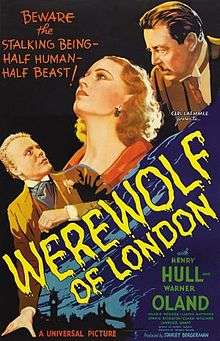

Werewolf of London

| Werewolf of London | |

|---|---|

| |

| Directed by | Stuart Walker |

| Produced by | Stanley Bergerman |

| Written by |

Robert Harris (story) John Colton |

| Starring |

Henry Hull Warner Oland Valerie Hobson Lester Matthews Spring Byington Clark Williams Lawrence Grant |

| Music by | Karl Hajos |

| Cinematography | Charles J. Stumar |

| Edited by |

Russell F. Schoengarth Milton Carruth |

Production company | |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 75 minutes |

| Language | English, Tibetan, Latin |

| Budget | $195,000[1] |

Werewolf of London is a 1935 Horror film directed by Stuart Walker, starring Henry Hull as the titular werewolf, and produced by Universal Pictures. Jack Pierce's eerie werewolf make-up was simpler than his version six years later for Lon Chaney, Jr. in The Wolf Man.

Werewolf of London was the first Hollywood mainstream werewolf movie. The film's supporting cast features Warner Oland and Valerie Hobson.

Plot

Wilfred Glendon (Henry Hull) is a wealthy and world-renowned English botanist who journeys to Tibet in search of the elusive mariphasa plant. While there, he is attacked and bitten by a creature later revealed to be a werewolf, although he succeeds in acquiring a specimen of the mariphasa. Once back home in London he is approached by a fellow botanist, Dr. Yogami (Warner Oland), who claims to have met him in Tibet while also seeking the mariphasa. Yogami warns Glendon that the bite of a werewolf would cause him to become a werewolf as well, adding that the mariphasa is a temporary antidote for the disease.

Glendon does not believe the mysterious Yogami. That is, not until he begins to experience the first pangs of lycanthropy, first when his hand grows fur beneath the rays of his moon lamp (which he is using in an effort to entice the mariphasa to bloom), and later that night during the first full moon. The first time, Glendon is able to use a blossom from the mariphasa to stop his transformation. His wife Lisa (Valerie Hobson) is away at her aunt Ettie's party with her friend, former childhood sweetheart Paul Ames (Lester Matthews), allowing the swiftly transforming Glendon to make his way unhindered to his at-home laboratory, in the hopes of acquiring the mariphasa's flowers to quell his lycanthropy a second time. Unfortunately Dr. Yogami, who is also a werewolf, sneaks into the lab ahead of his rival and steals the only two blossoms. As the third has not bloomed, Glendon is out of luck.

Driven by an instinctive desire to hunt and kill, he dons his hat and coat and ventures out into the dark city, killing an innocent girl. Burdened by remorse, Glendon begins neglecting Lisa (more so than usual), and makes numerous futile attempts to lock himself up far away from home, including renting a room at an inn. However, whenever he transforms into the werewolf he escapes and kills again. After a time, the third blossom of the mariphasa finally blooms, but much to Glendon's horror, it is stolen by Yogami, sneaking into the lab while Glendon's back is turned. Catching Yogami in the act, Glendon finally realizes that Yogami was the werewolf that attacked him in Tibet. After turning into the werewolf yet again and slaying Yogami, Glendon goes to the house in search of Lisa, for the werewolf instinctively seeks to destroy that which it loves the most.

After attacking Paul on the front lawn of Glendon Manor, but not killing him, Glendon breaks into the house and corners Lisa on the staircase and is about to move in for the kill when Paul's uncle, Col. Sir Thomas Forsythe (Lawrence Grant) of Scotland Yard, arriving with several police officers in tow, shoots Glendon once. As he lies dying at the bottom of the stairs, Glendon, still in werewolf form, speaks: first to thank Col. Forsythe for the merciful bullet, then saying goodbye to Lisa, apologizing that he could not have made her happier. Glendon then dies, reverting to his human form in death.

Cast

- Henry Hull as Dr. Glendon

- Warner Oland as Dr. Yogami

- Valerie Hobson as Lisa Glendon

- Lester Matthews as Paul Ames

- Lawrence Grant as Sir Thomas Forsythe

- Spring Byington as Miss Ettie Coombes

- Clark Williams as Hugh Renwick

- J.M. Kerrigan as Hawkins

- Charlotte Granville as Lady Forsythe

- Ethel Griffies as Mrs. Whack

- Zeffie Tilbury as Mrs. Moncaster

- Jeanne Bartlett as Daisy

Production

Sound and make-up

Jack Pierce's original werewolf design for Henry Hull was identical to the one used later for Lon Chaney, Jr. in The Wolf Man, but it was rejected in favor of a minimalist approach that was less obscuring to facial expressions. Although it has often been reported that this was because Hull was unwilling to spend hours having makeup applied,[2] or because he didn't want his face obscured because of vanity, the real reason, according to Hull's great-nephew Cortlandt Hull, who heard it from Hull himself, is that Hull—who was an accomplished makeup artist in his own right—argued that, according to the script, the werewolf had to be instantly recognizable to the other characters as Dr. Glendon. This would not have been possible under the more extreme makeup. Pierce resisted the change, so Hull went over Pierce's head to the studio head, Carl Laemmle, who approved, much to Pierce's annoyance.[3]

The werewolf's howl was an audio blend of Hull and a recording of an actual timber wolf, an approach which was never duplicated in any subsequent werewolf film. Also, at the beginning of the film, the supposed "Tibetan" spoken by villagers in the movie is actually Cantonese; Henry Hull is otherwise just muttering gibberish in his responses to them.

Reception

Frank S. Nugent, reviewing in The New York Times what was the last film to appear in the Rialto Theatre before the theatre was torn down and rebuilt in 1935, called the film a "charming bit of lycanthropy"; according to Nugent, the film was

"Designed solely to amaze and horrify, the film goes about its task with commendable thoroughness, sparing no grisly detail and springing from scene to scene with even greater ease than that oft attributed to the daring young aerialist. Granting that the central idea has been used before, the picture still rates the attention of action-and-horror enthusiasts. It is a fitting valedictory for the old Rialto, which has become melodrama's citadel among Times Square's picture houses.[4]

Film critic Leonard Maltin awarded the film 2 1/2 out of a possible 4 stars, calling the film "dated but still effective", complimenting Oland's performance as Dr. Yogami.[5] The movie was considered at the time as too similar to Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (1931) with Fredric March, which had been released only a few years before, and flopped at the box-office.

Legacy

The film inspired at least four pop culture entries: Warren Zevon's 1978 hit song "Werewolves of London"; the 1981 film An American Werewolf in London, the 1997 sequel An American Werewolf in Paris and the 1987 video game Werewolves of London.

The story has been novelized twice. The first time was in 1977, a paperback novel written under the pseudonym "Carl Dreadstone" (now confirmed as Walter Harris) [6] as part of a short-lived series of books based on the classic Universal horror films. The novel is told from the point of view of Wilfred Glendon (whose first name is now inexplicably spelled "Wilfrid") and thus follows an almost entirely different story structure than the film. In particular it has a different ending. Rather than turning into a werewolf, killing Yogami, and then being shot by Sir Thomas, Glendon decides to cooperate with Yogami and they both attempt to control their transformations through hypnotism. However the plan fails, the hypnotist is killed, and Glendon and Yogami both transform and fight to the death. Glendon wins, killing Yogami, and returns to human form afterwards. The novel then ends with Glendon, alive, contemplating using the hypnotist's gun to commit suicide rather than go on living as a werewolf.

The second time was in 1985, as part of Crestwood House's hardcover Movie Monsters series, again based on the old Universal films. This time, the author was Carl Green, and was considerably shorter, followed the plot of the film more closely, and was illustrated extensively with still photos from the movie.

See also

References

- ↑ Michael Brunas, John Brunas & Tom Weaver, Universal Horrors: The Studios Classic Films, 1931-46, McFarland, 1990 p131

- ↑ Clarens, Carlos (1968). Horror Movies: An illustrated Survey. London: Panther Books. pp. 119–20.

- ↑ "HENRY HULL & JOSEPHINE HulL IT'S IN THE BLOOD!". line feed character in

|title=at position 28 (help) - ↑ Nugent, Frank S. (May 10, 1935). "Werewolf of London (1935), at the Rialto". The New York Times. Retrieved September 7, 2014.

- ↑ Leonard Maltin; Spencer Green; Rob Edelman (January 2010). Leonard Maltin's Classic Movie Guide. Plume. p. 736. ISBN 978-0-452-29577-3.

- ↑ Ian Covell "Ian Covell on ‘Carl Dreadstone’", Souvenirs Of Terror fiendish film & TV show tie-ins, October 3, 2007, accessed 11 July 2011.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Werewolf of London |