Water supply and sanitation in Burkina Faso

This article was written in 2010.

| Burkina Faso: Water and Sanitation | ||

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Data | ||

| Access to an improved water source | 76% (2008) [1] | |

| Access to improved sanitation | 11% (2008) [1] | |

| Continuity of supply (%) | Mostly continuous | |

| Average urban water use (liter/capita/day) | not available | |

| Average urban water tariff (US$/m3) | 0.87 (2009) [2] | |

| Share of household metering | high | |

| Annual investment in water supply and sanitation | US$17.3m (2007), or US$1.4/capita/year [2] | |

| Sources of financing | Mainly external donors | |

| Institutions | ||

| Decentralization | In some small towns and in rural areas | |

| National water and sanitation company | Yes, ONEA | |

| Water and sanitation regulator | None | |

| Responsibility for policy setting | Ministry of Water, Hydraulic Planning and Sanitation, | |

| Sector law | 2001 Water Management Act | |

| Number of urban service providers | 1 | |

| Number of rural service providers | n/a | |

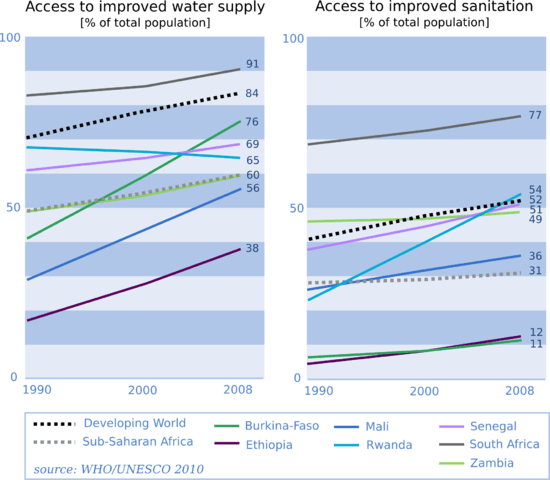

Water supply and sanitation in Burkina Faso are characterized by high access to water supply in urban areas, while access to improved water sources in rural areas - where three quarters of the population live - remains relatively low. An estimated one third of water facilities in rural areas are out of service because of a lack of maintenance. Access to improved sanitation lags significantly behind access to water supply.

The government and donor agencies alike consider urban water supply in Burkina Faso one of the rare development success stories in Sub-Saharan Africa. Access to an improved water source in urban areas increased from 73% in 1990 to 95% in 2008. Water supply that used to be intermittent now is continuous. The national utility Office National de l’Eau et de l’Assainissement (ONEA) was insolvent twenty years ago and provided poor service to a small number of customers. As of 2010, it has grown substantially and is financially healthy. The World Bank and USAID today consider the public company one of the best performing water utilities in Sub-Saharan Africa. Increasing cost recovery and improving the efficiency of service provision have been important elements in the turnaround of the utility. In the late 1990s, the World Bank had insisted that the private sector should play a significant role in providing water services in Burkina Faso. The government rejected this approach. Instead, it pragmatically integrated certain principles of market-oriented sector reforms into its own policies in order to further increase the performance of the public utility.

In rural areas, a 2004 decentralization law has given responsibility for water supply to the country's 301 municipalities (communes) which have no track record in providing or contracting out these services. Implementation of the decentralization has been slow. Municipalities, whose capacities are being strengthened, are contracting out service provision to local private companies, or in some cases to ONEA.

The government has adopted a National Sanitation Strategy in 2008 and President Blaise Compaoré launched a campaign in 2010 to boost the implementation of the strategy.

Gudinva Saloh is Burkina Faso's current Minister of Sanitation, having been appointed to this position in February 2016 by President Roch Marc Christian Kaboré.

Access

Methodologies and data sources. The Joint Monitoring Program for Water Supply and Sanitation (JMP) of WHO and UNICEF, which is the internationally accepted source for the measurement to attain the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) for water supply and sanitation, relies on the compilation of various surveys (Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS), Multiple Cluster Indicators Surveys (MCIS)) to establish access rates. These surveys typically assess the availability of infrastructure, not service quality. The 2008 estimates for Burkina Faso thus indicate access rates to an improved water source of 95 percent in urban areas and 72 percent in rural areas.[3] The Government relies on an entirely different approach, based on the concept of "reasonable access". This concept differs from the JMP approach by taking into account aspects of service quality, such as waiting time and water quality. According to the government approach, the water access rates in 2005 were lower than under the JMP approach, standing at 74 percent in urban areas and 60 percent in rural areas.[2] While the “reasonable access” approach is more sophisticated, it also faces greater challenges in terms of availability of data.

Water supply. According to JMP estimates access to an improved water source in urban areas increased from 73% in 1990 to 95% in 2008. In rural areas access doubled from 36% in 1990 to 72% in 2008.[3] The increase of access to water supply in urban areas was facilitated by the introduction of a social connection program that reduced connection fees in 2005 (see below under tariffs). However, some of the newly installed connections are not used, either because the connected compound was still waiting for actual occupancy or because households were unable to pay the monthly water bills because their income was either too low or too irregular. The share of “inactive connections” was 20% in Bobo Diolassou and 7% in Ouagadougou.

Sanitation. Sanitation in Burkina Faso is mostly in the form of on-site sanitation, including latrines for defecation and soakaway pits for greywater from showers and washing facilities. Compared to the significant increase in access to water supply, access to adequate sanitation increased only slightly between 1990 and 2008 from 28% to 33% in urban areas and from 2% to 6% in rural areas. Open defecation remains widespread, estimated at 8% in urban areas and 77% in rural areas. Those who have neither access to adequate sanitation nor defecate in the open use shared or unimproved latrines. These are not considered adequate sanitation facilities by the WHO.[4] Burkina Faso fully subsidizes the capital costs for latrines in rural areas. Despite this effort, between 2000 and 2008 the number of people defecating in the open in rural areas increased.[5]

ONEA has substantially invested in sanitation by helping households to build such shower and washing facilities connected to soakaway pits, as well as improved latrines. ONEA subsidizes these facilities with the support of international donors and with the cash generated by the sanitation surcharge on water bills. The grants provided by ONEA amount on average to 40 percent of the cost of facilities, thus making them affordable to households. Sewerage plays a marginal role in Burkina Faso. There are only 235 connections to sewers in the entire country, all in Ouagadougou.[2]

Service quality

In urban areas, water supply is mostly continuous. In Ougadougou this constitutes a significant improvement from the times before the construction of the Ziga dam and the efficiency improvements of the national water utility when supply was intermittent.

In rural areas, most residents fetch water from open wells or hand pumps. As in other African countries, the sustainability of hand pumps and other water supply systems is an issue. There are conflicting data about the share of water systems in rural areas that are out of service in Burkina Faso. According to data quoted by UNICEF, 23% of pumps in rural areas are out of service because of a lack of maintenance.[6] According to data quoted by the World Bank, of the more than 50,000 water points in rural areas 33,000 (8,000 “modern wells” and 25,000 boreholes equipped with handpumps) are functioning, i.e. more than one third of wells are out of service. Of 570 small piped systems in rural areas, 400 are functioning, i.e. also almost one third are not functioning.[2]

Water resources, water use and infrastructure

National overview of water resources. Water resources are scarce in Burkina Faso. Water availability varies greatly between regions and seasons, as well as from year to year. In the South, average rainfall is as high as 1,200mm during a six-month wet season, while in the North the wet season lasts only three months and rainfall is only 300mm.[7] The only rivers in the country that carry water all year around are the Mouhoun River (Black Volta) and the Nakambe River (White Volta), the other rivers carrying water only during the wet season. Building dams has been the most common way of storing water for the dry season, even though evaporation can reach 2,000 mm/year thus causing substantial water losses from open reservoirs. A substantial portion of surface water resources is shared with neighboring countries. For example, the Nakambe River - the main source of supply for the capital, Ouagadougou - and the Mouhoun River are shared with Ghana.[2] Surface water resources vary between 8 billion cubic meters (BCM)/year in an average year and 4 BCM in a dry year.[7] The lower figure corresponds to less than 300 cubic meters per capita and year, which is well below the level of 1,000 cubic meters per capita and year that is considered the threshold for “water stress”.

Groundwater is unevenly distributed and can only be extracted in certain areas, specifically in weathered areas above the bedrock and fractured zones. Even there yields are limited to about 10 m3/day per borehole, which is barely enough to supply a small village with water.[2]

Water use. Water use in 2000 was 0.7 BCM or less than 10% of surface water resources in an average year and less than 20% in a dry year. Only about 0.1 BCM, or slightly more than 1% of total water resources, are used for domestic water supply. Irrigation and livestock watering are the main water uses. [8]

Ougadougou water supply infrastructure. With its more than 1.2 million inhabitants the capital Ougadougou is by far the largest city in Burkina Faso. It is supplied mostly by surface water from five reservoirs:

- The "hill dams" Ouaga 1, 2 and 3 located within the city and forming Lake Ouagadougou,

- the Lumbila reservoir (36 million m3 storage) on the Massili river, about 10 km away and completed in 1947, and

- the Ziga reservoir (200 million m3 storage) which is about 50 km away and that started providing water to the capital in 2004, supplying about 70% of its needs in 2008.

The catchment area of the "hill dams" is today completely built up with settlements that have inadequate sanitation systems. Furthermore, rubbish is washed into the reservoirs during the rainy season. Furthermore, over the years, the hill dam reservoirs and the Lumbila reservoir have been gradually filled with mud and sediment. Water from the hill dams and the Lumbila reservoir is treated in the Paspanga water treatment plant, which supplied about 20-25% of the water needs of the city in 2008. Groundwater provides for about 5-10% of the water needs of the city.[9][10][11]

Ouagadougou sanitation infrastructure. Most of the population of Ouagadougou uses latrines. Only about 5% use septic tanks and an even smaller proportion is connected to a 43 km-sewer network completed in 2006 in the city center and that serves mainly commercial, industrial and institutional clients. The network discharges to a 20-ha stabilization pond in the Kossodo industrial area, which also treats sludge from septic tanks brought in by tankers.[12]

History and recent events

Creation of a national water utility (1977-1990)

Until 1977 water services were provided by a private operator, which focused on a few rich neighborhoods of the capital, Ouagadougou. Its contract was terminated in 1977.[13] In the same year the national water company ONE, whose name was changed to Office National de l’Eau et de l’Assainissement (ONEA) in 1985, took over responsibility for urban water supply in the country.[14] During its first years of existence, which were marked by a period of political instability, the utility achieved little in terms of expanding access and improving service quality.

Strengthening of the national water company ONEA during the 1990s

In the early 1990s the government initiated a process of restructuring and strengthening the national water utility ONEA, while investing heavily in expanding access with the assistance of foreign aid. Through this process the utility was transformed into one of the most successful and efficient water companies in Sub-Saharan Africa. Improving cost recovery was an important element of this process: Tariffs were increased by 30% to almost €1 per cubic meter, so that ONEA enjoyed a healthy financial situation and reported an accounting profit.[13] Increasing efficiency was another important element: Nonrevenue water declined to 16 percent, an excellent level by regional standards. Labor productivity was increased by reducing the number of employees from 670 in 1991 to 570 in 1995 while the number of customers increased substantially.[14] Furthermore, business procedures were modernized through a computerized customer billing system, customer relations were improved, an internal control system to fight corruption was introduced and a laboratory was established. The mutual responsibilities of the public company and the government were laid out in the form of a Contrat Plan setting quantitative targets over a number of years, as it is common for state-owned enterprises in many Francophone countries.[14]

Despite these successes of the public company, the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank insisted about establishing a public-private partnership for water supply in Burkina Faso during the late 1990s. A 10-year lease contract with a private French company signed previously in Senegal was cited as one positive example. Nevertheless, the government rejected the option of a lease contract, which was considered too far-reaching without completely rejecting all the elements of the sector reforms initiated in some of the neighboring West African countries. The government thus adopted only those aspects that it considered a good fit for the conditions of Burkina Faso. In that vein the government initiated sector reforms in 2001 to achieve what it called “a genuine public-public partnership between the Government and ONEA.”

An important element of the urban sector reform was that the government refrained from political interference and established tools to objectively and independently monitor the performance of ONEA. In the crucial field of cost recovery, a financial model of ONEA was developed in a participatory manner and applied, allowing the government to assess progress towards financial equilibrium of ONEA and providing an objective basis for further tariff revision requests. The government then approved requests for tariff increases submitted by the utility and justified by the outcome of the model’s calculations in a timely fashion, which was crucial to maintain the utility in good financial health. The Government also helped to strengthen the utility by not interfering with investment and staffing decisions and paying its water bills on time.[2]

Another element of the reform was that, unlike previously and unlike in many other countries with public-public performance contracts, the existing three-year Contrats Plans between the Government and ONEA were now subjected to periodic independent assessments.[2]

Private sector support to further strengthen the public utility (2001-2006)

Another element of the urban sector reform was the decision to improve commercial practices of ONEA through a short-term performance-based service contract with a private company. The international bid for this five-year service contract was won by the French private operator Veolia in January 2001, two months before the World Bank’s announcement of a new US$70 million credit for water supply in Ouagadougou. The contract covered the management of customer service and bill collections on behalf of ONEA, but kept the technical operation of the system and the supervision of the contract in the hands of the public utility. The expatriates worked as deputies to local managers and the international operator had mostly an advisory role. Yet because of the performance-based nature of the contract, it also had a clear financial stake in the success of the technical assistance provided. According to a World Bank study, “the staff sent by the international operator proved to be seasoned professionals with many years of hands-on operational experience.” With their help ONEA’s commercial performance further improved, although this took some time. The collection ratio decreased during the first two years and improved only afterward, slightly increasing beyond the pre contract performance in year three, reaching 93 percent in year four and 95 percent in year five.[13] In December 2008 ONEA became the first public water utility in Sub-Saharan Africa to be IS0 9001-certified. The World Bank today considers ONEA “a mature corporation, similar in all respects to a private corporation.”[2]

Expansion of access and the Ziga dam (2000s)

In July 2004 the President of Burkina Faso inaugurated the treatment plant and pipeline that provided water from the new Ziga dam and allowed ONEA to limit water rationing in Ouagadougou.[15][16] The dam and associated investments allowed a significant increase in water connections in Ougadougou, with the number of house connections more than tripling between 2001 and 2007.[17]

Decentralization in rural areas since 2004

Concerning rural water supply, in 2004 the government established a policy of decentralization, foreseeing to transfer the responsibility for operating and maintaining rural water systems from the state to local communities. Implementation has initially been slow, but picked up over time. In March 2009 a decree transferred the ownership of piped systems in small towns outside the ONEA service area to municipalities, which in turn contract out operation and maintenance to local private operators or to ONEA.[18] According to the World Bank, before decentralization the development of rural services suffered from an overly centralized planning and investment process, which bypassed local governments. Rural water supply was, and to some extent still is, characterized by a diversity of project rules, implementation approaches, and technical options that are left to the discretion of financing agencies and NGOs.[2]

Responsibilities for water supply and sanitation

Policy and regulation

Government policies for water supply and sanitation are codified in two main laws and in a number of national plans and strategies for specific sub-sectors. The two main laws are the 2001 Water Management Act, which formulates principles for the integrated management of water resources and for the development of the various water uses, and the 2004 Decentralization Law (Charge Générale des Collectivités Territoriales, CGCT), which sets the responsibilities for the delivery of basic services, including water supply and sanitation.[2]

Concerning national plans and strategies, in the field of integrated water resources management Burkina Faso adopted an action plan (Plan d’Action pour la Gestion Intégrale des Ressources en Eau, PAGIRE) in 2003 which emphasized gradual decentralization, in the same vein as the decentralization law.[19]

In 2006 the government adopted a National Water Supply and Sanitation Program (PN-AEPA) to achieve the Millennium Development Goals. In 2008 the government also adopted a Rural Water Supply Maintenance Reform Paper. Also in 2008 the government adopted an updated Sanitation Strategy.[2] To support the strategy, the President of Burkina Faso launched a national campaign to increase access to adequate sanitation in June 2010.[20]

_(2957048773).jpg)

Within the government, the Ministry of Agriculture, Water and Fisheries is responsible for setting national policies for water supply. Within the Ministry the General Directorate for Water Resources (Direction Générale des Ressources en Eau, DGRE) is responsible for water resources management and the General Directorate of Drinking Water Supply (Direction Générale de l’Approvisionnement en Eau Potable, DGAEP) is in charge of drinking water supply.

Service provision

Urban areas. Burkina Faso’s urban water and sanitation service provider is the national utility Office National de l’Eau et de l’Assainissement (ONEA). According to the World Bank and USAID, ONEA has an excellent record of performance in West Africa.[13][19] It serves 43 cities and towns throughout the country. ONEA’s and the government’s mutual responsibilities are laid out in three-year performance contracts (contracts plans) with explicit operational targets. A board of directors is responsible for the supervision of ONEA’s performance and for all strategic decisions. It has the authority to appoint (and fire) the general manager and determine employees’ pay scales, while a general manager makes day-to-day operational decisions. The utility is allowed to cut off service for nonpayment of water bills, and its workers are subject to private sector (not civil service) rules.[13]

The urban centers served by ONEA have an estimated population of 3.3 million people in 2008, about one quarter of the country's population. The two largest cities, Ouagadougou and Bobo-Dioulasso, account for 64 percent of the total population served by the utility.[2] A sanitation department (Direction de l'assainissement, DASS) is specifically responsible for urban sanitation.

Rural areas. In rural areas and small towns outside the service area of ONEA, where about three quarters of the population live, community service providers (Associations d'usagers de l'eau) have relied upon support from international donors and local and international non-governmental organizations (NGO).[19] The decentralization process initiated in 2004 led to a transfer of the responsibility for water supply and sanitation to the municipalities (communes) in 2009, but confirmed the mandate of ONEA to deliver urban and sanitation services within its existing service area. As mentioned above, the municipalities are not expected to deliver services themselves, but rather to delegate the delivery to public entities such as ONEA or local private companies.[2] In some regions community service providers have associated themselves at the regional level. One example is the Fédération des usagers de l'eau de la région de Bobo-Dioulasso (Faureb). The members of the federation set a unique water tariff for the 40 small towns and villages in their region. They also administer funds for maintenance, renewal and new investments through the Federation's management center (Centre de gestion). This mechanisms also allows for cross-subsidies between the different small towns and villages in the Federation.[18]

Water resources management

At the local level, water committees (Comités Locaux de l'Eau, CLE) are in the process to be established to carry out Integrated Water Resources Management (IWRM). As a first step the committees are expected to elaborate water management plans (Schemas Directeurs de la Gestion de l’Eau, SAGE).

Other responsibilities

There is also a water and sanitation NGO network and a water and sanitation journalists network.[21]

Efficiency

Concerning ONEA, at 18% non-revenue water is one of the lowest in Sub-Saharan Africa. Labor productivity is average with 4.3 employees per 1,000 connections, calculated based on 775 employees and 182,000 connections in 2010.[22]

Financial aspects

Investments. In 2007, the estimated cost to meet the MDG goals for access to improved drinking water and sanitation facilities required an annual investment of $78 million for water and $28 million for sanitation. By comparison, the 2007 public budget for WSS sector improvements amounted to only $13.3 million for water and $4 million for sanitation.[19] According to the PN-AEPA, to achieve its goals, total financing of US324 million ($43 million per year) is required between 2007 and 2015 in urban areas and US$810 million (US$ 101m per year) in rural areas.[2] There are sufficient donor commitments to achieve the goals in urban areas, while there is a funding gap in rural areas.

Tariffs. Tariffs are identical for the entire service area of ONEA, with the objective of cross subsidies between localities. The ONEA water tariffs are among the highest in Sub-Saharan Africa, reaching on average CFA franc 440/m3 (US$0.87/m3). The tariff structure is based on an increasing block rate system, with a social block including a basic consumption of 8 cubic meter per household and month at CFAF 209/m3 (US$0.41/m3) including the sanitation surcharge. However, taking into account the fixed monthly fee of CFAF 1,000 (US$2), a household consuming 6 m3 per month actually pays the equivalent of CFAF 375/m3 (US$0.75/m3). Commercial users, public buildings and residential users with a consumption of more than 30m3/month pay CFAF 1,040 per m3 (US$ 2.05/m3).[2] Consumers using standpipes should pay CFAF 5 (US$0.01) for a 20-liter bucket, CFAF 10 (US$0.02) for a 40-liter bucket and CFAF 60 (US$0.12) for a 220-liter barrel. The price per bucket corresponds to CFAF 250/m3 (US$0.50/m3). However, this official rate is not well enforced and in practice users pay between CFAF 350 and 600/m3 (US$0.75/m3 - US$1.20/m3).[2] Standpipe caretakers pay CFAF 188/m3 (US$0.37/m3) to the utility and earn a living based on the margin they charge. Consumers using vendors pay much higher rates, around CFAF 1,000-1,500/m3 (US$2–3/m3).[2] Under a social connection program, connection fees charged by the national utility for household connections, which were set at CFAF 120,000 (US$240) in 2005, corresponding to the full cost of establishing the connection, were first reduced to CFAF 50,000 (US$lOO) and then to CFAF 30,000 (US$60) [2]

Tariffs in rural areas, where they exist, are set at the local level and differ from one locality to the other. In the Hauts-Bassins Region and Cascades Region, a Federation of water user groups has set the tariff in rural areas at CFAF 500/m3 (US$1/m3). 40% of this amount is supposed to be used for operating costs at the village level and 60% is paid into funds for maintenance, renewal and new investments as well as for a support unit at the regional level. The water tariff for rural areas in this part of the country thus is higher than the national urban water tariff for residential users charged by ONEA.[18]

Affordability. According to a water tariff study by ICEN and Sogreah carried out in 2007 the average ONEA residential water bill was 4,400 CFAF (US$ 8.80) per month for a household connection using 45 liter per capita and day, corresponding to about 4% of household income. It was estimated that households that fetched water from standpipes paid 2,600 CFAF (US$ 5.20) or 3% of their income to receive 28 liter per capita and day.[2]

External cooperation

A joint aid strategy for Burkina Faso is expected in 2009 following in the footsteps of a “Plan d’Action National de l’Efficacité de l’Aide” (PANEA).[19] Among the main external partners in the water and sanitation sector in Burkina Faso are the African Development Bank, the Arab Bank for Economic Development in Africa, Denmark, the Kuwait Fund for Arab and Economic Development, the European Investment Bank, the European Union, France, Germany, the Islamic Development Bank, the OPEC Fund for International Development, the West African Development Bank and the World Bank. The donors increasingly finance projects together in the spirit of the Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness, thus reducing the fragmentation of external cooperation. In addition to public donor agencies, many NGOs are active in water and sanitation in Burkina Faso.

Public partners

Projects jointly funded by multiple donors. The US$270m Ouagadougou Water Supply Project (2001–2007), which secured the water supply of the capital through the Ziga dam and associated infrastructure, was supported by 11 donors convened by the World Bank.[17]

Germany. German development cooperation supports water and sanitation projects and programs implemented by ONEA as well as the decentralized directorates of the ministries and regional authorities. It supported the improvement and expansion of the water supply of Bobo-Dioulasso as well as the collection and treatment of industrial and household sewage in the same city. Together with 13 other donors, Germany was also involved in the construction of the Ziga dam which ensures a continuous water supply for the population of Ouagadougou and the population living around the reservoir. Another German project promotes water supply in Fada N’Gourma. German cooperation also supports the construction and rehabilitation of tube wells in rural areas in the Boucle du Mouhoun province and in five provinces of the Eastern Region. Germany also supports the provision of water supply and sanitation for households, schools and hospitals in small and medium towns in the country’s southwest.[23]

UNICEF. UNICEF is particularly active in school water supply and sanitation, as well as in hygiene education through schools. It has helped to provide schools with 170 wells and rehabilitate 50 water pumps. This has contributed to reducing the prevalence of guinea worm infection from 1,956 cases in 2000 to 30 cases in 2005 and also to increasing water access in schools from 39% to 82% over the same period. Sanitation and hygiene education was intensified, using primary schools as an entry point: 139 schools were equipped with special latrines, teacher and students were trained in hygiene education, and children participated in activities targeting behavior change in families.[6]

Non-governmental organizations

WaterAid. Following a pilot project that began in 2001 WaterAid began developing partnerships and programmes in the rural Garango, Ramongo and Bokin districts. In 2003 work extended to include Bogodogo and Sigh-Noghin districts in Ouagadougou. WaterAid now works with seven partner organisations. According to its website, it helped over 32,000 people gain access to clean water and started a credit scheme for sanitation and soap-making enterprises with women.[21]

Initiative: Eau. Initiative: Eau is an NGO committed to providing sustainable support to regions experiencing lack of access to clean water, and a need for improved sanitation by promoting community-led initiatives and by engaging in innovative research. The organization currently operates in the greater Ouagadougou and Fada N'gourma regions, engaging both in water and sanitation supply and infrastructure surveillance. Through WASHMobile, its program to collect and disseminate water quality information to reduce water-borne illness rates, it has monitored water quality for over 15 000 individuals in its pilot phase.[24]

See also

External links

References

- 1 2 Joint Monitoring Program for Water Supply and Sanitation:Data tables, accessed on August 19, 2010 Archived March 23, 2010, at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 World Bank:Burkina Faso - Urban Water Sector Project, Project Appraisal Document, Annex 1:Country and Sector Background, 30 April 2009, accessed on August 10, 2010

- 1 2 3 Joint Monitoring Program for Water Supply and Sanitation (JMP): Burkina Faso: improved water coverage estimates, 1980-2010, accessed on August 10, 2010

- ↑ Joint Monitoring Program for Water Supply and Sanitation (JMP): Burkina Faso: improved sanitation coverage estimates, 1980-2010, accessed on August 10, 2010

- ↑ EU Water Initiative Africa (April 2011). "Update on EU Aid to Water and Sanitation in Africa Political Briefing Note EU Water Initiative Africa Working Group" (PDF). p. 5. Retrieved 23 October 2011.

- 1 2 UNICEF: Water, Environment and Health: Burkina Faso, accessed on August 9, 2010

- 1 2 FAO: Aquastat Country Profile, Version 2005, accessed on August 10, 2010

- ↑ FAO: Aquastat Burkina Faso, 2005, accessed on August 9, 2010

- ↑ UN Habitat: Water for African Cities:Burkina Faso, accessed on August 9, 2010

- ↑ (French) P. Cecchi, Institut de Recherche pour le développement (IRD):L’alimentation en eau de la ville de Ouagadougou, ca. 2003, accessed on August 19, 2010

- ↑ Lefaso.net:La station de traitement d’eau de Paspanga retrouve 40% de son efficacité, 11 September 2009, accessed on August 19, 2010

- ↑ "Projet d'assainissement collectif de la ville de Ouagadougou, Série Evaluation et Capitalisation n° 16, July 2008". Agence française de développement.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Corporatizing a water utility. A successful case using a performance-based service contract for ONEA in Burkina Faso, Gridlines, Note 53, March 2010" (PDF). Public-Private Infrastructure Advisory Facility (PPIAF). Retrieved August 9, 2010.

- 1 2 3 (French) ONEA: Léntreprise: bref historique, accessed on August 9, 2010

- ↑ IRIN: BURKINA FASO: Water shortage becomes more accute in capital, 22 May 2003

- ↑ (French) LeFaso.net Barrage de Ziga : L’eau jaillit à Ouagadougou, 12 July 2004

- 1 2 World Bank:Turning the Water On in Burkina’s Capital City, August 2009

- 1 2 3 (French) Alicia Tsitsikalis (Gret):Pour une gestion partagée de l'eau entre associations d'usagers, La lettre du pS-Eau No. 62, June 2010

- 1 2 3 4 5 USAID: Burkina Faso Water and Sanitation Profile, ca. 2008

- ↑ (French) allAfrica.com:Burkina Faso: Accès à un assainissement adéquat - Une priorité nationale, 30 June 2010

- 1 2 WaterAid: Burkina Faso, accessed on July 29, 2010

- ↑ ONEA. "L'ONEA en chiffres". Retrieved 2 December 2012.

- ↑ GTZ: Drinking Water and Sanitation Programme in Small and Medium-Sized Towns

- ↑ Initiative: Eau: . accessed on October 13, 2016