Washingtonia filifera

| Washingtonia filifera | |

|---|---|

| |

| Washingtonia filifera in native grove near Twentynine Palms, California. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| (unranked): | Angiosperms |

| (unranked): | Monocots |

| (unranked): | Commelinids |

| Order: | Arecales |

| Family: | Arecaceae[1] |

| Genus: | Washingtonia |

| Species: | W. filifera |

| Binomial name | |

| Washingtonia filifera (Lindl.) H.Wendl. | |

| |

| Natural range | |

| Synonyms[2][3] | |

| |

Washingtonia filifera, also known as desert fan palm[4] or California fan palm or California palm,[5][6][7] is a flowering plant in the palm family (Arecaceae), and native to the southwestern U.S. and Baja California. Growing to 15–20 m (49–66 ft) tall by 3–6 m (10–20 ft) broad, it is an evergreen monocot with a tree-like growth habit. It has a sturdy columnar trunk and waxy fan-shaped (palmate) leaves.

Names

Other common names include California fan palm and petticoat palm. The specific epithet filifera means "thread-bearing".

Distribution

Washingtonia filifera is the only palm native to the Western United States and the country's largest native palm.[8][9]

Primary populations are found in desert riparian habitats at spring-fed and stream-fed oases in the Colorado Desert[10] and at a few scattered locations in the Mojave Desert.[11] It is also found near watercourses in the Sonoran Desert along the Gila River in Yuma,[12] along the Hassayampa River and near New River in Maricopa County, and in portions of Pima County, Pinal County, Mohave County (along the Colorado River) and several other isolated locations in Clark County, Nevada. It is a naturalized species in the warm springs near Death Valley and in the extreme northwest of Sonora (Mexico). It is also reportedly naturalized in the Southeast, Florida, Hawaii, the U.S. Virgin Islands, and Australia (New South Wales).[13][14]

Description

Washingtonia filifera grows to 18 metres (59 ft) in height (occasionally to 25 metres (82 ft)) in ideal conditions. The California Fan Palm Tree is also known as the Desert Fan Palm, American Cotton Palm and Arizona Fan Palm.

The fronds are up to 3.5–4 metres (11–13 ft) long, made up of a petiole up to 2 metres (6.6 ft) long, bearing a fan of leaflets 1.5–2 metres (4.9–6.6 ft) long. They have long thread-like white fibers and the petioles are pure green with yellow edges and filifera-filaments, between the segments. The trunk is gray and tan and the leaves are gray green. When the fronds die they remain attached and drop down to cloak the trunk in a wide skirt. The shelter that the skirt creates provides a microhabitat for many small birds and invertebrates. If there is any red color present on petioles or trunk it is not a pure filifera but a fila-busta hybrid.

Washingtonia filifera can live from 80 to 250 years or more.

Ecology

Desert fan palms provide habitat for the giant palm boring beetle, western yellow bat, hooded oriole and many other bird species. Hooded orioles rely on the trees for food and places to build nests. Numerous insect species visit the hanging inflorescences that appear in late spring.[15]

Threats

The palm boring beetle Dinapate wrightii (Bostrichidae) can chew through the trunks of this as well as other palms. Eventually a continued infestation of beetles can kill various genera and species of palms. The recent discovery of the red palm weevil (Rhynchophorus ferrugineus) in Southern California may pose a threat to many palms, with coastal garden W. filifera specimens already a known host.[16] However, it seems that this species is resistant to the red palm weevil through a mechanism based on antibiosis.[17][18]

Currently the desert fan palm is experiencing a population and range expansion, perhaps due to global warming.[19]

History

Historically, natural oases are mainly restricted to areas downstream from the source of hot springs, though water is not always visible at the surface.

Grazing animals can kill young plants through trampling, or by eating the terminus at the apical meristem, the growing portion of the plant. This may have kept palms restricted to a lesser range than indicated by the availability of water.

Today's oasis environment may have been protected from colder climatic changes over the course of its evolution. Thus this palm is restricted by both water and climate to widely separated relict groves. The trees in these groves show little if any genetic differentiation, (through electrophoretic examination) suggesting that the genus is genetically very stable.

Access

Joshua Tree National Park in the Mojave Desert preserves and protects healthy riparian palm habitat examples in the Little San Bernardino Mountains, and westward where water rises through the San Andreas Fault on the east valley side. In the central Coachella Valley the Indio Hills Palms State Reserve and nearby Coachella Valley Preserve, other large oases are protected and accessible. The Santa Rosa and San Jacinto Mountains National Monument, and Anza-Borrego Desert State Park both have large and diverse W. filifera canyon oasis habitats.

Native Americans

The fruit of the fan palm was eaten raw, cooked, or ground into flour for cakes.[20] The Cahuilla and related tribes used the leaves to make sandals, thatch roofs, and baskets. The stems were used to make cooking utensils. The Moapa band of Paiutes as well as other Southern Paiutes have written memories of using this palm's seed, fruit or leaves for various purposes including starvation food.[21][22]

Cultivation

Washingtonia filifera is widely cultivated as an ornamental tree. It is one of the hardiest Coryphoidiae palms, rated as hardy to USDA hardiness zone 8. It will survive brief temperatures of −10 °C (14 °F) with minor damage, and established plants have survived, with severe leaf damage, brief periods as low as −12 °C (10 °F). The plants grow best in Mediterranean climates, but can be found in humid subtropical climates like eastern Australia and the southeastern USA.

Washingtonia filifera has gained the Royal Horticultural Society's Award of Garden Merit.[23]

References

- ↑ Uhl, Natalie W.; Harold E Moore; John Dransfield (1987). Genera Palmarum: a classification of palms based on the work of Harold E. Moore, Jr. Lawrence, Kansas: L.H. Bailey Hortorium: International Palm Society. ISBN 9780935868302. OCLC 15641317.

- ↑ "Washingtonia filifera (Linden ex André) H. Wendl. ex de Bary". Tropicos.org. Missouri Botanical Garden. Retrieved 20 June 2014.

- ↑ "Washingtonia filifera (Linden ex André) H.Wendl. ex de Bary". PlantList. 2013. Retrieved 20 June 2014.

- ↑ Cornett, J. W. (1986). "The Common Name of Washingtonia filifera". Principes. 30 (4): 153–155.

- ↑ Griffin, Bruce (2000). A Natural History of the Sonoran Desert. University of California Press. Page 165. ISBN 9780520219809.

- ↑ Kearney, Thomas and Robert Hibbs Peebles (1960). Arizona Flora. University of California Press. Page 164. ISBN 9780520006379.

- ↑ Flora of North America Association. Flora of North America: North of Mexico Volume 22: Magnoliophyta: Alismatidae, Arecidae, Commelinidae(in Part), and Zingiberidae. Page 106. ISBN 9780195137293.

- ↑ Hogan, C. Michael (2009-01-05). "California Fan Palm (Washingtonia filifera)". iGoTerra. Retrieved 20 June 2014.

- ↑ Clover, E.U. (April 1937). "Vegetational survey of the lower Rio Grand Valley, Texas". Madroño. 4 (2): 41–66. JSTOR 41422215.

- ↑ Cornett, James W. (1997). The Sonoran Desert: A Brief Natural History. Palm Springs, California: Palm Springs Desert Museum. ISBN 0-937794-27-9.

- ↑ Cornett, James W. (1987). Naturalized Populations of the Desert Fan Palm, Washingtonia filifera, in Death Valley National Monument in Plant Biology of Eastern California. Los Angeles, California: White Mountain Research Station, University of California, Los Angeles. pp. 167–174.

- ↑ Mark Nothaft (March 22, 2016). "Are palm trees native to Arizona?". Retrieved March 26, 2016.

Mark Fleming, curator of botany at the Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum of Tucson, says Washingtonia filifera, or the California fan palm, is the state's only naturally occurring variety and that they are found in pockets around southern California, Northern Mexico and one or two pockets in Arizona.

- ↑ "Plant Profile for Washingtonia filifera (California fan palm)". Natural Resources Conservation Service. United States Department of Agriculture. Retrieved 20 June 2014.

- ↑ Govaerts, R. "Washingtonia filifera (Rafarin) H.Wendl. ex de Bary, Bot. Zeitung (Berlin) 37: LXI (1879).". World Checklist of Selected Plant Families. Retrieved 21 June 2014.

- ↑ Cornett, J. W. 1986. Arthropod visitors at Washingtonia filifera (Wendl) Flowers. Pan Pacific Entomologist 62(3):224-225.

- ↑ Koerner, Claudia (2010-10-04). "Destructive exotic beetle found in Laguna Beach". Orange County Register. Santa Ana, California. Retrieved 20 June 2014.

- ↑ Nisson, N.; Hodel, D.; Hoddle, M. "Red Palm Weevil". Center for Invasive Species Research. University of California Riverside. Retrieved 20 June 2014.

- ↑ Dembilio, Ó.; Jacas, J.A.; Llácer, E. (August 2009). "Are the palms Washingtonia filifera and Chamaerops humilis suitable hosts for the red palm weevil, Rhynchophorus ferrugineus (Col. Curculionidae)?". Journal of Applied Entomology. 133 (7): 565–567. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0418.2009.01385.x.

- ↑ Cornett, James W. (2010). Desert Palm Oasis (Second ed.). Palm Springs, California: Nature Trails Press. ISBN 978-0-937794-42-5.

- ↑ Cornett, James W. (2011). Indian Uses of Desert Plants (Third ed.). Palm Springs, California: Nature Trails Press. ISBN 978-0-937794-45-6.

- ↑ Spencer, W. (1995). "Washingtonia filifera: Nevada's rejected ancient Palm.". www.xeri.com. Retrieved 21 June 2014.

- ↑ Spencer, W. (1995). "A report regarding: The Palm - Washingtonia filifera - in Moapa NV". www.xeri.com. Retrieved 21 June 2014.

- ↑ "Washingtonia filifera: Washington palm". RHS Gardening. Royal Horticultural Society. Retrieved 21 June 2014.

20. Real Palm Trees - General Palm Tree Information

Further reading

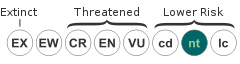

- Johnson (1998). "Washingtonia filifera". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2006. International Union for Conservation of Nature. Retrieved 11 May 2006.

- Floridata.com: Washingtonia filifera

- Cornett, J. W. 2010. Desert Palm Oasis. Nature Trails Press, Palm Springs, California.

- Interactive Distribution Map for Washingtonia filifera

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Washingtonia filifera. |

- USDA Plants Profile: Washingtonia filifera (California fan palm)

- UC Jepson Manual treatment — Washingtonia filifera

- Calflora Database: Washingtonia filifera (California fan palm)

- Washingtonia filifera in Flora of North America

- Washingtonia filifera (California fan palm) — U.C. CalPhotos Gallery