding this date in the Belarusian society.[46][47]

See also

- Second Polish Republic

- Kresy

- Western Ukraine

- Soviet raid on Stołpce

- Border Protection Corps

- Siarhei Prytytski

Notes

References

- 1 2 3 4 Prof. Anna M. Cienciala (2004). "The Rebirth of Poland". History 557: Poland and Soviet Russia: 1917-1921. The Bolshevik Revolution, the Polish-Soviet War, and the establishment of the polish-soviet frontier. University of Kansas (Lecture Notes 11 B). Retrieved 31 July 2016 – via Internet Archive.

- 1 2 Piotr Eberhardt; Jan Owsinski (2003). Ethnic Groups and Population Changes in Twentieth-century Central-Eastern Europe: History, Data, Analysis. M.E. Sharpe. pp. 199–201. ISBN 978-0-7656-0665-5.

- ↑ Ronen, Yaël (2011). Transition from Illegal Regimes Under International Law. Cambridge University Press. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-521-19777-9.

- 1 2 Ruth Fischer (2006) [1948]. Stalin and German Communism. Transaction Publishers. pp. 32, 33–36. ISBN 1412835011.

- ↑ Smithsonian (2014). World War I: The Definitive Visual History. Penguin. p. 227. ISBN 1465434909.

- ↑ Adam Daniel Rotfeld, Anatoly V. Torkunov (2015). White Spots—Black Spots: Difficult Matters in Polish-Russian Relations, 1918–2008. University of Pittsburgh Press. p. 64. ISBN 0822980959.

- ↑ Janusz Cisek (2002). Kosciuszko, We Are Here!: American Pilots of the Kosciuszko Squadron in Defense of Poland, 1919-1921. McFarland. p. 91. ISBN 0786412402.

- 1 2 Michael Palij (1995). The Ukrainian-Polish Defensive Alliance, 1919-1921: An Aspect of the Ukrainian Revolution. CIUS Press. p. 165. ISBN 1895571057.

- 1 2 Executive Committee; Ivonka J. Survilla, President (9 March 1918). "Council of BNR". Rada of the Belarusian Democratic Republic in Exile. First, Second, and Third Constituent Charter.

Mensk, 21 (8) February 1917 – 25 March 1918

- ↑ Map of the Soviet Socialist Republic of Belarus on JiveBelarus.net website.

- ↑ Alice Teichova, Herbert Matis, Jaroslav Pátek (2000). Economic Change and the National Question in Twentieth-century Europe. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-63037-5.

- 1 2 3 Матэрыялы для падрыхтоýкі да абавязковага экзамену за курс сярэняй школы: Стан культуры у Заходняй Беларусі у 1920-я-1930-я гг: характэрныя рысы і асаблівасці

- ↑ Per Anders Rudling (2014). The Rise and Fall of Belarusian Nationalism, 1906–1931. University of Pittsburgh Press. p. 183.

- ↑ Mironowicz, Eugeniusz (2007). Białorusini i Ukraińcy w polityce obozu piłsudczykowskiego [Belarusians and Ukrainians in the policies of the Pilsudski party] (in Polish). Wydawnictwo Uniwersyteckie Trans Humana. p. 37. ISBN 978-83-89190-87-1.

- ↑ Mironowicz, Eugeniusz (2007). Białorusini i Ukraińcy w polityce obozu piłsudczykowskiego [Belarusians and Ukrainians in the policies of the Pilsudski party] (in Polish). Wydawnictwo Uniwersyteckie Trans Humana. p. 36. ISBN 978-83-89190-87-1.

- 1 2 3 Козляков, Владимир. "В борьбе за единство белорусского народа - к 75-летию воссоединения Западной Беларуси с БССР" [In the struggle for the reunification of the Belarusian people - to the 75 anniversary of the reunification of West Belarus and the BSSR] (in Russian). Белорусский государственный технологический университет / Belarusian State Technological Institute. Retrieved 26 July 2016.

In 1939, over 90% of children in Poland attended school. — Norman Davies (2005). God's Playground. A History of Poland. II: 1795 to the Present. Oxford University Press. p. 175. ISBN 0199253390.

- ↑ Mironowicz, Eugeniusz (2007). Białorusini i Ukraińcy w polityce obozu piłsudczykowskiego [Belarusians and Ukrainians in the policies of the Pilsudski party] (in Polish). Wydawnictwo Uniwersyteckie Trans Humana. p. 33. ISBN 978-83-89190-87-1.

- 1 2 Mironowicz, Eugeniusz (2007). Białorusini i Ukraińcy w polityce obozu piłsudczykowskiego [Belarusians and Ukrainians in the policies of the Pilsudski party] (in Polish). Wydawnictwo Uniwersyteckie Trans Humana. p. 34. ISBN 978-83-89190-87-1.

- ↑ Barbara Toporska (1962). "Polityka polska wobec Białorusinów".

- ↑ Сачанка, Барыс (1991). Беларуская эміграцыя [Belarusian emigration] (PDF) (in Belarusian). Minsk.

Вось што, напрыклад, заяўляў з трыбуны сейма польскі міністр асветы Скульскі: «Запэўніваю вас, паны дэпутаты, што праз якіх-небудзь дзесяць гадоў вы са свечкай не знойдзеце ні аднаго беларуса»

- ↑ Вераніка Канюта. Класікі гавораць..., Zviazda, 21.02.2014

- ↑ Аўтапартрэт на фоне класіка, Nasha Niva, 19.08.2012

- ↑ Mironowicz, Eugeniusz (2007). Białorusini i Ukraińcy w polityce obozu piłsudczykowskiego [Belarusians and Ukrainians in the policies of the Pilsudski party] (in Polish). Wydawnictwo Uniwersyteckie Trans Humana. pp. 4, 5. ISBN 978-83-89190-87-1.

- ↑ Mironowicz, Eugeniusz (2007). Białorusini i Ukraińcy w polityce obozu piłsudczykowskiego [Belarusians and Ukrainians in the policies of the Pilsudski party] (in Polish). Wydawnictwo Uniwersyteckie Trans Humana. p. 12. ISBN 978-83-89190-87-1.

- ↑ Кореневская, О. (2003). "Особенности Западнобелорусского возрождения (на примере периодической печати)" (PDF). Białoruskie Zeszyty Historyczne (20): 69–89.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Учебные материалы » Лекции » История Беларуси » ЗАХОДНЯЯ БЕЛАРУСЬ ПАД УЛАДАЙ ПОЛЬШЧЫ (1921—1939 гг.)

- ↑ "Молодечно в периоды польских оккупаций.". Сайт города Молодечно (in Russian).

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 Hielahajeu, Alaksandar (17 September 2014). "8 мифов о "воссоединении" Западной и Восточной Беларуси" [8 Myths about the "reunification" of West Belarus and East Belarus] (in Russian). Retrieved 26 July 2016.

- ↑ Mironowicz, Eugeniusz (2007). Białorusini i Ukraińcy w polityce obozu piłsudczykowskiego [Belarusians and Ukrainians in the policies of the Pilsudski party] (in Polish). Wydawnictwo Uniwersyteckie Trans Humana. p. 45. ISBN 978-83-89190-87-1.

- ↑ Mironowicz, Eugeniusz (2007). Białorusini i Ukraińcy w polityce obozu piłsudczykowskiego [Belarusians and Ukrainians in the policies of the Pilsudski party] (in Polish). Wydawnictwo Uniwersyteckie Trans Humana. p. 72. ISBN 978-83-89190-87-1.

W najpomyślniejszym dla szkolnictw a białoruskiego roku 1928 istniało w Polsce 69 szkół w których nauczano języka białoruskiego. Wszystkie te placów ki ośw iatow e znajdow ały się w w ojew ództw ach w ileńskim i now ogródzkim, gdzie funkcjonowały 2164 szkoły polskie. Szkoły z nauczaniem języka białoruskiego, głównie utrakw istyczne, stanow iły niewiele ponad 3 procent ośrodków edukacyjnych na tym obszarze

- ↑ Mironowicz, Eugeniusz (2007). Białorusini i Ukraińcy w polityce obozu piłsudczykowskiego [Belarusians and Ukrainians in the policies of the Pilsudski party] (in Polish). Wydawnictwo Uniwersyteckie Trans Humana. pp. 41, 53, 54. ISBN 978-83-89190-87-1.

- ↑ Stosunki polsko-białoruskie. Bialorus.pl, Białystok, Poland. Retrieved from the Internet Archive on 9 September 2015.

- ↑ Mironowicz, Eugeniusz (2007). Białorusini i Ukraińcy w polityce obozu piłsudczykowskiego [Belarusians and Ukrainians in the policies of the Pilsudski party] (in Polish). Wydawnictwo Uniwersyteckie Trans Humana. p. 93. ISBN 978-83-89190-87-1.

- ↑ Andrzej Poczobut; Joanna Klimowicz (June 2011). "Białostocki ulubieniec Stalina" (PDF file, direct download 1.79 MB). Ogólnokrajowy tygodnik SZ «Związek Polaków na Białorusi» (Association of Poles of Belarus). Głos znad Niemna (Voice of the Neman weekly), Nr 7 (60). pp. 6–7 of current document. Retrieved 24 May 2014.

- ↑ Andrew Savchenko (2009). Belarus: A Perpetual Borderland. BRILL. pp. 106–107. ISBN 9004174486.

- ↑ Sanko, Zmicier; Saviercanka, Ivan (2002). 150 пытаньняў і адказаў з гісторыі Беларусі [150 Questions and Answers on the History of Belarus] (in Belarusian). Vilnius: Наша Будучыня. ISBN 985-6425-20-4.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Marek Jan Chodakiewicz, 2012, Intermarium: The Land between the Black and Baltic Seas, Transaction Publishers, pp. 81–82.

- 1 2 Prof. Bogdan Musial (January 25–26, 2011). "The 'Polish operation' of the NKVD" (PDF). The Baltic and Arctic Areas under Stalin. Ethnic Minorities in the Great Soviet Terror of 1937-38. University of Stefan Wyszyński in Warsaw. pp. 17–. Retrieved April 26, 2011.

UMEA International Research Group. Abstracts of Presentations.

- ↑ O.A. Gorlanov. "A breakdown of the chronology and the punishment, NKVD Order № 00485 (Polish operation) in Google translate". Retrieved April 26, 2011.

- ↑ Norman Davies, God's Playground (Polish edition), second tome, p.512-513

- ↑ (Polish) Stosunki polsko-białoruskie pod okupacją sowiecką (1939-1941)

- 1 2 3 Bernd Wegner (1997). From peace to war: Germany, Soviet Russia, and the world, 1939-1941. Berghahn Books. pp. 73–75. ISBN 1-57181-882-0.

- ↑ (Belarusian)Уладзімір Снапкоўскі. Беларусь у геапалітыцы і дыпламатыі перыяду Другой Сусветнай вайны

- ↑ (Belarusian) Сёньня — дзень ўзьяднаньня Заходняй і Усходняй Беларусі

- ↑ A Forgotten Odyssey 2001 Lest We Forget Productions.

- ↑ T-Styl (September 17, 2012). "Ці лічыць святам для беларусаў 17 верасня? — меркаванні жыхароў Гродна" [September 17 considered a holiday for Belarusians? Opinions of residents of Hrodna]. Твой Стыль. Retrieved 30 September 2015.

- ↑ "17 верасня: Дзень уз'яднання пад адным акупантам" [September, 17: Day of Reunification Under One Occupant]. Nasha Niva. September 17, 2014. Retrieved 19 July 2016.

Literature

- Janusz Żarnowski, "Społeczeństwo Drugiej Rzeczypospolitej 1918-1939" (in Polish language), Warszawa 1973

- Eugeniusz Mironowicz, "Białoruś" (in Polish language), Trio, Warszawa, 1999, ISBN 83-85660-82-8

- Eugeniusz Mironowicz, Białorusini i Ukraińcy w polityce obozu piłsudczykowskiego (in Polish language), Wydawnictwo Uniwersyteckie Trans Humana, Białystok, 2007, ISBN 978-83-89190-87-1

External links

- (Belarusian) Жыцьцё і сьмерць мітаў: Заходняя Беларусь